Abstract: The rapid global spread of COVID-19 has set off worldwide financial turmoil. But even before the outbreak, many economies have already suffered sluggish economic growth, and the underlying reasons for that are the structural vulnerabilities in the capital markets. For example, the US economy and its capital market have been inherently fragile with accumulated risks. As a result, the pandemic may trigger the end of the 10-year bull market in the United States. In comparison, the fundamentals of the Chinese capital market remain relatively optimistic, with multiple investment opportunities emerging despite the crisis.

I. Global financial markets suffer turmoil amid the rapidly developing pandemic

At present, the global financial markets are in a state of turmoil, and the direct cause is the COVID-19 pandemic. Any analysis at this point faces large uncertainties and any judgement can prove to be wrong at a later time. But it is still essential to research the markets amid the pandemic to understand some underlying laws.

The research department of China International Capital Corporation studied the spread of the disease in major countries around the world. Results show that most countries, especially those in Europe and the United States, are still in the phase of rapid growth, but in China, spread of the disease has been generally controlled.

The epidemic has caused huge fluctuations in the global capital market. From the perspective of the performance of asset prices, the pandemic shock is different from any adjustment in history as the world is encountering two shocks, public health and macroeconomic shock. Combination of the two gives rise to extensive uncertainties.

In terms of public health, people are not sure how governments should prevent and control the epidemic and whether the measures taken are appropriate; on the macroeconomic side, the world is faced with a huge short-term shock. Whether the macroeconomic policy can properly play its role and the effectiveness of the policy are not clear. Combination of the two rarely seen shocks have worsened the uncertainty (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Countries around the world face two shocks: public health vs macroeconomy

Behind a considerable uncertainty, there lies danger.

At present, multiple crises may have occurred or are taking place, and in the future they may evolve into larger crises. From the perspective of crisis transmission, a public health crisis may evolve into an economic crisis, which will lead to a liquidity crisis in capital markets, and then trigger a financial crisis, and the financial crisis will in turn further aggravate the economic crisis.

We can not be sure at the moment whether the pandemic shock will evolve into an economic crisis similar to the Great Depression in the United States from 1929 to 1933, or a global financial crisis similar to that in 2008-2009, but such possibility does exist. Moreover, this possibility is still growing, and there is widespread concern about it.

In summary, the world is at a time when multiple risks are accumulating, just on the edge of outburst.

II. US Capital Markets carry underlying vulnerability

Flies do not bite seamless eggs. Although the multiple risks mentioned above can be attributed to the shock of the pandemic, there must be deep structural problems that cause the pandemic shock to evolve into global liquidity crisis.

SpeakIng of economy, the United States and major European countries had suffered continuous economic downturn despite some weak signs of recovery before the virus outbreak started.

The rapid spread of the virus then has an extensive impact on the global economy. Research institutions have adjusted growth prospects for China, the United States and the world. Vulnerability of the global economy is obvious.

Capital markets also have inherent vulnerabilities and uncertainties, mainly lying in the credit market and the equity market. The two markets also interact with each other.

The following analysis illustrates the vulnerability of the US capital market.

On the one hand, the vulnerability of the credit market has long been overlooked, and leveraged loans may be the most vulnerable part of it. Once leveraged loans are exposed to risks, it will create destructive impacts as serious as those of sub-prime mortgage during the 2008 financial crisis.

