Abstract: At present, it seems difficult to identify where the Chinese economy stands in the business cycle by the performance of individual indicators. The author approaches the subject by looking at the inventory cycle of the manufacturing industry, or specifically, two indicators—manufacturing PMI inventory of finished goods and raw materials. The results show that China's manufacturing industry is at the stage of passive restocking, where the inventory of finished goods is growing and that of raw materials is declining. In the short run of the inventory cycle, China's economy may face the pressure of active destocking, that is, while the inventory of raw materials continues to decline, the backlogged finished goods inventory may also decline as companies delay production and run down stocks. When that happens, the macro-control policy will be affected by inventory adjustment, and economic recovery will also slow down. It’s crucial to put policy in place to guide business expectations. The right policies could allow companies to move straight to passive destocking without having to undergo a period of active destocking, thereby eliminating the constraints on economic recovery.

Ⅰ. THE STATE OF CHINA'S ECONOMY

It appears to be challenging to determine the present position of the Chinese economy based on main economic indicators. From the perspective of GDP growth, this year's economic growth may not be as strong as the market anticipated at the beginning of the year under the influence of unexpected factors at home and abroad. From the perspective of price, however, the year-on-year growth rates of CPI and PPI as of August 2022 were 2.5% and 2.3%, respectively, well within the reasonable range, and the output gap appears to be fairly acceptable. But it should also be noted that moderate inflation could be a symptom of supply-side shocks, and the lack of aggregate demand may not be as mild as it appears.

Again, however, the labor market did not exhibit obvious signs of a supply shock. It seems to be returning to normal when you consider the unemployment rate. The surveyed urban unemployment rate reached the highest point of the year (6.1%) in April, and then fell back to 5.3% in August. Although the unemployment rate for youth aged 16 to 24 is at an all-time high, overall employment still appears to be within the normal range, with the unemployment rate of 5.3% at a low level since 2020, even the same as the rates in February and July 2019.

In this vein, the supply side (at least in terms of the labor market) does not appear to have been severely hit. Commodity prices have also started to level off after a sharp rise. Under these conditions, it seems fair to say that China's current output gap is within desirable bounds. However, it is challenging to draw this conclusion, as for instance, it might still be necessary to increase the coverage for the urban unemployment rate survey. In short, we need to look at the state of the economy from more angles so as to provide a more accurate depiction.

II. FOUR STAGES OF THE MANUFACTURING INVENTORY CYCLE

We can group the changes in two types of manufacturing inventory—raw materials and finished goods—into four different stages of the inventory cycle: passive destocking, active restocking, passive restocking and active destocking.

The first stage, passive destocking, refers to a situation in which demand begins to improve and production gradually resumes. As the increase in demand is quicker than the resumption of production, the current demand surpasses the current production, so that the inventory of finished goods continues to decline, but that of raw materials has begun to increase.

The second stage, active restocking occurs when demand is strong, expectations are growing optimistic, and production is expanding at an accelerated rate, so that current production is greater than current demand, leading to a rise in finished goods inventory. At the same time, raw material inventory is increasing in order to meet rising production.

The third stage, passive restocking occurs where both demand and production start to slow down, but current production is still greater than current demand, leading to a rise in finished goods inventory. At the same time, raw material inventory begins to fall.

The fourth stage, active destocking happens when demand continues to decline, expectations turn pessimistic, so that production starts to contract, and finished goods inventory falls. The inventory of raw materials also falls further.

III. OBSERVING ECONOMIC CYCLES WITH PMI INVENTORY INDICATOR

First, why forego industrial finished goods inventory as an indicator? (1) Industrial finished goods inventory is measured in money value, which makes it a nominal term. While PMI is based on subjective data gathered from surveys, its inventory indicator reflects the actual inventory level, and therefore requires no correction for price changes to reduce error. (2) There are problems with the data of industrial finished goods inventory, such as missing data, change in measuring standards, and lag in the release of data. (3) Industrial finished goods inventory does not distinguish between raw materials and finished goods, while the manufacturing PMI does. (4) Manufacturing inventories account for the vast majority of industrial finished goods inventories (95% in 2015), so manufacturing PMI is representative enough. (5) It is not difficult to derive year-on-year changes from monthly manufacturing PMI data.

Second, when the PMI data is used, the neutral value of 50 may be adjusted according to the actual situation. In particular, the PMI inventory indicator in many countries has been below 50. But this does not mean destocking in the sense of an economic cycle. Instead, it mainly reflects the trend of technological progress in the inventory management, such as the improvement of supply chain management, the development of logistics industry and transportation infrastructure, etc. We propose four scenarios to describe the different types of technological advancement in inventory management.

(1) No technological advancement in inventory management. In this scenario, the neutral value of PMI inventory index stands at 50, and the feedback from the interviewed companies on inventory increase and decrease directly corresponds to inventory restocking and destocking.

