Abstract: Since 2022, there has been a significant increase in deposits in Chinese residents' bank accounts, with a substantial portion of the additional savings believed to be "excess savings." To understand whether "excess savings" exist in China, the authors reference the experience of the United States and examine basic phenomena, concepts, and theories. They conclude the Chinese household sector does not have "excess savings" as the disposable income of China’s household sector has not experienced unexpected growth, and analyze the macro implications of the increase in the intentional savings rate among households.

Since 2022, there has been a significant increase in deposits in Chinese residents' bank accounts, with a substantial portion of the additional savings believed to be "excess savings." To understand whether "excess savings" exist in China, we need to reference the experience of the United States and examine basic phenomena, concepts, and theories.

The direct and primary reason for the formation of "excess savings" is the substantial increase in disposable income of the household sector due to the massive subsidies provided by the US government in 2020-2021. The household sector did not spend the unexpectedly higher income all at once, primarily because residents' consumption behavior exhibits the characteristics of smooth consumption predicted by the "permanent income hypothesis." This led to the continuously accumulating "excess savings" before August 2022 and depleting "excess savings" after August 2022.

Considering the experience of the US household sector, our viewpoint is that the Chinese household sector does not have "excess savings" as it lacks the conditions necessary to form such savings. The main reason is that the disposable income of China’s household sector has not experienced unexpected growth. Additionally, we have not observed at the macro level the substitution effects caused by restricted consumption scenarios, nor does the pace of consumption correspond well with the pace of restricted consumption.

One conjecture for the increase in the savings rate is that Chinese households have adjusted their expectations for medium- and long-term income. After downward adjustments in income expectations, consumption will see a greater decline than short-term income fluctuations. In this case, the increase in savings fundamentally reflects an increase in the intentional savings rate – the rising savings rate of the current household sector is the result of reaching a new steady-state level and does not involve so-called "excess savings."

The increase in the intentional savings rate among households also has several macro implications. Firstly, it is advisable to cautiously estimate the strength of consumption growth for this year and the near future without assuming that consumption levels will simply converge to the previous trend. Secondly, the consumer price index is expected to remain stable, but the profit margins of downstream companies may be squeezed. Thirdly, the increase in the intentional savings rate will lead to a downward shift in the risk-free interest rate and also bring pressure on asset allocation. The possibility of an "asset shortage" may reemerge. Fourthly, the trade surplus may expand again, leading to new pressures in international economic and trade frictions.

Since the end of last year, major international institutions and many businesses have been optimistic about the recovery of China's consumption in 2023. The reasons behind this optimism are straightforward. Firstly, daily life is returning to normal, which means that previously suppressed activities such as tourism, travel, dining out, shopping, and attending concerts are expected to rebound. Secondly, there has been a significant increase in deposits in Chinese households' bank accounts, and a considerable portion of these additional savings is believed to be "excess savings" beyond normal levels. If these "excess savings" are converted into consumption, they can have a substantial boosting effect on overall consumption. With the ability to engage in normal consumption and the availability of "excess savings" for spending, the consumption outlook for 2023 appears promising.

Similar phenomena have occurred in the United States as well. In 2020-2021, the US experienced a sharp increase in household savings rates and a significant rise in bank deposits, resulting in the accumulation of over $2 trillion in "excess savings." Subsequently, these "excess savings" supported a strong consumption recovery in the US.

Therefore, the question of how much "excess savings" exist in China is not only of macroeconomic importance but also holds significant policy implications. Many institutions have already conducted careful and detailed estimations on this matter. Although their methodologies may differ, they generally follow a similar approach: first, estimate the trend value of bank deposit growth under normal circumstances and then make necessary adjustments. These adjustments account for factors such as the conversion of wealth management products into deposits and the funds that were intended for housing purchases but ultimately ended up as savings. Through these adjustments, they arrive at a value representing "normal savings." The portion of actual savings exceeding this "normal savings" can be considered "excess savings." Due to the reliance on certain assumptions for these estimations, data variations exist among different institutions.

We have also devoted serious thought to the issue of "excess savings." We believe estimating "excess savings" requires appropriate reference to the US experience and a foundation in basic phenomena, concepts, and theories to arrive at a more reasonable conclusion.