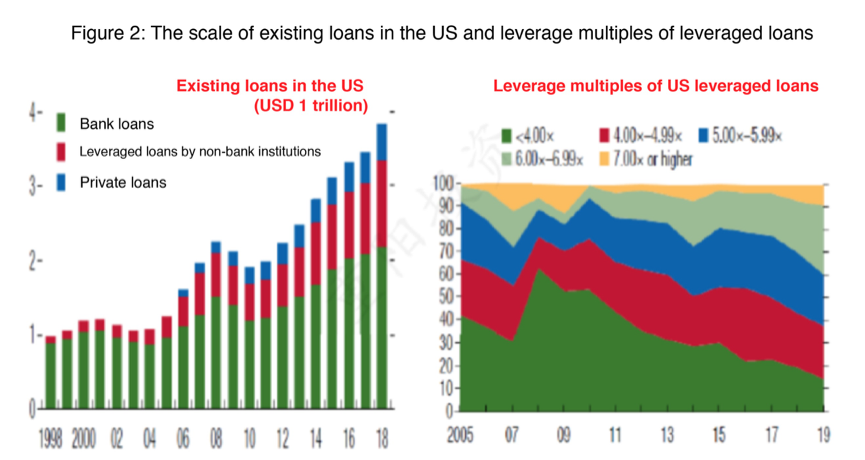

Leveraged loans, in short, are loans to institutions with weak credit qualifications, which are somewhat similar to junk bonds in the bond market. At present, the volume of leveraged loans in the United States is rather large. The size of existing loans in the US can be seen from the left part of Figure 3. Existing loans fall into three categories: One is bank loans, which are usually provided to enterprises for business activities; the second is leveraged loans from non-bank institutions; the third is private loans.

It can be seen that the scale of leveraged loans by non-bank institutions has grown rapidly since 2008 and has now exceeded USD 1 trillion. Such loans are usually not used to support industrial and commercial activities, and most of them are used for capital market operations, such as mergers and acquisitions or stock repurchases. The cost of leveraged loans is relatively high, so it can only be used for high-yield activities such as capital operations to cover its financing costs.

To a certain extent, the massive accumulation of leveraged loans itself reflects the fragility of the real economy. The return on investment of the real economy is difficult to support such high financing costs.

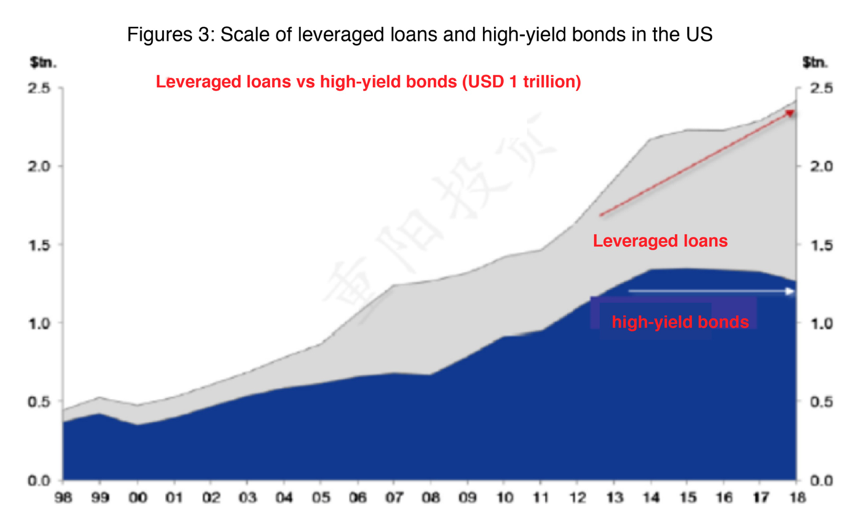

The right part of Figure 2 shows the distribution of leverage multiples of leveraged loans. It can be seen that with the rapid growth of leveraged loans, the leverage ratio of such loans is also increasing, and the share of loans with a high leverage ratio keeps growing. When compared with standardized bond products, especially high-yield bonds, the scale of current US leveraged loans is comparable to that of high-yield bonds, with a size of approximately USD 1 trillion (see Figure 3). The impact of leveraged loans cannot be underestimated. It is an important manifestation of the vulnerability of the credit market.

The vulnerability of the stock market is also worthy of attention.

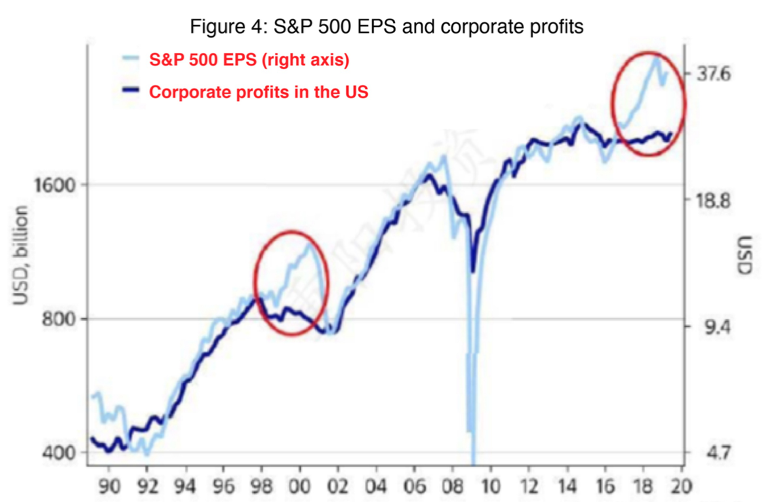

Before the outbreak, the US stock market maintained a ten-year bull run. But an interesting phenomenon behind the bull market is that the overall profits of listed companies have basically stagnated since 2014 while the S&P 500 earnings per share (EPS) saw continuous growth (Figure 4).

