Abstract: Over the past decade, China’s inflation has remained at a low level. The pandemic-induced shocks have led to weakened demand and a sharp decline in supply, which contributed to a low inflation rate. But with the gradual recovery of demand, China’s inflation might rise sharply. Despite that, China should stick to the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies and learn to tolerate high inflation.

Over the past decade, China’s inflation rate has remained low, with CPI growth averaging around 2%. In Q1 2020, China’s economy was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic growth declined 6.8%, and meanwhile, CPI rose 4.9% compared with a year earlier. After that, CPI growth fell, even turning negative at the turn of 2020-2021, but rebounded to 2.3% in October 2021, the highest point since the pandemic broke out. Since then, CPI growth has slowed down, standing at 2.1% this May.

From July 2019 to December 2020 (except for January 2020), China’s PPI grew at a negative rate. In 2021, PPI rebounded rapidly, hitting a record high of 13.5% in October. After that, PPI growth gradually fell to 6.4% in June 2022.

The surge of PPI in October 2021 stoked market fear that high PPI growth could eventually turn into high CPI growth. The fear, however, has not translated into reality. While countries around the world are worrying about the soaring inflation, China does not have the problem.

This begs the question of whether China’s inflation will suddenly take a turn for the worse in the foreseeable future (such as in 1-2 years).

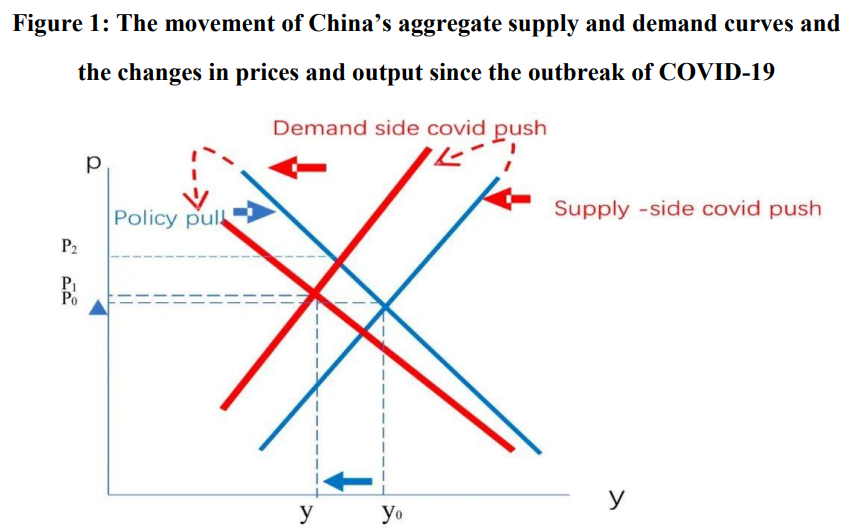

Wtih a given aggregate supply curve, an increase of aggregate demand (the demand curve shifts to the right) will lead to higher output and prices, and vice versa. Under With the demand curve given, disruption to supply ( the supply curve shifts to the left) will lead to lower output and higher prices, and vice versa. When the supply and demand curves move in tandem, the inflation level is decided by the relative change of aggregate supply and demand (Figure 1).

Since the pandemic broke out in Q1 2020, China’s economy has been disrupted on both the supply and demand sides. In certain periods, the supply shock dominated, while in others, lack of demand prevailed. Overall, China’s post-pandemic economy is characterized by the coexistence of weak effective demand and supply shocks.

As shown in Figure 1, the pandemic disrupted the supply chain, moving the aggregate supply curve far to the left. When China’s output decreases, its inflation is supposed to soar (P2 in Figure 1). However, the pandemic has also undermined effective demand. Thus despite the sharp decline in output (from y0 to y1), prices only witnessed a modest rise (P1 in Figure 1).

As the decrease of aggregate demand is smaller than that of aggregate supply (which is an empirical rather than a theoretical question), prices would still rise (Figure 1, p1>p0). If prices fall instead of rising, it means that the aggregate demand curve shifts more to the left than the aggregate supply curve, which could lead to further drop of output.

Facing the dual shocks to aggregate demand and supply, the government must make a choice. If the government regards the declining growth and rising unemployment as the main threat, it must adopt expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to push the aggregate demand curve back to its original place, or even further to the right. In this case, if the supply shock is not eliminated, price levels will rise substantially (p1 in Figure 1).

