Abstract: Today’s global monetary system, under sluggish growth, diminishing policy effect, and unanchored inflation expectation, needs to be re-anchored. Such re-anchoring should be more strategic and forward-looking beyond the narrow scope of the exchange rate. If well-engineered, a new anchor could promote a self-circulating stabilizing mechanism for the global monetary system. Commodities should not and cannot be such a new anchor. Instead, an ideal new anchor should be based on technological advances, industrial progress, hedge against inflation, capital flow, floating exchange rate, and currency equity.

The title of my speech today is “Global Financial System: Crises, Change, and The Way Out”. I authored a book in 2019, Global Financial System: Crises and Change. And now I would like to share some of my updated views given the recent changes in the global landscape.

I will touch upon several things: 1) challenges facing the current global monetary system; 2) the necessity and urgency of anchoring the system again today; 3) the importance of more in-depth and forward-looking thinking to the re-anchoring.

I. CHALLENGES FACING TODAY’S GLOBAL MONETARY SYSTEM

Today’s global monetary system is usually referred to as the “Bretton Woods System 2.0.”

The Bretton Woods System is the global monetary system established in 1944-1945 when World War II was nearing its end, led by the United States and participated by a total of 44 countries including China. It decided to 1) peg the US dollar to gold, and all other currencies to the USD; 2) restrict capital glow; and 3) restrict exchange rate adjustments. The System began to collapse in 1971 and was declared void by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1973. The world began to look for its replacement since then.

The system that followed featured a floating exchange rate regime, encouraged capital flow, and pegged no currency to gold. After a painful search for a new anchor, several major exchange rate adjustments, and the signing of the Plaza Accord (1985) and the Louvre Accord (1987), the Bretton Woods System 2.0 finally took shape in 1987 and has been playing a major role driving globalization and world economic growth ever since.

Before 1944-1945, the gold standard or the precious metal standard (silver or bronze in China, for example) prevailed for over 1,000 years. The System in 1944-45 was a transition, pegging the USD to gold, and it was the new system built in 1987 that was a brand-new one decoupled from gold.

That said, the Bretton Woods System 2.0 has been facing many challenges since its inception, especially the 2008 global financial crisis which triggered a renewed exploration of a new anchor. And the exploration is still going on 14 years after the GFC.

After the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020, the U.S. introduced massive monetary easing and fiscal spending programs that pushed up its annualized year-on-year M2 growth to over 20% and its fiscal deficit to a whopping 6 trillion USD, 30% of total GDP, during the 12 months from April 2020 to April 2021. The enormous stimulus heated the country’s inflation which hit 8.5% in April this year, spilling over to the global monetary system as well, followed by new blows from the Ukraine crisis under which part of the Russian central bank’s USD reserve was frozen and some of the Russian financial institutions were removed from the SWIFT system.

To address these new headwinds, some proposed building the 3.0 version of the Bretton Woods System based on more underlying sources of credit such as gold and natural resources. The most representative of them is Zoltan Pozsar, who believes that the huge commodity price volatilities as a result of the Ukraine crisis have led to a surge in the price of non-Russian commodities and a plunge in the price of Russian ones. The plunge was partly because Russian commodities were traded in rubles which slid by 40 percentage points in a very short time after the crisis broke out, though picking up later. This means that the world now has two commodity prices: one for non-Russian commodities, and the other for Russian commodities.

From an arbitrage point of view, he thinks China has much to gain from this, especially for Renminbi internationalization. He also believed that the U.S. and European countries might take huge blows from the crisis, making the USD more vulnerable. But market statistics have proven that prediction untenable: the USD has risen significantly against the euro, the Japanese yen has been slumping, and currencies of some of the emerging market economies as well as RMB have all come under greater depreciation pressure.

Pozsar’s analytical framework is defective, and his conclusions are debatable.

We hold that commodities should not and cannot be a new anchor for the global monetary system.

