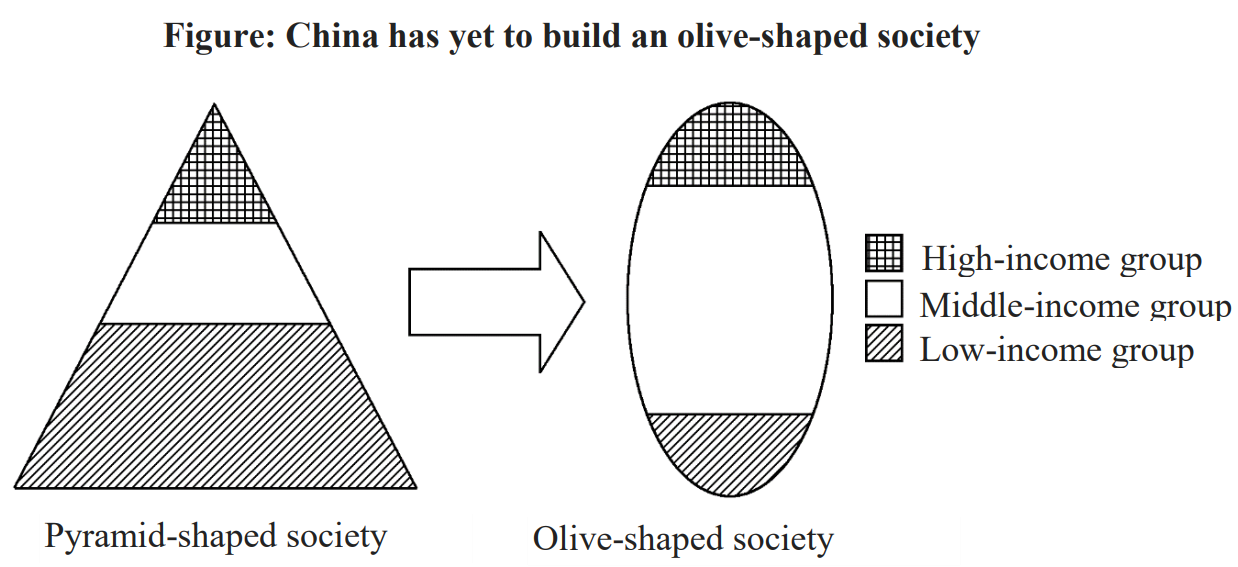

Abstract: China has yet to build an olive-shaped society with a lack of equal access to education, career development and income improvement opportunities. This article proposes policy recommendations on how China could increase social mobility and remove institutional barriers that hinder such mobility and exacerbate inequality.

Attaining an olive-shaped society is an important milestone towards common prosperity. Over 400 million of China’s 1.4 billion population belongs to the middle-income group. To give full play to the country’s super-large market in creating demand that can sustain economic growth, China has to expand the middle-income group and create an olive-shaped income structure. To this end, it will have to increase social mobility.

Since the reform and opening-up and especially after the 18th CPC National Congress, horizontal population movement has been very vibrant in China across regions, sectors, occupations and organizations with massive urban-rural and trans-provincial flows. In this sense, Chinese population and labor are already highly mobile. The increased urban-rural mobility of labor force over the past decades has contributed much to boosting farmers’ income as well as the country’s macroeconomic and productivity growth.

China still witnesses a wide gap between rural and urban household income despite the fast growth of both, with a Gini coefficient of above 0.4. An important reason behind is a lack of vertical population movement, which also indicates that China has yet to form an olive-shaped social structure and the access to education, career development and income improvement remains unequal. In other words, vertical population movement has failed to keep pace with the vibrant horizontal movement.

China has a middle-income population of more than 400 million, according to the definition of the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). That’s not large, given China’s huge total population. Based on the current standard, a typical middle-income family of three has an annual income of 100,000-500,000 yuan. Most of the Chinese people who fall into this category are urban high-income and upper-middle-income groups which account for a very moderate proportion in the total population, meaning that China has yet to build an olive-shaped social structure.

I. FACTORS STEMMING SOCIAL MOBILITY

China has yet to build an olive-shaped society because of a lack of social mobility. Then, what has been stemming its social mobility?

The horizontal flow in Chinese society had been extremely smooth for a considerable period of time since the reform and opening up, but as economic growth slows, it tends to slow—at least laterally. To a certain extent, China’s rapid economic development, improvements in education, and industrial structure adjustment opened up a wide range of options, allowing everyone to experience "Pareto improvements", or greater development opportunities without compromising those of others. Once these opportunities are diminished, social mobility will turn into a "zero-sum game" in which certain gains come at the expense of others. Generally speaking, slower economic growth is detrimental to social mobility.

China’s population is aging faster at the same time. The natural population growth rate in China, which accounts for both births and deaths, is 0.34‰ in 2021, and it is anticipated to reach zero in 2022. In 2021, elderly people aged 65 and over made up 14.2% of the population, making China an aging society according to international standards.

Population aging also reduces social mobility. At the individual level, lateral mobility tends to decline with age as people pursue fewer changes in career, place of residence, and lifestyle. This micro tendency aggregates to a macro characteristic of an aging society, which will lower the society’s overall horizontal mobility. The weakening of lateral mobility always reduces vertical mobility. At the social level, it will take time for an aging society to change and develop a senior-friendly environment for work, business, living, etc. Until then, all of the above factors will reduce social mobility.

Social mobility will inevitably decrease due to the slowing of economic growth, the aging of the population, and other factors, but there is a significant opportunity for it to rise in China if institutional barriers could be removed.

There are two indicators of urbanization in China?—the urbanization rate of the permanent residents (now at 64.7%) and the urbanization rate of the registered population (now at 46.7%). That is to say, the population with urban household registration is smaller than the percentage of people living permanently in urban areas. The 18-percentage point disparity between the two is reflected in the migrant laborers that travel to urban areas to find work. The gap also demonstrates the inability of the groups who have achieved horizontal movement to move upward. In other words, the current household registration system continues to be an institutional barrier to the growth of the middle-income group.

II. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SOCIAL MOBILITY

What policy should the government adopt to encourage social mobility?

First, promoting social mobility depends on reforms and institutional improvement. At the current stage of development, accelerating reforms can bring about increasing returns and real reform dividends, which are the removal of various institutional obstacles that hinder economic development, income growth and social mobility.

According to the target set by the CPC to basically achieve socialist modernization by 2035, the next 13 years will be an important window period for the country. During this window period, deepening economic reforms, optimizing social policies and promoting institutional improvement are crucial to gaining reform dividends. During this period, China will see its per capita GDP grow from 12,000 US dollars to 23,000 US dollars. Therefore, we can compare the level of social mobility with countries at the same stage of development by referring to the average level of social mobility in the countries with per capita GDP in the range of US$12,000 to US$23,000. While primary distribution, redistribution and third distribution each has its own unique responsibilities and roles to play, policy coordination is required to promote social mobility.

Second, primary distribution should focus on the allocation of factors of production and the rational distribution of factors of production among their respective owners. Removing the urban-rural dual structure is the most urgent reform task in this field and the next 13 years will be an important window period for implementing the task. Generally speaking, with the continuous improvement of per capita income, modernization and urbanization, the proportion of agricultural employment will keep declining. However, to close the gaps with aforementioned countries of reference, China still needs to raise its urbanization rate by 5.5 percentage points and reduce its proportion of agricultural labor force by 18 percentage points.

This requires efforts from two aspects. On the one hand, China has to remain on the track of promoting the new-type urbanization, and facilitating the transfer of agricultural labor force. On the other hand, it is crucial to narrow the gap between the urbanization rates of the permanent resident population and registered population, so that migrant workers can become urban citizens in the real sense.

In this way, reform dividends can be created on both supply and demand sides. From the supply side, by increasing the supply of non-agricultural labor force, improving the labor participation rate, and promoting resource reallocation and thus increasing productivity, economic growth rate can be improved. From the demand side, efforts to increase residents’ income, narrow the income gap and bolster consumer sentiment can considerably boost consumption, and ensure the continuous expansion of the total social demand at home so as to facilitate the formation of a large domestic market.

Third, stepping up redistribution efforts by substantially increasing government social spending. From the analysis of cross-country data, we can find a pattern: with the improvement of per capita income or per capita GDP, government spending, particularly government social spending, would account for a larger share of GDP. The phenomenon, which is named after Adolf Wagner who first found this relationship, is known as the “Wagner’s Law”. On the one hand, China’s development task in the coming 13 years is to achieve the transition from a per capita GDP of 12,000 US dollars to 23,000 US dollars. On the other hand, China is in the "Wagner acceleration period" during which the share of government social spending typically grows at the highest rate. Therefore, China should follow the law and greatly expand social spending. Only in this way can we realize the redistribution goal of making basic public services cover all people and the whole life-cycle of each individual.

Fourth, third distribution is an important complement to primary distribution and redistribution, enabling individuals, businesses, and the society to make their own contributions. Third distribution involves philanthropy, volunteer action, corporate social responsibility, etc. In addition, another important aspect is businesses’ use of technology, innovation, and algorithm for good, meaning that businesses should foster a people-centered development and operation model. This is the most important yet somewhat neglected part of third distribution. Specifically, we need to reshape businesses’ objective function and creatively include employees, users, suppliers, communities, society and environment in their production function. In this way, China’s corporate development can not only unlock endless creativity but also gain returns from both inside and outside the marketplace.

Here I will give an example of how business can promote social mobility. The age of 20-35 is generally considered to be the prime time for fertility and working. In the context of China, people aged 20-35 are still climbing up their career ladder and will reach their peak at 35 before entering a period of decline. Meanwhile, this is also the period in which the responsibility of an individual’s household tasks keeps growing heavier.

This creates a paradox between career development and family development. The constraint of extremely limited total family resources is precisely the key reason for the low willingness for childbearing and the declining fertility rate in China; meanwhile, it also impedes the improvement of employment quality, which undermines the enhancement of China’s social mobility. Given that over-intensive work pattern restrains family budget, companies can make a big difference in securing healthy and balanced development of employees’career and family through innovative and well-intentioned arrangement and support.

This article was published on CF40’s WeChat account on September 14. It is translated by CF40 and has not been subject to the review of the author himself. The views expressed herein are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or any other organizations.