Abstract: The downward inflationary trend in the US is well established, and the policy rate is likely to peak at no more than 5%. However, a shift in the Fed’s monetary policy may come later than the market expects. For the Chinese economy, on the one hand, the pressure on capital outflows under China’s capital account is expected to ease; on the other hand, the pressure under China's current account may rise and become one of the main risk points.

Last year, the US economy faced the threat of high inflation, with the CPI at a 40-year high, forcing the Fed to raise interest rates aggressively and begin a second taper.

Between March 2022 and February 2023, the Fed raised interest rates eight times by a total of 450 bps, having a significant impact on the global economy and capital flows.

As we approach 2023, it is worthwhile to investigate the Fed's monetary policy and its impact on the Chinese economy.

Ⅰ. WHERE IS THE US IN THE RATE HIKE CYCLE?

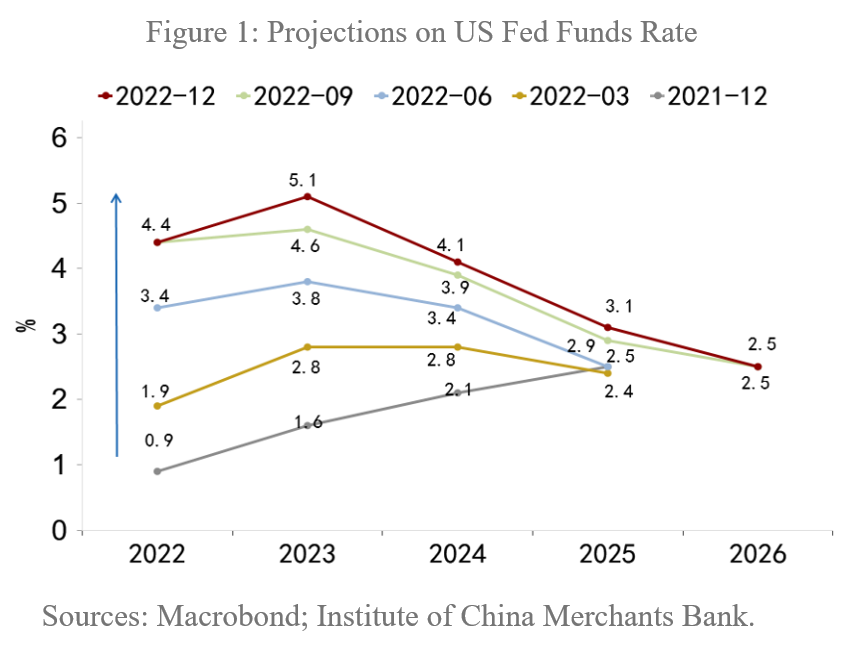

The Fed's monetary policy has a "dual mandate," which includes full employment and price stability. Last year, with the US unemployment rate at an all-time low and inflation all-time high, the policy focused on quelling inflation, and the Fed's rate hikes appeared to be “higher and longer,” with the dot plot shifting upwards. The median policy rate forecast for the end of the year is in the 5.0-5.25% range, up nearly 250 bps from the same period last year.

The question is: Is it possible that the Fed's forecast on policy rates for the end of this year is wrong?

Some argue that the downward trend in US inflation has been established and the prospect of an economic slowdown or even recession is emerging, making it difficult for the Fed's rate hike path to move upwards. With another 25bp hike in H1 2023, the Fed's rate hikes will end, and rate cuts may start in H2 2023.

Another viewpoint is that the US job market remains hot, with new jobs exceeding market expectations and inflation struggling to return to the 2% target, and that the Fed's rate hike curve may continue to rise, with no turning point for a rate cut this year.

My assessment of inflation and the path of Fed rate hikes leans towards the former, but I remain skeptical about whether monetary policy has reached a tipping point.

First, the Fed systematically underestimated the slope and height of inflation's upside early last year, and is likely to repeat that mistake this year but in the opposite direction by underestimating the speed and depth of the inflationary spiral. CPI inflation in the US began to fall sharply in H2, 2022, from 9.1% in June to 6.5% in December. A representative indicator of the rapid decline in core commodity inflation is used car prices.

