Abstract: With a fast ageing population, China needs to give bigger roles to its financial sector in support of old-age care. This article proposes policy suggestions at three fronts: (1) On pension management, China should implement a differentiated tax incentive system to boost market-based allocation of pension fund assets and expand the scope of pension fund investment for more diversified returns; (2) On financial services for the elderly, China should develop lifecycle funds, reverse housing mortgage loans/insurances, and pension trusts; and (3) On the old-age care industry, China should step up support for PPPs for old-age care, and stimulate the development of REITs to help balance needs for short-term profit and old-age care industry’s prolonged payback period.

As the second generation of baby boomers in China gets old, the country is entering a decade of severe ageing, where those aged 65 and over make up over 15% of the total population. However, the structure of China’s pension system remains unbalanced. Institutional arrangements and pension product design in support of old-age care need to be more oriented toward the wealth management demand of the elderly, in order to enable related financial innovations. Pensions, elderly-oriented financial services and the entire old-age care industry enjoy immense possibilities for growth. Meanwhile, the enlarging pool of pensions and related emerging financial products will also serve as a new source of long-term funds nourishing the Chinese capital market.

I. FASTER POPULATION AGEING: MOUNTING OLD-AGE CARE PRESSURE

China’s 7th national census suggests a notable acceleration in its population ageing, behind which is a “demographic transition” process as a result of the three waves of baby booms in the country’s history since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. The first boom dates back to 1952-1958, with around 20 million newborns annually who will near the end of their lives in around 5 years; the second boom in 1962-1972 witnessed the number of newborns reaching a historic peak, with almost 260 million newborns who will gradually retire starting in 2022; and the third boom was in 1986-1991, during which around 25 million people were born each year who will soon age over 35-40 years old and pass their best child-bearing period.

People aged 65 and above accounted for 13.5% of the total population in China in 2020, 5.44 percentage points up from 2010. As baby boomers born during 1962-1972 become old, China is entering a decade of severe ageing. At the same time, a declining fertility rate and surging dependency ratio are also adding to society’s pressure with old-age care. With fast economic development since the reform and opening-up in 1978, the total fertility rate of China has slid from 2.6 in 1980 to 1.3 in 2020, placing mounting strains on its social old-age care system. The United Nations (UN) estimates that during 2020-2055 China’s dependency ratio will rise by 31 percentage points to 51%.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic’s blow in 2020, a gap between revenue and expenditure has emerged for the first time in almost 20 years on the account of basic pension scheme for urban employees, amounting to 692.5 billion that year. And the pension gap could continue to widen in the long run. According to predictions by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), a gap will appear in the basic pension scheme for urban employees in 2028, with the total gap during 2028-2050 estimated at around 100 trillion yuan. Discounted at 4%, pensions in China need to stand at somewhere around 40 trillion yuan in 2028.

In addition, with slower economic growth and cooled market expectations for further house price hikes under tightened regulation, there will be a shift in how Chinese people view old-age care. Real estate has always been a critical part of Chinese people’s asset portfolio: in 2019, asset allocation by urban households was dominated by non-financial assets, and real estate took up 60% of total assets. China’s per-capita GDP exceeded 10,000 USD in 2019, but the overwhelming proportion of real estate as a type of fixed asset means that houses are squeezing out other financial assets which could make an affluent life for the elderly, and such overreliance could also make them more vulnerable to house price fluctuations. Thus, the traditional concept of “supporting one’s old-age life with a house” may no longer cater to a fast-ageing population’s needs. While respecting the traditional view of a decent old-age life, China should give bigger play to its financial sector in supporting old-age care.