(2) Technological advancement stays constant. In this scenario, the neutral value of the PMI inventory index will be a constant value below 50. The increase or decrease in inventory reported by the interviewed companies will have to be compared with this constant value before we can determine whether there is inventory restocking or destocking. In this case, we use historical average as the neutral value and the deviation as the fluctuating component.

(3) There is a stable change of rate in the advancement of inventory management technologies. In this scenario, the neutral values of the PMI inventory index will form a straight line with a positive or negative slope. A positive slope indicates a gradual slowdown or even a regression of technological development (in effect the latter case would not occur); a negative slope means an accelerating rate of technological progress. In this case, we perform a linear regression of the time trend using all the historical data and regard the fitted value at each time point as the trend value and the deviation as the fluctuating component.

(4) The rate of technological advancement is not a constant, nor is its second-order derivative. In this scenario, the neutral value of the PMI inventory index is in a state of flux with no stable pattern. We could only observe the trend in retrospect and determine the neutral value at each point according to its trend line. In this case, we use the trend value obtained from the HP filter as the neutral value and the deviation as the fluctuating component.

Again, when using the PMI inventory index to observe the economic cycle, the index should be annualized. As PMI is a survey of economic performance through which the surveyed companies compare the current month with the month before, the index indicates a month-on-month change. However, month-on-month change is more volatile, sometimes due to seasonal factors, which can be removed by seasonal adjustment, and sometimes non-seasonal reasons, such as the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, and the resurgence of the pandemic in the Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, and northeastern China in the second quarter of 2022. These non-seasonal factors cannot be excluded by seasonal adjustment and will add to the volatility. For example, the finished goods inventory and raw materials inventory in March 2020 both posted a sharp month-on-month increase. But this is only a normal post-pandemic recovery, and should not be regarded as the beginning of active restocking and thus the boom cycle of the economy. Therefore, we observe the inventory cycle after annualizing the PMI inventory index.

IV. CHINA’S ECONOMY IS IN THE STAGE OF PASSIVE RESTOCKING.

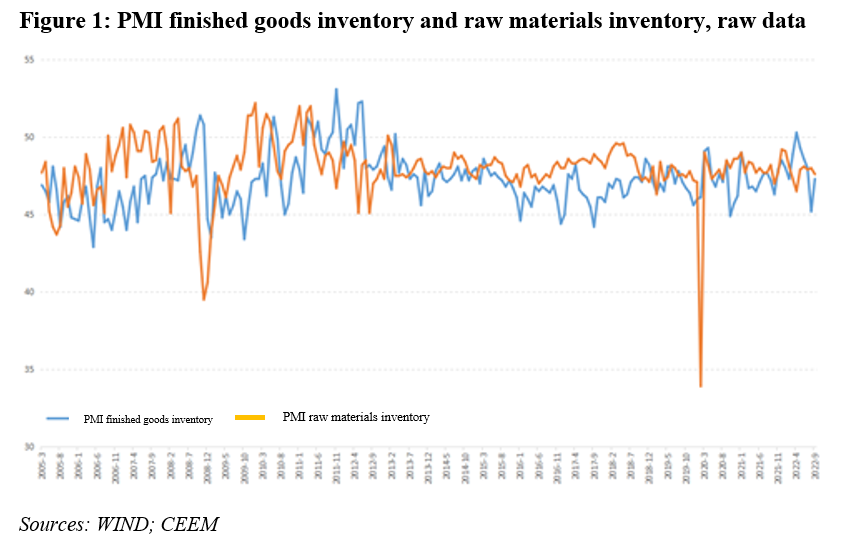

First, we can see that since January 2005 when data were available, the raw data of finished goods inventory and raw materials inventory have fluctuated a lot and remained below 50. It is thus difficult to have a clear picture of the inventory cycle simply through direct observation.

Second, we adjusted the PMI finished goods inventory and raw materials inventory based on the abovementioned four scenarios in order to determine the neutral value. The results show that the second scenario (the rate of technological progress as a constant) yields more favorable results and is the closest to and most correlated with the historical cycle of economic growth on a year-on-year basis. Therefore, the subsequent analysis will employ the results based on the assumption that the rate of technological advancement is a constant.

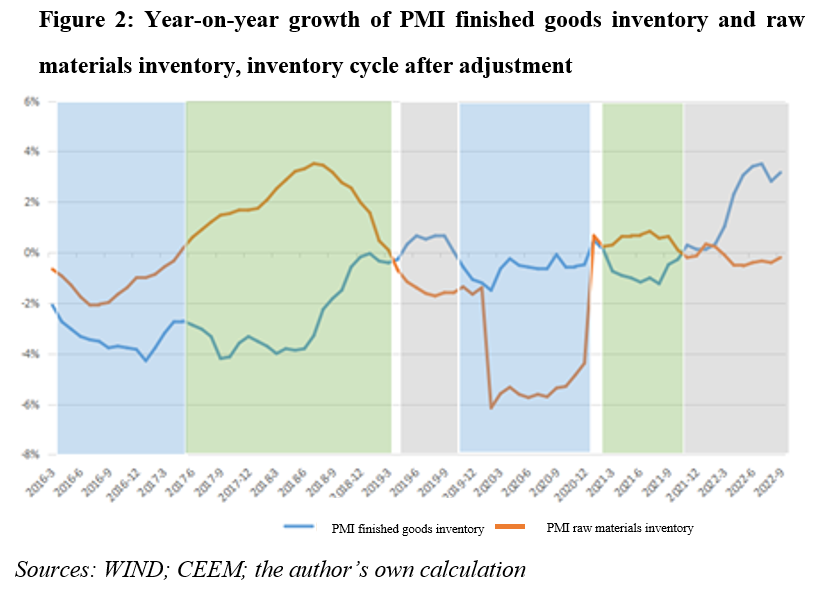

Third, under the assumption of a constant technological progress, we use historical average as the neutral value of PMI finished goods inventory and raw materials inventory, and convert the month-on-month changes of both indicators into annualized figures. The results are shown in Figure 2:

Since the onset of the supply-side structural reform in early 2016, the inventory of finished goods and raw materials both decreased, marking the start of active destocking. In 1H17, raw materials began to pile up amid rising expectation for higher price, while the inventory of finished goods remained on a downward track entering the passive destocking phase. During mid- and late-2019, manufacturers entered a new stage where their inventory of finished goods increased passively while that of raw materials fell.

After COVID broke out in early 2020, Chinese manufacturers turned to destock proactively with the inventory of both finished goods and raw materials decreasing until the end of the year. For the best part of 2021, they were in a state of passive destocking, with raw materials piling up while finished goods decreased. Later in early 2022, their inventory did not experience significant cyclical movements, but then in March and April, they again entered another round of passive inventory increase, with passive accumulation of finished goods and mild decrease of raw materials.

However, it’s important to note that expectations for higher prices might have sustained a relatively stable level of raw material inventory amid mounting external uncertainties and imported inflation pressure; otherwise it might have decreased more drastically. Thus, the manufacturing sector in China is experiencing passive restocking at the moment, likely to a larger extent than the figure below shows.

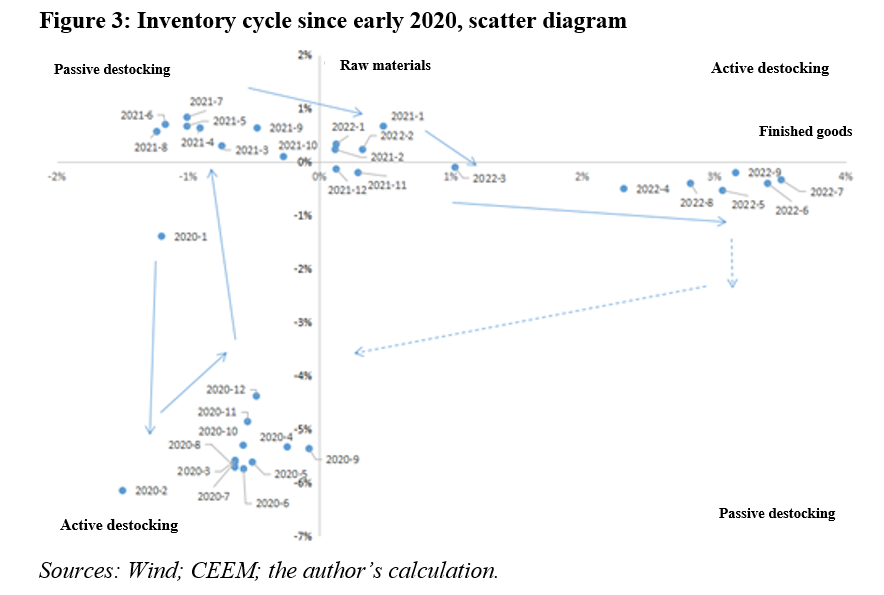

To depict inventory’s cyclical movement since 2020 more clearly, we have produced this scatter diagram. It’s clear that the onset of COVID in early 2020 initiated a sharp active destocking (bottom left), with the economy entering profound adjustments.

Later, for the best part of 2021, Chinese manufacturers were passively destocking with fast economic recovery; but by November and December that year, they had already entered a new phase of passive restocking, albeit not by much.

In the first two months of 2022, the level of inventory changed again, but not by much with no clear orientation. Another round of in-depth passive restocking kicked off later, in March and April, but the extent of which may still be underestimated since the abovementioned price change of international upstream goods has further added to domestic expectations of raw material price hike.

Going forward, from a cyclical point of view, Chinese manufacturers are likely to shift toward active destocking from passive restocking. In other words, they may produce less and try to sell more of their finished goods to reduce the inventory while their raw material holdings continue to destock. Although the stimulus previously implemented may have already taken effect, such a shift from passive restocking to active destocking could hinder economic recovery. Policy must properly guide the expectation of manufacturers so that, ideally, they skip active destocking and directly start passive destocking.

This article was published on Caijing’s WeChat blog on October 12, 2022. It is translated by CF40 and has not been subject to the review of the author. The views expressed herewith are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or any other organizations.