Abstract: The world economy is becoming unprecedentedly complicated where multiple factors interweave with multi-dimensional implications and global growth, inhibited by public heath, geopolitical and ideological challenges, is getting trapped in a downward spiral. Pursuing economic and national security by deglobalization is a pseudo proposition. Security builds on sustained economic growth, while inflation and bottlenecks to real economy development cannot be solved unless productivity flourishes. That’s why we should place greater emphasis on reviving globalization to boost productivity, in order to address the current challenges with energy, food, commodity and minerals and promote sustained economic recovery.

The global economy is becoming complicated like never before where multiple factors are intervening and exerting multi-dimensional impacts, making it harder to depict future trajectory accurately. Based on a systematic review of statistics and facts, I would like to note several trends as follows that deserve special and further attention.

I. NEW TECHNOLOGIES ARE BEING TESTED ACROSS LEVELS WITH RESULTS MANIFESTED IN THE MARKET

There is increasing divergence between the value of real (useful) and false (useless) technologies which is manifested in statistics at both the macro and the micro level.

First, China’s sustained pursuit of scientific and technological development as the primary productive force is still playing an important part driving technological advances, but the momentum of core technological breakthroughs is marginally decreasing with the market awash with false or useless technologies, impairing the role of technology in boosting total factor productivity (TFP).

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, over the past four decades, TFP of the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), Germany, Japan and other developed economies increased from 0.776, 0.819, 0.689, and 0.823 in 1982 to 1.017, 0.995, 0.991 and 1.005 in 2019 respectively (TFP in 2017 at 1).

However, after the global financial crisis (GFC) broke out in 2007, the composite growth of TFP slowed significantly across major economies. That in the US reduced from 0.88% during 1982-2007 to 0.42% during 2007-2019; that in the UK, from 0.91% to 0.26%; Germany, from 1.32% to 0.28%; and Japan, from 0.64% to 0.33%.

This phenomenon indicates the emergence of bottlenecks stemming further improvements in disruptive technologies that can drive productivity growth and a slowdown of the integration of technological innovation and the real economy. Major economies need to explore new ways to maintain TFP growth and realize sustainable development.

Second, tech stocks which have created growth miracles are now stumbling if not diving, while bitcoins and other virtual currencies are slumping, marking a comeback of rationality in the capital market where technology stocks are no longer blindly chased after and innovation bubbles are being popped.

As of May 2022, the Nasdaq Composite Index and the Nasdaq Biotechnology Index that once went wild amid the COVID-19 pandemic have both fallen back by 23% from the height last December. Tech giants including Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Tesla have failed to stay immune. Tesla has seen its stock price plunging by almost 50% from the historical high last November.

Value of virtual currencies and other decentralized tokens and platforms with only a very limited pool of application scenarios, known as DeFi, has experienced a steep fall. Bitcoin has tumbled by over 60% since the start of the year, with its total capitalization slashed by over 2 trillion USD from last November. That’s a contraction by over 70% over just 7 months.

