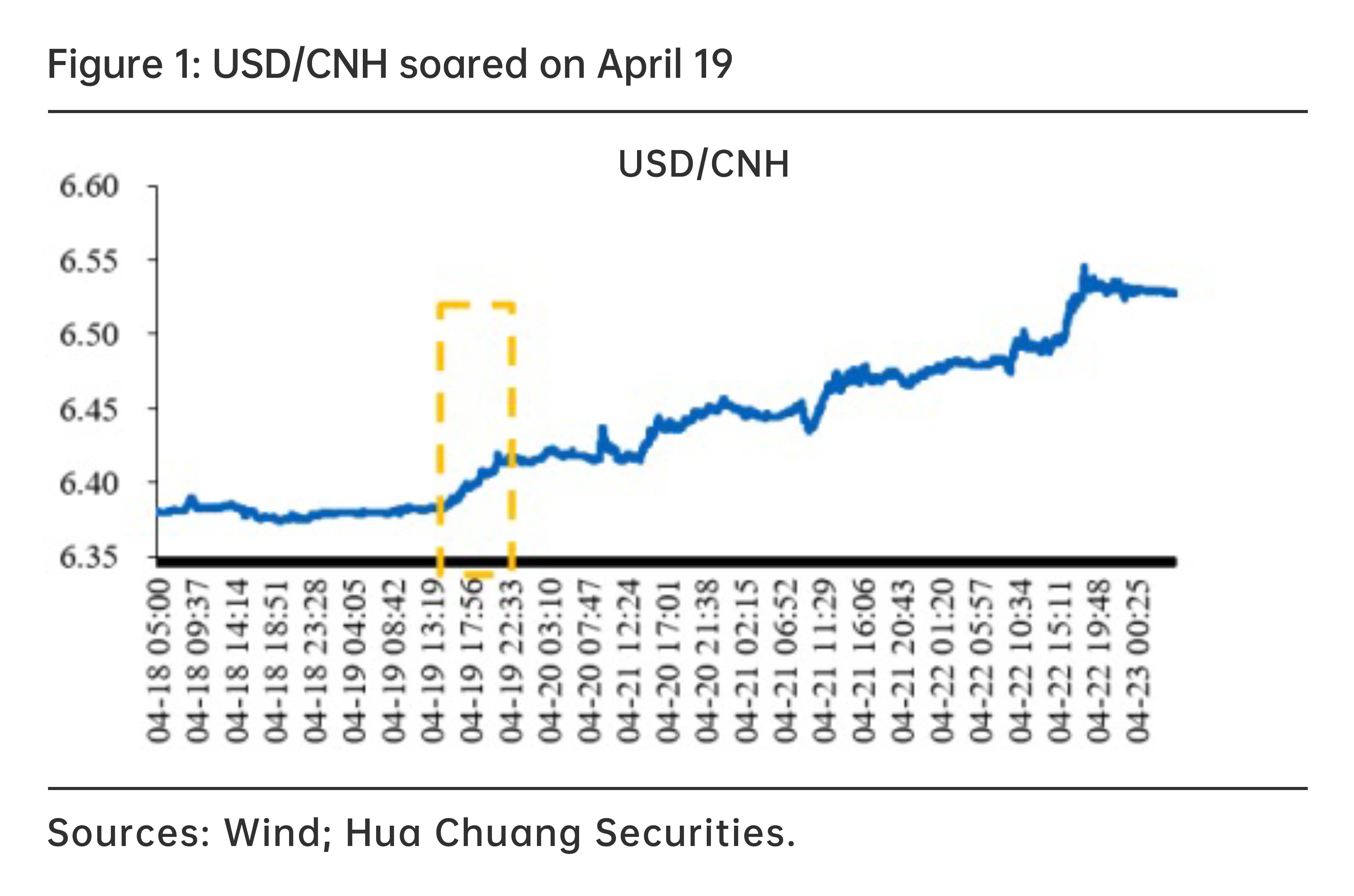

Abstract: The Chinese currency significantly weakened last week: USD/CNY dropped from 6.369 to 6.5015, down by 2.1%, from April 19 to 22; at the same period, offshore USD/CNH tumbled from 6.3788 to 6.5274. The RMB vitality went beyond the key psychological level and triggered great concern. This article will provide answers to some common questions in the market:

Ⅰ. Why did the RMB yuan weaken?

CNY played catch-up, along with other trading factors.

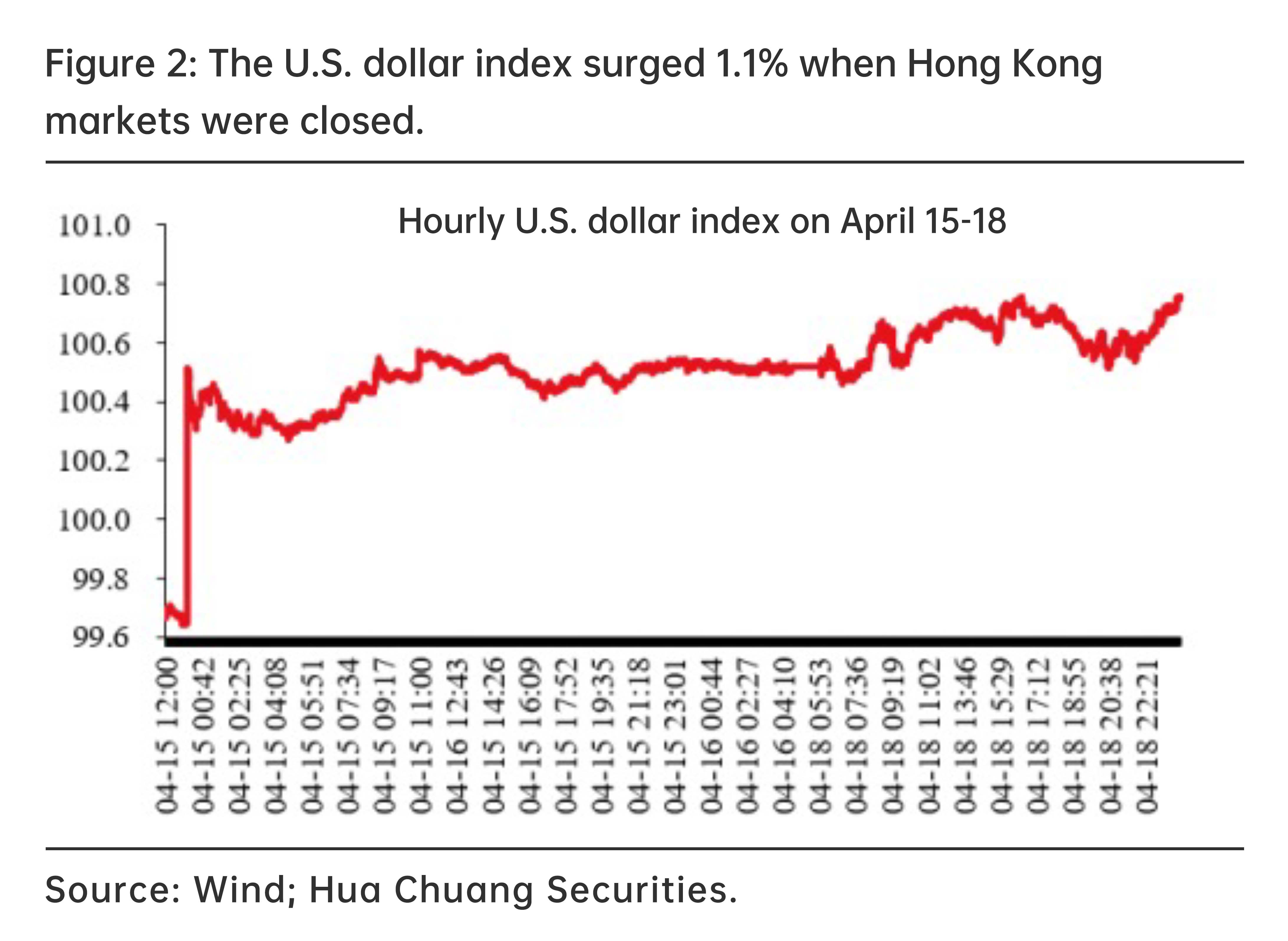

At around 3 pm on April 19 Beijing time, CNH price played catch-up to plummet from 6.38 to 6.39 in one hour, as the U.S. dollar index rose1.1% when Hong Kong markets were closed from April 15 to18 for the Easter holiday. The catch-up also dragged down the spot CNY.

