Abstract: This article analyzes the cause of the divergence between social financing and inflation in China. The calculations reveal that the increase in social financing, excluding interest payments, is not as significant as it seems. It should thus be recognized that the significant expansion of social financing in the past three years has played an important role in stabilizing economic growth. However, compared to the shocks and challenges faced by the economy, especially the decline in private sector demand, the increase in new social financing is not excessive but insufficient.

The divergence between social financing and inflation has sparked widespread discussion in the past period. There are currently at least five popular explanations for this issue, but none of them seem to be able to explain where the money is. Simple calculations reveal that the increase in social financing, excluding interest payments, is not as significant as it seems. Without the expansion of new social financing in the past three years, the corresponding GDP growth rate would be even lower. Nevertheless, the economic growth rate in the past three years is still low, considering the potential growth rate of China's economy.

We believe the question "Where is the money?" may be fundamentally flawed. The abundance of money should be judged by a relative reference point, and that reference point should be the intensity of the shock and the resulting demand gap. Cross-national comparisons reveal that the increase in new social financing is not too large considering the negative shocks faced by China's economy. In 2022, China's public and quasi-public sectors leveraged their strength, but only to make up for a portion of the private sector's demand gap. Given the size of the economic gap, the money might be insufficient rather than excessive.

Therefore, we should recognize that the significant expansion of social financing in the past three years has played an important role in stabilizing economic growth. However, compared to the shocks and challenges faced by the economy, especially the decline in private sector demand, the increase in new social financing is not excessive but insufficient.

Between high inflation and low inflation, we should be more concerned about low inflation. The financial market may not be able to wait for the large amount of incremental funds that have not yet been released. In the context of downward pressure on the economy, the level of social financing that supports reasonable economic growth may need to be much higher than previously thought. The policy orientation of "maintaining the basic match between the growth rate of social financing and the nominal GDP growth rate" may indicate the need to increase the basically matched floating space.

I. WHY IS THERE A QUESTION ABOUT “WHERE IS THE MONEY?”?

Below is a virtual example we have created about Country X.

These are the key economic indicators for Country X in Year Y. We will refer to the currency unit of Country X as "guan". In Year Y, Country X's GDP growth rate was -2.8% (compared to 2.3% growth in the previous year), and the average inflation rate was 1.2% (compared to 1.8% in the previous year). In that year, Country X's fiscal deficit reached 2.95 trillion guan, accounting for 14% of GDP. In contrast, while in the previous year, the fiscal deficit accounted for only 5.7% of GDP, and the absolute amount of the fiscal deficit in Year Y was 1.72 trillion guan, higher than the previous year. Country X's broad money supply (M2) grew by 24.9% in Year Y compared to the previous year, adding 3.84 trillion guan, while M2 grew by only 6.4% in the previous year, adding 0.92 trillion guan.

Country X's economic indicators may be extremely confusing. It is clearly a country that has adopted aggressive monetary and fiscal expansion policies, but its GDP growth is negative, and its inflation rate has not skyrocketed but has become even milder. Looking at this set of economic data, can you tell where Country X's money is?

Now let's look at some real data:

In the whole year of 2022, China's new social financing was 32 trillion yuan, and the balance of social financing increased by 9.6%. In the same year, China's actual GDP growth rate was 3%, and its nominal growth rate was 5.3%, with a nominal GDP absolute value increase of 6.1 trillion yuan. In 2022, China's CPI inflation rate was 1.96%, the PPI inflation rate was 4.1%, and the inflation rate corresponding to the GDP deflator was 2.3%.

From 2020 to 2022, China's cumulative new social financing was 98.2 trillion yuan, and the balance of social financing increased by 37% over the three years. In the same three-year period, China's actual GDP increased by 14%, nominal GDP increased by 22.7%, and the absolute value of nominal GDP increased by 22.4 trillion yuan. In the same three years, China's CPI increased by 3.4%, core CPI increased by 1.9%, PPI by 9%, and the inflation rate corresponding to the GDP deflator increased by 8.7%.

