Abstract: The ongoing Ukraine crisis has irreversibly altered the global geopolitical landscape, increasing nationalist sentiments, accelerating deglobalization, and making the global geopolitical order more complicated and fragile. It has limited direct impacts on the Hong Kong economy and financial market, but its indirect implications as it reshapes the global economy, monetary policy, financial market, and geopolitics should not be overlooked. While adding to risks facing Hong Kong such as weakened efficiency in resource allocation, the Ukraine crisis has also presented it with new opportunities to emerge as one of the most important global centers for asset and wealth management.

It has been almost two months since the Ukraine crisis broke out. The black swan event has dealt huge blows to the global financial market, causing drastic fluctuations in asset prices. The ripples it has sent across the world have also reached Hong Kong.

Hong Kong has few direct economic, trade, or financial interactions with either Russia or Ukraine, and so it has suffered limited direct impacts. However, as a highly open global financial hub, it has been so integrated into the world economy and finance, and particularly exposed to shocks from tensions between China and the United States, that it could never stay immune to the blows given how the Crisis has reshaped the world economy, monetary policy, financial markets, and the geopolitical landscape. The Ukraine Crisis has brought both opportunities and challenges for the Hong Kong economy.

I. LIMITED DIRECT IMPACTS

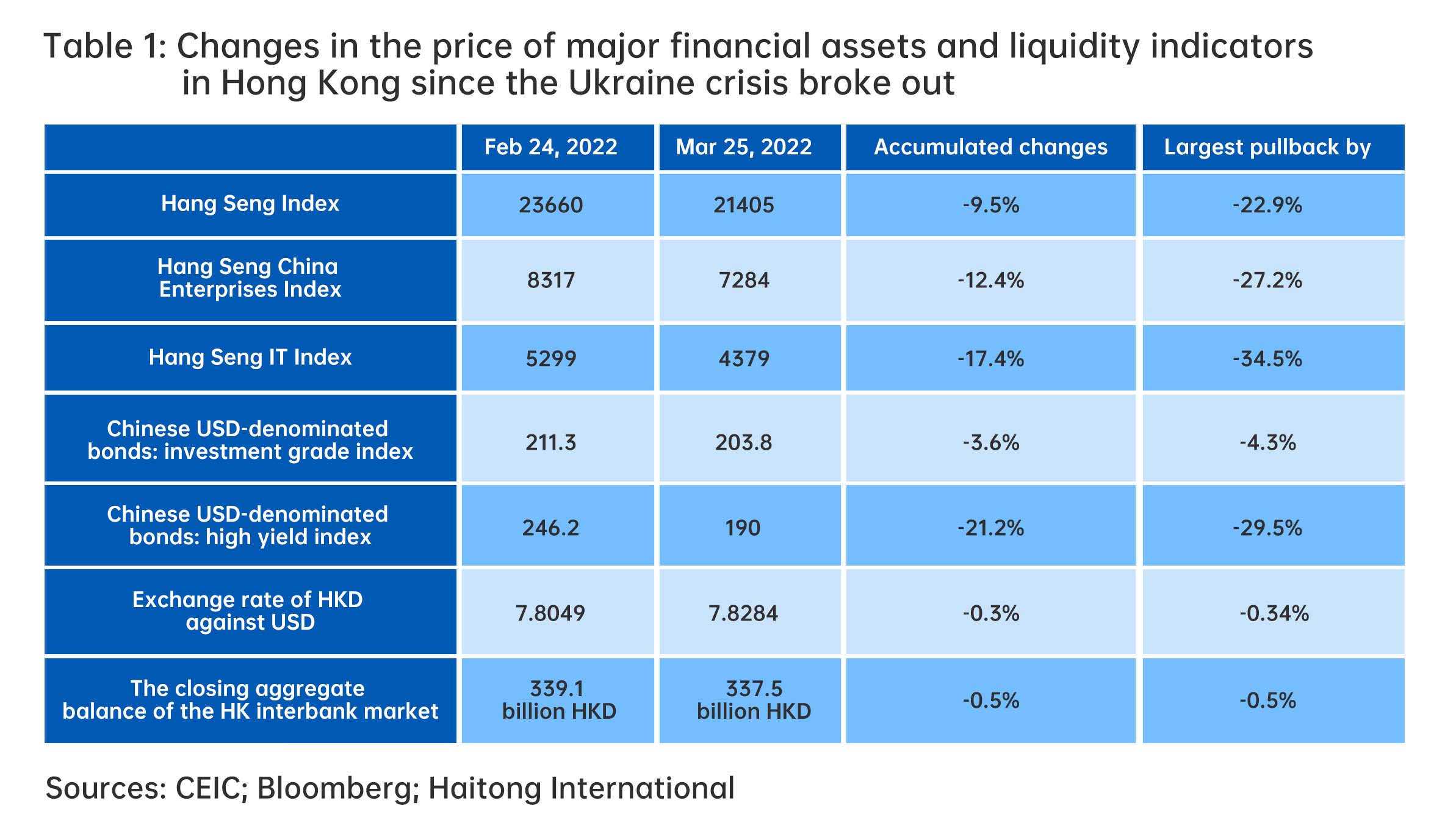

The outbreak of the Ukraine crisis has pushed up global risk aversion sentiments, causing tremendous fluctuations in the stock, bond, monetary, and foreign exchange markets of Hong Kong (Table 1). However, the total impact has been limited, and Hong Kong has not suffered any major capital outflow or liquidity crunch.

1. Money market and foreign exchange market

Since February 24 when the Ukraine crisis broke out, the Hong Kong interbank market has recorded a stable closing aggregate balance at around 337.5 billion HK dollars for most of the time, edging down by 0.5% only; the overnight Hong Kong interbank offered rate (HIBOR) reduced by 1bp to 0.02%; and its monthly HIBOR rose by 16bps to just 0.32%, far from enough to trigger a liquidity crunch.

The exchange rate of the Hong Kong dollar (HKD) decreased from 7.8045 to 7.8281 against the US dollar (USD) by a minor 0.3%. While having continued the downward trend over the past year or so, the currency has yet to reach the threshold to be deemed “weak” under the linked exchange rate regime (7.85), indicating that there has not been a significantly higher expectation for its depreciation.

These show that Hong Kong has managed to maintain the stability of its money market and foreign exchange market in general, without seeing any severe capital outflow or liquidity crunch.

2. Hong Kong stock and bond markets

The Ukraine crisis outbreak has indeed been followed by plunges in stocks and Chinese USD-denominated bonds in Hong Kong (Table 1), but the crisis is not the only culprit. Instead, there are an array of factors at play, including a weakening Chinese economy, rising defaults with Chinese USD-denominated bonds, tightened regulation by the United States on Chinese stocks listed there, and the fast spread of the Omicron variant, among others.

While hard to measure quantitatively, these factors are estimated to override the Ukraine crisis in explaining the fluctuations in the Hong Kong stock and bond markets based on capital flow statistics.