There may be two reasons for this phenomenon. One is that S&P 500 companies are large ones. With the increase of their market shares, growth rate of their profits will be higher than that of all companies. Another reason is that listed companies may repurchase stocks in large quantities. As a result, while the total profit remains unchanged, the denominator of the outstanding shares is decreasing, resulting in an increase in EPS.

Data show that stock repurchase of US listed companies has experienced large-scale growth after 2009, which may be an important factor driving the rise in US stock prices.

In 2018, 72% of the cash flow of US S&P 500 companies was used for stock repurchases and 41% for dividends. Sum of the two exceeds 100%, so companies have to borrow to support the above behavior. It is a very interesting phenomenon that borrowing funds does not count as capital expenditures, but these funds are used for repurchasing stocks and distributing dividends, which serve to increases EPS and raises the stock price .

Perhaps the listed companies in the United States have long discovered that they no longer need to use capital expenditures to create profits for shareholders, they can achieve their goals by simply buying back shares and paying dividends. A considerable portion of capital for stock repurchasing comes from the credit market. And this is profitable.

At present, the latest earnings yield of S&P 500 companies is about 6%. When a company borrows from the credit market, such as issuing 3A corporate bonds, the interest rate is only 2.7%. Repurchasing stocks with borrowed money shows plenty of room for arbitrage, especially after 2008. Although the rate of return of listed companies has been declining relentlessly, the interest rate of corporate bonds falls faster, so there are still gains from arbitrage. This is an important reason why stock repurchases have become so common among US listed companies.

In summary, the US economy is very fragile, and the capital market contains inherent vulnerabilities. Therefore, under the impact of the epidemic, capital market prices go through violent turbulences. Recently, we see many news about the turmoil in the US stock market, but what’s less noticeable is that the leveraged loan index has fallen by 30%.

III. The impact of the pandemic has quickly spread in the capital market, and may end the 10-year bull market in the United States

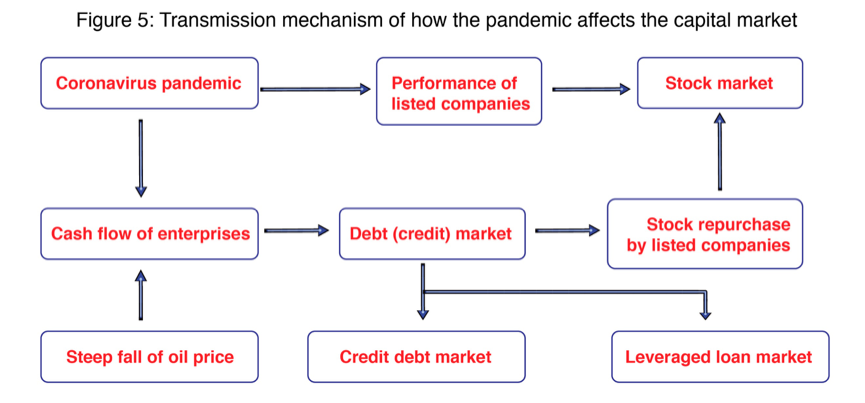

Here is a brief review on the transmission mechanism of how the coronavirus pandemic impacts the capital market:

It's needless to say the coronavirus pandemic is the origin of the shock. It directly impacts the stock market by changing the performance expectations of listed companies, which is a very direct transmission.

At the same time, the epidemic also affects the cash flow of the enterprise. The drastic fall of oil prices on the international market also damages the cash flow of the enterprise. Combination of the two has a direct influence on the bond market, which then indirectly affects the stock market and directly affects the leveraged loan market through repurchase of stocks by listed companies, forming a complete transmission mechanism (see Figure 5).