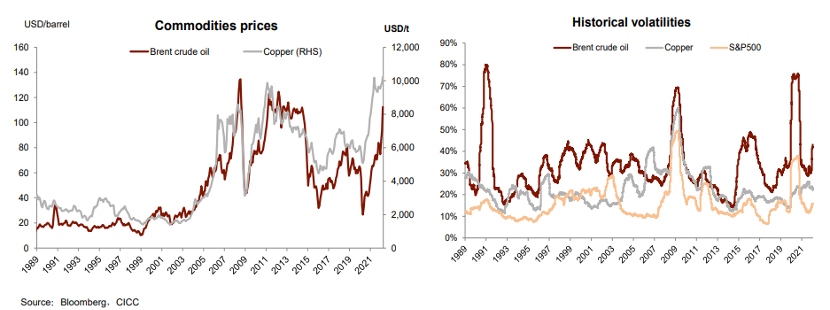

First, commodity prices are highly volatile, and the short-term volatilities are determined by the supply-demand balance and the level of inventory. However, an anchor is supposed to provide stability. Anchoring the global monetary system to highly volatile commodities would be counterproductive, increasing market concern over even more unstable inflation expectations.

Second, commodity resources are unevenly distributed. Crude oil mainly comes from the Middle East and Russia; precious metal and nonferrous metal mainly come from South America, Russia, and Australia. As a result, their supply could be easily manipulated, adding to price volatility.

More importantly, we argue against making commodities the new anchor for the global monetary system from a sovereign currency point of view. Currency issued by a state is part of the equity in the national capital structure. A country has to engage in sufficient equity financing at the state level to sustain economic growth, and its currency is an important part of that, as are its government bonds denominated by its local currency. The invention of paper money enabled the state to conduct more equity financing at the state level, which was also necessary. It makes no sense to delegate the power of equity financing of such importance to commodities or gold.

All global monetary systems before 1971 were pegged to gold or disguisedly so. It was until 1987 that fiat currency began to prevail, with an unprecedented impact on human society. This can be said a major transformation unseen in almost 1,000 years. We have just started to feel this transformation, and it just makes no sense whatsoever to go back to the old system a thousand years ago now.

Before sovereign currency was put into use, there was no equity in the national capital structure. All were debts, because how much money a country could issue depended on how much gold it had, and money holders had the right to exchange their money for gold. We would be going back to a disguised gold standard system if we peg our currencies to commodities. Since the central bank is not capable of directly controlling the output of related commodities, equity financing and the monetary system at the state level would be dragged back to the gold standard era.

At the macro level, whether we go back to the gold standard that prevailed before the Great Depression in the 1930s or we implement a new system based on a basket of commodities, it would all be too costly and risky if money issuance is realized by adding debts at the state level again. This will hinder economic growth and technological development, representing a major step back in human history.

At the micro level, anchoring the monetary system to commodities means anchoring our future to the traditional resource industry to which more capital will flow. This will undo the industrial revolution, and impede technological advancement, especially digitalization and decarbonization.

II. RE-ANCHORING THE GLOBAL MONETARY SYSTEM: NECESSITY AND URGENCY

The global monetary system needs to be re-anchored. Why is that necessary and urgent? We began to think about the question back in 2008 amid the GFC. Today’s monetary system suffers from sluggish growth, diminishing policy effects, and de-anchored inflation expectations, among other problems. The 2020 Covid outbreak has led some countries to go extreme on monetary policy without considering the externalities of their acts. Monetary policy has even been weaponized by some after the Ukraine crisis broke out, triggering further discussion of the global monetary system among scholars, policymakers, and market participants alike.

First, sluggish global growth. The IMF tuned down its forecasts of global GDP growth systematically in its annual spring meeting this April. The world economy has been bogged down ever since the 2008 GFC, which was followed by the European debt crisis in 2012 and emerging market economy crises in 2015, 2018, and 2019. The Covid-19 pandemic dealt profound and sweeping blows to the world economy, with no country immune. China was the only major economy with positive growth in 2020. All others have suffered hugely.