Ⅰ. EXCESS SAVINGS IN THE US HOUSEHOLD SECTOR

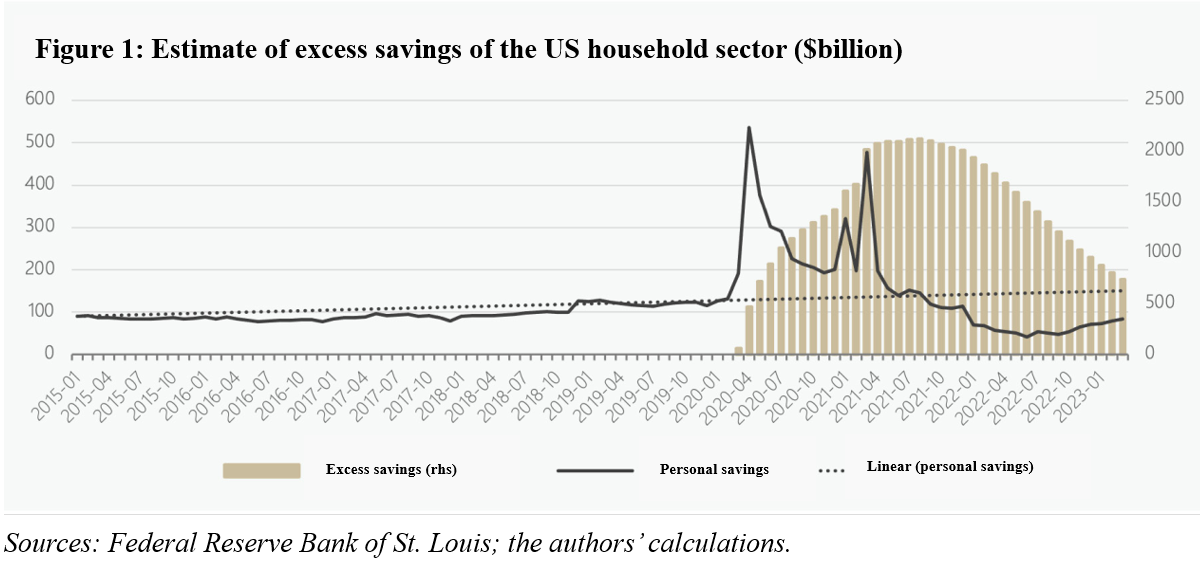

Figure 1 depicts the monthly savings of US households and our estimated balance of "excess savings" for US households based on this data. It can be seen that prior to March 2020, US households’ savings were consistently around $100 billion per month, gradually increasing. From March 2020 to August 2021, savings were significantly higher than the trend value, but afterward, savings began to fall below the trend value. We interpret the difference between household savings and the trend line as "excess savings." Before August 2021, "excess savings" continued to increase, reaching a peak value of $2.12 trillion. Subsequently, "excess savings" began to deplete, decreasing each month. By March 2023, "excess savings" amounted to $74 billion.

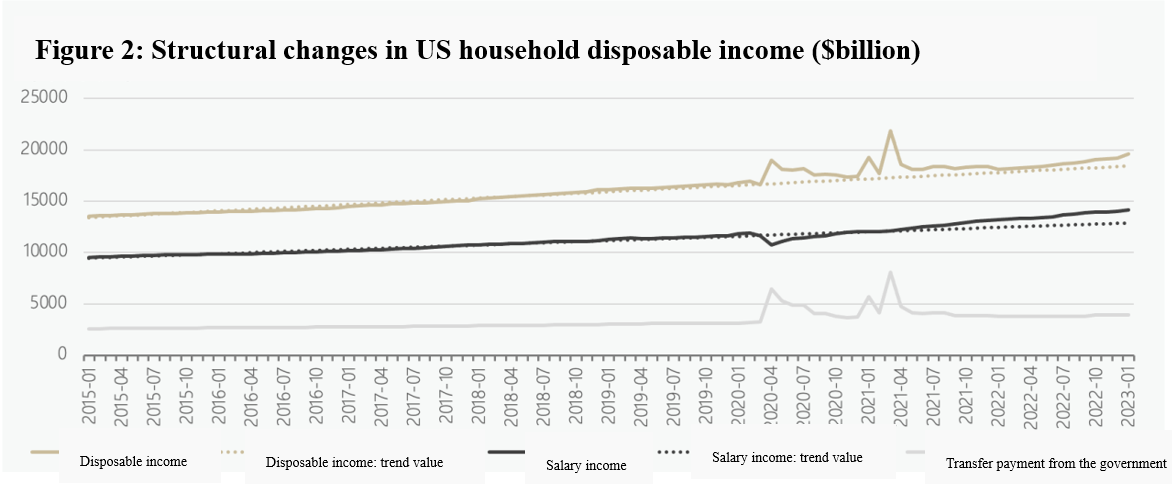

The main and direct reason for the formation of "excess savings" in the US household sector was the significant increase in disposable income due to the massive subsidies provided by the US government during 2020-2021. The US government implemented three large-scale direct subsidies to the household sector. As shown in Figure 2, although the wage income of US households experienced a significant decline in early 2020 and remained below previous levels for a period of time, the disposable income of US residents, taking into account government transfer payments, saw an extraordinary growth during 2020-2021, consistently surpassing the previous trend level.