This year's focus is on whether core service inflation will drive US inflation lower.

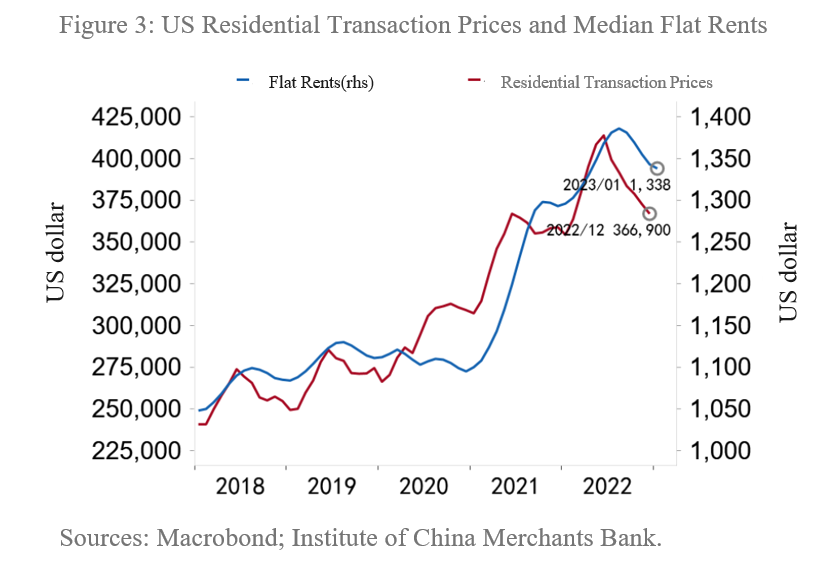

The trend in rents is the most critical price indicator. Rents had lagged behind the movement in house prices. Rents have fallen with house prices since Q4, 2022, and are expected to fall rapidly again in H1, 2023.

As a result, CPI inflation in the US is expected to fall rapidly this year, returning to levels below the policy rate in Q2, when the US real policy rate shifts from negative to positive. If real interest rates rise above 2%, exceeding the highest level since the subprime crisis (1.47%), aggregate demand and economic activity will be further dampened.

The debate is around the hot job market.

With real interest rates rising as a result of lower inflation, economic activity will rapidly cool, labor market performance will weaken, and the Fed's policy objectives will be transformed.