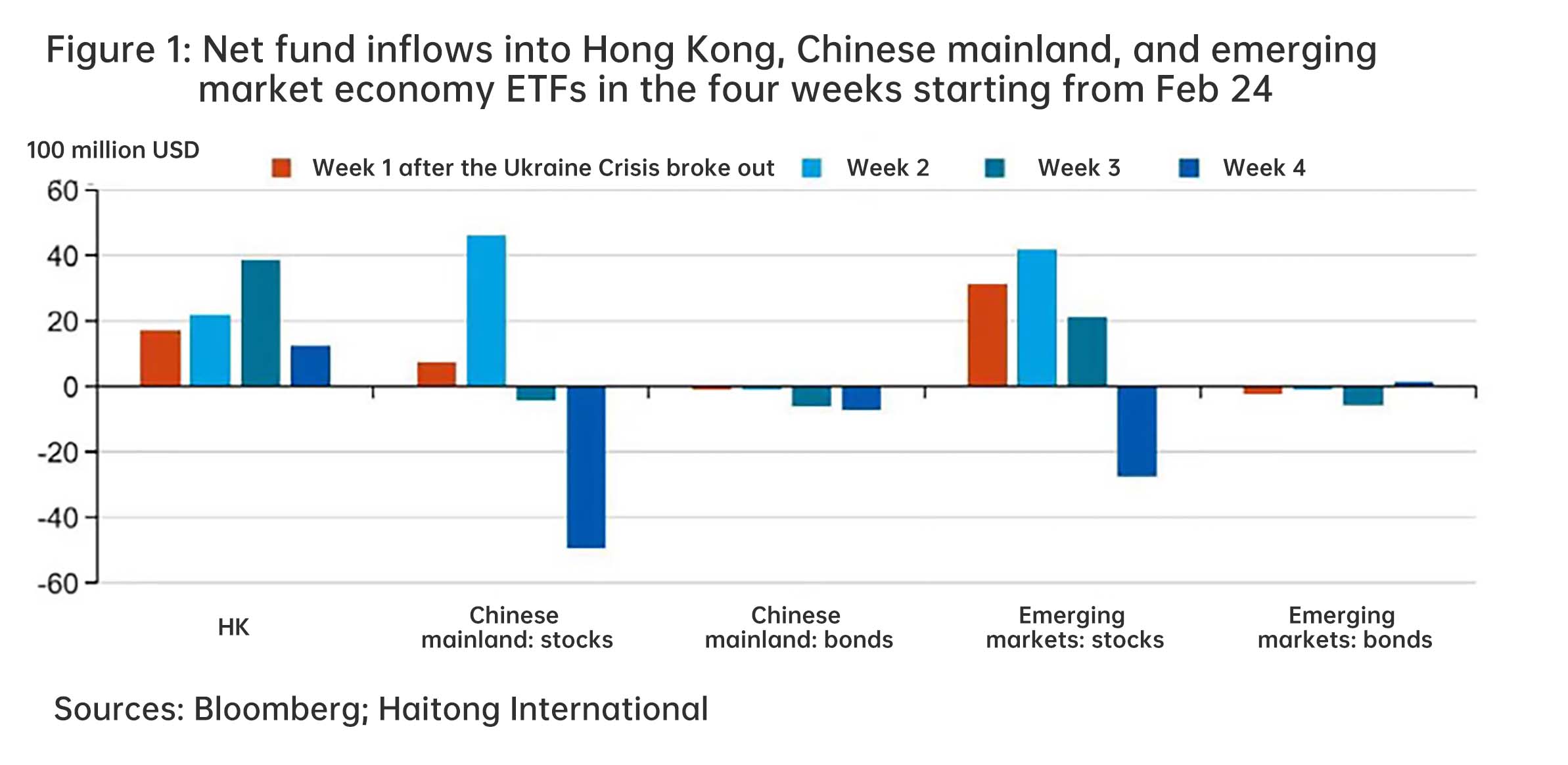

Bloomberg’s track of net capital inflow for 4 consecutive weeks via ETFs based on financial assets in Hong Kong (Figure 1) and net fund inflow from the Chinese mainland via the Shanghai- and Shenzhen-Hong Kong stock connects (mounting to 61.1 billion HKD) suggests that the Ukraine crisis has not driven capitals out of Hong Kong.

Of particular note, four weeks into the Ukraine crisis, fund inflows into ETFs in Hong Kong slumped, echoing the large-scale fund outflows from stock ETFs in both Chinese mainland and emerging market economies in the same week. Given that this happened in the fourth week, not the first or second, after the war broke out, a week that saw no significant development compared with the previous one, these outflows may not be a consequence of the Ukraine Crisis, but of internal factors in China, the Fed’s interest hike (March 16), or other factors. These statistics show that the direct impact of the Ukraine crisis on the Hong Kong market has been quite limited.

The only Russian company listed in Hong Kong is RUSAL (SEHK: 486), whose share price once plunged 55% since February 24 before rapidly picking up by over 70% as global aluminum price surged, with a monthly accumulated drop of 35%. Yet, RUSAL, around 60 billion HKD at market value, is not a constituent stock of the Hang Seng Index, accounting for less than 0.2% of the total capitalization of the Hong Kong stock market, and so its stock price fluctuations have almost no material impact on the market in general.