II. MONETARY POLICY ACROSS MAJOR ECONOMIES IS CAUGHT IN DILEMMA BETWEEN CONTROLLING INFLATION AND STABILIZING GROWTH

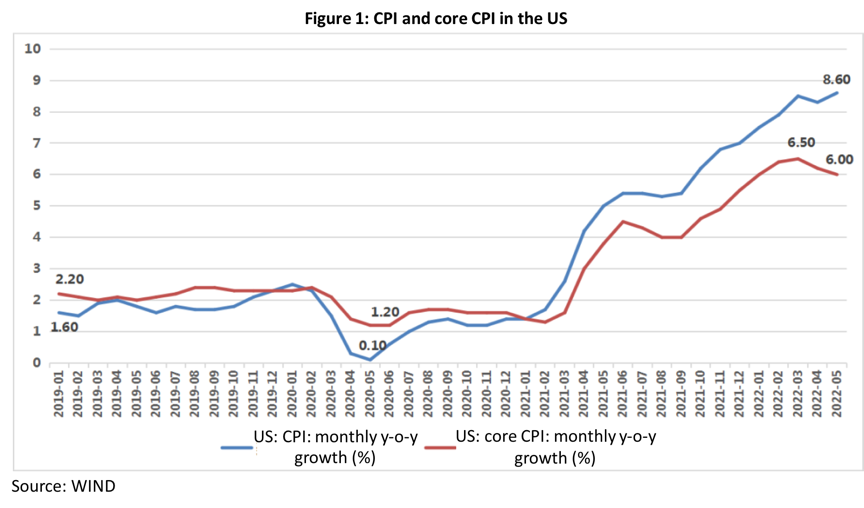

Take the US for example. Before the pandemic, CPI in the US maintained a year-on-year (y-o-y) growth of around 2%. After COVID broke out, the country introduced unprecedented fiscal stimulus, with two successive administrations mobilizing a total of 5.54 trillion USD to stimulate the economy that amounted to a quarter of GDP; that accompanied by the Federal Reserve’s ultra-loose monetary policy and new policy framework (under which the central bank more than doubled its balance sheet from around 4 trillion USD before COVID to around 9 trillion USD as of the end of May 2022) has led the CPI to skyrocket. This year, with new geopolitical tensions and the ensuing food and energy supply crisis injecting new upward momentum, the United States has recorded a whopping y-o-y growth in CPI of 8.6% in May, the highest in the recent four decades.

While inflation is surging to an all-time high, economic recovery has been stagnating with some of the indicators showing sluggish performance. For example, month-on-month growth of retail sales in the US in May dropped by 0.3%, the first decline in the year, drawing the Federal Reserve into the dilemma between controlling inflation and stabilizing growth. Market hope for a successful soft landing seems to be fading, while bringing inflation down at the cost of an economic recession is becoming a more likely, if not the only, option.

As a matter of fact, the Fed in recent years is finding it increasingly hard to maintain “independence” due to its pursuit of multiple goals at the same time. Having failed to contain inflation with timely rate hikes for fear of compromising the recovery of both the economy and employment, it now faces limited space for aggressive rate hikes which may be indispensable to bringing inflation down under the constraints of economic indicators, especially the employment rate.

According to the Deutsche Bank, the Fed needs to lift the interest rate to at least 5% to contain inflation, and that would plunge the US economy into severe recession by the end of 2023, while the unemployment rate would also rise by several percentage points ultimately. In this sense, the monetary policy dilemma has at least loosened the foundation for the classic theory that “inflation is, when it comes down to it, a monetary phenomenon”.

III. THE PURSUIT OF SUSTAINABILITY IS BESET WITH DIFFICULTIES

While climate change remains unaddressed, the world is seeing the resurgence of a host of old problems like food and public health crises and widening wealth gap. There is an unbridgeable gap that is still growing between the old and new roadblocks hindering human sustainability: any solution to climate change would worsen the rest of the challenges, and we have yet to come up with a win-win approach to reconcile the competing goals.

For example, efforts to cope with climate change have entered a dead end. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global carbon dioxide emission rose by over 2 billion tons in 2021, the largest increase in history. That to a certain extent was something unavoidable as carbon emission reduction had to be dwarfed by the overriding goal of reviving the COVID-battered world economy.

Market participants are increasingly deviating from their carbon reduction goals. This February, the European Commission approved of the Complementary Climate Delegated Act to incorporate some of the nuclear power and natural gas into the EU Taxonomy on Sustainable Finance. While tagging nuclear power and natural gas as green energies is an interim arrangement, there is no deny that the previously aggressive decarbonization plan had been frustrated. EU decarbonization faces huge uncertainties as the bloc now puts reducing the reliance on Russian energy and energy security as the top priority and its previous strategy of replacing coal-fired power plants with natural gas imported from Russia no longer works against the backdrop of the Ukraine crisis.

IV. NONECONOMIC FACTORS NOW PLAY A DOMINANT ROLE DRIVING/HINDERGING ECONOMIC GROWTH

An increasing number of cases are pointing to the fact that it’s no longer just economic activity that is driving economic results; noneconomic factors are playing a greater role, including public health crises, geopolitical tensions and ideological contention.

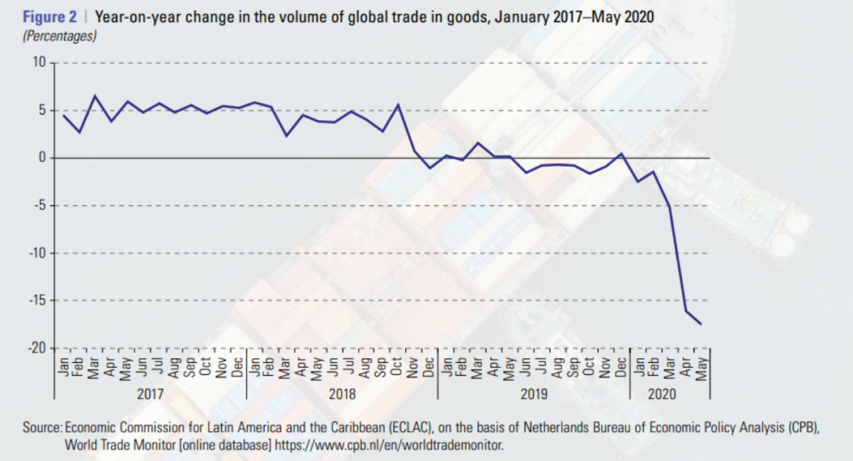

Take supply chain disruptions for example. The most important reason behind is pandemic-induced isolation and control. Countries implemented lockdowns and restricted flow of people and goods back in 2020 after COVID broke out in March and April. According to statistics from the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), in May 2020, global trade in goods reduced by 17.7% from a year ago, with that in the US, Japan and the Eurozone plunging in the first month of lockdown year on year by 30.8%, 22.1% and 22% respectively.