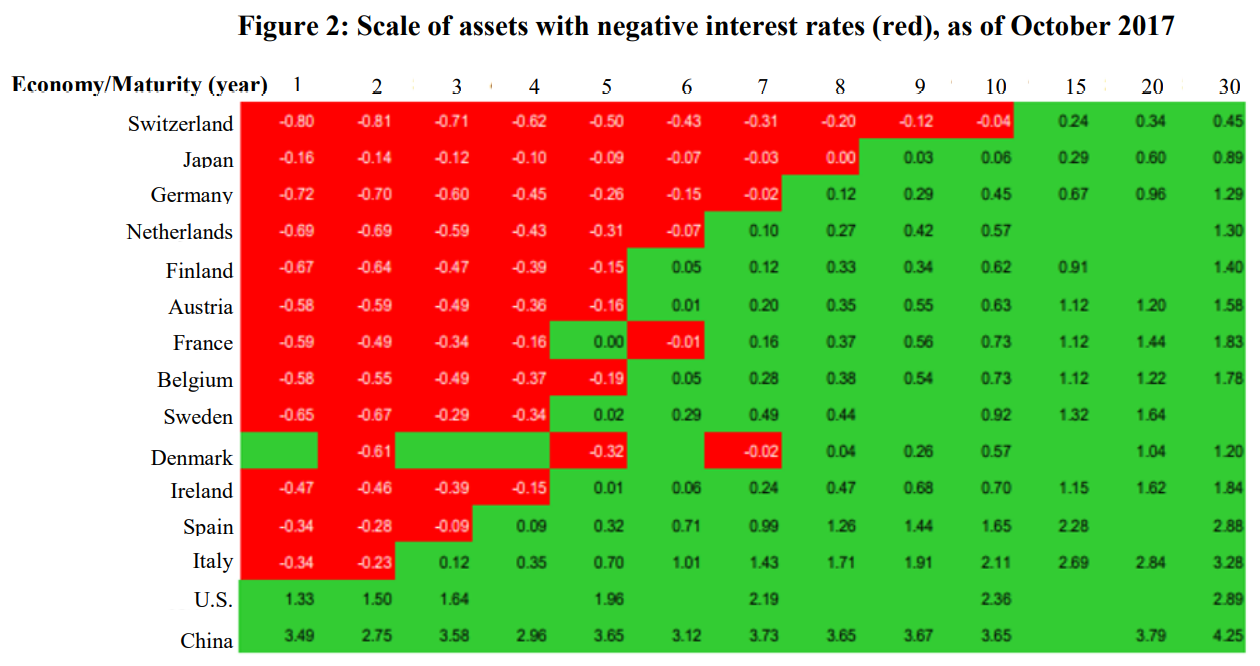

Second, diminishing policy effects. Quantitative easing, fiscal policy, and other measures implemented since 2008 have played a positive role in stabilizing the capital market and the economy, but having been used repeatedly, their marginal effect has been decreasing. Before 2019-2020, many of the countries had negative interest rates, indicating a minor role of monetary policy. The figure below shows the scale of negative interest rate assets as of October 2017. We can see that many countries had negative interest rates for their assets with various maturities from one to ten years. Therefore, the previous monetary policy was hard to sustain, and we must find a new anchor or a new policy combination.

Third, difficulties in anchoring inflation expectations. This involves two aspects: 1) the interest rate was deep in the negative territory before 2019 which was very detrimental: inflation had to stay within a reasonable range such as 2.5% which was the target of some of the countries, but negative or zero interest rates corresponded to a CPI at zero or negative which was bad for economic growth, with monetary policy tools ineffective and banks suffering from big blows. 2) It’s all bad if inflation rises too fast, is too low, or is too high. Starting from last May, our problem has been that inflation has been rising too rapidly. The U.S. now is having a CPI of over 8% which is very disturbing.

III. RE-ANCHORING THE GLOBAL MONETARY SYSTEM REQUIRES LONG-TERM AND FOUNDATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Discussions on finding a new anchor for the global monetary system have largely been within the scope of currency exchange rates, including the competition between the US dollar and other currencies such as the euro, enhancement of emerging countries’ currencies such as the RMB, and reform of IMF’s SDR mechanism, all beneficial suggestions and explorations, but there are deeper issues that worth probing into.