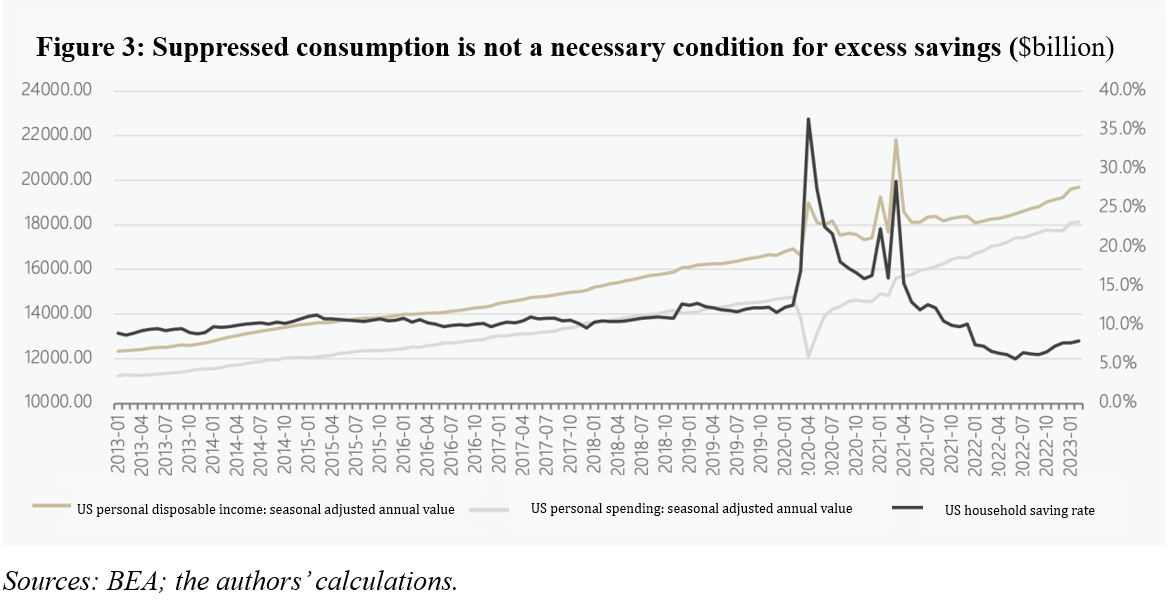

The pace and intensity of government subsidies are highly consistent with the changes in the US household savings rate. As shown in Figure 3, a significant portion of the unexpected disposable income generated by government subsidies is converted into savings by the US household sector. By examining the US consumption data, we can observe that the first peak in the household savings rate resulted from a combination of the unexpected increase in disposable income and a significant contraction in consumption due to the pandemic. However, the second and third peaks in the savings rate corresponded to periods of unexpected growth in disposable income and recovery in consumption. This evidence suggests that unexpected changes in income are the more direct and primary cause of "excess savings." While the temporary restraint on consumption caused by the pandemic also contributes to passive savings, it is not a necessary condition.

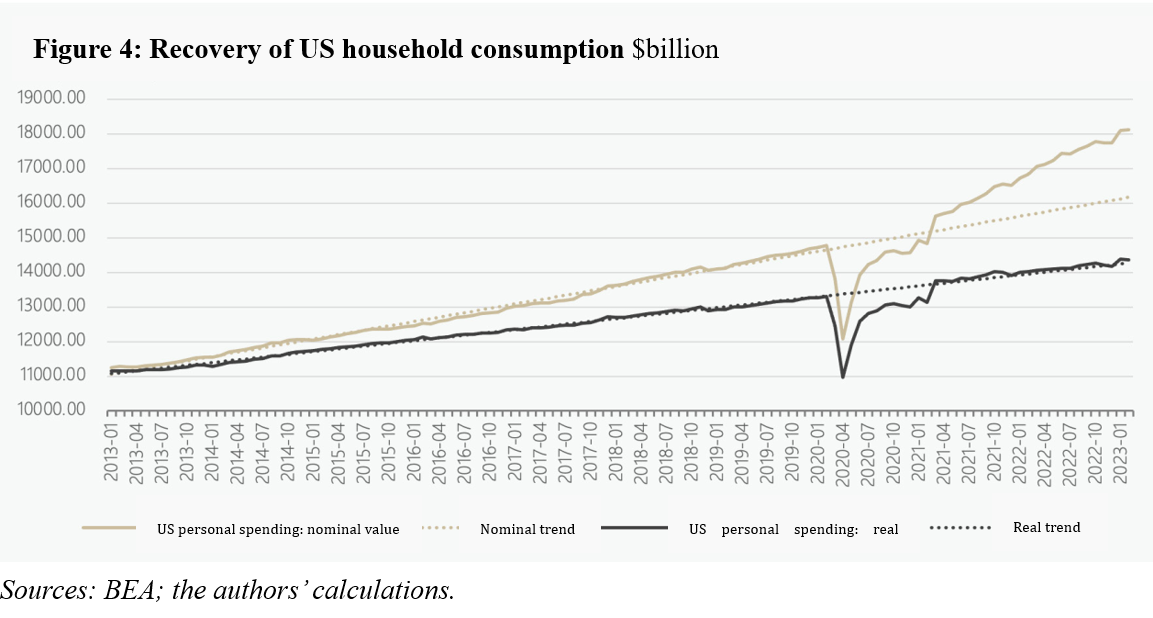

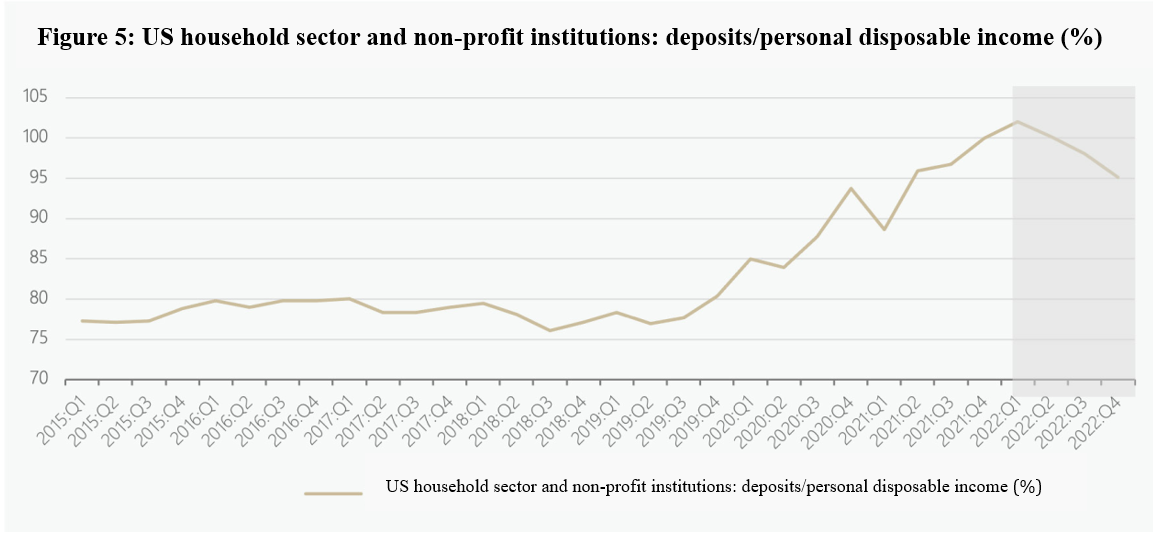

From another perspective, after the decline in fiscal subsidies, the current savings rate of the US household sector has rapidly decreased, and the previously accumulated excess savings are gradually being consumed. As shown in Figure 3, the savings rate of the US household sector began to decline rapidly in 2022 and has remained below the normal level. During the same period, the constant-price expenditure of US households has been maintained at the previous trend level, while nominal consumption has been much higher than the trend level (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 5, the proportion of savings deposits to personal disposable income in the US has rapidly increased during the phase of accumulating excess savings. During the phase of declining savings rate, the proportion of deposits to consumption has started to decline, but it remains below the pre-pandemic level.

Therefore, the story behind the "excess savings" in the US is rather straightforward: the substantial transfer payments by the US government to the household sector in 2020-2021 resulted in an unexpected increase in disposable income for households. However, households did not spend all of the unexpected income at once. Part of the reason is the limited consumption opportunities during a certain period. However, the more fundamental reason is that household consumption behavior still exhibits the characteristic of smooth consumption predicted by the "permanent income hypothesis." As a result, the phenomenon of continuously accumulating "excess savings" before August 2022 and gradually depleting them after August 2022 emerged. The outcome of this process is that the actual consumer spending in the US has fully returned to the previous trend or even slightly exceeded it. However, due to the simultaneous high inflation, nominal consumer spending in the US has far exceeded the previous trend level.

Ⅱ. THE ORIGIN OF THE DISCUSSION ON CHINA'S "EXCESS SAVINGS"

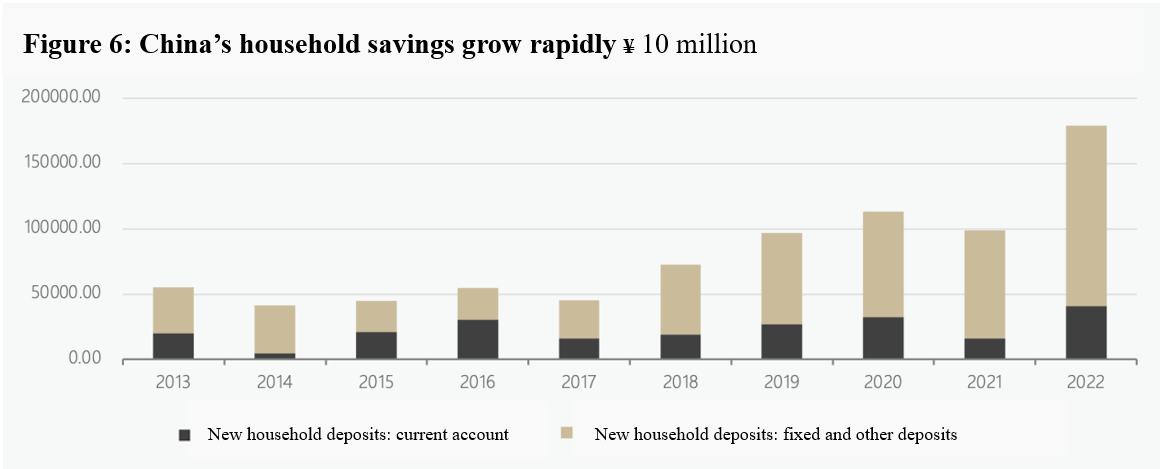

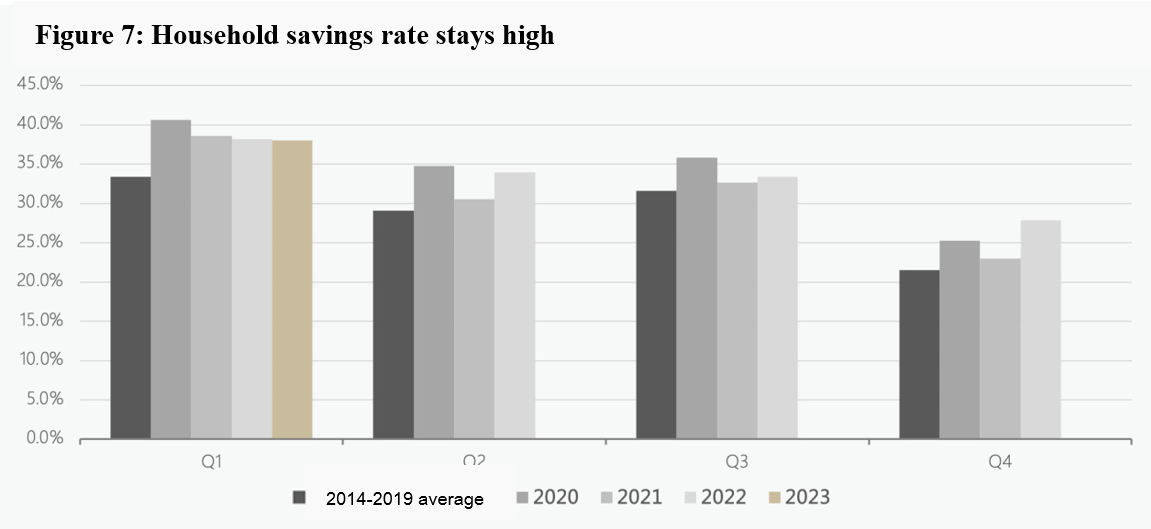

Since 2022, new deposits in China's household sector have been rapidly increasing, significantly surpassing the trend levels of the past decade. As shown in Figure 6, in 2022, the new household deposits in China amounted to 17.9 trillion yuan, which was 8 trillion yuan more than in 2021. Among them, new household time deposits accounted for 13.8 trillion yuan, which was 5.5 trillion yuan more than in 2021. In the first quarter of 2023, China's new household deposits reached a high of 9.9 trillion yuan, an increase of 2.1 trillion yuan compared to the same period last year. The significant increase in household time deposits is accompanied by a rise in the household savings rate . As shown in Figure 7, China's household savings rate exhibits clear seasonal effects, with a notably higher savings rate in 2022. In the first quarter of 2023, China's household savings rate remained at 38%, which is comparable to the same period in 2021-2022 and significantly higher than the average level during 2014-2019.

Many viewpoints suggest that the significant increase in deposits and high savings rate in China indicate the accumulation of a certain amount of "excess savings" by the household sector during the pandemic. However, it is important to consider that deposits do not necessarily equate to savings due to the following three reasons:

First, an increase in household deposits does not always mean an increase in savings. Macroscopically, savings refer to the difference between income and consumption, corresponding to the increase in net assets, which is the increase in assets minus liabilities. For example, a family borrows 200,000 yuan in consumer loans, spends 50,000 yuan, and temporarily keeps the remaining 150,000 yuan in the bank. Statistically, the family's deposits increase by 150,000 yuan. However, in economic terms, the family is actually indebted to the bank by 50,000 yuan plus interest, leading to a decrease in savings.

Second, deposits are only a part of households' financial assets, and adjustments in financial asset allocation can cause changes in deposit amounts. Since the second half of 2022, there have been clear signs of funds that were previously invested in wealth management products shifting back to bank deposits. According to information revealed in the People's Bank of China's press conference for the first quarter of 2023, "At the end of March, the total assets of aggregated wealth management products amounted to 94.7 trillion yuan, a decrease of 1.6 trillion yuan from the beginning of the year, with a negative growth rate of 1.7% year-on-year, down by 8.1 percentage points compared to the same period last year." Translating this information into numbers, the balance of wealth management products at the end of March 2023 decreased by 1.6 trillion yuan compared to the end of March 2022, while the balance at the end of March 2022 increased by 5.8 trillion yuan compared to the end of March 2021. The shift from growth to decline in wealth management products accounts for a significant difference of 7.4 trillion yuan, and some of this money has been converted into deposits, leading to extraordinary growth in deposits.

Third, the decrease in major expenditures such as housing purchases can mechanically lead to an increase in household deposits. Zhu He (2022) found that "From January to September 2022, China's residential sales decreased by 3.5 trillion yuan compared to the same period last year. This is roughly equal in magnitude to the change in new household deposits." From a macro perspective, this represents a portion of funds that should have been allocated to housing as expenditures but instead turned into household savings deposits.

Due to these reasons, various market analyses, when estimating the scale of China's "excess savings," generally exclude factors that may increase deposits but not savings based on certain assumptions. After excluding these factors, it is generally believed in the market that China's "excess savings" are not as high as 8 trillion yuan but rather between 1 trillion and 3 trillion yuan. Even if the estimation of the scale between 1 trillion and 3 trillion yuan is approximately accurate, its macroeconomic significance remains significant. If this portion of savings can be converted into actual consumption within one or two years, its impact on domestic demand and growth in China should not be ignored. However, the question is whether this estimation is truly accurate.

III. NO EXCESS SAVINGS IN THE HOUSEHOLD SECTOR

Referring to the household sector of the US, our view is that there are no excess savings in China's household sector, as the conditions causing the phenomenon are basically absent.

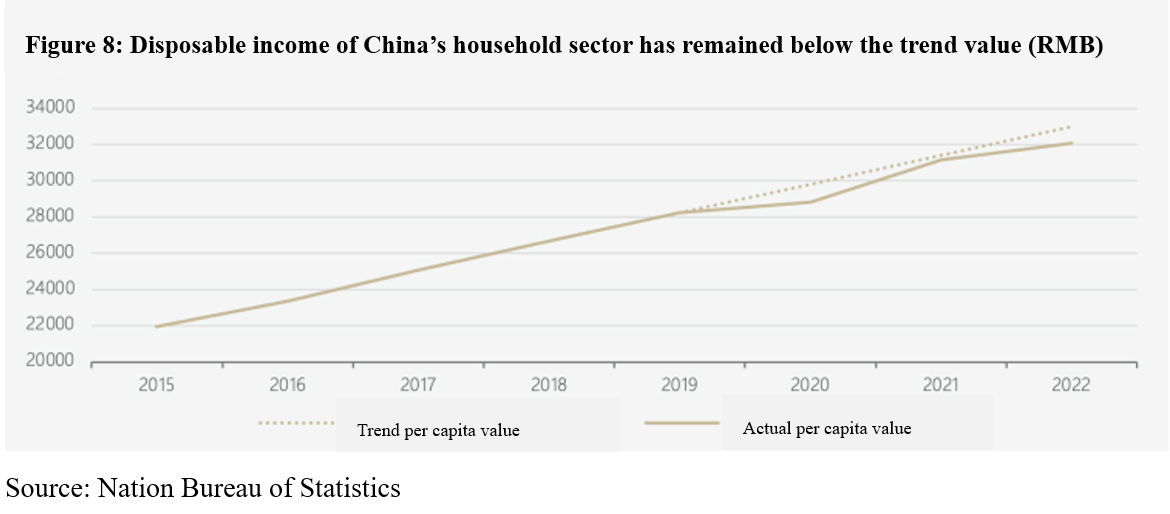

The main reason for this view is that the disposable income of the household sector in China did not experience stronger-than-expected growth in 2022. As shown in Figure 8, disposable income witnessed moderate growth from 2020 to 2022, but compared with that of years before 2019, the disposable income in 2022 was slightly below the trend value. As mentioned earlier, the main factor in the formation of excess savings in the US household sector is an increase in income beyond expectations, which does not hold true in China. Without excess income, it is difficult to imagine where excess savings would come from.

Even if there are passive savings caused by the restricted scenarios of consumer spending, it should be not regarded as excess savings for the reasons below.

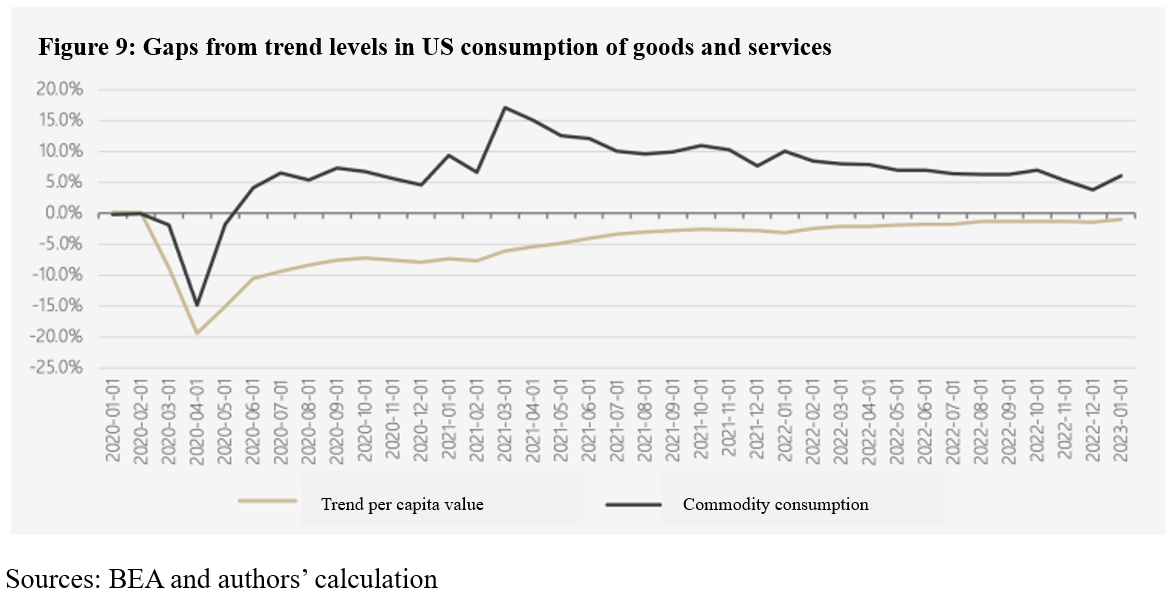

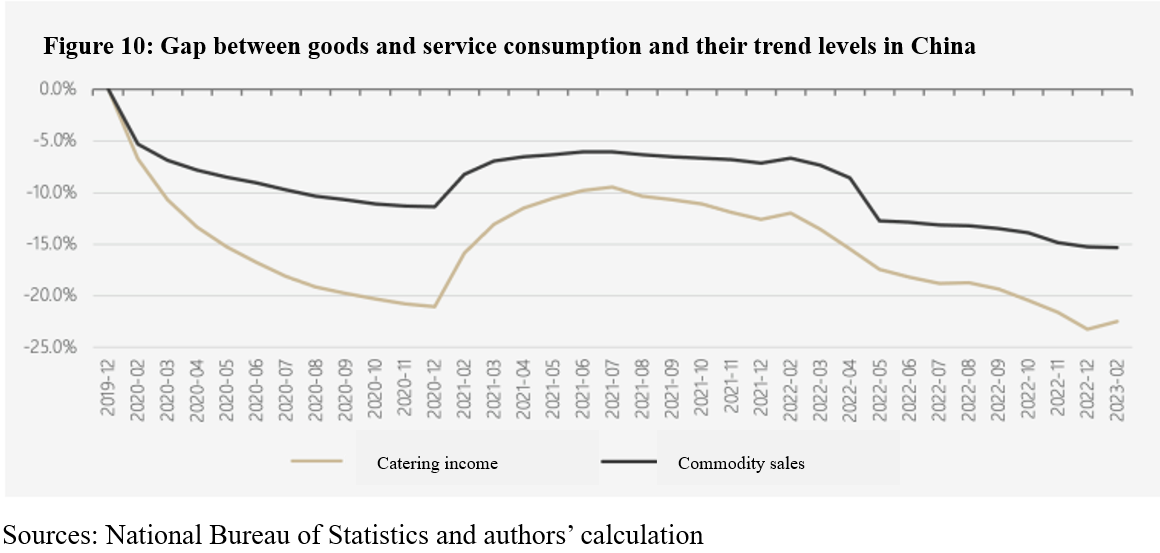

First, there is no substitution effect observed at the macro level due to the restricted consumption scenarios. If consumption only declined due to restricted scenarios, such as contact services, it would make more sense, based on foreign experience with the "home economy," that spending on goods, which is less influenced by consumption scenarios, would increase more rapidly (Figure 9). Though this substitution effect can be observed in some cities and among some population groups, for example, the rising number of people buying high-end bicycles for commuting and exercising, at the macro level, consumption of goods in China has not been stronger, and the trend of consumption of goods is basically the same as that of services (Figure 10). This suggests that slower consumption growth is not primarily, or even not, the result of constrained consumption scenarios at all.

Second, the pace of consumption changes does not correspond to the occurrence of restricted consumption scenarios either. The first and third quarters of 2022 did not see much-restricted consumption scenarios, which were more often seen in the second and fourth quarters. If the phenomenon that "passive saving" turned to "excess saving" did exist, once the consumption restrictions lifted, there should be a significant increase in consumption and a sharp decrease in savings rate. However, this assumption could not hold water. Data for 1Q 2023 further reinforced our view. When consumption did increase significantly year on year during the first quarter of 2023, the savings rate remained high. This suggests that the increase in consumption in 1Q 2023 was not primarily caused by people’s willingness to spend but rather by the recovery of the economy and income growth.

Third, passive savings, if it exists at all, should only be a macroeconomic phenomenon in a relatively short time. To illustrate this, let's do a thought experiment that is far from reality: a person goes to a concert out of town once a month and spends 5,000 yuan a month on it. Since the concert is temporarily unavailable for two months, one will save 10,000 yuan that should have been spent, so this becomes 10,000 yuan in passive savings. If this logic is linearly extrapolated: no concert in three years would result in 180,000 yuan in passive savings; in thirty years, it would result in 1.8 million yuan in passive savings. Obviously, this linear extrapolation does not make sense. If a person can no longer attend concerts in the future 30 years, his or her spending habits will definitely change, and it is unlikely that he or she will simply save the money in the bank account and not spend it. In fact, if one can no longer attend concerts for the next 30 years, one's saving behavior should have nothing to do with concerts anymore. To think about it in an inverse way, despite the fact that Chinese people have enjoyed much richer consumption scenarios in the last few decades than before the reform and opening up, has the savings rate in China fallen because of the increased consumption scenarios? The answer is no. Our point is that the idea of passive saving due to the restricted consumption scenarios may be true at the macro level in a time scale of a few months, but if it were a few quarters or years, such passive saving would have ceased to be passive.

Based on the above discussion, we believe that while it is true that China's savings rate has increased, it cannot be assumed that these savings are excess savings. In other words, we cannot assume that these savings will soon be converted into consumption and that the savings rate will fall back very soon. The increase in the savings rate is the result of a relatively significant change in the consumption-savings behavior of Chinese residents over the past few years.

IV. CHANGES TO INCOME EXPECTATIONS IN THE CHINESE HOUSEHOLD SECTOR IS THE KEY TO UNDERSTANDING THE INCREASE IN SAVINGS RATE

One of our speculations about the rise in the savings rate is that Chinese residents have adjusted their expectations of medium- and long-term income.

Any standard macroeconomics model in textbooks would tell the following two things: first, consumption is a function of (permanent) income; second, consumers have a tendency to smooth consumption, that is, to keep their consumption path basically stable. Based on such two basic behavioral models, let us imagine the following three different scenarios: Scenario 1: income growth is temporarily higher than expected; Scenario 2: income expectations are temporarily lower than expected; Scenario 3: income expectations are adjusted downward (or upward). A standard macroeconomic model would conclude as follows:

Scenario 1: Excess savings would occur during periods when people’s incomes are temporarily higher than expected, after which the excess savings would be slowly consumed. The case of the United States described above is more in line with Scenario 1.

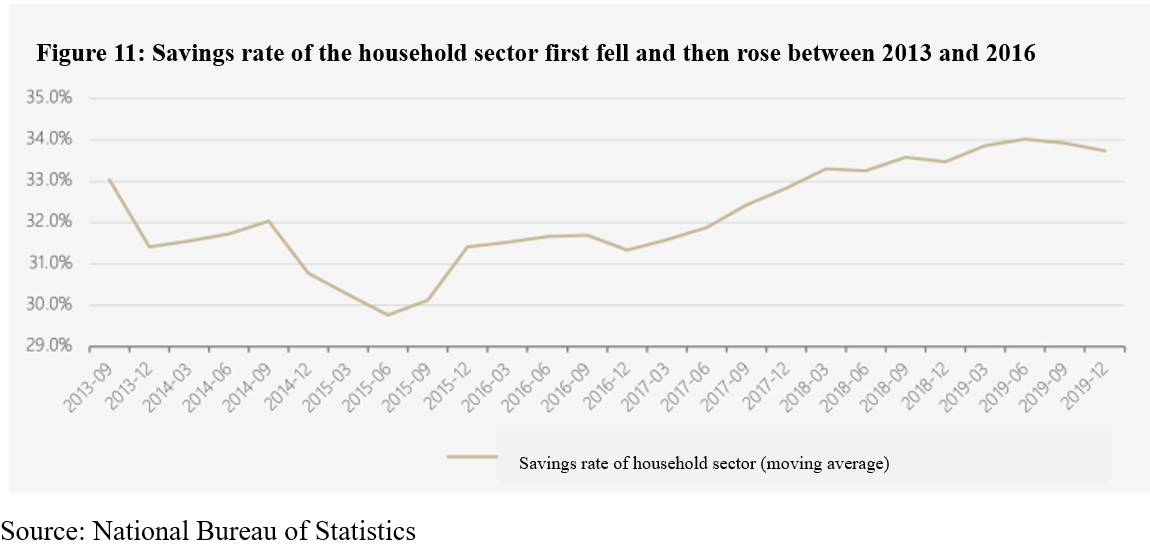

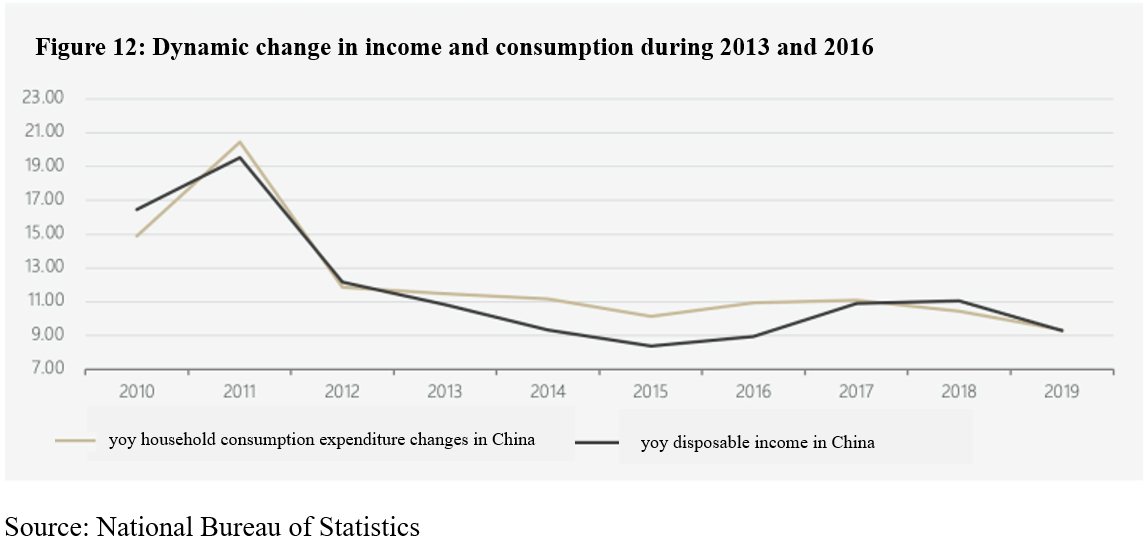

Scenario 2: Negative excess savings occur during periods when incomes are temporarily below expectations, after which the negative excess savings would be gradually replenished. After the third quarter of 2013, the economic growth in China slowed, and the growth of disposable income continued to decline. The main factor driving the economic downturn at that time was the decline in real estate investment, with house prices falling for 15 consecutive months. However, as income expectations did not change in the medium to long term, the growth of residential consumption did not fall significantly, but the savings rate fell. In 2016, the macro economy started to pick up, and the savings rate of the household sector gradually returned to the level of 3Q 2013 (Figure 10).

Scenario 3: A downward (or upward) adjustment in income expectations is usually followed by a larger downward (or upward) adjustment in consumption in the short run and a one-time increase (decrease) in the savings rate. During 2020-2023, disposable income growth deviates from its trend value, triggering a reassessment of the medium- to long-term income outlook. If this is the case, residents will adjust their intertemporal asset allocation. At this point, the rise in savings is essentially the result of an increase in the desired savings rate. That is to say, the current increase in the savings rate of the household sector reflects a new steady savings level instead of the so-called excess savings.

V. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The authors of this paper believe the increase in the savings rate of the household sector at the current stage mainly reflects the rise of desirable savings rate, the reason behind which is the change to long-term income expectations and the consequential adjustment of people’s consumption behavior. So we say that excess savings do not exist in China, and the current increase in savings will not be tranverted to consumption expenditure automatically.

The increase in the desirable savings rate of the household sector has many macro implications.

First, it is recommended to prudently estimate the strength of consumption growth this year and in the future. Consumption will increase with income rebound, and consumption items that have been suppressed in the past few years will recover. However, we should neither be too optimistic about the strength of overall consumption growth nor linearly extrapolate the recovery of some consumption items in the past few months to all consumption types or future consumption growth. It is not advisable to simply assume that consumption levels will converge to the previous trend. Sustainable consumption growth ultimately depends on a more considerable improvement in income expectations.

Second, the consumer price index is expected to remain relatively stable, and the profit space of downstream enterprises is easy to be squeezed. If consumption maintains moderate growth, taking into account China's supply and demand landscape, China's consumer price index is expected to remain relatively stable; there will be no significant inflationary pressure. This also means that the bargaining power of downstream enterprises is limited, which will also impact the growth of manufacturing investment.

Third, a rise in the desired savings rate brings about a downward shift in the risk-free interest rate. With other conditions remaining unchanged, more savings targeting at the same assets would bring about an increase in asset prices and a downward shift in returns. However, given the current high level of risk aversion, it is likely that more savings will primarily pursue safe assets, including bank deposits, government bonds, wealth management products of lower risks, and money market funds, as well as some insurance products. The result of this behavior will lead to a downward shift in the risk-free interest rate. But this will also bring pressure on asset allocation, and as a result, asset shortage may reemerge.

Fourth, external surplus may expand, leading to new pressure from global economic and trade frictions. At the macro level, when the savings rate rises, the current account is bound to expand if domestic investment does not rise correspondingly. At the micro level, enterprises will be more active in expanding overseas markets in the face of moderate domestic demand and unchanging prices. These will all lead to the expansion of China’s external surplus, especially the trade surplus in goods. In the context of sluggish economic growth in many countries around the world, the expansion of China's external surplus will inevitably cause discontent among some interest groups and increase the possibilities of economic and trade frictions.