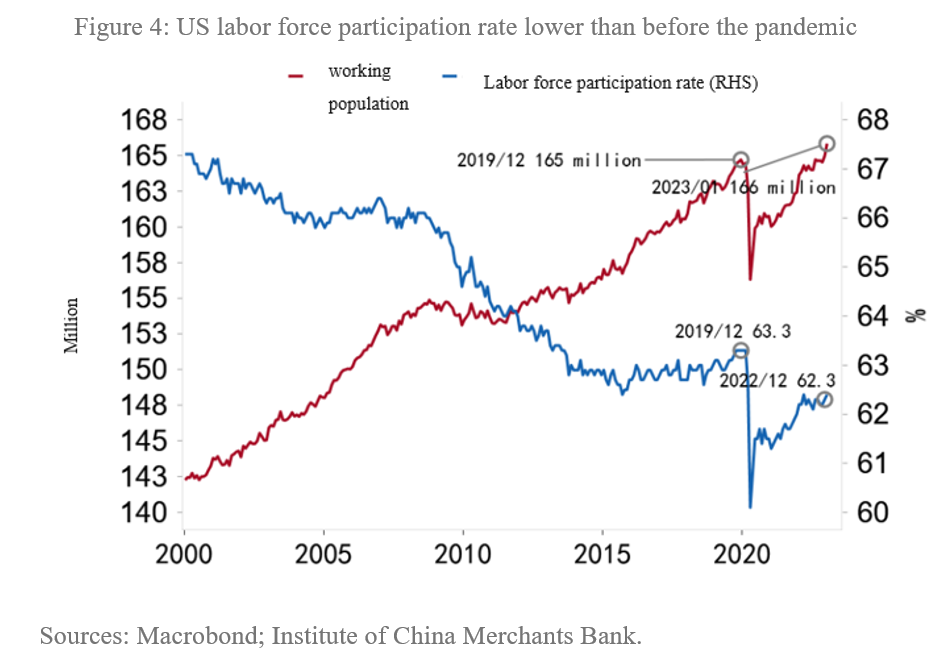

The US non-farm payrolls in January exceeded expectations, with 517,000 new jobs added and the unemployment rate further down to 3.4%. However, the US employment population is still about 5 million below the pre-COVID level, and there are serious structural problems in the labor market.

On the one hand, there is a gap in the labor force participation rate; on the other hand, new employment and payroll growth diverged, with payroll growth falling from a high of 5.9% in March last year to 4.4% and quarter-on-quarter growth slowing from 0.6% to 0.3%, indicating that the risk of a "wage-price" spiral has not yet emerged.

The strong performance of the US labor market is important because it might limit the magnitude of the US economic downturn or recession, meaning that the economic recession in the US this year might be relatively mild.

High job vacancies provide a “buffer” for the labor market and become an endogenous driving force that supports household income and US economic growth. Coupled with massive fiscal stimulus during the Covid-19 pandemic, the excess savings of the US household sector by the end of 2022 still exceeded 1.5 trillion US dollars which are expected to run out in the second half of this year. The balance sheets of the US private sector, especially the household sector, are relatively healthy, with the debt ratios significantly lower than the figures during the subprime mortgage crisis.

To sum up, the downward trend of US inflation has formed, and the policy rate may peak at no more than 5%. However, the Fed might keep a high policy rate for a while, as the downward pressure of the economy is smaller than expected. Unless the economy falls into a real recession, the Fed does not need to pivot to rate cuts. In other words, a shift in the US monetary policy might come later than the market’s expectation.

II. WHAT IT MEANS FOR CHINA’S ECONOMY?

One thing is certain. The Fed’s rate hikes have dampened demand to a large extent. From Q2 to Q4 of 2022, capital spending in the US private sector has contracted sharply for three consecutive quarters.

This January, the US ISM’s Manufacturing PMI plummeted to 47.4, remaining below the threshold of 50 for three months in a row. Over the past two decades, only four times when the US Manufacturing PMI fell below 50, including the dot-com bubble in 2000, the SARS pandemic in 2003, the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, and the early stage of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

In history, the US economic recession has always been accompanied by a cycle of interest rate hikes. Recently, the inverted yield curve and leading indicators like the consumer expectation index in the US have continued to signal recession warnings. The yield curve inversion between 10-year and 2-year Treasuries has exceeded 80bp, the highest level since the 1980s.

With the global economy slowing down or even falling into a recession, the channel through which the Fed’s monetary policy affects China’s economy will shift from capital account to current account.

On the other hand, China’s current account might face much greater pressure, which is one of the major risks to China’s economy.

With the US and European economies heading into recession, external demand will drop sharply, weighing on China’s export growth. The IMF estimated that global economic growth would slow down from 3.4% in 2022 to 2.9% in 2023, and global trade growth in goods and services will decline from 5.4% in 2022 to 2.4% in 2023. While external demand is contracting, the global supply capacity is recovering rapidly, which will undermine China’s exports from both the supply and demand sides.

In addition, reshoring industries away from China and the “China Plus One” strategy adopted by multinationals to find alternative production sites might replace some of China’s production and exports. Recently, the escalating China-US technology “decoupling” might add to the headwind of de-globalization and undermine China’s high-tech exports.

With the decline of exports and increasing import demand due to the reopening, China’s trade surplus in goods will decrease; meanwhile, the normalization of international travel will expand the trade deficit in services. Given the impacts of these multiple factors, the surplus in China’s current account might decrease sharply, weakening the support for economic growth.

As external demand falls, China’s economy should shift its growth engine and rely more on internal market. Whether China can hit a growth target of more than 5.5% depends on the momentum of internal demand, which is another issue.