Second to pandemic is the trade frictions between the two largest economies in the world and sanctions implemented by the US on China. Before 2018, China was the biggest trading partner of the US while the US was the second largest trading partner of China. But after the trade war began, bilateral trade reduced year on year by 14.5% in 2019 and the importance of the bilateral relationship descended to the third place.

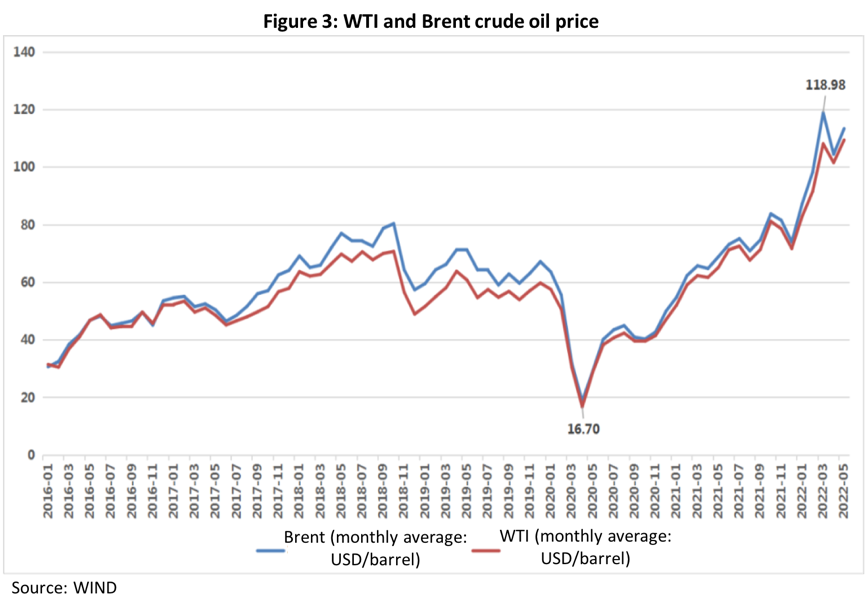

The Ukraine crisis was the contributing factor that once ranked No. 3 but recently rose to the top of the list. It severely impacted global oil, food, mineral and fertilizer supply. As of May this year, WTI and Brent crude oil price both rose by over 50% from the end of last year; the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) price of wheat, soybean and corn surged by 41%, 27% and 27% respectively from the end of 2021; natural gas price in the US had grown by an accumulated 30% or so by this April, even soaring to a 14-year high in early May.

The growing influence of noneconomic factors is miring economic policy in a vicious cycle: on one hand, sluggish growth call for increased policy supply; on the other hand, governments are causing and magnifying economic predicaments with their ever more aggressive noneconomic policies, which they ignore and justify with the “Catch-22” logic.

Research by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) suggests that removal of tariffs on major US trading partners including China and Canada could pare down US inflation by about 1.3 percentage points. However, despite the record-high inflation, US tariffs remain in place. The “invisible hand” tradition of western economies has now been abandoned. The hand of the government and politicians are waving in the air with increasingly complicated and feverish gestures. And the result of that has been as plain as daylight.

V. THE ECONOMIC CONCEPT OF “DECOUPLING” IS BECOMING HIGHLY POLICY-DRIVEN OR EVEN POLITICIZED

Market mechanism which should have played the dominant role driving economic activity is now put at the passenger seat, giving place to politics. Economic “decoupling” or “recoupling” based on supply chains have now been replaced by political decoupling or noncooperation, while supply chain security and resilience considerations with regard to decoupling are yielding to non-supply chain factors including economic and national security, if not conflict of values.

However, the indisputable fact is that heightened inflation and bottlenecks to economic growth can only be solved by boosting productivity. Global supply chain restructuring and optimization is an inevitable path to make it more resilient and reasonable, though we must bear the shocks to the current global economic landscape as a result. Sacrificing productivity runs against the underlying logic of the market economy. There is no economic security without productivity. If the bottom layer of the Maslow pyramid is undermined, upper layers would be poorly-based, and any pursuit of high-level demand such as that for security and values would be crippled.