In the first quarter of 2023, China's new social financing reached a record high of 14.5 trillion yuan, while in the same period, China's actual GDP growth rate was 4.5%, and inflationary pressures further declined. In April 2023, China's CPI increased by only 0.1% year-on-year, and PPI decreased by 3.6%.

From 2020 to 2022, the 98.2 trillion yuan increase in social financing corresponded to a 22.4 trillion yuan increase in nominal GDP, with every 4.5 yuan of new social financing corresponding to 1 yuan of nominal GDP growth, a significantly higher ratio than the average ratio of 3.2 yuan of new social financing corresponding to 1 yuan of nominal GDP growth from 2013 to 2019. Moreover, China's prices have remained stable without inflationary pressures in the context of high global inflation.

Many people wonder: With so much money, why is there no inflation? Where is the money?

II. WHY DO THE POPULAR EXPLANATIONS FAIL TO ANSWER THE QUESTION “WHERE IS THE MONEY?”?

There are currently at least five popular explanations for this question, but none of them seem to be able to explain where the money is.

1. The money multiplier is decreasing, indicating a slowdown in the rate at which money is created by money. This is due to people choosing to save money rather than spend it. However, the money multiplier only measures the relationship between the monetary base and M2, which is irrelevant to social financing and inflation. In reality, social financing has increased, and inflation is relatively mild. The money multiplier cannot change the fact that social financing is relatively high while inflation is not significant.

2. The efficiency of incremental funds is decreasing. Most bank funds go to state-owned enterprises and local urban investment platforms. However, the economic benefits generated by the funds are not strong enough, leading to a decrease in the investment multiplier. From the perspective of current purchasing power, the increase in social financing directly corresponds to the increase in current purchasing power, regardless of ownership. For example, if a bank lends 1 million yuan to both state-owned and private enterprises and they both spend the loan, such as increasing investment, the increase in current purchasing power brought by them will be the same. The GDP created in terms of accounting will also be equal. Although private enterprises' investment projects may generate higher future returns or have higher capital utilization efficiency than state-owned enterprises, this has no immediate effect on the creation of current purchasing power. This is similar to the case in Keynesian economics, where there is no significant difference in the effect of economic stimulus between using fiscal stimulus to dig a hole and fill it up or to make more efficient investments.

3. Part of the incremental funds did not enter the entity sector to generate actual demand. Instead, it was accumulated in various ways within the financial system, a phenomenon known as "fund idling." However, the basic concept behind the statistical indicator of social financing is the financing from the financial sector to the entity sector. The circulation of funds between financial institutions is not included in the statistics of social financing, so there are no idle funds. Moreover, the concept of "fund idling" is weak. If all transactions in the secondary market are considered "fund idling," will the primary market alone be sufficient in the future?

5. The rapid decline in inflation is due to the base effect. The recent decline in CPI mainly comes from food and energy, and CPI will rise after the base effect disappears. However, there has been no significant inflation in the past three years, which is unrelated to the base effect. We can use core CPI to reflect the inflation situation, which avoids the disturbance of food and energy prices. The downward pressure on inflation reflected by core CPI is more obvious than that of CPI.

6. Social financing is a leading indicator, while CPI is a lagging indicator. There is a time lag between credit and inflation transmission. Although it took some time from the increase in social financing to the rise in inflation, this round of significant expansion in social financing began in early 2020. Now, it is difficult to imagine that there would be such a lag effect after more than three years.

If none of the above explanations are correct, perhaps it is not a problem of explanation, but rather a problem with the question.

III. IS IT POSSIBLE THAT THE MONEY IS TOO LITTLE INSTEAD OF TOO MUCH?

We believe the question of "where is the money" may be misguided. The amount of money must have a relative reference for us to judge whether it is too much or too little. Considering the economic gap, the money may be too little rather than too much. We can observe this from three perspectives:

First, from a macro perspective, over the last three years, more than 10 trillion yuan each year of new social financing has been used to pay the interest on existing debt. This means the net increase in social financing is not as large as it appears. Social financing can be regarded as a direct measure of China's broad debt stock of the whole society. Except for social financing created by equity financing and bad debt write-offs, the remaining debt is all interest-bearing debt that needs to pay interest. At the micro level, micro-subjects can choose to pay interest from the current year's income or use new debt to pay interest. However, from a macro perspective, if the borrower has not undergone a massive change and debts continue to grow, interest expenses are finally covered by new debt. Moreover, those economic entities with weak cash flow-generating capabilities are highly likely only to be able to maintain existing debt by borrowing new debts to repay old ones. In recent years, these economic entities should remain the mainstream.

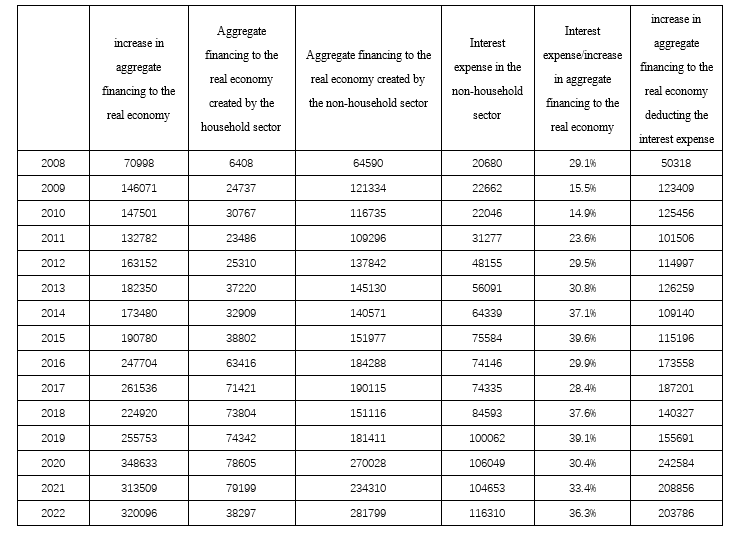

Conservatively speaking, we assume that apart from the household sector (because households that borrow new debt and repay old debt are likely to be different entities), other economic entities can only rely on new debt to pay interest. This part of the debt stock is equal to the social financing stock minus the household loan stock. Then, we use the weighted average interest rate of RMB loans of financial institutions to measure the cost of debt. The results are shown in Table 1.

Since 2008, the scale of interest payments has almost rigidly increased, and the proportion of interest payments to the net increase in social financing has shown an increasing trend. Since 2014 , the ratio of interest payments to the net increase in social financing has remained around 40%, and in some years, it has even been close to 50%. Over the past three years, the cumulative proportion of interest payments to the cumulative net increase in social financing is 36%. Moreover, the volatility of the net increase in social financing after deducting interest payments is significantly larger than that of the original net increase in social financing, which more accurately reflects the macroeconomic situation at the time. It should be emphasized that with the continuous growth of the social financing stock, the net increase in social financing after deducting interest payments is not as large as it seems, which means that there may not be as much money as we imagined. For example, the difference in the net increase of social financing between 2022 and 2012 is 16 trillion yuan, but after deducting interest payments, the difference between them is only 9 trillion yuan.

Table 1 Increase in aggregate financing to the real economy and interest expense during 2008-2022 (every billion yuan)

Second, the pull-up in the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy in the past three years corresponded to higher GDP growth. According to the calculations in Table 1, with the interest expense deducted, the actual increase in aggregate financing to the real economy was $24.3 trillion in 2020, $20.9 trillion in 2021, and $20.4 trillion in 2022, an increase of $8.7 trillion, $5.3 trillion, and $4.8 trillion, respectively, over in 2019. The scale of the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy has indeed reached a new level. With 2012 as the benchmark that roughly every $3.2 of the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy could be converted to $1 of the increase in nominal GDP, these additional increases in aggregate financing to the real economy corresponded to additional nominal GDP growth of about $2.72 trillion, $1.66 trillion, and $1.5 trillion. Or conversely, in the past three years, had not the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy reached a new level, the nominal GDP would have been $2.72 trillion, $1.66 trillion, and $1.5 trillion lower than what was achieved. Calculating backward with the GDP deflator, if the scale of the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy had remained roughly the same as in 2019, real GDP growth over the past three years would have fallen by 2.2 percentage points, 1.3 percentage points, and 1.4 percentage points, respectively.

Of course, here we are talking about the correlation instead of a cause-and-effect relationship between the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy and economic growth. The increase in aggregate financing to the real economy was also attributed to the behaviors of economic agents, such as the leveraging-up by the government, enterprises, or the household sector. It was the result of the behaviors of all economic agents (which we will talk about later). Nevertheless, in any case, without the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy rising to a new level in the past three years, the growth rate of real GDP would likely be much lower than what was achieved.

Third, though the step up in the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy corresponded to a higher GDP growth rate, the growth rate was still rather low compared with the potential growth rate of China’s economy. In the past three years, the average growth rate of China’s real GDP was a hard-won result of less than 4.5% per year. But unfortunately, this growth rate was rather low compared with the potential growth rate of China’s economy. At least, it is hard to prove that the past few years witnessed normal growth rates. But without the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy rising to a new level, according to our calculations, the average growth rate of the past three years would only be less than 3%, which was quite low.

What does that mean? While the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy seemed high and corresponded to a higher economic growth rate, China’s economic growth rates remained lower than normal in the past few years. Therefore, the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy was high only when compared with that of the past. However, over time, in recent years, it has been far from enough as China’s economy faces so many challenges and shocks. That’s why China’s economic growth is still below potential and naturally doesn’t witness inflation.

Then how do we understand the fact that the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy has been far from enough as we face so many challenges and shocks?

IV. LEVERAGING UP BY THE PUBLIC AND THE THIRD SECTORS COULD ONLY PARTIALLY HEDGE AGAINST THE DECLINING INCOME AND DEMAND OF THE PRIVATE SECTOR

One way to understand this issue is to compare across countries. Country X mentioned previously refers to the United States, year Y is 2020, and guan symbolizes the US dollar. Since too many factors are incomparable between China and the US, it’s inappropriate to use a simple analogy here, but at least an order of magnitude can be given.

In 2020, the US used an additional $1.72 trillion in fiscal deficit and an additional $2.82 trillion in macro policy stimulus (M2). Eventually, GDP growth in 2020 was down by 5.1 percentage points over 2019. Please note that the GDP of the US in 2020 was merely $21 trillion. Combining these figures, we can roughly estimate that in 2020, the US suffered a shock accounting for 10-15 percentage points or more of GDP and that the US hedged the shocks to just 5.1 percentage points of GDP, with fiscal and monetary measures that were well over 10% of GDP.

China is facing a shock less severe than that faced by the US, but the shock is also quite significant and will last for a longer period. Compared with such a huge shock, the order of magnitude of the increase in China’s aggregate financing to the real economy does not seem too large. Even if policies and measures are more precise, it is difficult to fully hedge against negative shocks. Therefore, from the perspective of cross-country comparison, the increase in China’s aggregate financing to the real economy is insufficient as China faces such negative shocks.

Another way to understand this issue is to do some simple estimation, not for an exact figure but for an order of magnitude. One general conclusion is that in 2022, the consumption and investment demands of China’s private sector declined compared with the normal growth trend, by an order of magnitude of about $6 trillion.