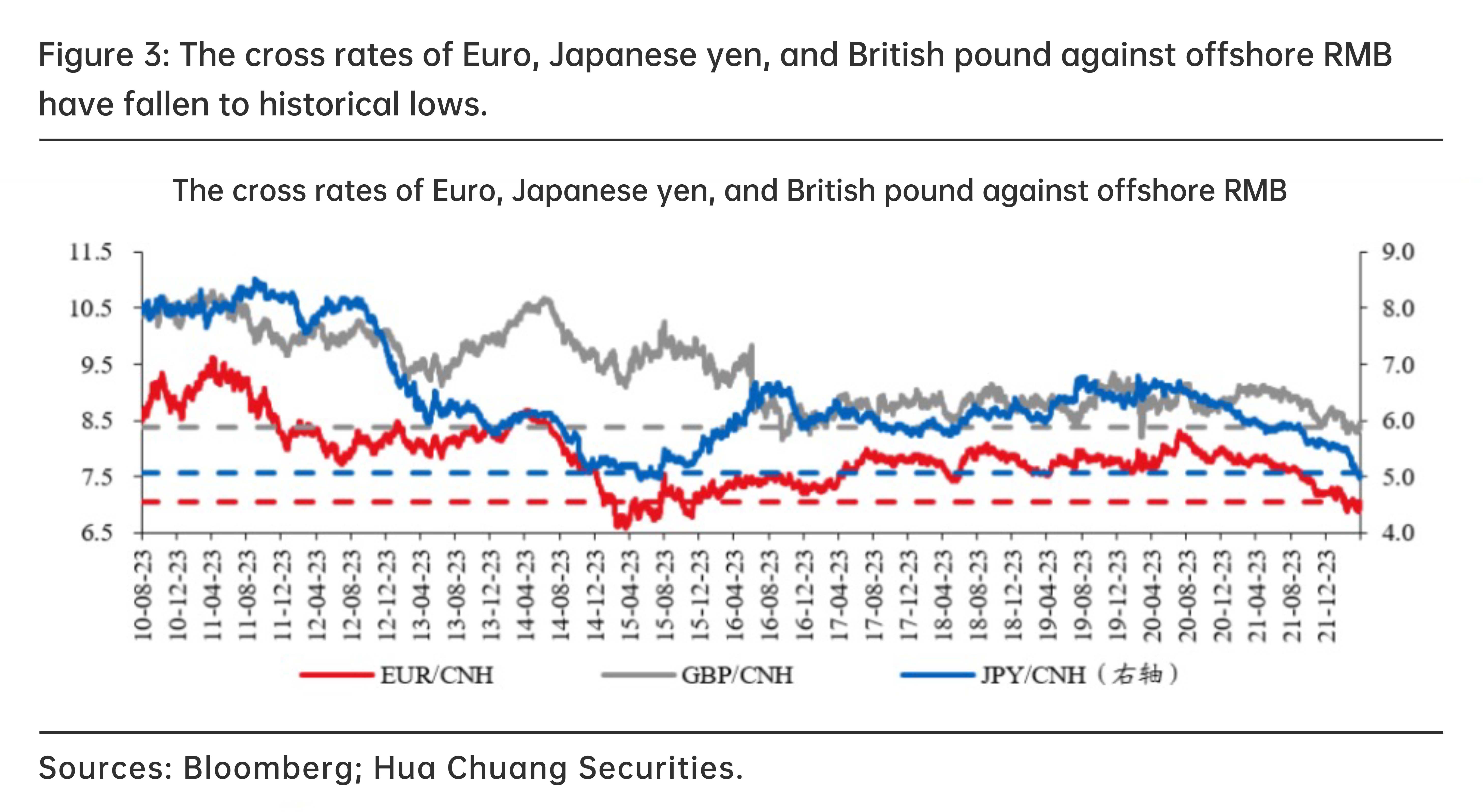

The drop in the RMB exchange rate is also coupled with disruptions caused by some trading factors. The cross rates of the Euro, Japanese yen, and British pound against offshore RMB have fallen to historical lows, driving up the demand for the former currencies while putting depreciation pressure on RMB.

II. Did the central bank guide this round of depreciation?

No, it did not.

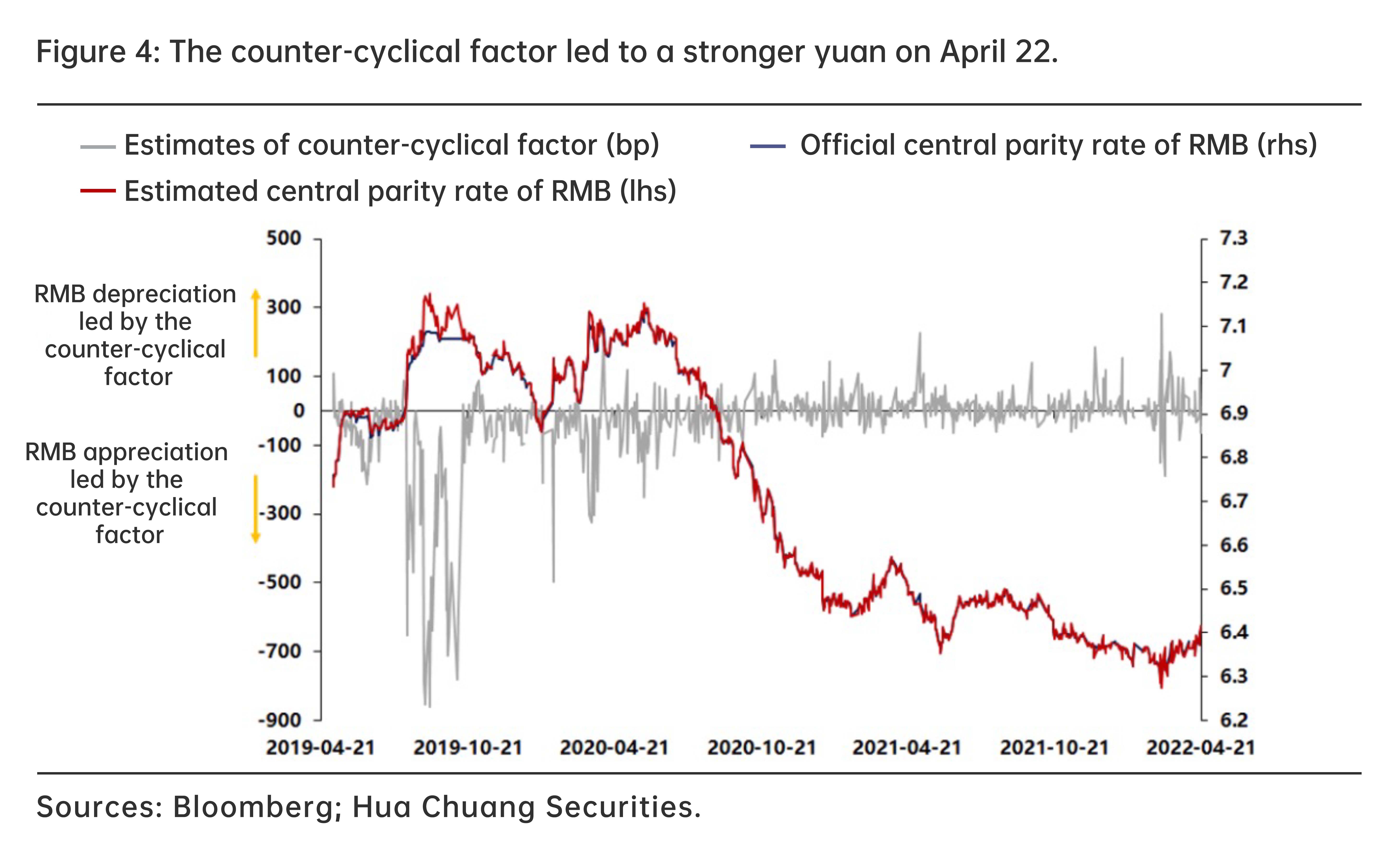

Based on the pricing model of macro exchange rate created by Hua Chuang Securities, so far this year, the period of increased volatility of counter-cyclical factor has mainly occurred in the early stage of the Russia-Ukraine conflict; due to market sentiment and volatility of the Russian ruble exchange rate, the central parity rate of RMB against USD also fluctuated to some extent and the central bank thus made short-term two-way adjustments through counter-cyclical factor. Since this round of deprecation starting on April 19, the counter-cyclical factor has not significantly led to a weaker RMB, but instead, the factor reached -123 bps on April 22 (leading to the direction of appreciation), indicating that policy tends to curb rapid depreciation and therefore this round of depreciation is not guided by the central bank.