Take supply chain relocation in recent years for example. According to a survey by the US Chamber of Commerce in 2019, because of China-US trade frictions and related factors, around 40% of the 333 surveyed American companies were considering relocating some or all of their supply chains out of China, mostly to Vietnam or other Southeast Asian countries. For example, in 2018, among the 200 major suppliers for Apple, 150 established a total of 358 factories in China which reduced to 259 in 2020; in 2019, only 17 of Apple’s suppliers had factories in Vietnam, but the number increased to 23 in 2020. Statistics from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the General Statistics Office of Vietnam show that after the China-US trade war broke out, the US share of Vietnam’s export has risen from 27% in early 2019 to 35% at the start of this year.

Relocation of manufacturing supply chains, especially labor-intensive ones, to Vietnam is a natural outcome of changes in comparative advantages, and it has positive roles to play in reducing poverty in low-income countries and price of goods. But at the same time, China is the only country in the world with the most comprehensive industrial system, and if the US decouples from China, it would hurt its businesses and people. Estimates by the US Chamber of Commerce suggest that in the decoupling scenario, airline business in the US alone would lose 38-55 billion USD of annual sales and 167,000-225,000 jobs would evaporate. Hence, supply chain relocation as a result of industrial upgrade and improved division of labor comes as a matter of course, while relocation driven by unwarranted extreme policies may lead to side effects that could have been avoided.

Ⅵ. ANTI-GLOBALIZATION FOR THE SAKE OF ECONOMIC AND NATIONAL SECURITY MAKES NO SENSE

Anti-globalization as a new trend is frequently discussed in overlapping contexts, mixed with other concepts. More often than not, it’s presented to the public to camouflage populism, nationalism, or even ideological disagreements. The optimization and upgrading of the global economic system based on cooperation have mutated into highly politicized cliques in the form of alliances or frameworks, like the "Indo-Pacific Economic Framework".

There is a different solution for each problem. The offshoring supply chain can be stabilized through some "onshoring" or "reshoring" to hedge risks and increase employment and economic security, but if a series of US initiatives, such as "friend-shoring", is further devised, it should be questioned as to how much of the economic content is present. The EU’s "Open Strategic Autonomy" is very likely to develop into a European version of "friend-shoring". They are essentially drawing political boundaries that sever the intrinsic ties of globalization and the rational distribution of supply chains, politicizing trade in the name of security, inevitably reducing the effectiveness of global resource allocation, and increasing global product prices.

But in reality, true security depends on the ongoing enhancement of both the economy and human well-being. Productivity and economic security are closely tied. Although an ineffective economy is safe, it is a static, creeping form of safety that would collapse with a single jolt. How is national security ensured if the economy is unstable?

From a national security perspective, there is no empirical evidence to date to support a significant connection between trade and security threats, even at the slightest level.

It should be recognized that, on the one hand, national security risks are based on the poverty line rather than the social welfare guarantee. If wealth is created through production and consumption, and prosperity is achieved through distribution and sharing, then national security unquestionably comes from within, though influenced by external factors, and the economic and trade cooperation between nations is more promotive than prohibitive, and more positive than negative. Therefore, limiting or banning certain exports—especially technologies—will not improve security, and imposing hefty tariffs on other countries’ goods will not benefit the country that opened this Pandora’s Box.

On the other hand, national security is no longer a simple national issue, but a balance between collective security and individual security. Never before have national security and international security been so intertwined. When a single nation's strength is no longer sufficient to address national security challenges, the need for collaboration and international coordination among major powers is even more urgent.

Furthermore, anti-globalization is essentially a political noise in the age of the digital economy. The Internet of Things is the basic requirement of the new economy. Since money and data are naturally open, pervasive, widespread, and interconnected, cutting the connections and retreating to separations is harmful to social productivity. From a pure political point of view, anti-globalization obstructs the smooth functioning of the global coordination mechanism, let alone transform and upgrade it.

However, issues like climate change, inflation, or stagflation cannot be addressed by a single country or bloc. The participation of the global community and citizens is a prerequisite and cooperation is the key.

The rate hike, as a single monetary policy tool, does not appear to be a sufficient solution to cooling inflation in the US and European economies. Rather, they should revive the globalization movement, restart the upgraded version of global division of labor in both supply chains and industrial chains which have grown more effective and resilient, and improve productivity to resolve the energy, food, commodity, and mineral crises caused by geopolitical conflicts. The basic and secondary contradictions can only be resolved by global cooperation. Any anti-globalization campaign is anachronistic.