This is how the pandemic impacts the stock market, the bond market, and the leveraged loan market.

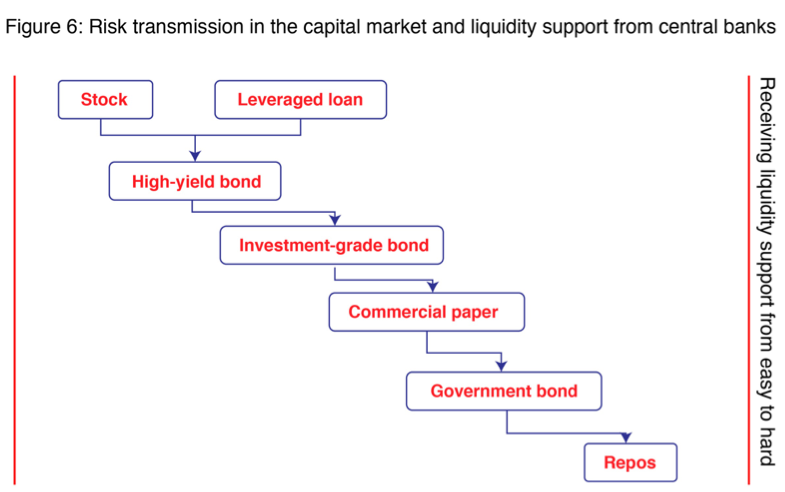

It can be seen that this round of epidemic transmission is from top to bottom, and from direct transmission to indirect transmission. Risks are transmitted from the stock market and the leveraged loan market to high-yield bonds, investment-grade bonds, commercial paper, and government bonds, and finally to the repurchase market (see Figure 6).

However, the intervention and rescue measures by the central banks, that is, injecting liquidity, goes through a transmission process from bottom to top. Government bond and repurchase can directly benefit from central banks' bailout in the open market, and the commercial paper market can also enjoy support in the short term, while investment-grade high-yield bonds can only benefit from it in the medium and long term.

At present, the Federal Reserve's intervention include adopting zero interest rate, quantitative easing and even direct intervention in the commercial paper market. For example, the Fed has recently rolled out the Commercial Paper Funding Facility. In extreme conditions, the Fed can buy stocks directly, like what the Bank of Japan once did.

Fluctuations in the credit spread and the capital price offer a clue of the extent to which the pandemic has shocked the economy.

The recent credit spreads on high-yield bonds and investment-grade bonds have fluctuated violently, with the commercial paper and repo market experiencing similar turbulences that are only less volatile than before and after the financial crisis in 2008.

In the capital market, the interest rate of government bonds has continued to slide, with that of 10-year bonds slashed to below 0.5%—almost a zero interest rate. With the global spread of the virus for the past week or so, shortages in US dollar supplies have become increasingly evident, which pushed up the US dollar index.

It seems that another global financial crisis like the one in 2008 is only one step away—until large financial institutions crash.

This is felt most acutely among market participants. Behind every collapse of financial institutions are stock market stampedes. These can be seen in investors’ choices of strategies and trading activities: in addition to recently increased popularity of risk parity, the market is also seeing an increase in associated automated trading and preference for ETF among investors.

According to Morgan Stanley, the leverage ratio of risk parity investment portfolios has fallen quickly from over 2 in December last year to the current 1 plus level. This shows that for the past period of time, the market has undergone dramatic deleveraging. The strong impact of that on the financial market can also be seen from the consistent vibration in the prices of different assets. However, this consistency has been weaker after it peaked, signaling some positive changes in the market sentiment.

In conclusion, based on observations of the capital market, we tend to believe that the bull run may come to an end in both stock and dollar market in the US no matter if the pandemic triggers a systematic financial crisis or not, because the American repo market has already accumulated sizable risks, not to mention that the fundamentals of the US economy has been performing lackluster recently.

Against this backdrop, the Fed has rejoined the quantitative easing and zero interest rate club, along with the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan. Eased monetary policies will deal a fundamental blow to the American economy in the long run. Bearing the brunt of that blow are the technological and financial sectors where the United States is highly competitive.

It is not hard to envisage that an "absolute zero" interest rate will fundamentally undermine the basic business models of the financial sector in the United States, as it is doing to their European and Japanese counterparts now. It will be very hard for financial institutions to survive in such harsh macroeconomic environment.