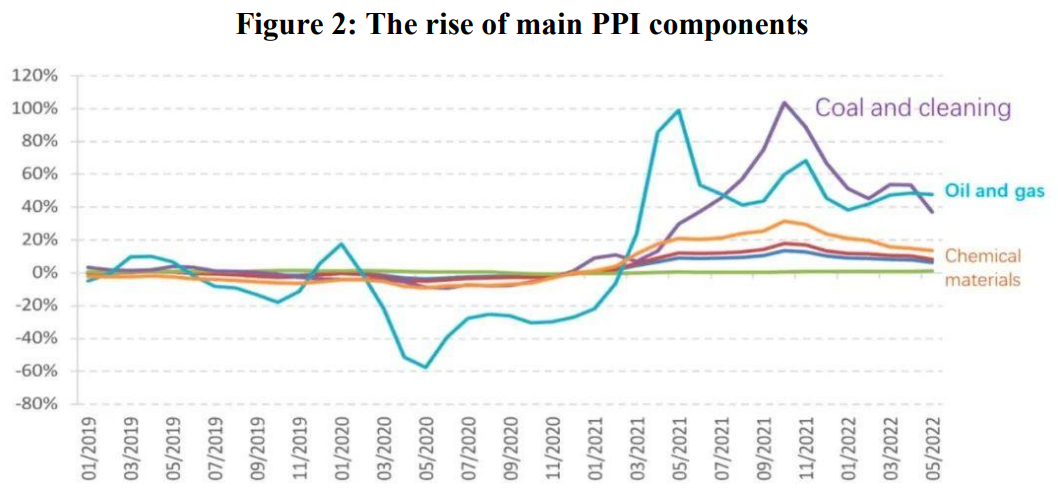

To examine the nature of China’s inflation, we should first figure out the causes for the rapid rise of PPI since Q1 2021. During this period, three types of goods have contributed most to the increase of PPI, namely, oil and gas, coal and cleaning, and chemical materials (Figure 2). The question is whether the rising prices of oil and gas in China during this period are caused by demand pull or external supply shock.

After the pandemic broke out in 2020, global oil prices once dipped to negative territory, and domestically the prices of oil and gas also plummeted (Figure 2). In April 2020, global oil prices started to rebound; meanwhile, the decline of China’s oil and gas prices began to slow down, and has reserved the trend since the beginning of 2021, rising sharply before hitting a record high in May 2021. Since the second half of 2021, China’s oil and gas prices have still been rising, though at a lower rate.

It can be seen that China’s oil and gas prices move in tandem with the rise of global crude oil prices, whereas China's control over oil and gas prices has made the domestic price movement less volatile than the global one. Overall, the rise in China’s oil and gas prices is mainly the result of supply shock rather than demand pull.

China’s coal prices started to shoot up since 2021, with the growth rate peaking at 13.5% in October 2021, which made coal prices one of the most important causes for the record high growth of PPI in October 2021. The reasons behind the surge in coal prices in 2021 are known to all, which will not be elaborated here. Simply put, it is caused by lower supply instead of higher demand, as is the case for the rise of chemical product prices.

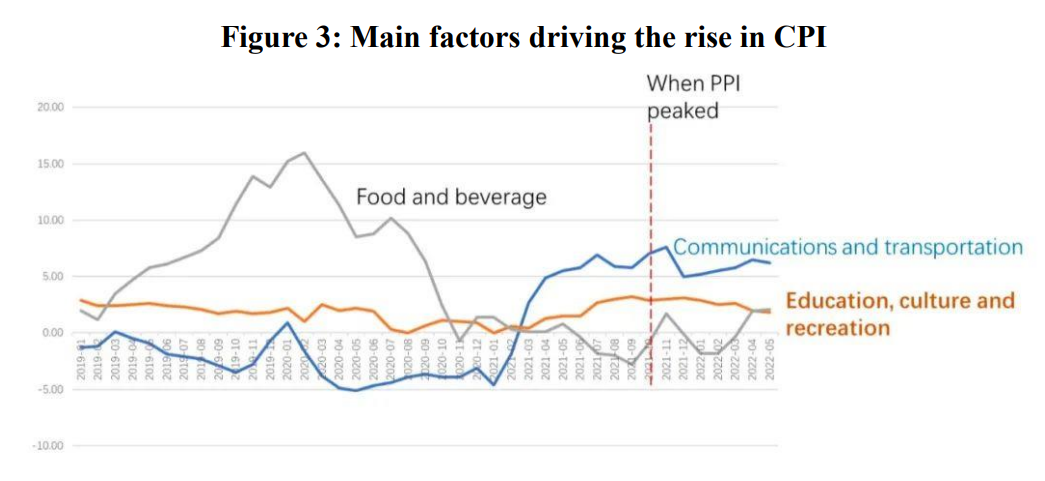

Regarding CPI, the three largest contributors to its growth are communications and transportation, food and beverage, and culture, education and recreation, of which, the prices of communications and transportation recorded the rapidest rise (Figure 3). Clearly, the demand for transportation has fallen sharply due to the pandemic. The rise in communications and transportation prices can only be attributed to rising energy prices such as oil and gas. It's not hard to imagine that communications and transportation prices would have risen much more if not for the weak demand. The rise in food prices is largely due to supply-side shocks as well. As for the reasons behind the increase in the prices of culture, education and entertainment activities, further analysis is required.