VII. A VARIETY OF FORCES ARE ERODING THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF NATIONAL ECONOMIES AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION.

The market economy's internal logic and reaction mechanism are in disarray as a result of weakened mechanism for the efficient operation of the institutional economy. A market economy requires institutionalized economic operation and market-based economic institution operations, however, in recent years, institutions have been disregarded and their independence has been compromised.

At individual economy level, the Fed’s monetary policy objectives have been blurred by politics in recent years, and its policy instruments made to serve political goals. This has exacerbated the lag effect of monetary policy and prevented the Fed from acting in time to address macroeconomic issues through monetary policy tools.

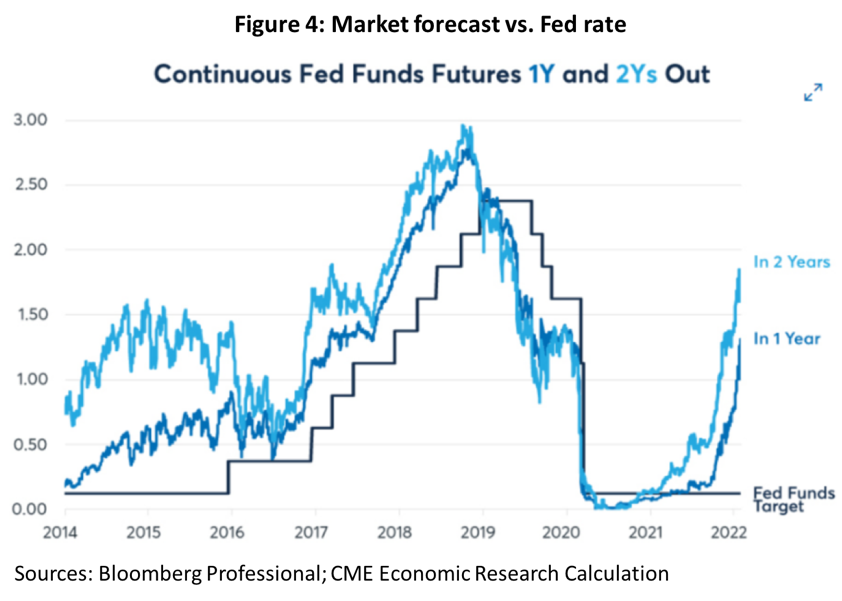

Monetary policy operations frequently lead to surprised market reaction. The Fed is supposed to be free from political influence in the formulation and implementation of monetary policy, but its delayed response in several occasions suggests otherwise, such as the 2013 taper tantrum, the withdrawal of quantitative easing after 2015, the slow hike and taper during the Trump administration, and the sudden surge of inflation during the Biden era which the Fed thought to be transitory.

The market anticipated three rate cuts in 2019 before they occurred, and when the market thought the Fed should raise rates in 2021, it didn’t begin to do so until March 2022, as shown in the federal funds futures contracts released by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which typically reflects the market's expectations of the Fed's federal funds rate.

For another example, Turkey has had high inflation in the past two years, with its CPI rising from 12.2% in early 2020 to 73.5% this May, but the president not only scoffed at rate hikes but lowered the interest rate last September from 19% to 14%, a rate that has remained unchanged since then. He has frequently dismissed central bank governors who disagreed with him, thrusting the nation deeper into the woes of soaring inflation and tumbling currency.

WTO’s Appellate Body, the “crown jewel” of the WTO system, which should have seven members for dispute settlement, now has only one left after December 11, 2019. The US has persisted in impeding the selection of judges of the Appellate Body, rejecting proposals to restart the selection process 54 times as of this June. It is both a huge impediment to the reboot of WTO’s function and a heavy blow to the multilateral trading system.

As the cases above show, independence is exercised only in a shallow and operational sense, while wheels used to be spinning are stuck in the sand, crippled by increased frictions and coordination cost. These are trends that lead to the disruptions to the economic cycle, which in turn are taken as excuses for non-economic intervention. In such a vicious circle, problems from the past are not resolved, while new issues arise.

The above analysis is an attempt to identify current and emerging issues in the world economy before developing long-term solutions. There are of course other issues not covered in this article, e.g., the debt problem, the wealth divide, the global tax imbalance, monopolies that stifle competition, AI ethics, and data security, to name just a few. The good thing is, a problem identified is a problem half-solved, and asking the right questions increases the likelihood of getting the right answer.

This article was first published on Caijing’s WeChat account on July 1. It is translated by CF40 and has not been subject to the review of the author himself. The views expressed herewith are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations.