Abstract: The development of the digital economy does not automatically produce a "trickle-down effect" of sharing benefits; only with full integration and connection can it improve the productivity of various industries. At the same time, corresponding institutional arrangements in primary distribution, redistribution, and third distribution can create more and higher-quality jobs, increase residents’ income, improve income distribution, and play a good role in promoting common prosperity through the digital economy.

The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China emphasized the need to accelerate the development of the digital economy, promote the deep integration of the digital economy and the real economy, and build an industry cluster with international competitiveness. This is not only a major deployment of the CPC Central Committee but also reveals the essence and content of the development of the digital economy. From this, we can understand that the development of the digital economy is not isolated; the key is to break the myth of "trickle-down economics" and to promote deep integration with the real economy and other industries. It is also the essence of sustainable, healthy, and inclusive development.

Experience and lessons at home and abroad have shown that the digital economy is the orientation of industrial development under the conditions of the new technological revolution and also the engine for upgrading and optimizing the industrial structure. However, it is also a double-edged sword. Without the characteristic of sharing, it may even widen the gap between capital rewards and labor rewards. If we can’t grasp the goal of development, in other words, if we can’t achieve the development of the digital economy by integrating it with the real economy and connecting it with related industries, the results will be the investment without return, the capability without function, the industry without integration, and the factors of production without market.

This article aims to reveal that the development of the digital economy does not automatically produce a "trickle-down effect" of sharing benefits; only with full integration and connection can it improve the productivity of various industries. At the same time, we will also point out that corresponding institutional arrangements in the fields of primary distribution, redistribution, and third distribution can create more and higher-quality jobs, increase residents’ income, improve income distribution, and play a good role in promoting common prosperity through the digital economy.

There is no "trickle-down effect" in the digital economy

The tenth meeting of the CPC Central Commission for Financial and Economic emphasized that we must adhere to the people-centered development philosophy, promoting common prosperity while pursuing high-quality development and correctly handling the relationship between efficiency and fairness. This requirement also serves as a guideline for the healthy development of the digital economy. In essence, the digital economy is the carrier rather than the purpose, and the digital transformation of the economy is a process rather than an end goal. The development of the digital economy, which is a means of increasing and sharing productivity, aims to promote common prosperity through high-quality development. Establishing such functional positioning reflecting the new development concepts guarantees the sustainable and sound development of the digital economy. Thus the digital economy can make due contributions in building the basic institutional arrangements for the coordination and matching of primary distribution, redistribution, and third distribution.

Both theory and practice suggest that primary distribution is the basic field that determines the improvement and sharing of productivity. The rational allocation of factors of production and the rational incentives for the owners of factors of production are produced in the field of primary distribution. Sharing the benefits of productivity requires the improvement of productivity as a prerequisite. The incentive and efficiency functions in the field of primary distribution are designed to ensure the survival of the fittest in the competition of market players, and thus they are the key to improving productivity. In high-quality development, industrial digitalization centered on the application of computers, the Internet, and artificial intelligence technology not only creates new industries, new forms, and new models at a rapid pace, but also provides a driving force of productivity for upgrading all traditional industries. At the same time, productivity features the allocation efficiency of resources, and the basic way to improve productivity is the continuous reallocation of production factors. The digital economy can just take advantage of its most prominent feature, its connectivity, to promote the continuous extension of the industrial chain and the continuous expansion of the resource allocation space and the continuous improvement of productivity. Primary distribution is also a key field for sharing the benefits of productivity, but the emergence of this function is not natural. No market mechanism can automatically solve the trickle-down economics of income distribution , and there is also no “big trade-off” between efficiency and fairness. Studies have shown that the differences in the income gap between countries not only depend on the degree of redistribution, but also the differences in policy orientation and institutional arrangements in the field of primary distribution . Whether or not the development of the digital economy can promote productivity sharing is not a natural result of industrial development, nor can we redistribute on its basis. Therefore, in order to enable the digital economy to fully play its role in productivity sharing and to achieve the goals of creating more higher-quality jobs, improving labor wages, and narrowing income gaps, we need to make particular regulations and policies.