First, the rise in the savings rate directly led to an increase of about $1.4 trillion in net savings in the household sector, corresponding to a net decrease of $1.4 trillion in consumption demand. In 2022, the savings rate in China’s household sector rose by about 2.1 percentage points over 2021. According to the fact that the disposable income of residents was $70 trillion, it can be seen that the increase in the savings rate brought about $1.4 trillion in new savings. If residents’ spending on housing is also viewed as an investment, then in 2022, the increase in net savings (and the decline in net spending) in the household sector might exceed $3 trillion. Second, the private business sector also witnessed a significant decline in investment demand, the size of which might be at least $3 trillion. In the private business sector, the decline in investment demand came mainly from real estate and some consumer services. In particular, in 2022, real estate investment demand reduced significantly over 2021, but there was no reasonable matching among investments, new construction starts, and sales. Due to the lack of necessary data, it’s hard to estimate the decline in investment demand caused by the decline in new construction starts. But we can briefly look at the most direct part of real estate investment demand, namely, the land-transferring fees paid by real estate, which declined by about 2 trillion yuan in 2022. Besides real estate, the investment demand in living services such as education, medical care, accommodation, and catering decreased significantly in 2022, as well. However, owing to the lack of basic data, it’s difficult to estimate the exact scale. Anyway, the decline in investment demand for living services totaled at least a trillion in order of magnitude.

While the private sector demand fell sharply, the public and the third sectors were leveraging up rapidly. The public sector was financed mainly by issuing three kinds of debts, namely, treasury bonds, local government general-purpose bonds, and local government special bonds, with an increase of about 7.2 trillion yuan. The third sector leveraging was mainly reflected in a series of off-budget financing models. In reality, financing was mainly obtained through local urban investment companies and other financing platforms, of which bank loans and urban investment bonds were the most important financing methods. We roughly calculated the off-budget aggregate financing to the real economy created by the third sector from the perspective of the use of funds (see the appendix for detailed calculations). It turned out the number was about $15.6 trillion. Combining the new debts, the sum amounted to $22.8 trillion, taking up 70% of the increase in aggregate financing to the real economy in the same year (regardless of interest expense, the share of the public sector would be even higher, close to 85%). With the same logic, we calculated that the new debt of the public and the third sectors in 2021 was 20.4 trillion.

In other words, in 2022, the new debt created by the public and the third sectors was only $2 trillion more than in 2021. If the rigid growth in interest expense of the public sector debt is excluded, the marginal contribution was less than $2 trillion.

These estimations are rough, but their implications are clear. In 2022, the public and the third sectors leveraged strongly and played a major role in driving the expansion of aggregate financing to the real economy. Despite that, they only bridged part of the demand gap in the private sector. The increase in aggregate financing to the real economy isn’t low, but considering the huge economic gap, the increase is insufficient. Therefore, it’s easy to understand why we haven’t seen strong demand growth or significant inflationary pressures.

V. CONCLUSION

First, we should realize that the large expansion of social financing over the past 3 years has played an important role in stabilizing growth and helping to keep economic growth within an appropriate range. The expansion is largely due to the leveraging of the public and quasi-public sectors, reflecting the coordination between fiscal and monetary policies. Without the new social financing, it is conceivable that China’s economy would have faced even greater downward pressure.

Second, compared with the shocks and challenges China’s economy is facing, especially the decline of the private sector demand, the scale of new social financing is not excessive but not large enough. Thus, the economy still has a demand gap to be filled. This conclusion is in line with our previous argument of “excessive savings are approximately 0” logically, which means the economy does not have surplus money or savings. If these analyses are right, then all the extrapolations based on the assumption that there is excessive money or savings should be reconsidered.

Third, between excessively high inflation and excessively low inflation, we should worry more about the latter. Just because the scale of new social financing has not fully filled the demand gap in the private sector, we should not worry too much about too much money leading to inflation. Not only does the excessively low inflation reflect the fact that current domestic demand is still insufficient, the bigger risk is that if some more negative shocks occur, our domestic demand and policy space will be further squeezed, given the already low level of inflation.

Fourth, I am afraid that financial markets would not see a large amount of incremental money that has not yet been released. If where the money has gone is not a real problem, if the money is not too much but probably not enough if the problem of "capital idleness" does not exist, it is not reasonable to expect the money that does not exist to flow into the financial markets, especially risky assets.

Fifth, with the economy facing downward pressure, the scale of social financing to support reasonable economic growth may be much higher than imagined. Currently, the endogenous momentum of China's economic recovery is still not strong, requiring the public sector to continue to strengthen spending efforts. If there is still a persistent demand gap in the private sector, the situation of rising social financing scale in the last 3 years may continue. In this case, the policy orientation of "matching the growth rate of social financing and the growth rate of nominal GDP" may imply the need to increase the floating space for the basic match.

Appendix:

The use of funds by LGFVs (local government financing vehicles) is mainly reflected in three aspects. One is to repay the interest on existing debt by borrowing new debt. The second is to provide financing for infrastructure investment. The third is to provide financing for local governments based on the land market.

The new debt to pay interest on the existing debt is about 3.2 trillion RMB. According to data disclosed by Wind, the total interest-bearing debt of China's LGFVs in 2021 was about $58.9 trillion RMB. More than half of this debt was formed in the past five years. If we use the average interest rate of general loans from 2017-2011 as an estimate of the cost of debt, the expenditure on paying interest on the existing debt in 2022 was 320.65 billion RMB. In fact, this is a conservative estimate, as a large number of LGFVs do not have publicly disclosed data on interest-bearing liabilities.

Financing support for infrastructure investment is about 8.8 trillion RMB. The sources of funding for infrastructure investment can be divided into three main parts, budgetary funds, private investment, and LGFVs’ funds. This, in fact, assumes that LGFVs do not use their own funds in infrastructure investment. The assumption may seem a bit strict, but in reality, LGFVs are facing huge cash flow strain, which means they have almost no funds available for new infrastructure investment. LGFVs’ funds include loans, LGFV bonds, etc. Based on the data from the Bureau of Statistics, we project that the total investment in infrastructure in China in 2022 was close to 16 trillion RMB, of which the portion from budgetary funds and private investment accounted for about 45% of the total investment, and LGFV funds about 8.8 trillion RMB.

The scale of funds provided by LGFVs to local governments through the land market is about 3.6 trillion RMB. In 2022, China's real estate sector was facing severe downward pressure, and real estate companies have significantly reduced their land purchase expenditures, posing great challenges to local governments in terms of land purchase. Under this situation, LGFVs began to participate extensively in the land market and became the main force in land purchase. According to the statistics of Liu Yu team of GF Securities, the total amount of revenue from land sales with details disclosed in 2022 was 5.55 trillion RMB, of which the revenue from LGFVs was about 3 trillion RMB, accounting for 54%. In 2022, among the revenue of funds managed by local governments, the revenue from land sales was 6.68 trillion, indicating that the statistics cover the vast majority of land transactions. According to the ratio, it can be seen that LGFVs in the land market provided about $3.6 trillion financing for local governments. Since LGFVs themselves are extremely short of cash flow, the reality is that the funds for LGFVs to participate in land auctions are mainly loans obtained by pledging the existing land funds to banks. This is how the LGFVs provide financing directly to local governments through the land market, which actually achieves the dual goals of stabilizing land values and providing financing to local governments at the same time.

We can also roughly estimate the scale of social financing created by the private sector to verify the reasonableness of this measurement in terms of magnitude. In 2022, new household loans reached 3,829.6 billion RMB, new industrial medium- and long-term loans 3,610 billion RMB, new non-LGFVs 959.7 billion RMB, and equity financing 1,175.7 billion RMB, totaling 9,575 billion RMB and accounting for 30% of the scale of new social financing.