IV. The fundamentals of the Chinese capital market remain relatively optimistic, with new investment opportunities emerging under the blow of the pandemic

Since January, the COVID-19 outbreak has dealt three waves of blows to the capital market in China. The first lasted from January 23 to February 20, a period that witnessed the outbreak of the virus and its spread in China; the second wave started on February 21 and lasted to March 10, during which the epidemic began to sprawl across the world; the third hit on March 11, triggering a liquidity crisis in the global capital market and has not come to an end until now. The three waves of blows have exerted different influences on the capital market in China.

In the first wave, the prices of A-shares and H-shares both slumped, with the latter taking a bigger hit, which reflected growing reluctance among investors to take risks; in contrast, the bond market witnessed continuous booms, with the interest rates of Renminbi bonds and offshore dollar bonds issued by Chinese businesses both increasing.

In the second wave, the A-share market has hardly felt any impact, remaining in a sideway trend in the duration; but the H-share market continued its downturn despite the pick-up in the economic fundamentals in mainland China, since it is more sensitive to the global stock market turmoil. The Renminbi bond market kept flourishing, while that of offshore dollar bonds issued by Chinese businesses began to decline because it is entangled with turbulences in multiple real estate markets.

In the third wave, asset prices around the globe saw a massive plunge under the attack of the liquidity crisis. Prices of A-shares dived, while those of H-shares plummeted even more sharply; the Renminbi bond market slumped, while the prices of offshore dollar bonds issued by Chinese businesses collapsed even harder.

The Chinese market has become increasingly interconnected with the global market through multiple trading links including the Shanghai-Hong Kong stock connect, the Shenzhen-Hong Kong stock connect and the mainland-Hong Kong bond connect. As a result, the A-share market and the Renminbi bond market can hardly wall themselves off from the negative impacts of global capital market turmoil. However, it is the offshore market that suffers the direct shocks, which can be seen from the huge fluctuations in the prices of H-shares and offshore dollar bonds issued by Chinese businesses. In this sense, the economic fundamentals in mainland China remain encouraging, despite that they are also subject to the negative spillovers of the global liquidity crisis.

In the current environment, it requires a lot of thinking to spot opportunities and properly engage in investment activities in the Chinese capital market. It totally makes sense to say that there is not any good investment opportunity in the market right now, and there are a lot of reasons to be pessimistic.

But what we need the most amid the pandemic's blow is objective, dispassionate analysis of the current situation to avoid the contagion of pessimism and self-induced panic. I hereby share with you some of the observations we have in Shanghai Chongyang Investment based on our macro asset allocation model, which has been applied for a long time.

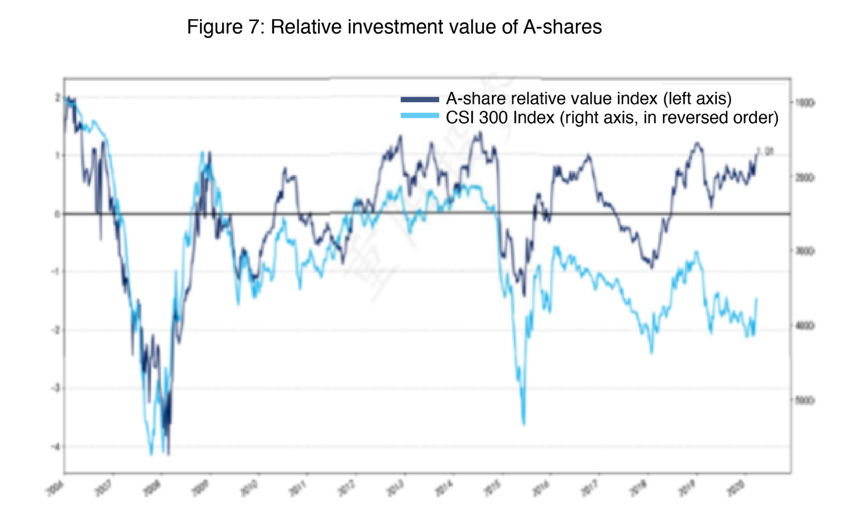

An important indicator in the model is the relative investment value of the A-shares, which, according to our estimate, has uplifted to a rather high level through previous adjustment in the market (see Figure 7). "0" in the left vertical axis in Figure 7 stands for the neutral level of investment value, while the other numbers are standard deviations from the neutral level that demonstrate how the stock market performs. It is clear that the current investment value of A-shares is nearing its all-time high.

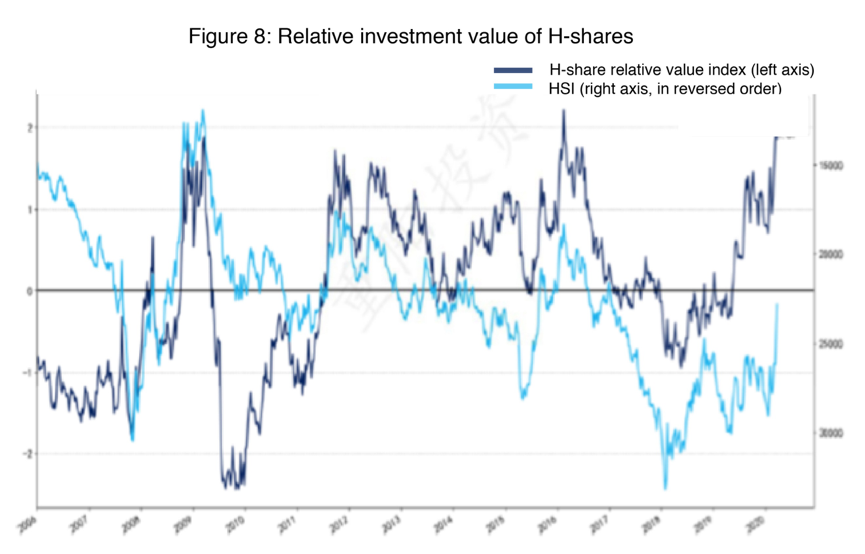

Doing even better are H-shares, whose investment value has shot up to a level second only to that in 2016, with a positive standard deviation of nearly 2. This value can be matched only by those back in 2009 and 2016 (see Figure 8).

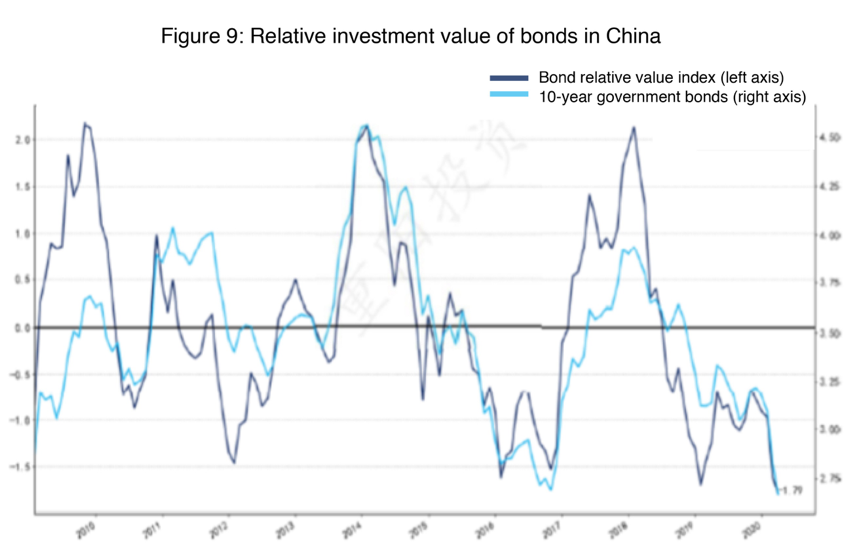

Only the investment value of the bond market in China is relatively low at present (see Figure 9).

This estimate, if reliable, implicates that it is very worthwhile to invest in the Chinese capital market, especially the stock market, and the reasons are simple: facing the interwoven shocks to both the economy and public health, the level of uncertainties in China is relatively lower than in most other countries, and China has a huge potential to cope with the negative impacts successfully given its efficient control of the virus, and quick, effective policy responses.

Most of the pessimistic factors have already been reflected in the previous declines of stock and bond prices, so there is no need to be too pessimistic about the Chinese capital market in the near future.

The above analysis is grounded on observations of asset price fluctuations and some of the fundamental factors in the Chinese economy. But in addition to these short-term factors, investors should pay equal attention to medium- and long-term indicators.