It can be seen that the increase in PPI has only partially converted into an increase in CPI (such as communications and transportation prices) due to the lack of effective demand. This, in turn, means the reallocation of profits or losses among many firms along the supply chains.

In fact, many large state-owned enterprises at the upstream of supply chains that are engaged in the supply of bulk commodities saw much improved profitability in 2021 compared to 2020 (with a base effect at work here); however, many manufacturing enterprises at the downstream were far less profitable. Due to weak final demand and institutional reasons, producers of products in the CPI basket usually lack bargaining power, and can only accept reduced profits or exit the market, so they can hardly transfer the increase in costs to final consumers. According to a study conducted by CF40 researchers, part of the increase in PPI was transferred abroad through the rise in export prices.

In short, the growth of PPI is significantly higher than that of CPI, and the slow narrowing of the gap between the two further shows that China's inflation is mainly caused by supply shocks. Weak demand has curbed the deterioration of inflation at the cost of economic growth.

Now we have to answer the three questions below:

Q1: At what level will external supply shocks, such as rising global energy and food prices, persist?

Q2: Is China also facing the threat of inflation?

Q3: If China faces greater inflationary pressure in the post-pandemic period, should the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies still be implemented? Should China tolerate higher inflation in the future?

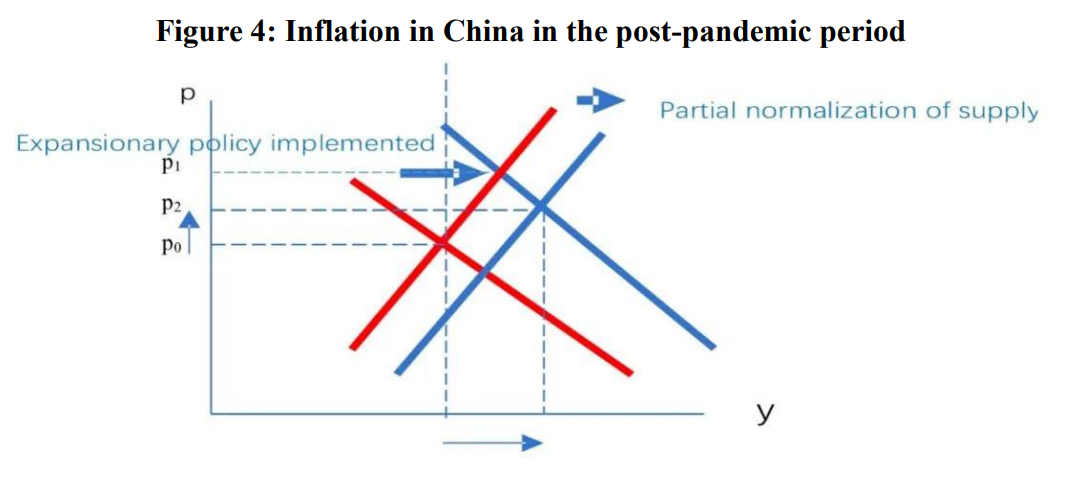

I’m not sure about the answer to the first question, but I would say yes to the last two. First, as the pandemic eases off, effective demand will pick up. Second, the government will keep implementing expansionary fiscal and monetary policies in order to stabilize growth, thereby further increasing effective demand. Third, some inherent price cycles in the country (such as the "pork cycle") may come into play.

When the aggregate supply curve remains unchanged, the rightward shift of the demand curve means that the inflation pressure caused by the leftward shift of the aggregate supply curve will build up (Figure 4, prices will rise from p0 to p1). A further rightward shift of the demand curve means a further increase in demand. Of course, supply chain recovery will lead to an increase in supply, which will help reduce inflationary pressure (Figure 4, p1 falls to p2). However, in the initial stage, the intensity of inflationary pressure caused by the rightward shift of the aggregate demand curve is likely to be greater than the mitigation effect caused by the rightward shift of the aggregate supply curve (Figure 4, p2>p0). Therefore, as the pandemic eases off, China is very likely to see rising inflation. It needs to be pointed out that when the government makes efforts to stimulate demand, it must ensure a high level of investment, so as to facilitate sustained increase of supply.

In the first quarter of 2022, China's economic growth was significantly lower than expected. However, China has the need and capability to maintain a high economic growth rate. Moreover, an even more worrying phenomenon is that the youth unemployment rate reached an unprecedented level of 18.4% in May 2022. Even if China falls short of its 5.5% growth target, it should try to recoup the lost growth in the first half of the year. To this end, China needs to maintain expansionary fiscal and monetary policies even if inflation rises. In other words, China should tolerate a higher level of inflation. But the acceptable level is determined by social and political considerations rather than economic ones. Finally, it should be noted that the choice and effectiveness of China's economic policies will largely depend on the development of the pandemic and the control measures.

The article is based on the author’s speech at the CF40 - Euro 50 - PIIE Joint Conference on “Coping with the Return of Inflation” on July 1, 2022. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the author. The views expressed herein are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations.