Abstract: While China’s economic data in July missed forecasts, export and infrastructure investment have sustained strong momentum. But they have failed to translate into demand sufficient for pushing up economic growth. Under the framework combining tight credit condition, loose monetary policy and loose fiscal policy, China should focus on increasing the multiplier effect of fiscal moves and make direct impact on final consumption by creating new policy tools.

July statistics have revealed mounting downward pressure on the Chinese economy, with growth of industrial value added and fixed asset investment slowing down and social retail sales edging up by 2.7% only. This article will explore the current problems facing the Chinese economy and how macroeconomic policies can deliver better results.

I. REDUCED MULTIPLIER EFFECT OF EXOGENOUS FORCES IN DRIVING ECONOMIC GROWTH

1. Strong export and infrastructure investment growth but producing moderate effect driving growth

China’s July macroeconomic statistics, while not very much inspiring, still have several highlights including expectation-beating export growth and two-digits infrastructure growth (relative to the annual figure in 2021 at 0.2%). Past experience shows that export and infrastructure have been important exogenous forces sustaining the Chinese economy amid mounting downward pressure. But why have they failed to translate into sufficient domestic consumption and investment demand this time?

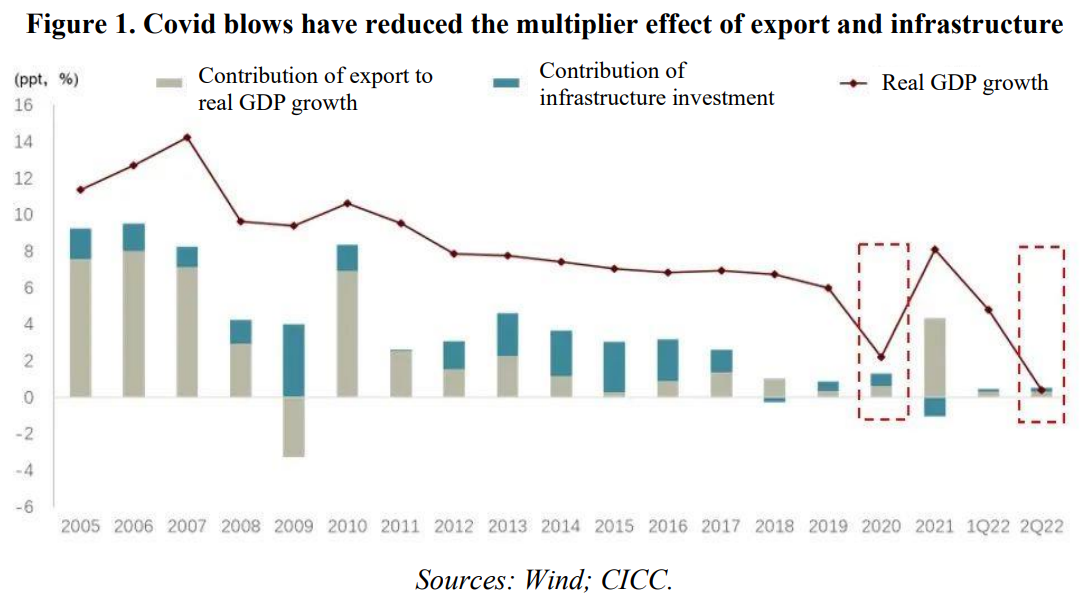

While it’s hard to estimate the multiplier accurately, the contribution of export and infrastructure to China’s GDP growth was even higher than GDP growth itself in 2020 and the second quarter of this year when Covid was dealing heavy blows. In Q2 2022, infrastructure and export alone pushed up real GDP growth by 0.51 percentage points, but the real quarterly GDP growth was as low as 0.4%, indicating that China’s domestic demand had extremely weak momentum amid Covid’s impact, thus slashing the multiplier effect of infrastructure and export, among other exogenous forces, on the overall economic growth.

2. Covid outbreak against cyclical financial downturn inducing extraordinary pro-cyclical downward pressure

What have been paring down the multiplier effect?

? Covid’s blows: While the outbreak in Q2 has been geographically restrained, the battered areas were important to key supply chains including those for automobiles, and the blows have been amplified along the supply chains and thus generating much wider impacts. The uncertainties as a result have hit market confidence and significantly impaired the role of infrastructure and export, among other exogenous forces, in driving domestic demand and investment.

? Financial cyclical adjustment, or the mid- to long-term cyclical fluctuations under the interaction of real estate and credit movements: A full financial cycle lasts for about 15-20 years. In the first half of a cycle, house price rises, businesses and households borrow more, and the two factors are mutually reinforcing in boosting credit expansion adding to upward economic momentum. Then, stronger financial regulation or the burst of the real estate bubble would kick start the second half where house price and credits form a downward spiral, with households and businesses deleveraging amid mounting pressure for asset price adjustment and debt risk exposures, adding to the strain on the economy. China is now experiencing its first financial cycle: the decade before 2018 was the upward first half, and now it is well into the second half. Such financial cyclical downturn coupled with Covid’s blows reduce the multiplier effect.

II. MACRO FINANCIAL ENVIRONMENT: TIGHT CREDIT CONDITION, LOOSE MONETARY POLICY AND LOOSE FISCAL POLICY

The second half of a financial cycle is usually characterized by a combination of tight credit condition, loose monetary policy and loose fiscal policy. “Tight creditcondition” does not mean to proactively tighten bank credits with policies; it instead refers to the spontaneous credit tightening by market participants with reduced risk preference as a result of debt risk exposure, real estate price adjustment and the pandemic’s impacts. Coping strategies include countercyclical policies to boost credit expansion such as monetary loosening and interest rate reduction to increase credit demand and loosening regulations to increase credit supply; another method is to ease fiscal policy backed by loosened monetary policy to stimulate aggregate demand.

1. Credit is not that weak, and China needs to be on guard against the loose credit policy paradox

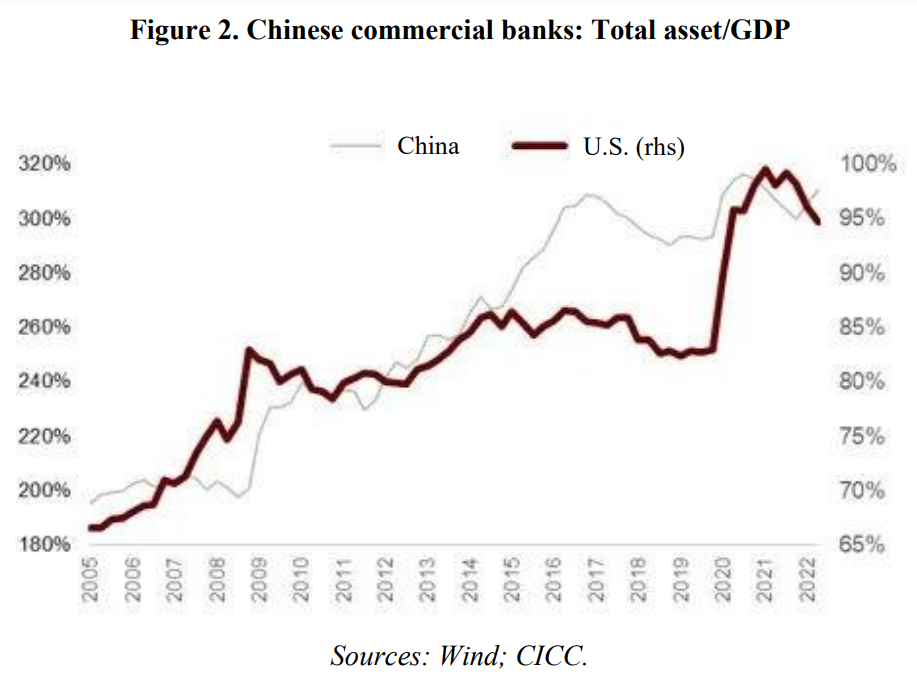

In aggregate, China’s financing environment is not very tight at the moment. While monthly credits and social financing have been more volatile recently, the aggregate amount has not been that weak, with total asset of commercial banks to GDP stabilizing at a relatively high position, in stark contrast to the United States after the outbreak of the 2008 subprime crisis when this ratio was plunging.

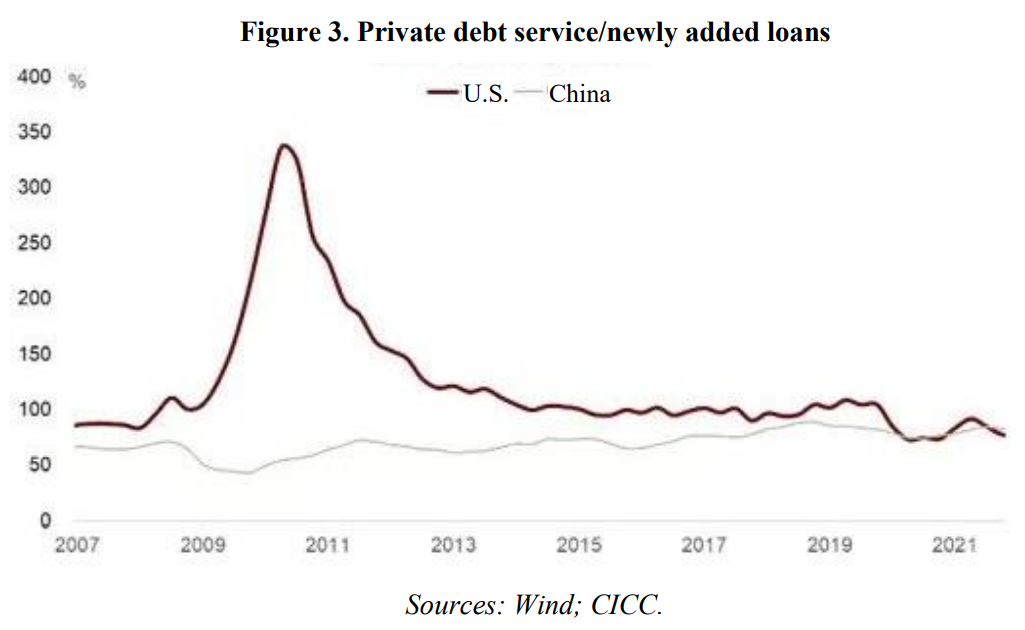

Back then, the ratio of debt service to newly added loans in the U.S. private sector was surging, indicating that more money was flowing from the real economy back to banks than vice versa, and that was a typical credit collapse. This indicator in China now is still stable, behind which is the steady rise of credit supply supported by loose credit policies like policy-based finance moves.

Credit expansion is a transmission channel during countercyclical adjustments. The Chinese policymakers’ logic in coping with the current sluggish credit expansion is that against weak demand, interest rate cuts could pare down financing costs and stimulate credit demand. On August 15, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) reduced the open market operations rate and the medium-term lending facilities rate both by 10 basis points to 2.00% and 2.75% respectively, manifesting this logic. From the U.S. experience, during both the 2008 subprime crisis and the 2020 pandemic-induced blows, monetary policy rate went down to nearly zero, which also had negative impacts such as widening the wealth gap, triggering discussions and reflections.

Of particular note, for China today, loosening credit policy still faces several medium- and long-term restrictions. The high leverage of the business and household sector was accumulated over the past decade or so during financial cyclical upturn, and it also takes time to resolve these debt risks in the second half of the financial cycle. Offsetting the spontaneous credit tightening by loosening credit policy could be costly and subject to a paradox: Since real estates are natural collaterals, if China fails to elevate the house price, it would be hard to actually loosen credits; but if house price rises again, things would be even harder when the next round of adjustments come.

2. Stronger fiscal easing moves

Based on the above analysis, we believe that policy endeavors should focus on fiscal loosening supported by monetary easing. By leveraging up, the central government could create a stable macro environment for businesses, households and local governments to deleverage, and only loose fiscal policy could truly achieve countercyclical effects. The U.S. experienced a period of “zero credit growth” which to a large extent was owed to the strong fiscal easing measures.

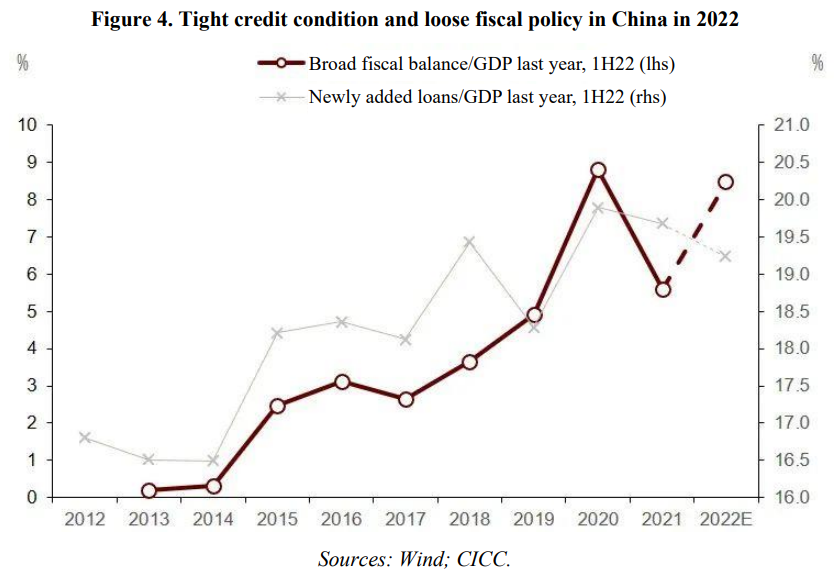

Fiscal easing is also the main direction of macroeconomic policy now in China. Deficits, government funds, profit delivery by the PBC and past outstanding fiscal balance (namely the deposit of the central government at the central bank) taken together, we estimate that this year, China’s broad fiscal expansion would exceed that in 2021 by 3 percentage points. In contrast, in 2021, China’s fiscal revenue-expenditure balance narrowed by 3 percentage points. At the same time, stronger coordination between monetary and fiscal policies this year has further supported basic money issuance thus facilitating stronger synergy between eased monetary policy and loose fiscal policy.

III. ADDING FISCAL TOOLS TO FACILITATE ECONOMIC RECOVERY AND RESTRUCTURING

The question now is, as fiscal expansion strengthens, why the transmission effect seems not to be so strong? Traditional tools of fiscal policy including infrastructure investment, tax and fee cuts, and policy-based finance are becoming less effective in pushing up demand. Hence we need to redesign the toolbox of fiscal policy to directly boost consumer demand.

1. Traditional fiscal tools are becoming less effective in boosting demand.

Important fiscal tools like tax and fee cuts or policy-based finance are directed at businesses. In the early stage of the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020, these measures that aim to protect market entities have helped avoid large-scale corporate bankruptcies under the pandemic-induced shock and laid a solid supply-side foundation for the economic recovery in the second half of 2020. Such policies rest on the assumption that the pandemic only causes a short-term or one-off shock. However, the pandemic shock lasts longer than expected, turning from a “one-off” shock into an “enduring shock” with no clear end in sight.

Amid huge uncertainty, even if companies can keep the current employees on the payroll, they lack the motivation to add jobs and expand reproduction, thereby leading to high youth unemployment. Meanwhile, under a one-off shock where the structure of demand would not change dramatically in the short term, policies that protect supply entities will not result in a mismatch between supply and demand. But when the pandemic turns into a lasting shock, the demand structure is also changing. If we stick to the current policies, supply may not be able to match demand, which is not good both for stabilizing growth in the short term and structural adjustment in the long term.

Infrastructure investment, another traditional tool of fiscal policy, not only faces the challenge of declining multiplier effect, but also structural problems. The crux of the current unemployment issue lies in high unemployment rate of young people, including college graduates. Thus, it remains to be seen whether increased infrastructure investment can provide jobs that match the human capital.

2. Designing a policy toolbox that directly boosts consumer demand

The pandemic shock is an important cause for the declining effect of traditional fiscal tools in driving up demand. To address the problem, one way is through optimizing pandemic prevention and control measures in due course. Another way is designing the policy toolbox that directly boosts consumer demand. Production is only the means, while consumption is the end, since the latter decides whether producers will expand employment and production. Against the backdrop of continuous pandemic-induced shock and great uncertainty of future expectations, stimulating consumption is the only way to improve producers’ expectations, keep market entities’ operation stable, and recover the multiplier effect of exogenous variable.

On August 18, the State Council’s executive meeting announced greater efforts to secure the basic livelihood of people in need. First, the coverage of subsistence allowance will be expanded to include eligible people on a timely basis, and a one-off living subsidy will be given to recipients as soon as possible. Second, greater assistance will be extended to people in difficulty and a one-off relief policy will be implemented as soon as possible. Third, the mechanism of raising social benefits pro rata with price increase will be adjusted on a time-limited basis; the mechanism will be extended to cover those receiving unemployment subsidy and those nearing the eligibility threshold of subsistence allowance, and the year-on-year CPI monthly increase threshold, will be lowered to 3 percent from 3.5 percent. Fourth, the central government will provide subsidies for the increased local expenditures from expanding the coverage of subsistence allowance and other relief schemes and adjusting the pro rata price increase subsidy mechanism. We believe these are important policy updates. For policies that aim to directly boost consumer demand, the following aspects merit further consideration:

1. Amid the ongoing pandemic shock, distributing subsidies through fiscal measures directly to people is an effective way to shore up the post-pandemic recovery and improve the efficiency of matching supply and demand. The Covid-19 pandemic mainly causes a supply shock. As the pandemic drags on, the resulting uncertainty will inhibit corporate investment more. The fragile industrial chain due to the pandemic shock also makes it more difficult to create demand through more supply. Therefore, fiscal policy targeted at businesses is effective in the short term, but might be less so in the long term. However, it is not the case for consumption, especially since the low- and middle- income groups have rigid consumption demand. Weak consumption is mainly attributed to low income. Thus granting one-off subsidies that benefit all people or low- and middle- income groups can unlock the consumption demand.

2. Providing more relief for people in need like the unemployed underscores the role of public policy as the social safety net against the ongoing pandemic shock. The impacts of the pandemic on economic activities are asymmetric, whether in terms of industry, demographics, or region. Facing such an asymmetric shock, public policy needs to serve as the social safety net. For groups in need like the unemployed, the root cause of their hardship is not laziness, but their sacrifice for the pandemic prevention and control efforts to protect the whole society. As the pandemic drags on, people’s expectations of their future income will be even gloomier, adding to the necessity for the whole society to cover the costs of pandemic prevention and control. This requires public policy to serve as social protection to compensate for some of these people’s losses.

3. Improving the protection mechanism for vulnerable groups including subsistence allowance and rural pension funds can help achieve both the short-term goal of stabilizing growth and the long-term goal of structural adjustment. Take subsistence allowance as an example. A large proportion of people, especially rural population, haven’t been covered by the program. We could thus expand the coverage of subsistence allowance to rural people in need. On the other hand, we can raise the standard of basic pension scheme for urban and rural residents and set up a minimum non-contributory pension scheme. Currently, the basic residential pension scheme mainly covers rural population, and part of urban population who do not enroll in the pension scheme for urban employees. According to our estimation, the average benefits of basic pension for urban and rural residents are only half of the rural poverty line, and around 5% of the average benefits of the pension scheme for urban employees.

4. Special childbirth subsidies not only can support economic recovery in the short term, but also can enhance growth potential in the long term. Take developed economies that suffer low birth rate as an example. The greater the level of subsidies in these countries, the higher the birth rate tends to be. Specifically, childbirth subsidies can be divided into two types: direct and indirect subsidies. Direct subsidy policy can increase family income through three major forms, i.e., baby bonus, parental allowance and tax credit. Indirect subsidy policy supports childbearing mainly through lowering its opportunity costs, such as building inclusive childcare centers. While improving maternity leave system such as maternity leave and parental leave, we could also draw on the experience of developed economies to increase fiscal support for inclusive childcare and enhance cash payment including parental allowance. These special subsidies not only can directly reach consumers and boost the economy, but also ease the constraints on labor supply and help achieve long-term sustainable growth.

II. DEBT SUSTAINABILITY: HOUSEHOLDS SHOULD LIVE WITHIN ONE’S MEANS, WHILE THE GOVERNMENT SHOULD DECIDE TAX REVENUE BASED ON THEIR SPENDING

Fiscal support needs to step up, whether to provide one-off subsidies for most people (such as subsidies for low- and middle- income groups and targeted subsidies for groups affected by the pandemic) or to permanently improve the protection standard for a few vulnerable groups (such as by increasing the coverage rate of subsistence allowance and benefits of the rural pension scheme). This can be achieved by adjusting the structure of spending, such as reducing infrastructure investment and transferring the money to consumers. More importantly, public debt can also play a great role. To cope with the unprecedented pandemic shock, raising government debt to support affected businesses and individuals not only reflects the protective role of public policy for the society, but also can prevent sending the economy into a “coma” and hurting the growth potential.

There are three common concerns regarding raising public debt for transfer payment: first, transfer payment might incentivize freeloading and breed dependency; second, the scale of public debt might be too large to be sustainable, which is bad for economic development in the long term; third, massive public debt may fuel inflation.

As for the first concern, the occurrence of “dependency” is positively correlated with the duration of subsidies. Hence one-time subsidies to people affected by the pandemic would not encourage “freeloading”. In addition, empirical studies have shown that subsistence allowance is very effective in eliminating poverty in China’s urban and rural areas, and meanwhile does not demonstrate substantial negative incentives since it does not significantly reduce the working hours of recipients. In addition, childbirth subsidies can increase future labor supply and help improve long-term growth prospects and tax base.

In terms of debt sustainability, we need to distinguish the government’s perspective from that of households. Each household faces the constraint of making ends meet, so they have to “l(fā)ive within their means”. However, government spending can influence aggregate demand and supply, thereby making an impact on economic growth. In other words, tax revenue is the result of government spending. In this sense, the government can affect its revenue through its own spending behavior. The sustainability of public debt depends on whether the government can control its tax revenue based on spending.

This does not mean that public debt can pile up indefinitely; inflation will put a damper on it. Currently, China’s inflation remains at a low level which can tolerate an increase to a certain degree. But counter-cyclical adjustment is a delicate balancing act and risks overcorrection which will bring some negative effects. Therefore, policy tools should weigh benefits and costs. If we compare the two options of loosening fiscal policy and expanding credit, the advantage of direct fiscal subsidies to consumers is its effectiveness in stabilizing growth, and the risk of overcorrection is higher inflation; credit expansion is less effective in stabilizing growth, and the risk of overcorrection is greater debt burden on businesses and households. Based on the current situation, the negative effect of loose fiscal policy, especially direct fiscal subsidies to consumers, might be relatively smaller.

This is an excerpt of the report Facing Reduced Multiplier Effect, Macroeconomic Policies Should Directly Boost Final Consumption released by CICC Global Institute on August 19. This article does not seek to provide any investment advice. The views expressed herewith are the authors’ own and do not represent those by CF40 or any other organizations. It is translated by CF40 and has not been subject to the review of the authors themselves.