Among all medium- to long-term factors shaping the asset prices, I would like to talk in particular about the debt cycle and the financial cycle. As a matter of fact, the vulnerabilities of the American capital market are interrelated with the debt cycle of the country.

The concept of deleveraging has been discussed a lot in recent years, with many countries, including China, taking related efforts. But actually, the aggregate leverages of developed countries and mature market economies have hardly dropped. It is other economies that are adding leverage.

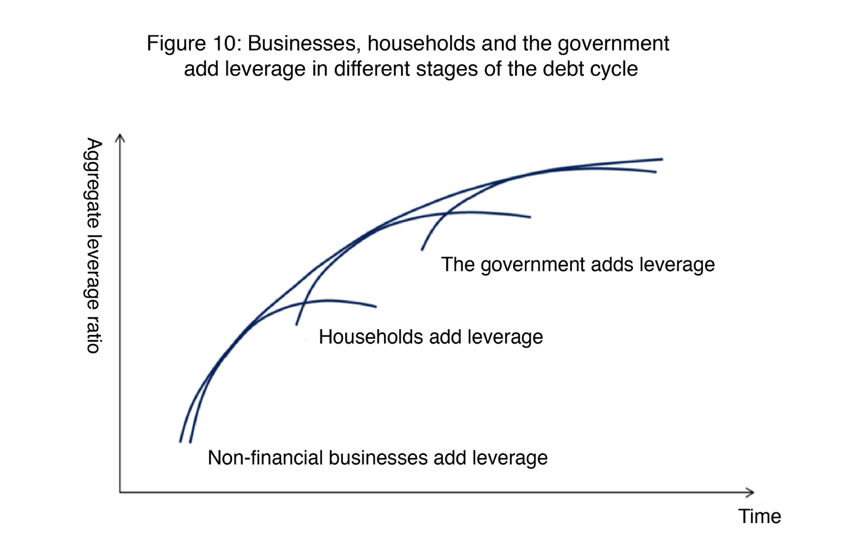

Generally speaking, the non-financial business sector in a country is the first to add leverage, followed then by the household sector, and finally, the government sector. Therefore, the debt ratio of a country is strongly correlated to its economic development level, and that's why high leverage has become a feature of a developed country.

Most developed European and American countries have entered the stage where the government is adding leverage, while in China, non-financial businesses remain the major borrower, which means that the country is still in the first stage of the debt cycle. Through the horizontal comparison, it is clear to see that the leverage ratio of the household sector in China is near global average, while that of the government is on the lower end of the spectrum.

Ray Dalio, in his iconic book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, has offered a detailed analysis of macroeconomic problems that incorporates his observations of the capital market responses. This book is very helpful for investors and serves as a guidance for understanding current issues in the Chinese capital market. He divides the deleveraging cycle into different stages, with the share price, the interest rate (bond) and the exchange rate (current account) showing varied performances at each stage.

Based on this analytical framework, we have tried to take stock of this wave of deleveraging efforts in China, and reached the conclusion that the country is currently at the late stage of the "depression period" and getting close to wrapping up its deleveraging drive. This judgement is of key significance.

Combining our observations of the debt cycle and the financial cycle, we believe that there is rather limited space for the share price in China to go down further, because it is nearing the end of the depression period. In comparison, the interest rate still enjoys leeway for further declines in the long term. The fundamentals of Renminbi exchange rate remain sound, because it is not likely that the current account that is basically balanced right now will see greater deficit. Instead, it may reap a slight surplus.

To sum up, the COVID-19 outbreak has had huge impacts on the global economy, and asset prices have responded violently as a result. China has also felt the blow, but its efforts to contain the epidemic have been quite effective, and its economic fundamentals remain relative optimistic. That have supported the investment value of the Chinese capital market, especially the stock market.

Despite that the above judgement may turn out to be wrong, we still believe that the potential returns of investing in the Chinese capital market are higher than the potential risks; based on this observation, we suggest that investors remain optimistic and actively participate.

There are many predictions and analysis of the market situation at the moment. We believe that the pandemic, no matter how it evolves, is essentially a supply-side shock. The question of whether we can defeat COVID-19 is difficult to answer scientifically, but we need a bit of faith to carry through.