To discover a new anchor, we must seek further, higher, and outside the realm of exchange rates. There should be two important principles:

Principle1: Only by understanding the essence of the global currency anchor can we find a theoretical solution. The anchor should have two essential functions: to stabilize long-term inflation expectations and to support and guide human society toward long-term sustainable development.

Principle 2: Only by making good use of the global currency anchor can we find a practical solution. If designed correctly, an anchor can promote a self-circulating stability mechanism for the global currency system, so it must be able to hedge the inflation for the long run, and that is why bulk raw materials and gold are not good choices, as they are pro-cyclical and catalyst for inflation.

The new anchor must be based on technological innovation and industrial revolution that feature digitalization and low carbonization, which bring deflation because of Moore's Law.

Moore's Law is the observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit will double about every 18 months, but the price fall in half. It is a valid law in terms of computers. If technological innovation is deflationary, why not make good use of it in the design of the new anchor? Only with technological innovation can long-term inflation be hedged and stabilized.

Electronic products are getting a bigger share compared with food and beverage, and if the quality of consumption is taken into account, there will be a significant deflation with social advancement, which is precisely the indicator of the progress of human society. We should make good use of these deflationary forces to hedge inflation and achieve a self-negative feedback mechanism.

The sustainable development of the future society depends on technological innovation, especially in digitization and low carbonization. Digitalization is the most important area of technological innovation and has brought and will continue to bring great changes to all aspects of modern society.

Meanwhile, energy still plays an extremely important role in human society. Climate change is indeed one of the greatest global challenges of our time. Therefore, low-carbon green energy technologies will have a place in the monetary system we envision. This is fundamentally different, if not the opposite, of the proposal to build the system on conventional energy sources.

In addition, the technologies of bio-medicine, nuclear energy, aerospace, new material, and agriculture are also closely related to the development direction of human beings, and can also occupy a place in the new system.

Anchoring to commodities would be a step backward. It would drive human society to the old path of innovation inhibition, the Malthus Trap, and tackle inflation with war, famine, and plague. Malthus stated that the population increased in a geometric progression while food production increased in an arithmetic progression. Thus population grew faster than food production and tended to outstrip it in a short time. Inflation can be fought through war, famine, or plague, but it will be extremely tragic.

When global stagflation occurred in 1970, the Club of Rome, a prominent think tank, released a report on the limit of growth, or the 1970s version of Malthusian theory. Many of the recommendations are absurd and the judgments on economic growth and energy prices are wrong because they did not give full consideration to technological innovation. The progress of human society is the process of breaking the Malthusian trap.

The process of anchoring global currency, we believe, should be as follows:

Anchor 1: USD dominance, USD pegs with gold, the establishment of Bretton Woods system, capital control, fixed exchange rate, and fixed currency.

Anchor 2: USD dominance, multiple currencies without gold, weakening of the system, capital flows, floating exchange rate, currency changes. This is Bretton Woods system 2.0.

Anchor 3: technological innovation, industrial progress, inflation hedging, capital flow, floating exchange rate, and currency equity.

Currency evolved from fixed currency to variable currency to equity currency. Equity currency is a theory put forward in the national capital structure and has been commended by the Sun Yefang Economic Science Foundation. The amount of currency to be issued should be designed in accordance with a country’s equity and its capital structure to provide sufficient financing for national development. The issuance could be increased if there are good enough investment projects, but not too much. If there are no good investment projects and no financing needs, there will be problems with additional currency. Of course, equity currency includes currency and government bonds denominated in local currency.

The market advocated the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) in around 2020. Its kernel error is to believe that government bonds are the assets of residents or enterprises, and the more assets, the better. From the perspective of national equity, when the newly financed projects underperform, the original equity will be diluted, and the stock price will fall, corresponding to inflation. The USD is facing huge dilution costs, a huge challenge facing the world today.

Some of the contents mentioned above are quoted from my book Global Financial System: Crisis and Change, if you are interested.

This is the speech made by the author on May 11, 2022, at the 391st Chang’an Lecture hosted by the Economists 50 Forum. The views expressed herewith are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or any other organization. It is translated by CF40 and has not been subject to the review of the author himself.