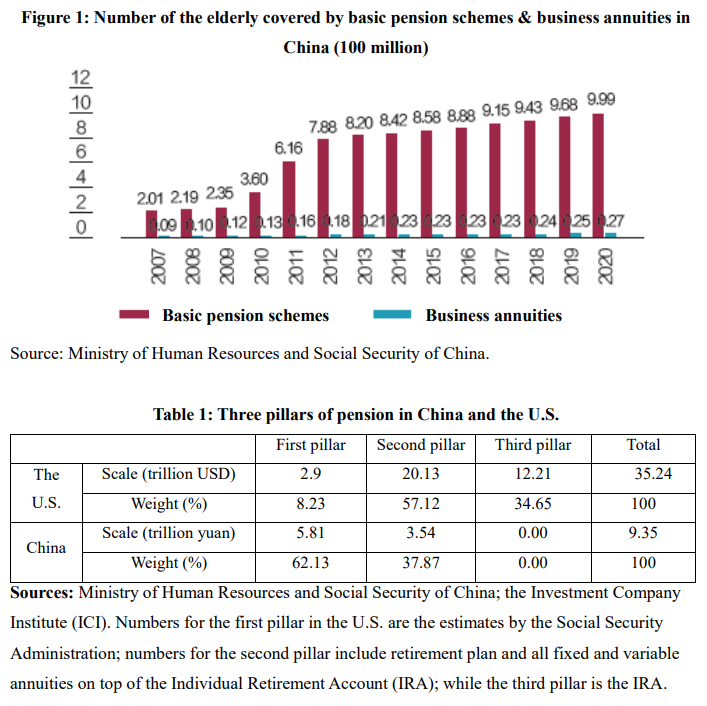

II. PENSIONS: GREATER FOCUS ON PENSION ASSET MANAGEMENT

The pension system in China is unbalanced in terms of the weight of the three pillars. In 2020, China recorded a total of 9.35 trillion yuan of pensions, in which the first pillar accounted for 62% while the second, 38%. The third pillar was relatively new in China and thus smaller in scale and lower in penetration. That is too unbalanced relative to the case in developed economies. For example, the second pillar dominates the Unites States’ pension system, accounting for nearly 60% in 2020; while the third pillar, individual commercial old-age insurance, also took up almost 30%. More importantly, not many pension funds are invested in capital markets in China. The inefficient allocation or low return of these long-term funds would stem efforts to improve the pension system.

1. Give play to a differentiated tax incentive system to boost market-based allocation of pension assets

China’s pension system is unbalanced out of many reasons, including objective and institutional bottlenecks like the late introduction of occupational annuities, business annuities and individual commercial old-age insurance, the lack of public awareness, the relatively weak profitability of small- and medium-sized enterprises and their reluctance to pay business annuities. But at the same time, the low efficiency in the capital market-based allocation of pension assets is partly owed to a lack of incentives such as tax incentives.

Some of the developed economies have given tax credits to pension accounts. Drawing on their experience, imposing “differentiated taxes on capital gains” or improving the second and the third pillar could promote the allocation of pension assets on the capital market. The U.S. collect taxes on funds with various maturities at different rates: short-term funds mature within a year were taxed at 20%, while longer-term funds with a maturity of over a year were taxed at 15%. Meanwhile, employees covered by the second pillar of the employer pension plan, the 401 (K), could enjoy tax exemptions and credits on certain charges and investment returns, while the Individual Retirement Account (IRA) was also provided with tax credits during investment (or only minimum individual income tax had to be paid). Japan now taxes capital gains at 20%, but its third pillar, the Nippon Individual Saving Account (NISA), is given exemptions on investment income in the first 5 years. Such “dual benefits” from both compound investment returns and tax credits have driven fast growth in the scale of NISA accounts at 25% annually, reaching a total of around 23 trillion Japanese yen in 2020.

Absent capital gain taxes, some of the businesses and households in China would rather invest in real estate or stocks with fast returns, instead of commercial old-age insurance with a much longer return period which won’t be used until retirement. China could consider taxing capital gains while managing funds with various maturities on a classified basis, imposing different levels of capital gain taxes. Charging higher capital gain taxes on speculative, short-term funds could increase speculation costs, thus curbing excessive fund flows and ironing market fluctuations. China could also give tax credits or exemptions to long-term funds like pension funds while reducing the individual income tax on pensions as appropriate and increasing deductibles for the third pillar. Global experience shows that such a “differentiated tax rate system” would significantly boost the second and the third pillar.

2. Expand the scope of pension investment for more diversified returns

Unlike developed economies like the U.S. and Japan, China has imposed many regulatory restrictions on the scope and proportion of investment by pension funds. It puts a cap of 30% on the proportion of investment in stocks, equity funds, hybrid funds and stock-type pension products in the total net assets of basic pension scheme funds. Similarly, business annuities’ total investment in these types of equity assets shall not exceed 40% of their net entrusted assets, while any investment in a single stock-type pension product shall not exceed 10% of their net entrusted assets.

In contrast, pensions in the United States such as IRA can invest in a wide range of financial assets, including stocks, bonds, insurance, mutual funds, bank deposits and others without any restriction on proportions. Almost half of the IRA assets have been invested in mutual funds since 1995. In Japan, NISA holders also enjoy much freedom in choosing the types of assets to invest in, including stocks, funds and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Over 57% of the money under the system went to funds in 2020.

With all of the three pillars, Chinese regulators now seem to focus on preventing losses in investors’ original capital. Going forward, while ensuring stable investment returns from social security funds, regulators could adjust their mindsets and consider expanding the scope of pension investment and implementing differentiated regulations, which would make pension asset management more efficient. Specifically, business annuities and individual pension insurances could enjoy a wider scope of investable assets by including funds, bonds and bank wealth management products, or implementing a white list of investable products or institutions and setting a certain proportion for investments in equity products; the minimum proportion of investment in equity products in total basic pension scheme funds could also be lifted as appropriate.

III. FINANCIAL SERVICES FOR THE ELDERLY: FINANCIAL INNOVATION HELP MEET THE ELDERLY’S DIVERSIFIED WEALTH MANAGEMENT DEMAND

Financial institutions of various kinds in China, including banks, funds, insurances and trusts, are engaged in old-age financial services, but the range of products remains limited. As of the end of 2020, China had a total of 598 pension products (526 publicly offered and 72 privately offered), including publicly offered funds, insurance products and bank wealth management products that were all old-age-oriented, and most of them were invested in stocks, fixed-income securities and currencies. Wealth management products targeting the elderly generally remain infant in terms of their quantity or functions, falling short of the increasing diversified demand.

1. Lifecycle funds: Explicitly tailored to old-age wealth management need

Many of the lifecycle pension products are not substantially different from other wealth management products in terms of lifecycle, maturity, investment direction, and purchase & redemption rules. They seem not specially tailored to the elderly and their investment needs. As of November 30, 2021, among the 237 publicly offered funds oriented toward the elderly, 233 were hybrid, among which 27.9% were target-date funds, 39.1% were bond-dominated hybrid funds, 20.2% were stock-dominated hybrid funds, and 12.9% were balanced hybrid funds. Among the funds, 40.08% had a minimum holding period of 3 years and above; 31.22%, 1-2 years, and the longest holding period were 5 years. Lifecycle funds are still in the preliminary stage in China. Publicly offered pension funds on average were founded 1.46 years ago, the earliest dating back to 4.18 years ago.

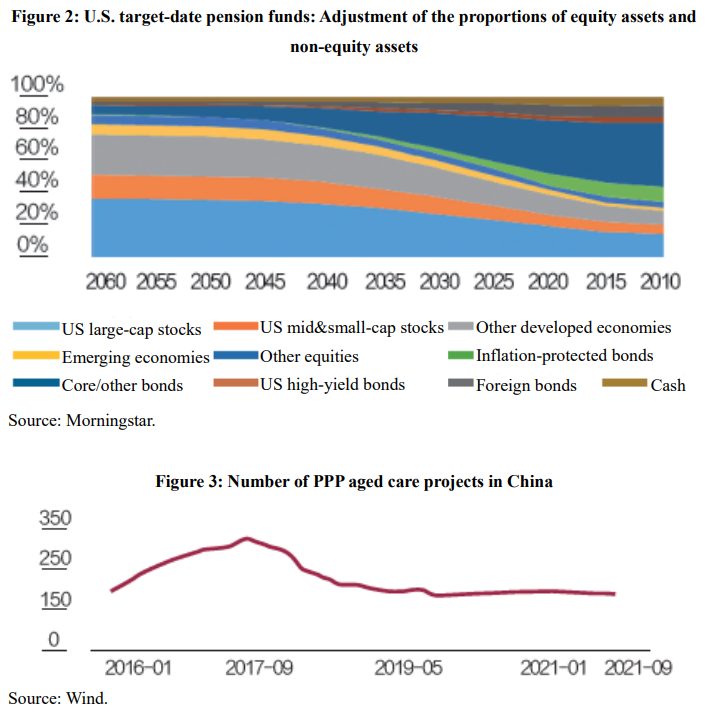

International experience shows that target-date funds tend to be more explicitly tailored to meet the elderly’s demand. The best choice with a long lifecycle, this type of fund product has the core logic of adjusting strategic asset allocation at different dates to monitor risk exposure and cater to the change in risk preference as people age. Target-date funds were first introduced in the U.S. in the 1990s. As of March 31, 2021, the U.S. recorded a total of 1.7 trillion USD of target-date funds, 85% of which were held by the country’s pension system. Target-date funds feature a glide path, with the relative weight of investment in equity assets and non-equity assets adjusted based on the risk preference and wealth creation demand/ability of investors at different ages. Typically, as the target dates get closer, the funds gradually reduce risk exposure by decreasing the proportion of equity assets relative to non-equity assets.

PTFs aimed at building “old-age wealth” should also be tailored to the unique features of the Chinese market while drawing on global experience. The Chinese equity market is more volatile than those in other countries, and this could affect target-date fund managers in their estimates of stock returns based on which they determine the weights to be given to different types of assets. In addition, in the U.S., derivatives and other various types of assets are investable for PTFs, while the scope of investable assets for Chinese PTFs is narrower. Generally speaking, as the population fast ages, PTFs in China need institutional arrangements and products that are more tailored to the wealth management demand of the elderly to boost related financial innovation.

2. Reverse housing mortgage loan/insurance: “Supporting old-age care with homes” under a new concept

With reverse housing mortgage loans/insurances, houses can serve as a source of income for the elderly by producing capital income to relieve their economic burdens. During the loan period, the homeowners can still live in their own houses; but after they pass away, financial institutions would be free to dispose of with the houses’ “residual value”. Under traditional mentalities, the house is usually inherited by its owners’ offspring; but today, with demographic transition underway and the surge in house vacancy as well as the dependency ratio, this new type of loans/insurances could give play to different economic natures of houses in generating income, serving as a new model for old-age wealth management.

Reverse housing mortgage loans began popular in Japan in the 1980s, and the Japanese government played an important role in this, involving both direct and indirect financing. For direct financing, the Japanese government established special agencies, although many of the projects had restrictive requirements on applicants; for indirect financing, the government served as the intermediary and connection between banks and applicants. Under these two mechanisms, the government and financial institutions worked together in a coordinated, mutually-supporting manner, prospering the reverse housing mortgage loan business in the country.

The Chinese first turned to this idea in 2003. Many proposed reverse housing mortgage loans to be combined with life insurance. In 2014, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Wuhan conducted a 2-year pilot program with housing reverse mortgage endowment insurance; in 2016 more cities joined, and the program was extended; and in July 2018, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) declared that it would promote experience from the pilot across the country. However, the increasing awareness has yet to translate into actions: as of now only two insurance companies, Happy Life Insurance Co., Ltd and People's Insurance Company of China, run a business on reverse housing mortgage loans.

This may be owed to several factors: first, the 70-year term of house ownership means that one may no longer lawfully own his or her home before the loans expire; second, the traditional concept of passing on houses to offspring still prevail among the elderly, and so they are unwilling to use their homes as collaterals in exchange for pensions; and third, reverse housing mortgage loans involve a lot of house disposals, but financial and rating institutions have yet to build a full set of supporting mechanisms.

The overwhelming proportion of real estate in Chinese households’ asset allocation has to a certain extent squeezed other possibilities for wealth creation. Reverse housing mortgage loans and insurances could serve as a supplement and relieve the elderly’s economic pressure by using real estate as capital. To promote this new concept of investment, China needs to improve supporting facilities, laws and standards for assessing the eligibility of borrowers and houses. It could also consider combining various types of operating entities. For example, social security institutions or lending institutions authorized by the government could contribute the financial resources, banks could evaluate and dispose of houses, while insurance companies determine the eligibility of applicants, and the government promotes the idea. Such kind of mixed operation would be a highlight in financial innovations based on reverse housing mortgage loans and insurances.

3. Pension trusts: Meeting the elderly’s demand with flexible, innovative institutional arrangements

Pension trusts have emerged in recent years as important providers of financial products targeting the elderly, but they still have a series of problems like ambiguous policies, high thresholds and an incomplete range of services. Chinese households now mainly invest in two types of pension trusts: financial pension trusts and consumption pension trusts, the former focusing on wealth management, and the latter, broader elderly spending. Pension trusts are very flexible and can well meet the diversified wealth management demand of the elderly.

Financial pension trusts aim at preserving and creating wealth for the elderly. They use their investment proceeds to meet old-age care needs. China Foreign Economy and Trade Trust Co., Ltd. and Industrial Bank Co., Ltd jointly introduced the first financial pension trust in September 2015, with a threshold for original capital investment of 6 million yuan. It was structured like a family trust, with a maturity of 3 years, while its profit allocation was similar to that of annuities. Pension trusts have the rule that the primary beneficiary must be an elderly person, exhibiting its nature as a product tailored to the elderly and their old-age care demand.

In comparison, consumption pension trusts, on top of wealth allocation and inheritance, focus more on meeting specific consumption needs of beneficiaries, such as housekeeping, nursing, healthcare and mental care, and the list could extend to include social relationships and travelling as the elderly develop new types of spending demand. With the rise of the “silver economy,” China could consider reducing the threshold for establishing pension trusts, improving pension trust property registration, and stepping up policy support like tax credits to boost the market for elderly consumption.

IV. THE OLD-AGE CARE INDUSTRY: INNOVATIONS IN FINANCING MODELS BASED ON PPPS AND REITS

The old-age care industry is special, featuring huge upfront inputs, a long payback period, and uncertain profitability. It does not meet the need of many social capitals seeking quick returns.

Banks, the main debt financing providers for the industry, prefer borrowers with safe assets and good credits and lend more to heavy-asset projects. That means light-asset companies with hardly any collaterals find it hard to borrow from banks. Private equities and venture capitals that focus on financial investment require a shorter payback period than that of the aged care industry which generates minimal returns in the near term. Private equity funds in China now typically have a maturity of “3+2” years; government funds, a bit longer than that; but both find pension funds’ breakeven period of 5-10 years way too long. Listed companies with short-term performance pressure may also find pensions unattractive. They have to disclose financial data quarterly, and if they record losses for three consecutive years they would be delisted, but pensions in their early period would usually add to losses. That’s why listed companies are cautious about pension investment.

1. PPPs for old-age care need stronger government support

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), mobilizing social capital, can play a big role in relieving the financial pressure on local governments and the old-age care industry.

First, the government could provide resources, such as lands, to pension companies to reduce their operating costs. Costing a lot of upfront capital, the land is a major bottleneck stemming pension operators’ growth. Governments can help break it, by transferring land, maybe at discount, to pension companies for old-age care purposes, or by buying their shares at land development cost price. These measures can provide the needed land, reduce risks for private capital while saving fiscal resources spent on supporting businesses.

Second, the government could lead to establishing a multi-dimensional industrial evaluation system to attract private investment of various sorts. The number of pension-related PPPs peaked in 2017, after which it gradually fell back to around 170/month today, mainly because of higher thresholds and stronger regulations. These PPPs, with very long payback periods, high uncertainties and an immature payment system, have attracted only a limited amount of social capital. To address this problem, the government could lead to establishing a sound system for industrial evaluation to promote more flexible capital contributions and transparent profit sharing and improve the PPP model. This could help attract more social capital.

2. REITs help balance short-term profit and pensions’ prolonged payback period

The U.S. once securitized real estate for the elderly by introducing REITs, attracting more social capital to participate. Over half of the investors of the top 10 American communities for the elderly were REITs. REITs by design can mobilize various resources. The U.S. successfully forged a partnership among investors, developers and operators at different stages of real estate development, where developers build homes and reap profits, REITs gain rental and asset appreciation income, while the light-asset pension operators pocket administration fees and residual earnings. By separating different types of income from development, rentals, asset appreciation and property management, risks at these different stages are also isolated, and that is a perfect match for pensions with a long payback period and need for long-term, low-cost funds.

Over the past 2 decades, Chinese laws and regulations on REITs have improved. On April 30, 2020, China launched pilots for publicly-offered REITs for domestic infrastructure projects. As of the end of November 2021, China issued a total of 13 publicly-offered REITs, with supporting laws, setups and professional talents, laying a solid groundwork for further promotion of REITs for real estate targeting the elderly.

REITs help turn the fixed assets into highly liquid assets that can be traded on stock exchanges, with low threshold, stable returns and low risks. They offer valuable clues as to promoting financing for the development of real estate for elderly people.

This article was first published on TSINGHUA Financial Review in February 2022, before being reposted by CF40 on its WeChat account on February 20. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the authors themselves. The views expressed herein are the authors’ own and do not represent those of CF40.