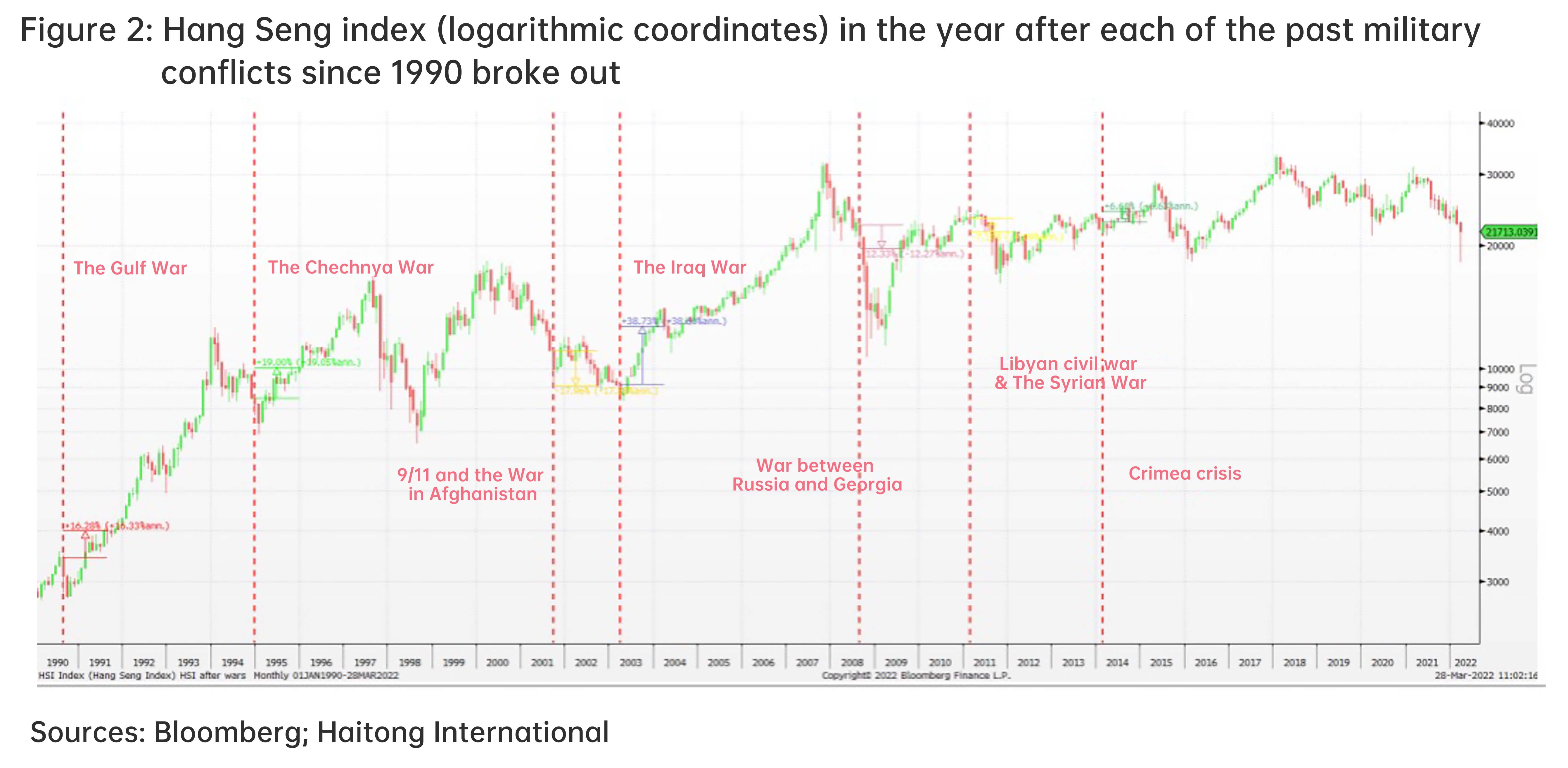

Historical data suggests that the impact of geopolitical affairs such as wars or military actions on the Hong Kong stock market has usually been transitory (Figure 2).

There has been a total of 8 military conflicts in history since 1990 that affected the Hong Kong stock market. Except for the ongoing Ukraine crisis, there were the Gulf War in 1990, the Chechnya War in 1994, 9/11 and the War in Afghanistan in 2001, the Iraq War in 2003, the war between Russia and Georgia in 2008, the Libyan civil war and Syrian War in 2011, and the Crimea crisis in 2014. For the year after each of the past 7 crises, the Hang Seng Index recorded positive returns for four times and negative returns for the rest three times, with an average annualized return of 6.2%. The military conflicts in 2008, the year of the global financial crisis, and in 2011, the year of the European debt crisis, aside, the Hong Kong stock market achieved an average annualized return of 14% for the year after the outbreak of the rest 5 crises in history. These show that the performance of the Hong Kong stock market is more a result of its own fundamentals and other global macro factors, while geopolitical events such as military conflicts only exert temporary and secondary impacts on it.

3. Energy and agricultural product supply

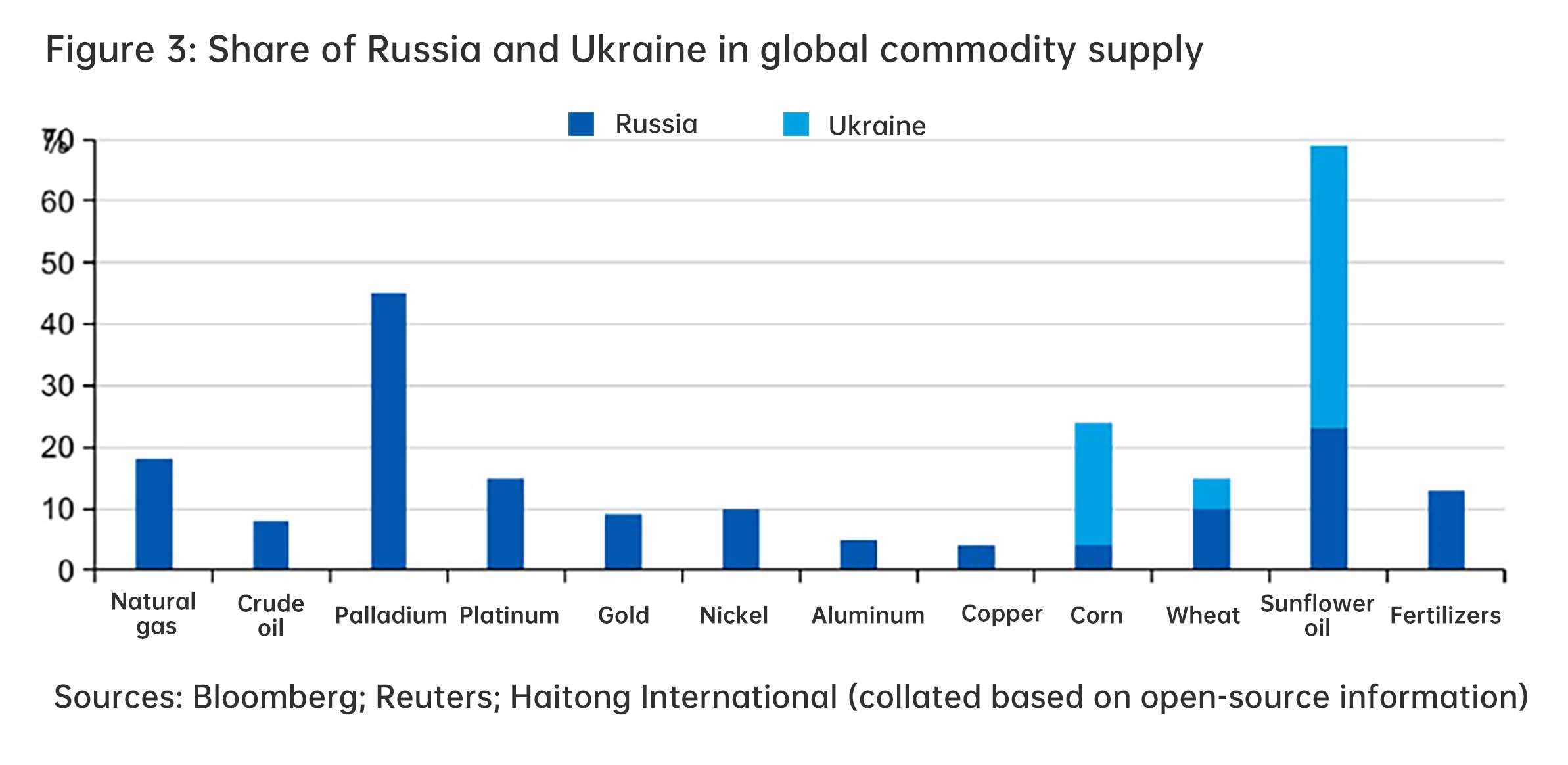

Both Russia and Ukraine are major commodity exporters (Figure 3). Thus, the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis, the Western countries’ sanctions on Russia, and Russia’s retaliation have disrupted global commodity supply, exacerbating shortages and price surges.

However, Hong Kong does not have many direct trades with either country, given its low demand for energy, industrial metals, and agricultural products. Considering this, the direct blow of the Ukraine crisis to energy and agricultural product supply in Hong Kong should be quite moderate.

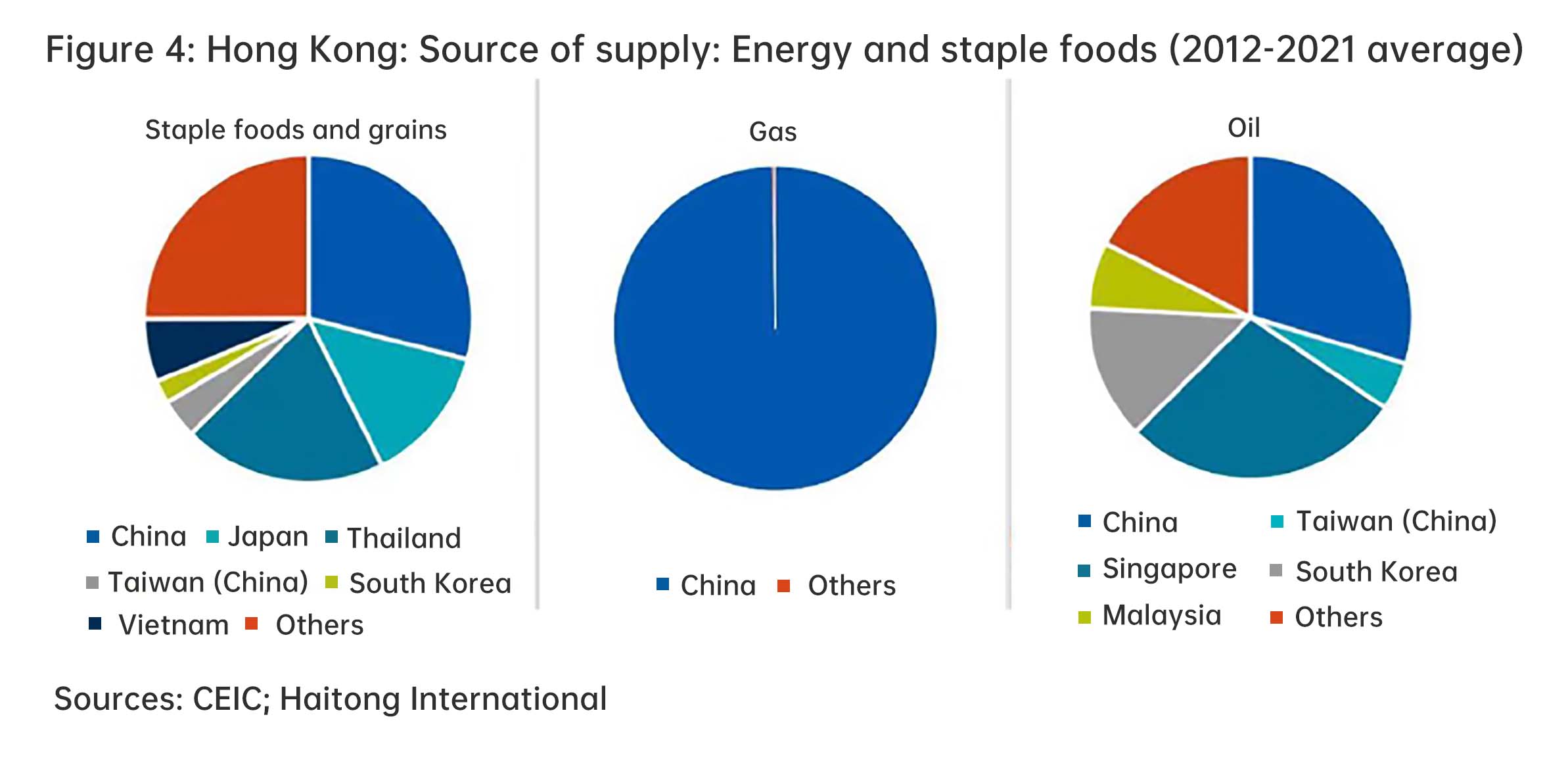

Hong Kong has few direct trade contacts with Russia, which accounts for at most 0.4% of its total imports and 1% of its total exports; the two numbers in Ukraine’s case are even lower, at 0.1% and 0.06%. Hong Kong hardly relies on either country for food or energy supply. About 75% of its imports of rice, wheat, corn, soybeans, and other major foods come from Asian countries (Figure 4), almost 100% of its gas import from Chinese mainland (which imports mainly from Southeastern Asia, the Middle East, and the U.S. while Russian supply accounted for only 5-10% in the past 3 years), and around 80% of oil products from East Asia (including refined oil from Japan and South Korea and crude oil from the U.S. and Southeast Asia) and the Middle East (transited via Singapore). Hong Kong, with a population of only 7.4 million, has limited demand for food and energy, and it can easily find alternative suppliers.

Hong Kong has few direct trade contacts with Russia, which accounts for at most 0.4% of its total imports and 1% of its total exports; the two numbers in Ukraine’s case are even lower, at 0.1% and 0.06%. Hong Kong hardly relies on either country for food or energy supply. About 75% of its imports of rice, wheat, corn, soybeans, and other major foods come from Asian countries (Figure 4), almost 100% of its gas import from Chinese mainland (which imports mainly from Southeastern Asia, the Middle East, and the U.S. while Russian supply accounted for only 5-10% in the past 3 years), and around 80% of oil products from East Asia (including refined oil from Japan and South Korea and crude oil from the U.S. and Southeast Asia) and the Middle East (transited via Singapore). Hong Kong, with a population of only 7.4 million, has limited demand for food and energy, and it can easily find alternative suppliers.

4. Inflation

While the Ukraine crisis may have kept global food and energy prices high for a prolonged period of time, its direct impact on local price in Hong Kong is limited.

In theory, energy price hike will push up transportation costs, while food price hike increases food-related inflation. However, Hong Kong is equipped with a sound public transportation system, and with most of its people commuting with public transport, it has low demand for gas and other energy products and low total commuting cost that accounts for only 6.2% in its comprehensive CPI (in contrast to 16% in the U.S.). Therefore, energy price hike has limited direct impact on the commuting costs of the Hong Kong people.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong people like to dine out, and so the proportion of “eating out and take-out orders” in the local CPI stands at 17.1%, much higher than that of “basic food” at 10.4% (in contrast to 8.2% and 6.7% in the U.S.). This indicates that food CPI in Hong Kong is to a large extent subject to changes in store rents and service prices, while the price of food such as grains has much lower direct influence on it.

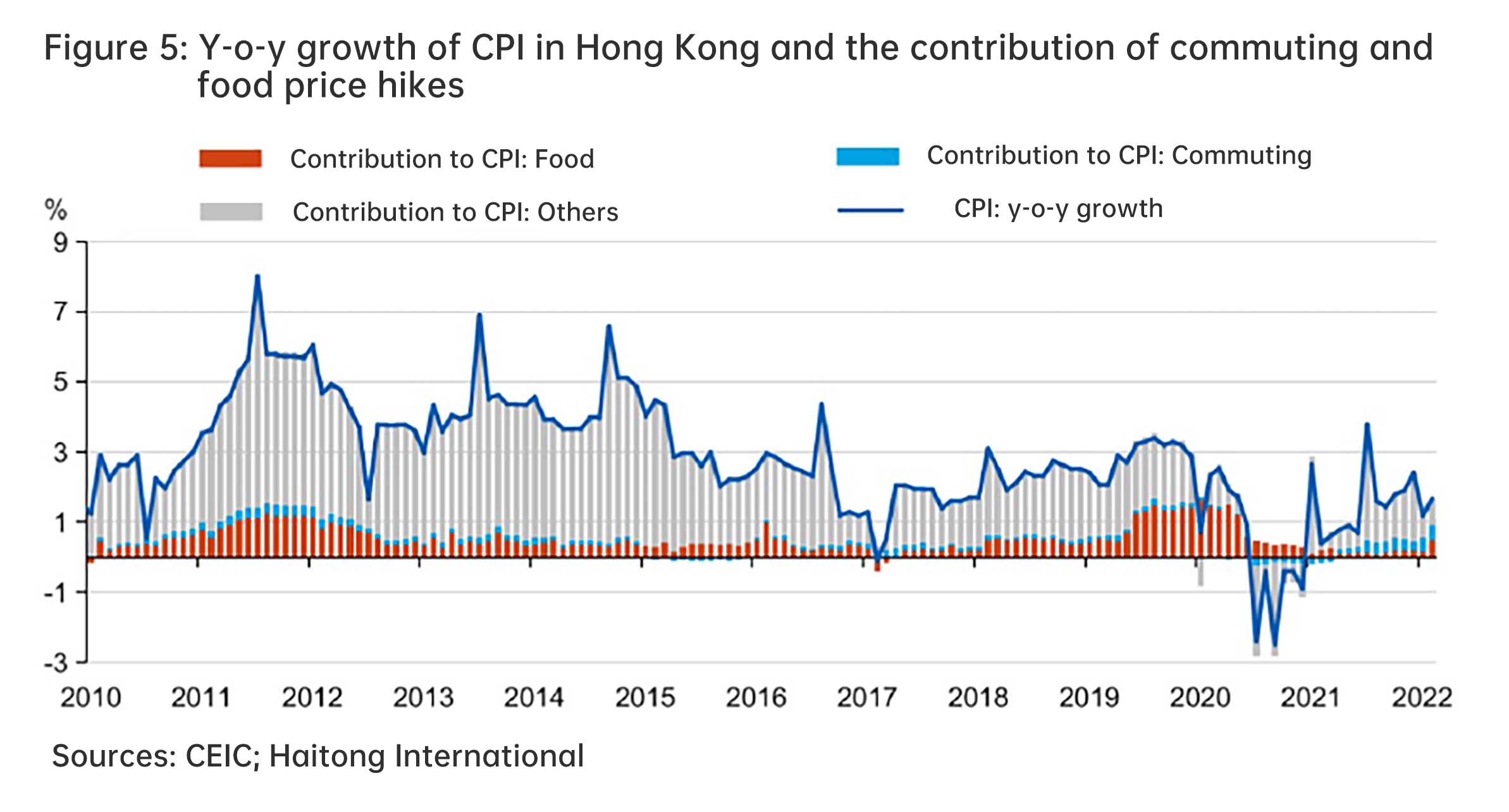

According to historical data, over the past two decades, the commuting CPI in Hong Kong is only 36% correlated to global energy price (S&P / Goldman Sachs commodity energy index), while its food CPI is only 21% correlated to global agricultural product price (food price index as measured by the U.S. Commodity Research Bureau). Over the past year, global energy and food price climbed up by 72% and 46% year-on-year (y-o-y) respectively, while only 0.9% of the rise in CPI in Hong Kong has been attributed to higher food and commuting costs (Figure 5), indicating the rather weak link between global energy and food price changes and the CPI of Hong Kong.

II. NOTABLE INDIRECT IMPACTS

Despite the limited direct impacts, the Ukraine crisis has notable indirect implications for the Hong Kong economy and financial market.

As a highly open global financial hub, the Hong Kong economy and market are extremely exposed to the impacts of factors related to global economic growth (especially that in Chinese mainland and the U.S.), inflation, central bank policies, capital flows, financial stability and geopolitics.

That’s why we must understand the Ukraine crisis’s impacts on these factors to figure out its indirect implications for the Hong Kong economy and financial market.

1. Indirect impact from faster Fed tightening

The Ukraine crisis outbreak and ensuing sanctions have disrupted global commodity supply, causing shortages and pushing up prices, further aggravating the already worrying inflation worldwide and forcing Western central banks to step up their monetary tightening moves.

This could add to risks of global liquidity crunch, capital outflow in emerging market economies, and higher financing costs, putting Hong Kong’s financial stability under threat.

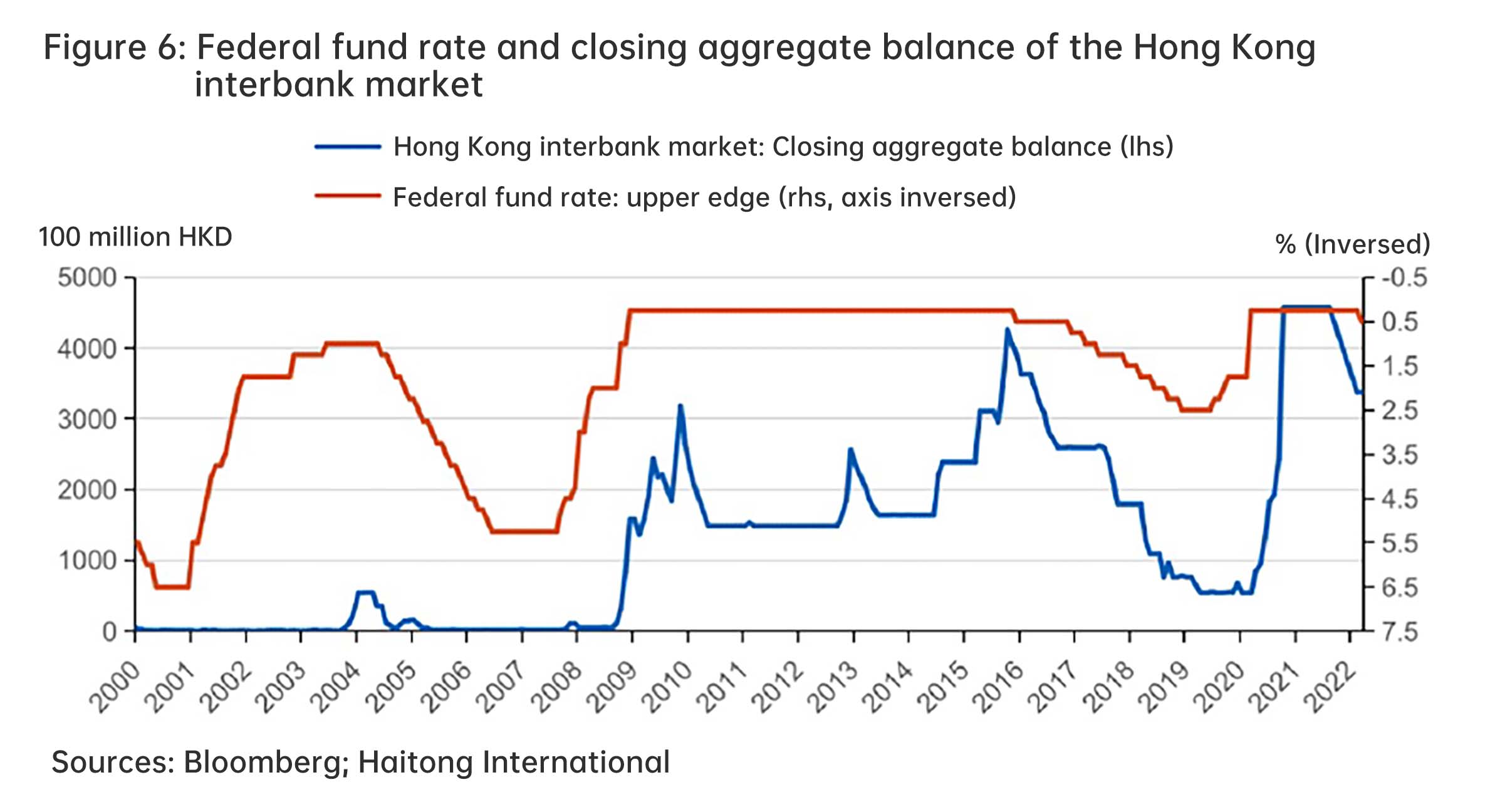

Given Hong Kong’s level of openness, its weight in global finance, and its linked exchange rate regime, its liquidity is very much affected by the Fed’s policy.

Past data reveals a strong correlation between liquidity contraction in the interbank market in Hong Kong and the Fed’s rate hikes (Figure 6). Should the Fed pick up pace with rate hikes and tightening amid the mounting uncertainties as a result of the Ukraine crisis, there could be higher-than-expected contraction of liquidity in the Hong Kong money market posing threats to the stability of the local real estate market and the robustness of the banking system.

Should the escalating conflicts further push up inflation and force bigger tightening moves by the Fed, it could increase the Treasury bond rate to a higher-than-expected level, elevating the benchmark rate of the bond market and making financing more expensive for bond issuers. At the same time, supply chain disruptions and business operating difficulties as a result of the Ukraine crisis, coupled with higher financing costs and heavier debt burdens because of faster Fed tightening, could increase businesses’ credit spreads; it may also widen the sovereign credit spreads for emerging market economies by igniting risk aversion sentiments and exacerbating their capital outflows. All of these uncertainties could add to the financing costs of bond issuers in Hong Kong or financing difficulties facing them, causing even more trouble for the already disturbed Chinese USD-denominated bond market.

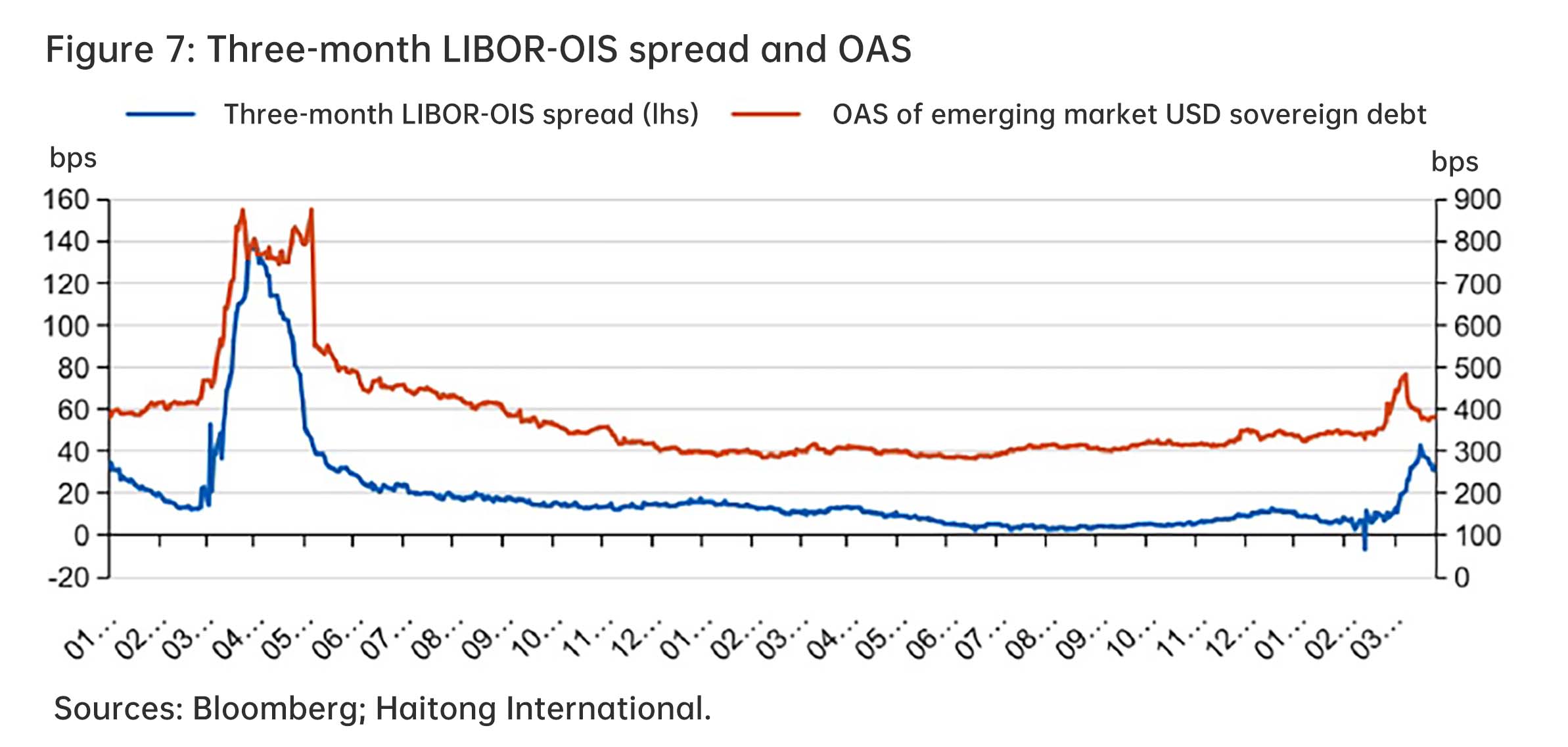

Following the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis on February 24, the US 10-year Treasury yield increased by 51 bps to 2.488 on March 25; the Barclays US High Yield Corporate Bond Spread increased by 48 bps; the LIBOR-OIS, which represents the difference between offshore and onshore USD funding, increased by 32 bps; and the OAS of emerging markets' USD sovereign debt increased by 70 bps (see Figure 7). Even though both US high yield spreads and EM bond OAS have lately declined sharply, we can't rule out the chance that the development in the Ukraine crisis would lead to a further widening of spreads, or perhaps a recurrence of the March 2020 spread spike.

In light of this, Chinese-issued US dollar bonds should be on the lookout for deterioration in dollar liquidity or a rise in credit spread.

In fact, due to a pandemic-depressed offshore US dollar liquidity in Hong Kong (see Figure 7), Kungfu bond issuance nearly stalled from March to May 2020 but revived once dollar liquidity returned to normal. Before the Ukraine crisis, the China Bond Investment Grade Chinese Offshore USD Bond Index had down 8% from its high last year, while the High Yield Bond Index had dropped 55.5% due to frequent bond defaults.

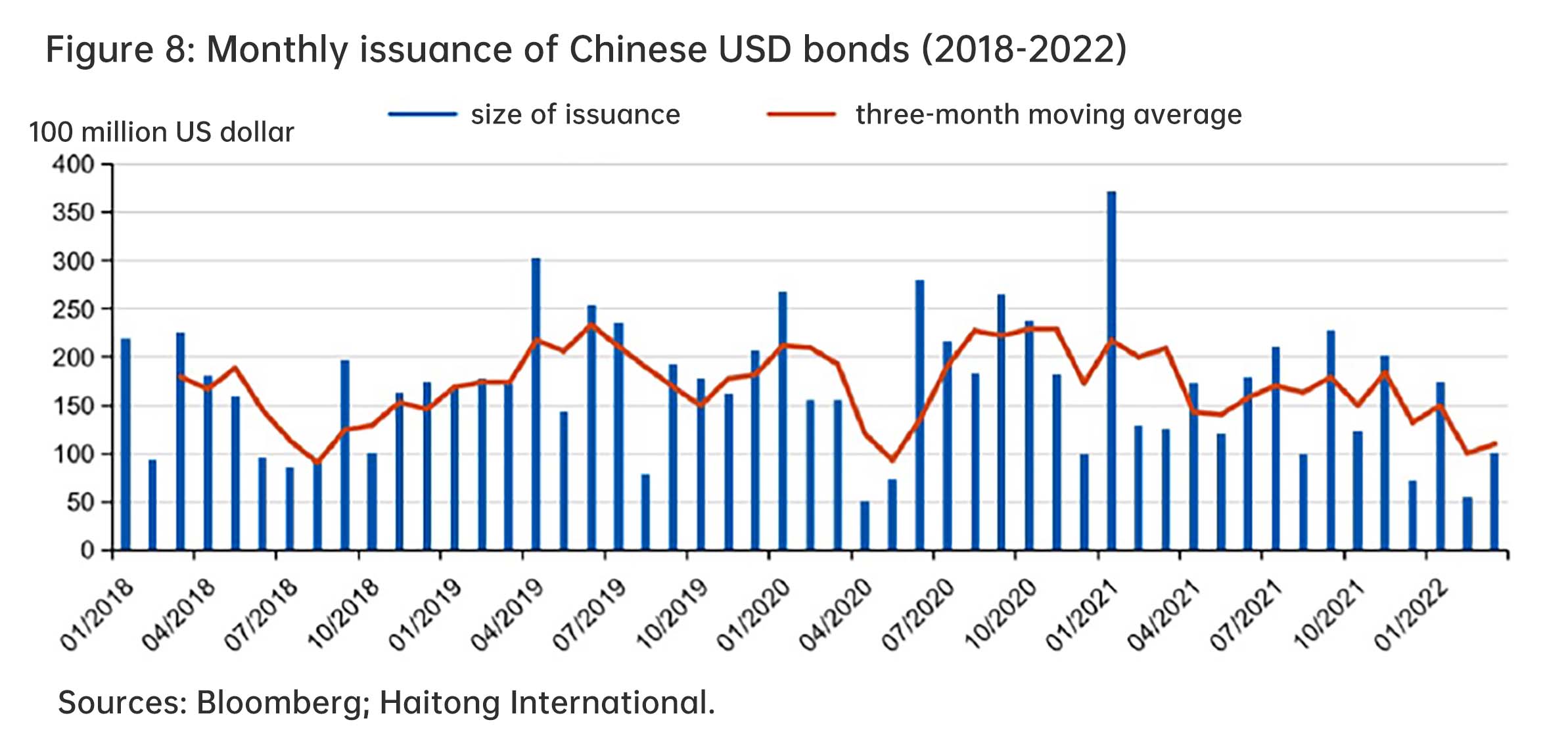

In the next two years, repayments on Chinese dollar-denominated debt will reach a peak. Data show that more than US$130 billion in Chinese USD bonds will be due between March and December 2022, with another US$124 billion due in 2023, but bond issuance has been declining since the 1H2021, with only US$38.1 billion issued in the first three months of this year, down 39% from the same period last year (see Figure 8), indicating obvious financing difficulties. If issuers are unable to roll over their debt, default risks will rise.

As a result, if the Ukraine crisis escalates or the Fed accelerates its tightening, the March-May 2020 bond issuance freeze could recur, further complicating the Chinese USD bond market.

However, the impact of the Fed's rate hike and liquidity contraction on Hong Kong stocks is not always bad.

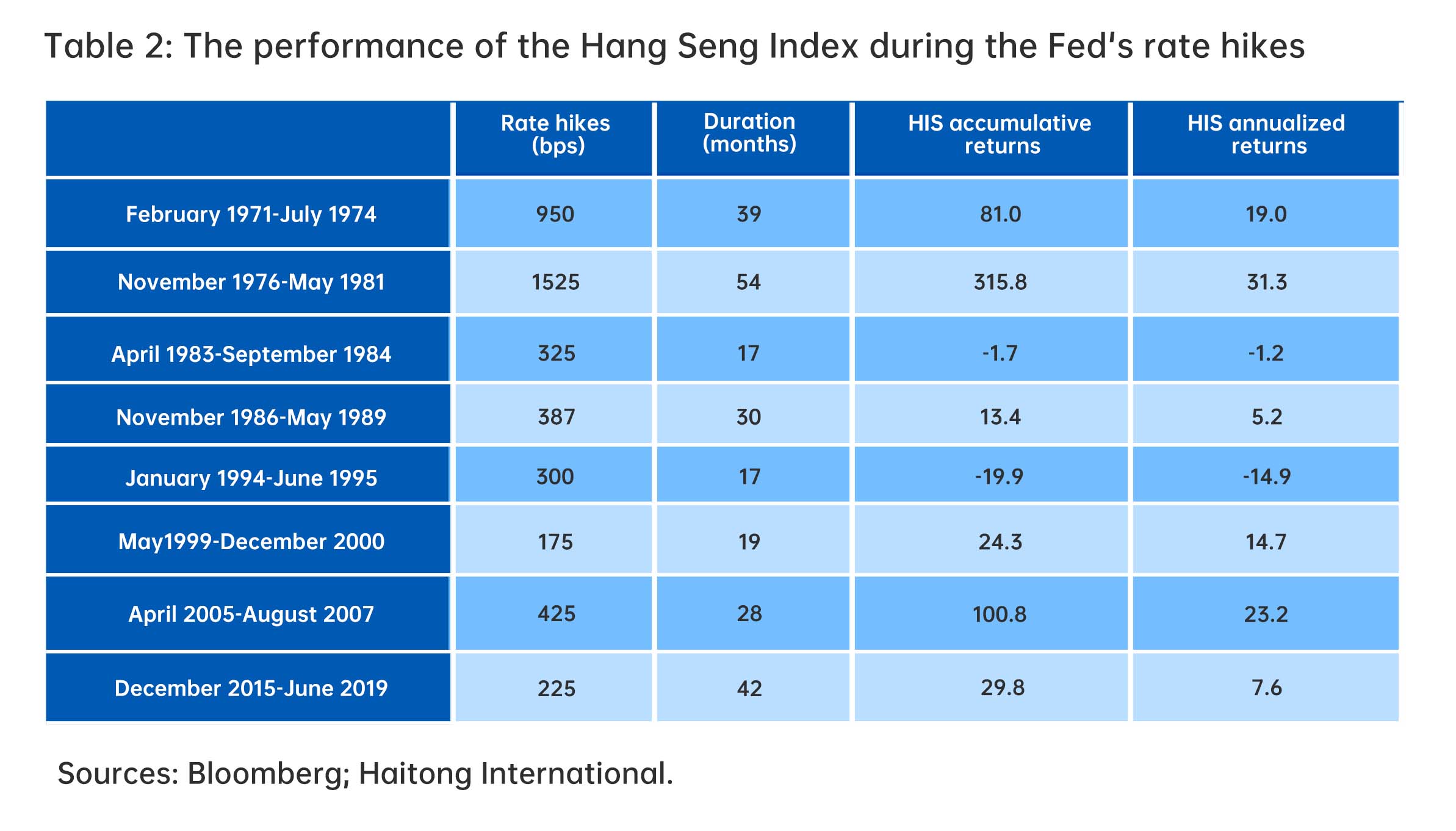

Since 1970, the U.S. has gone through eight hikes and Hong Kong stocks have recorded positive returns in six of them, with an average annualized return of 10.6% (see Table 2). During the three hikes under inflationary pressures in the 1970s and 1980s, Hong Kong stocks generated a fairly high average annualized return of 16.4%. Thus, at least from historical data, Hong Kong stocks shouldn’t be afraid of inflation-based hikes and liquidity tightening.

As a result, the future of Hong Kong equities will be more reliant on company earnings. Given that China's Mainland accounts for around half of Hong Kong's market capitalization, the Ukraine crisis is more likely to affect Hong Kong stocks indirectly through its impact on the Chinese economy (rather than the Fed's monetary policy).

2. Indirect impacts on the stability of financial institutions

The Ukraine crisis could indirectly impact Hong Kong’s financial system through the stability of the financial institutions in the U.S. and EU.

The asset price volatility brought about by the Ukraine crisis, the severe sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU and the U.S. (e.g. trade embargoes, asset freezes, and disconnection of payment systems), and Russia's countermeasures, will inevitably affect some US and EU companies and financial institutions (e.g. hedge funds, investment banks, commercial banks, and even insurance companies); some institutions of a certain size and systemic importance may be hit hard (like what happened to the Long-Term Capital Management, or LTCM, in the 1998 Russian financial crisis). Together with the accounting system, it may take longer for these traumas to be uncovered.

If the confrontation between Russia and Ukraine worsens, these wounds are likely to grow more severe and concentrated. With a cluster of EU and US financial branches and a close link to their financial markets, Hong Kong's financial institutions and markets could be affected by that time.

3. Indirect impacts from the changing geopolitical landscape

Since the crisis between Russia and Ukraine erupted, western countries have reacted forcefully by putting harsh sanctions on Russia, and Russia has responded in kind. Although it is hard to anticipate how long the fight will go or how it will finish, it will undoubtedly have a long-term and far-reaching impact on the global political, economic, diplomatic, and military environment.

Regardless of our intentions, international geopolitical relations have irreversibly changed; nationalist tendencies in all countries will intensify; "counter-globalization" will accelerate; the international arms race will most likely resume; the global geopolitical situation will become more complex and more fragile.

China has always pursued an independent and peaceful foreign policy, as well as an opening-up development strategy, striving to promote a diversified, multilateral, and globalized international economic and political landscape, but the Ukraine crisis could throw China's development path into disarray.

In the short term, the military conflict may have an impact on China's international trade and domestic economic activities through the disrupted global supply chains, adding to the challenges faced by a Chinese economy already under pressure from domestic demand contraction, supply shocks, and weakening expectations.

In the medium to long term, the crisis may affect China's opening-up process by reshaping the international industrial landscape, altering geopolitical relations, and hastening "deglobalization” adding uncertainties to China’s promotion of major strategies like the Belt and Road Initiatives, RMB internationalization, and dual circulation.

Hong Kong, as the gateway to China's global economic opening and a financial center heavily reliant on the mainland economy and market, will bear the brunt of these risks and challenges.

Faced with these unprecedented changes, western and Chinese multinational corporations and financial institutions will re-examine the potential impact of changing international relations on their global business layout, asset security, supply chain arrangements, and payment and clearing system selection, and will take measures such as asset restructuring, supply chain reorganization and industry repositioning to mitigate the relevant geopolitical risks as much as possible.

The crisis, as well as the sanctions and counter-sanctions that have followed, have served as a wake-up call for global institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) to reassess the safety of their investments in various regions/countries, currencies, asset categories, custodians, and even counterparties, and reallocate their assets globally. These actions will have a significant influence on global economies and financial markets.

These changes bring both challenges and opportunities to Hong Kong.

On the one hand, strengthening nationalism and deglobalization are bound to have an impact on the free flow and optimal allocation of capital around the world, potentially weakening the investment and financing functions of a highly open international financial center like Hong Kong in terms of global capital allocation efficiency.

On the other hand, when MCNs, financial institutions, institutional investors, and HNMIs reshape their business layout, supply chain, and asset allocation in the coming years, it will open up opportunities for Hong Kong's investment banks, AMCs, WMCs, and other types of financial institutions in M&A, investment, financing, asset and wealth management, and custody.

Hong Kong offers the institutional advantage of combining asset protection with operational ease that is unmatched by other international financial hubs for institutions and individuals with a focus on asset security, particularly in China. As a result, Hong Kong stands out as one of the world's most important asset and wealth management centers in the changing global geopolitical scene.

The article was first published on CF40’s WeChat blog on March 30, 2022 in Chinese. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the authors themselves. The views expressed herein are the authors’ own and do not represent those of CF40.