III. Why the current drop in offshore RMB can spill over into the onshore RMB market?

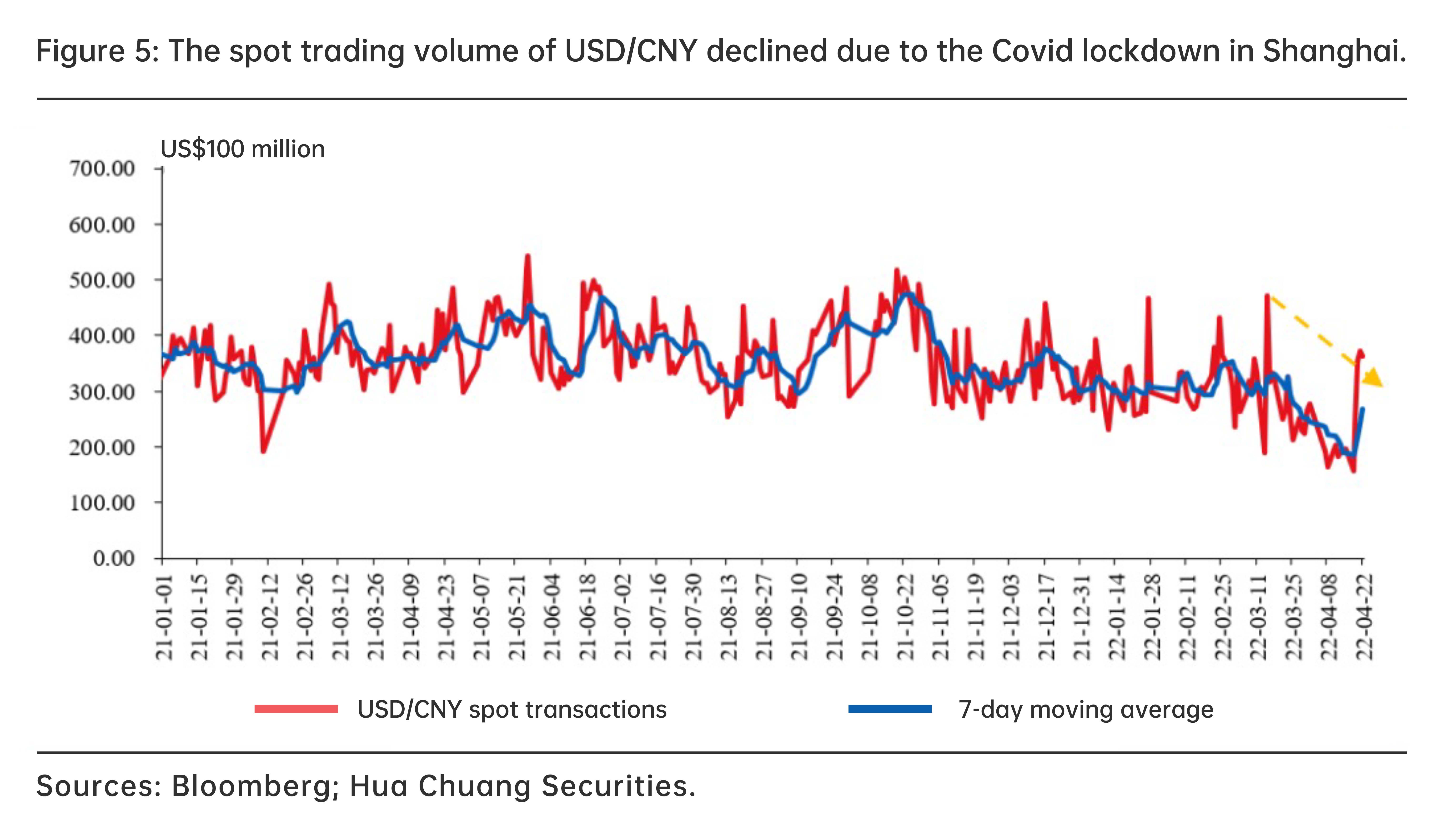

Shanghai’s Covid-19 outbreak had an impact on the trading volume of onshore spot RMB.

Due to the impact of the Covid lockdown in Shanghai, the trading volume of USD/onshore spot RMB has declined, making the onshore RMB market more susceptible to volatility in the offshore market. Given Shanghai’s status as a financial center, the increasingly strict lockdown has affected the transactions of USD/onshore spot RMB. Since Shanghai implemented city-wide static management of the pandemic in late March, over-the-counter USD/RMB turnover has dropped from the normal level of 32 billion US dollars per day to around 20 billion US dollars per day. The sharp decline in onshore RMB transactions has made the onshore spot rate more vulnerable to the volatility of the offshore exchange rate.

IV. Has a new cycle of RMB devaluation started?

No solid evidence.

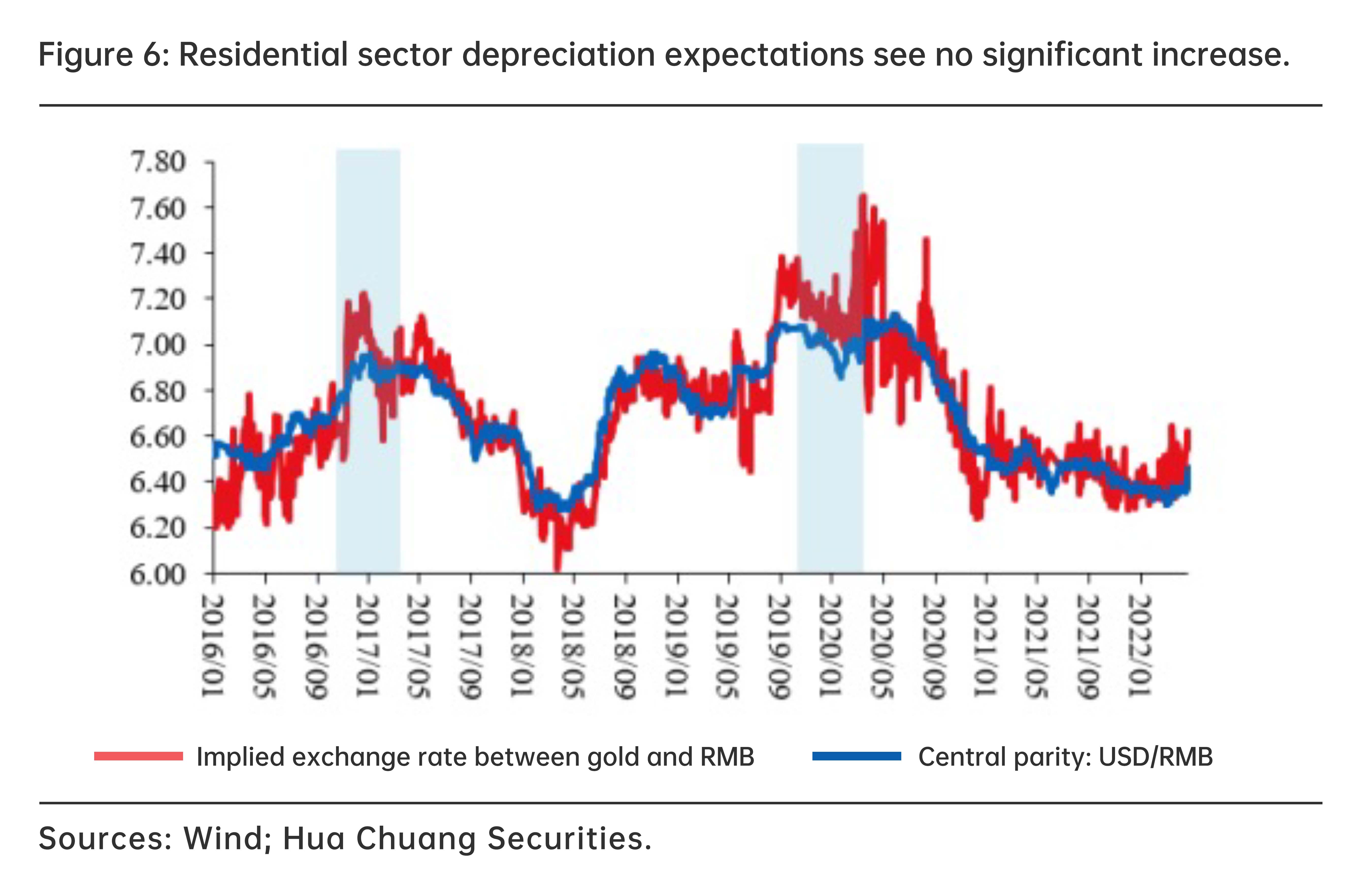

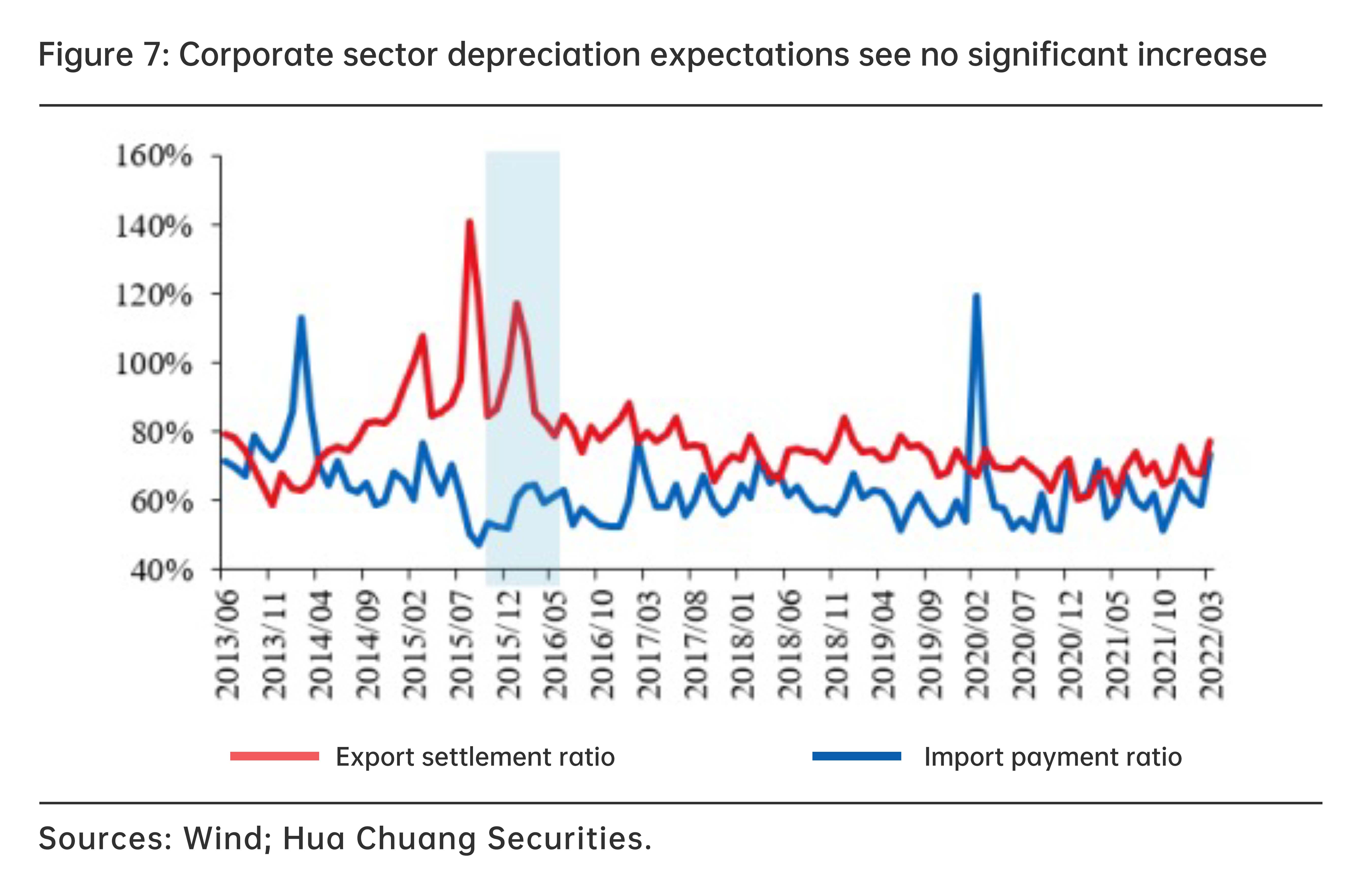

This round of RMB depreciation is mainly driven by intensive plunges offshore. Currently, depreciation only lasted for 4 trading days (April 19-22), and the depreciation range and pace were not dramatic. Meanwhile, the recent depreciation expectations of the residential and corporate sectors have seen no signs of rising, and market expectations are still relatively stable. Therefore, there is no solid evidence to prove that we are now having an exchange rate risk, but it is essential to pay close attention to the pace of depreciation in the coming days.

V. Two conditions for devaluation: weak exports and weak PMI

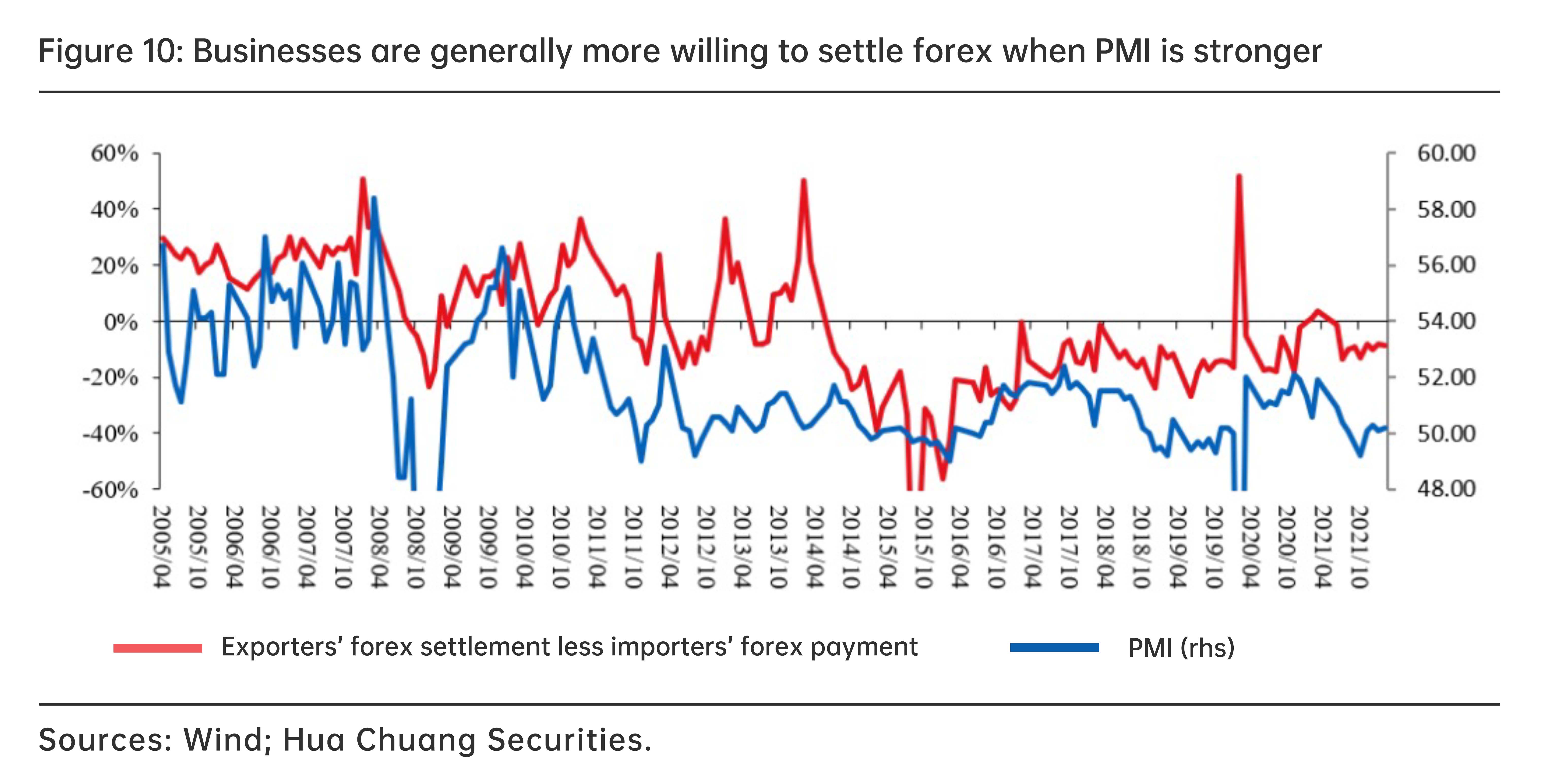

We believe that RMB devaluation needs to meet two conditions - weak exports and weak PMI. Once the PMI rises, accelerated foreign exchange settlement will provide support for the RMB exchange rate.

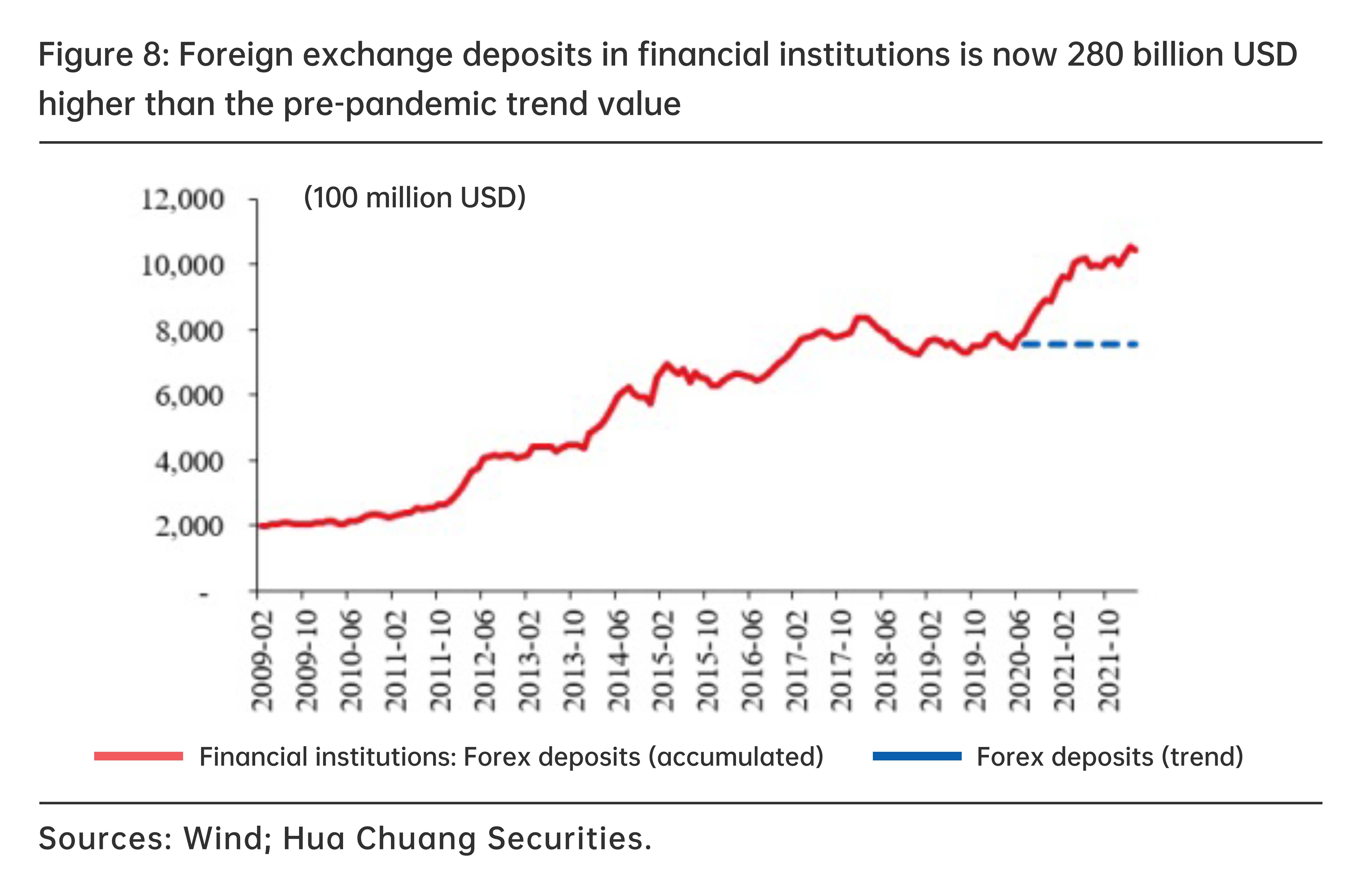

First, the unsettled foreign exchange of 300 billion US dollars will provide strength to support RMB.

The scale of foreign exchange deposits in financial institutions can measure the foreign exchange funds of the residential sector, which are not settled with banks, but are directly deposited in the foreign exchange deposit accounts of banks in the form of foreign exchange. The scale of foreign exchange deposits in financial institutions remained at the level of about 750 billion US dollars before the pandemic, and quickly jumped to more than 1 trillion US dollars after the pandemic, that is, the additional unsettled foreign exchange funds increased by about 280 billion US dollars.

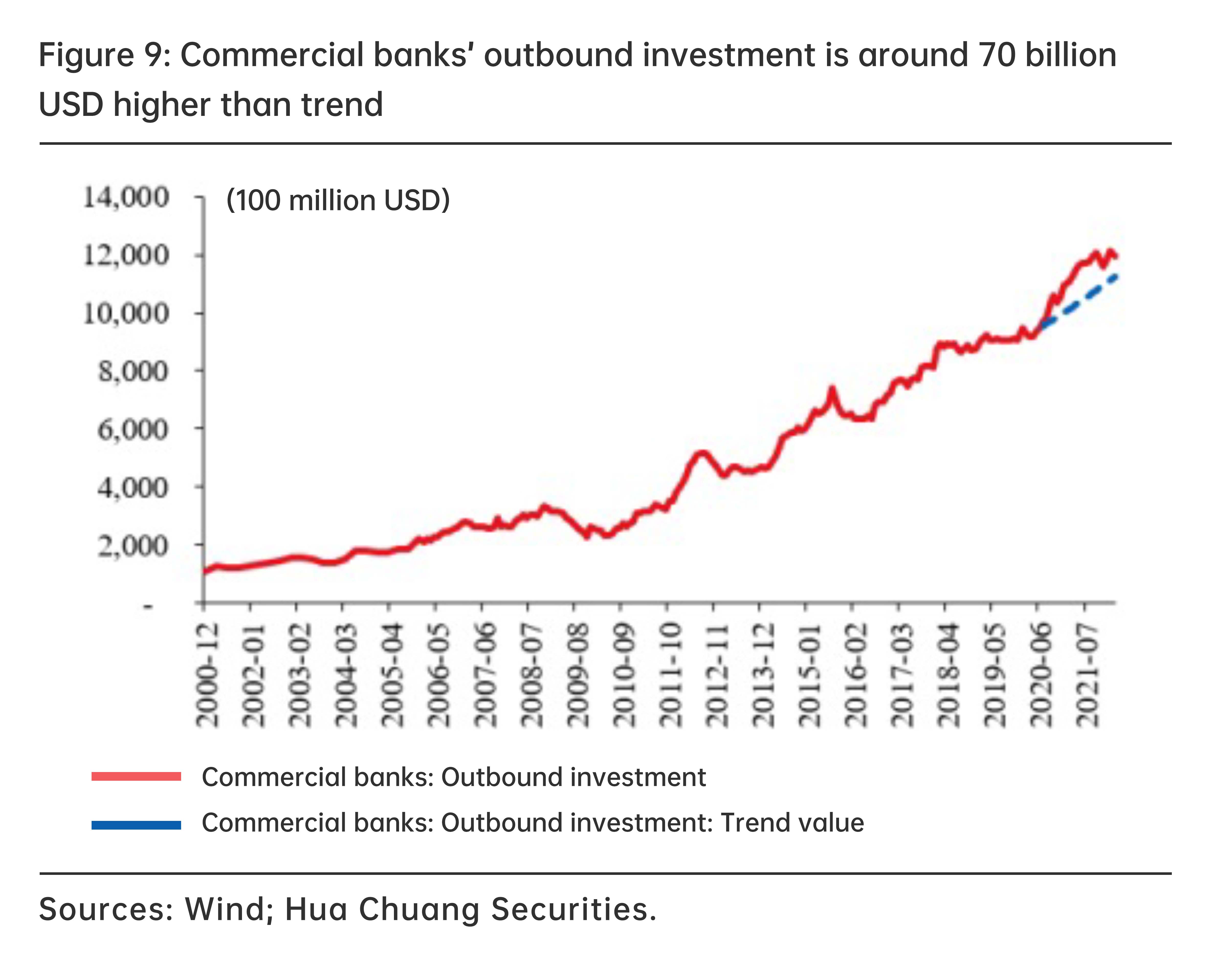

The scale of commercial banks’ outbound investment is a measure of foreign exchange funds after households’ settlement with commercial banks, which directly invest the funds abroad rather than settling them with the central bank. It also shows the scale of commercial banks’ unsettled exchange. Before the pandemic, this number grew at over 0.7% on a monthly basis on average. At this rate, it is estimated that the trend value of accumulated unsettled exchange has now been exceeded by the actual amount by around 70 billion USD.

The above two combined produce around 300 billion USD of accumulated unsettled exchange as of March, 2022.

In addition, business willingness for exchange settlement is related to the number of orders, and so their decision (exporters’ forex settlement less importers’ forex payment) basically corresponds to PMI movement which in essence represents domestic demand, reflecting the effects of policies for stabilizing growth. To this end, we envision three scenarios:

Scenario 1: High exports + higher PMI→RMB appreciates

Scenario 2: Low exports + higher PMI→RMB stabilizes

Scenario 3: Low exports + lower PMI→RMB depreciates

This shows that whether RMB depreciates or not is fundamentally determined by the level of domestic demand, or in other words, the PMI’s trend. Amid the pandemic’s blow, in March, China recorded a PMI of lower than 50 again. With this in mind, a weaker RMB is no surprise. However, given the accumulated unsettled exchange of almost 300 billion USD, while PMI moves up, the blow from any possible fall in export could be cushioned by accelerated exchange settlement, and that way the RMB could be stabilized.

This article is excerpted from the 16th weekly economic observation published by Hua Chuang Securities. The views expressed herewith are the authors’ own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the authors.