The development of the digital economy also depends on relevant institutional arrangements in the field of redistribution. The role of the digital economy in improving productivity comes from the "Schumpeter mechanism," and its function depends on the institutional arrangements in the field of redistribution. According to Schumpeter, innovation is a process in which entrepreneurs recombine production factors in creative destruction with the survival of the fittest . In this process, the pace of productivity improvement is not uniform, and the effect of productivity improvement is even more different. Research by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development shows that there is significant heterogeneity among industries and enterprises in the adoption of digital technology or digital transformation, thus resulting in huge differences in productivity performance .

A major challenge faced in the high-quality development stage is how to make the creative destruction mechanism work in both improving productivity and sharing productivity. This mechanism is: enterprises that successfully improve productivity in digital transformation can expand themselves. At the same time, while those that fail to do so are eliminated, which means that the creative destruction mechanism is at work and overall productivity is improved in this process. If there is concern about technological unemployment and the reluctance to accept the survival of the fittest in competition, it seems to the consideration to protect the interests of workers but will hinder the improvement of productivity due to the rigidity of resource reallocation, and then sharing productivity will be impossible.

Robert M. Solow, the Nobel laureate in economics, once pointed out in a short article that people can see the advent of the computer age everywhere, but the increase in productivity cannot be seen in statistics. This remark reveals a real problem that people have been puzzled over, which is known as the "Solow's productivity paradox" and has aroused widespread discussion. Economists have conducted a lot of research to try to solve this paradox and draw useful conclusions from different perspectives . Obviously, this paradox also applies to digital technologies and the digital economy, i.e., why the improvement of overall productivity remains constrained despite the widespread application of technology.

In trying to solve the "Solow Paradox", that is, why the widespread use of digital information technology fails to increase productivity, some studies have found that both rent-seeking and policy protection create barriers that hinder the entry of new market players and the exit of ineffective companies in competition, which makes it difficult for the creative destruction mechanism to function. For example, the entry and exit rates of U.S. companies have been continuously decreasing since the 1980s, which has significantly reduced the business vitality of the U.S. economy . The stagnation of productivity growth means that the scope for making the cake bigger has reduced, and dividing the cake well becomes impossible, leading to the widening of the income gap in U.S. society. Increasing the intensity of redistribution and establishing a sound social security system that widely covers all residents can better protect workers from the social level, and the protection for workers should not be an excuse to hinder the full functioning of the creative destruction mechanism in digital transformation.

Moreover, in the field of primary distribution, redistribution, and tertiary distribution, the orientation of digital technology development and application can significantly affect the level of productivity sharing. Improving productivity is the main motivation for market players to apply digital technology, and necessary policy guidance and institutional arrangements are conducive to promoting the sharing of productivity. At the same time, besides the active driving force system and formal institutional arrangements for economic development, there is still huge space for the "nudge" to improve the level of productivity sharing in digital economic development.

As it is in an operating environment outside the formal institutional arrangement, the nudge is characterized by non-compulsory, small behavioral consequences and side effects, and it is more reliant on the motivation of the parties to "practice goodwill". In the nudge, the boundary between goodwill and malice is often indistinct. In other words, they are often close to each other. If there is a lack of goodwill motivation in the enterprise management function, a malicious nudge is inevitable. For example, some technology platform companies often maliciously use algorithms to achieve the goal of reducing enterprise costs and increasing their own profits. Some have violated anti-monopoly, anti-unfair competition, or labor contract regulations. And some have only performed in some inconspicuous respects, hovering on the edge of laws and regulations. For example, using "either-or" methods to exclude competitors, infringing on consumer interests through information blocking and distortion, misleading purchase behavior by misusing personal data, creating a digital divide against vulnerable groups, and using unequal labor relations to extend working hours, lower work condition standards, and reduce labor compensation.

Nudges that help increase sharing productivity can be found in all three fields of distribution. Among them, the third distribution, which includes philanthropy, voluntary actions, and social responsibility of enterprises and social organizations, is especially suitable for opening up more contribution channels to help the poor and improve income distribution through nudges. In the process of the development of the digital economy, one of the important contents of coordinated and supporting institutional arrangements in the three distribution fields is to create an institutional environment and social atmosphere through laws and regulations, social norms, public opinion guidance, and social integrity systems, so that various market entities can take their social responsibilities by the goodwill actions in science and technology, management and innovation.

Labor Involution in the Digital Economy Era

The double-edged sword effect of the digital economy is most evident in its impact on the labor market. China is in a period of rapid development of digital technology progress and application and industrial structural changes. The process of this scientific and technological revolution and industrial revolution is characterized by an asymmetry between the destruction of old jobs and the creation of new ones. There is also a mismatch between supply and demand for skilled workers, as those who lose their jobs only sometimes possess the human capital required for the newly created jobs. Given the nature of the digital technology revolution, job creation often outnumbers job destruction due to both the unprecedented speed of change and the severity of the mismatch between skilled worker supply and demand.

This result is firstly reflected in the phenomenon of quitting the labor market because of structural unemployment or long-term employment difficulties faced by underskilled workers. Even if those workers who have lost their jobs find new employment opportunities, they are usually more likely to be trapped in informal employment. There are two types of employment, formal and informal employment. Generally speaking, we can distinguish them according to factors such as formal labor contracts, participation in basic social insurance, stable jobs, reasonable working hours, wages and benefits in line with the social average, etc. In practice, it usually works at the individual level to distinguish their types of employment, but it is difficult to make an overall assessment at the macro level. However, we can derive some experiences from numerous surveys and studies and try to make a rough identification with the help of official urban employment structure data.

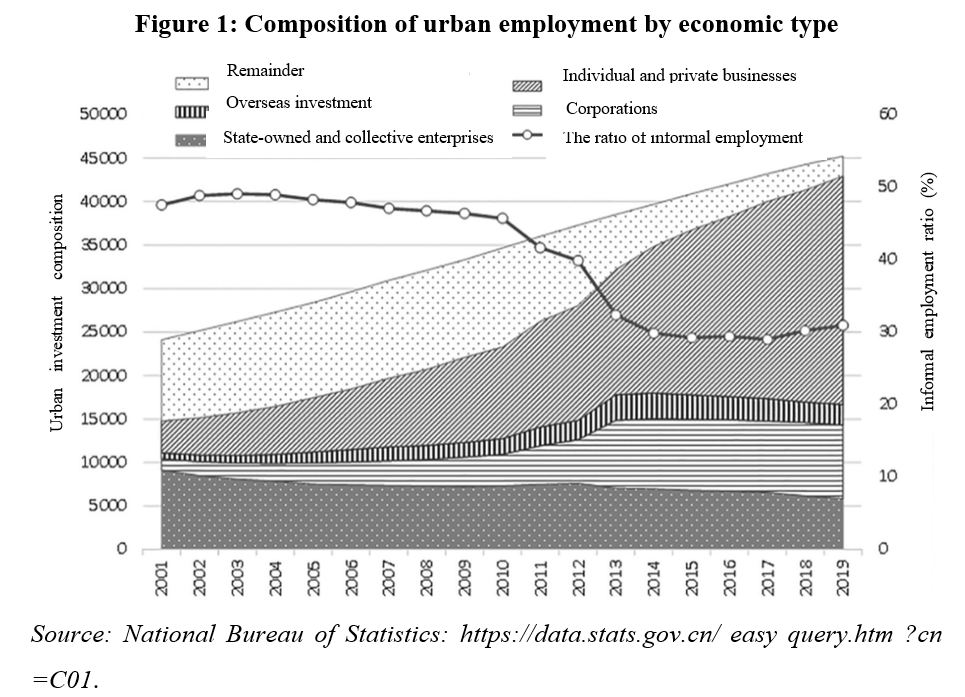

The urban employment data from official statistics come from different statistical systems. From the sample survey data based on households, we can obtain the aggregated number of urban employees. But due to technical reasons such as sample size, we cannot obtain more detailed classified employment data from the same data source. Therefore, to obtain classified employment data, we need to rely on the data aggregated from reporting systems and the survey data from other departments. Specifically, according to the reporting system and relevant department data, urban employment can be classified into state-owned units, urban collective units, shareholding cooperatives, joint venture units, limited liability companies, joint stock companies, private enterprises, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan-funded units, foreign-funded units, and individual urban employment. For simplicity, we merge some types in this classification to form the urban employment structure classified by economic type (Figure 1).

According to the classification mentioned above, there are two components in this statistical data of urban employment, which have typical characteristics of flexible employment and can be roughly regarded as informal employment. The first component is individual employment, including self-employment and personnel employed by individual industrial and commercial households. Obviously, it’s difficult for individual employees to meet the standards of formal employment on almost all employment conditions. In 2019, it accounted for 25.8% of urban employment. The second component is a statistical "remainder". It refers to the difference or remainder between the total number of urban employed persons obtained from household surveys and the sum of employees of various economic types. It roughly reflects the employees who have not been recorded by units or industrial and commercial registration departments. In 2019, it accounted for 5.1% of urban employment. The two components together account for 30.9% of urban employment. The changes in this ratio can reflect several characteristics of informal or flexible employment in cities.

Before the mid-1990s, urban employment, to some extent, still retained some characteristics of a planned economy. The labor market had not yet been fully developed, and neither informal nor flexible employment had a big share, accounting for only 17.2% in 1990. Following the reform of state-owned enterprises to reduce staff and enhance efficiency, flexible employment, as an approach to handling serious unemployment, began to be encouraged, with its share gradually increasing and reaching 49.1% in 2003. At that time, since the labor market system hadn’t been well-established yet, flexible employment was almost equal to informal employment. As the employment situation gradually turned for the better, especially in 2004 when China’s economy passed the “Lewis Turning Point”, the labor shortage became increasingly serious. Moreover, as the working-age population has grown negatively since 2011, the proportion of flexible employment declined significantly and, since 2013, has remained stable at around 30%.

It can be seen that flexible employment emerges as a result of breaking the “iron rice bowl” of the planned economy. Meanwhile, improving the labor market system helps make employment more regulated. As China’s economy experienced the “Lewis Turning Point”, labor legislation and enforcement were strengthened, minimum wages, collective bargaining, labor contracts, and other institutions were rapidly promoted, and the coverage of the basic social insurance system was significantly expanded. All these contributed to stronger employment regulation. In a certain sense, many flexibly employed people have also received better social protection, and thus flexible employment is not completely informal.

In recent years, with the development of the platform economy and the proliferation of new jobs and new forms of employment, many of the new jobs have also taken the form of flexible employment, with some characteristics of informal employment. Accordingly, the share of informal employment no longer declines and even shows signs of a rebound. We certainly should not reject the benefits of flexible employment in creating jobs and welcome new occupations and new forms of employment, but it’s also essential to prevent excessive informal employment and curb its negative effects, which are reflected mainly in two forms, and both can be considered labor force involution.

First, labor allocation shows a tendency against overall productivity growth. Informal employment is often associated with an excessive concentration of labor in low-productivity sectors. Workers who do not have formal employment contracts with enterprises, self-employed ones, or even those employed in unregistered market players are doing low-productivity jobs. Meanwhile, labor productivity is lower in agriculture than in the non-agricultural sector and lower in the general service sector than in manufacturing. In 2021, labor productivity (added value created per employed person) in the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors was 48,700, 207,700, and 170,000, respectively. Therefore, the growth in the number and proportion of informal employment implies an allocation of labor to low-productivity industries.

Second, the increase in incomes of unskilled workers and ordinary households is inhibited. According to data from the 7th Census, in 2020, among all the working-age population aged 15-59, 39.0% received junior school education or less, 24.8% senior school education, and 36.2% higher education. Such human capital endowment of the labor force means that informal employment has high labor supply potential. Such supply-and-demand imbalance and the low productivity nature of informal employment determine that employees’ wage levels and further increases are both suppressed. Meanwhile, informal employees are also significantly less protected than others.

According to international comparative studies, wage equality is an important pillar of social mobility and precisely one of the weaknesses of China’s labor market. For example, with the median of China’s overall labor income as a boundary, those in the bottom half earn only 12.9% of the incomes of those in the top half, and those receiving low wages account for 21.9% of all employed people9. It can be seen that the informal nature of such employment has discouraged wage increase, household income increase, consumption, and thus social mobility.

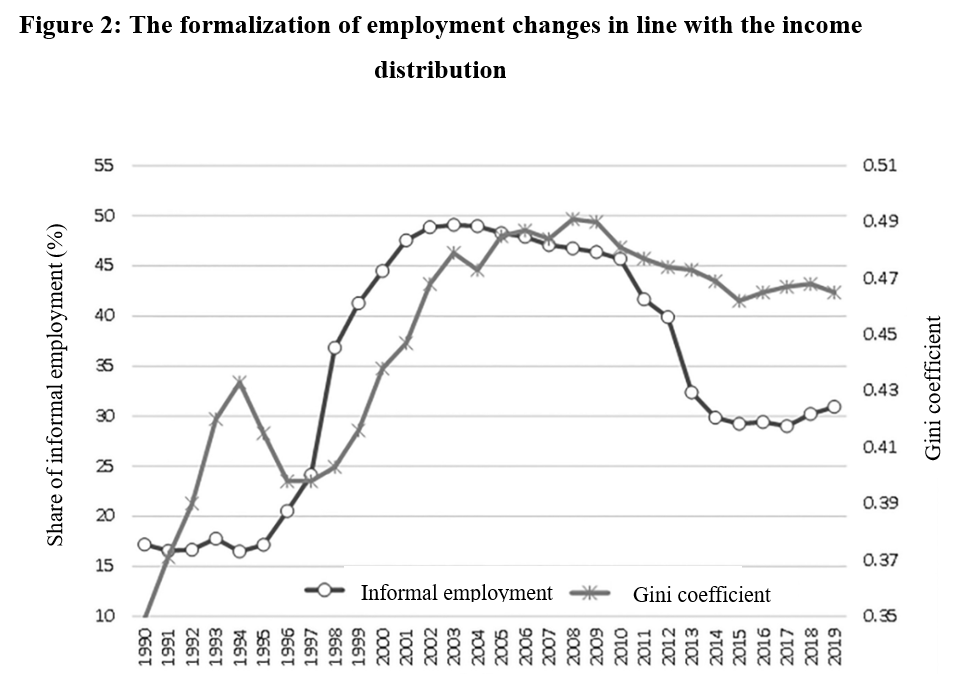

The correlation between informal employment and income distribution can be further observed in statistics. Since the 1990s, the changes in the share of urban informal employment and the Gini coefficient, an important indicator of income disparity, have followed almost the same trajectory (Figure 2). This indicates that the larger the proportion of the informal labor force is, the larger the proportion of the population that fails to earn a decent and reasonable income is, and the less equitable the social distribution of income is. This also suggests that the formalization of employment, or the fact that more workers are employed in areas consistent with their social productivity levels, is an important feature of quality employment and an important way of sharing the outcomes in the development of the digital economy.

Source: Employment data and Gini coefficients for recent years are from the National Bureau of Statistics. For earlier sources of Gini coefficients, see Cai Fang, China’s Economic Growth Prospects: From Demographic Dividend to Reform Dividend, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2016, p.180.

To reduce or mitigate the negative impacts of labor involution on the supply and demand sides requires solutions to many long-standing problems in economic development. Specifically, we should focus and work on the following three aspects.

First, make the technological change, especially the development of the digital economy, a connector rather than a separator between industries and enterprises, and promote convergence of productivity between different types of sectors and enterprises of different sizes, with simultaneous increases across society.

Second, dismantle the remaining institutional barriers and facilitate the flow of labor and other production factors so that workers and their families can share productivity during resource reallocation.

Third, expand the scope and coverage of social protection, social cohesion, and social welfare so that employees in all fields can enjoy equal access to basic public services.

It is important to acknowledge that the development of the digital economy continues to disrupt our perceptions of employment since many new jobs are quite different from the traditional forms of employment that we are familiar with. Many new jobs require more human capital and thus offer higher market returns and adequate social protection. And many are more flexible, in which people face greater challenges regarding job stability, pay levels, and social protection. The social security system does not cover some jobs, such as courier riders, online taxi drivers, script-homicide writers, and e-commerce live-streamers.

This calls for exploring new models of social security coverage in line with the characteristics of new industries and new forms of employment so that flexible employment is no longer synonymous with informal employment, thus achieving increased productivity, productivity sharing, increased social mobility, and better social welfare at the same time.

Addressing the “double-edged sword effect” of the digital economy

The digital economy is a new economic form. Therefore, to address the “double-edged sword effect” that may arise from the development of the digital economy, we cannot simply adopt traditional concepts and follow customary practices. Instead, we should not only ensure the market’s decisive role in resource allocation and make government play a bigger role as a guide and regulator but also promote institutional and mechanism innovation. To be more specific, it is essential to focus on at least the following aspects to develop a correct theoretical and conceptual understanding and apply the understanding to policy formulation and implementation.

Firstly, promote the integration of industries to achieve simultaneous modernization. Modernization has always been a holistic, comprehensive, and simultaneous modernization of all social and economic components. China’s economic modernization is specifically reflected in new industrialization, informatization, urbanization, and agricultural modernization. Among these four aspects, informatization is the pivot connecting all other components. In other words, through data industrialization and industry datafication, the latest technologies from the new technological revolution are applied to various industries, thanks to the development of the digital economy. Therefore, the deep integration of the digital economy with the real economy is the core of the development of the digital economy and the most important manifestation of innovation and development.

Secondly, improve the efficiency of resource allocation to solve the “Solow paradox”. Solow’s description that the computer age was everywhere except for productivity statistics has a more in-depth metaphorical meaning. For example, the development of the digital economy often witnesses a disconnection between the digital technology hardware construction and its effectiveness, which, undoubtedly, is a typical illustration of the causes of the “Solow paradox” and often manifests itself in various ways. It is safe to say that the “Solow effect” is inevitable in any situation where a large amount of money is invested, and physical facilities are constructed, but the capacity is not fully utilized, for example, where a large data center and its computing facilities are built, with no matching demand for computing. Therefore, the development of digital technology still needs to follow the law of “induced technological change,” and the development of the digital economy also needs to follow the law of social demand orientation.

Thirdly, promote and regulate the development of a market for data factors. In the digital age, data has become an increasingly important production factor and naturally requires allocation through market mechanisms. However, this doesn’t mean the data market can be naturally developed and improved. Therefore, not only does the development of the data market need to be carefully nurtured, as in other factor markets, but also the unique laws of data factor markets should be explored, such as special pricing methods, trading rules, flow channels, and allocation mechanisms.

For example, the incremental nature of the digital economy leads to not only the positive effect of promoting productivity gains but also the negative effect of “winner takes all”, in which monopolies and infringements are more likely to arise. Therefore, exploring and forming a management system and governance model that is compatible with the characteristics of the digital economy is not only an important way to break down data barriers and bridge the digital divide but also a key to the co-existence and co-prosperity of the digital economy and the market economy.

Fourthly, promote shared development and innovation for good. The digital economy can be integrated into the real economy ultimately because of its connectivity to various industries and sectors. For digital economic enterprises, especially large digital platform ones, the key to enhancing this connectivity is to pursue market revenue and carry social responsibility, namely, innovation for good.

As estimated by researchers, if both digital industrialization and industrial digitization are taken into consideration, in 2021, China’s broad digital economic volume totaled 45.5 trillion yuan, accounting for 39.8% of GDP10. However, if we look at its due role in driving tax and employment growth, in integrating industries and connecting enterprises, especially in empowering the transformation and upgrading of traditional industries, the digital economy, from the perspective of sharing, is unsymmetrical to its size.

The digital economy is a field governed by the laws of the new technological revolution, such as “Moore’s Law”. With its incredible speed of development and the prospect of almighty applications, the digital economy has created a large number of mega-rich and fast-rich phenomena and has been expected to address global challenges such as an aging population and climate change.

However, reality and expectations are not naturally correlated. Negative and positive effects are both inevitable. In particular, a large and sometimes widening digital divide still exists between industries, sectors, regions, market players, and groups, hindering the sharing of the benefits brought by digital technology. Only through policy adjustments and institutional innovations can we create a pattern of incentive compatibility and ensure that the digital economy is truly shared.

Finally, promote openness and cooperation in the digital economy while ensuring digital security. The 20th CPC National People’s Congress put forward the requirement to develop digital trade, which is a converging point of the development of the digital economy and a high-level opening up. Active participation in international cooperation in the digital economy is an essential requirement for the digital economy to promote opening up and a necessary move to closely connect with the world’s digital information technology and keep China at the forefront of this field. This includes international research cooperation, accession to relevant digital economy cooperation agreements, participation in the formulation of international digital governance rules, and the use of digital technology, especially digital currency, to promote foreign trade, foreign investment, regional cooperation, and the “Belt and Road” construction.

Concluding remarks and policy implications

With the historic alleviation of absolute poverty in rural areas and the achievement of building a moderately prosperous society in 2020, China has entered a new stage of development. The next time-sensitive vision is to persist in advancing common prosperity while high-quality development is ensured and to achieve basic modernization with high quality by 2035. This goal places a higher demand for sharing in the development of the digital economy.

This paper shows that the digital economy is essentially a matter of organic and balanced development of the economy as a whole instead of one as simple as building an industry. Therefore, the market’s allocation of resources, on which China’s economic development is based, and the role of government apply equally to the digital economy. Specifically, the healthy development of the digital economy in line with the new development philosophy needs to be ensured from three levels.

Firstly, China should uphold the people-centered development philosophy and maximize the role of the digital economy development in promoting common prosperity at the institutional level and by updating enterprises’ business philosophies. Secondly, development direction and code of conduct should be regulated by a combination of laws and regulations, industrial policies, and institutional mechanisms. Thirdly, during operation and development, enterprises should be evaluated according to their market performances, screened according to industrial competitiveness, and tested according to productivity and economic efficiency.

For instance, the digital economy creates more quality jobs. While studying the intrinsic relationship between technological progress and employment, we have perhaps overlooked such a regularity: flexible employment is often compared with, and sometimes even confused with, informal employment, so people failed to draw a proper conclusion about the prospects of informal employment.

Specifically, considering the relative scarcity of labor factors and the level of institutional development of the labor market, people were convinced that the in-formalization of employment would follow an inverted U-shaped trajectory, which meant that in-formalization would pass a turning point, which, once crossed, would never occur anymore. Take the 2004 “Lewis turning point” in labor shortages and the 2011 turning point as the working age population began to grow negatively, as examples. Both can be considered turning points after the yearly decline of informal employment.

Flexible employment and informal employment are not necessarily the same. The former is a manifestation of objective necessity, while the latter is determined by institutional arrangements and policy choices. Once the technological nature of the digital economy is taken into account, the trend of flexible employment is likely to change periodically, following a horizontal S-shaped trajectory. Moreover, responding with institution building according to the nature and pattern of changes is the only way to ensure the smooth operation of labor market institutions and social protection mechanisms, which is the foundation of differentiating flexible employment from informal employment. Only by adapting to this trend can the development of the digital economy fulfill its responsibility of ensuring both equality and efficiency.

Whether it’s digital industrialization or industrial digitization, it boils down to the digital transformation of the economy as a whole, which symbolizes that digital technology, with computer and information technology at its core, is permeating into all aspects of the economy and will reach everywhere. This article is far from covering all aspects of the development of the digital economy for the common good, and further research on the digital economy and platform economy is still needed in many fields, such as taxation, debt, finance and financing, anti-monopoly regulation, green development, and promoting rural revitalization and smart city development. The digital economy is on the ascendant in China, and there is no end to the exploration of various fields.

This article was first published in Issue 3, 2023, "Dongyue Tribune." It is translated by CF40 and has not been subject to the review of the author himself. The views expressed herein are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or any other organizations.