Abstract: Welfare state building is a must to do during the modernization of countries around the world. In the case of China, the authors put forward that, either from the perspective of general laws or focusing on the challenges China is faced with, it needs to increase government spending to improve social welfare in an accelerated pace in the coming 10 to 20 years. They also emphasize that during the process of welfare state development, the government must strike a balance between making the utmost effort and fully considering its financial capacity.

I. INTRODUCTION

Welfare state is a general concept. Countries around the globe have found many commonalities in the practices of developing a welfare state. Therefore, the discussion about building a welfare state in China naturally has to refer to general theories and international experience.

Meanwhile, we should also recognize the practical and urgent needs of China's economic and social development for the social welfare system, from which the discussion should start. China's institutional arrangements and their uniqueness must be given special attention.

To this end, we have to first reveal the characteristics of China's developmental changes and challenges the country faces, and then look for relevant experience in the economic history, as well as relevant logical correspondences from economic theory.

The most prominent changes that China undergoes are the arrival of two landmark turning points.

The first important sign of the change is that, measured by per capita GDP, China has joined the group of high-income countries as expected. China's per capita GDP reached 12,551 US dollars in 2021 based on the current US dollar and the average exchange rate. The World Bank’s newly revised income grouping for 2021-2022 uses $12,695 as the threshold for high-income countries (Hamadeh et al., 2021). This new starting point is of positive significance as it means China's leap over the middle-income stage at least in a statistical sense. However, this does not mean that China's economic growth can be rest assured from now on. Given that the per capita GDP of US$12,695 is the threshold level for the high-income group, which is only 28.9% of the average level of high-income countries (US$44,003), China still has a long way to go to increase its per capita GDP and boost sustainable high growth. If China fails to maintain a reasonable growth rate, it will be exposed to the risk of stagnation and even regression.

While joining the group of high-income countries, China sees another important change, namely the accelerated demographic transition beyond expectations. This brings new challenges to China's economic growth that are either unforeseen or systematically underestimated in the previous forecasts. In 2021, the natural growth rate of China's population was 0.34‰, close to zero growth. This also means that China is about to enter an era of negative population growth, about a decade ahead of the prediction made by the United Nations in 2019. In the same year, the proportion of the population aged 65 and over reached 14.2%, marking China’s entry into an internationally recognized ageing society about five years ahead of schedule (UNPD, 2019).

We can understand the implications of this unexpected demographic turning point for China's economic growth in two ways. First, as the population is about to peak and population ageing accelerates, the working-age population will see a rapid fall while the dependency ratio a sharp increase, leading to unfavorable changes of the labor supply, human capital improvement, return on capital and productivity. The potential growth rate will continue to decline, making it even more difficult to realize the desired growth rate. Second, with the blow to household consumption brought by reduced total population, age structure and income distribution, insufficient aggregate demand will become a normalized constraint for economic growth. This means that, no matter from the supply side or demand side, it won’t be easy to achieve the economic growth rate set for the long-term goal.

In fact, studies on the so-called middle-income trap show that the factors that prevent middle-income countries from growing into high-income countries will continue to exert an effect even after countries successfully leap over the trap and drag down economic growth.

For example, Eichengreen et al. have published multiple papers revealing that the middle-income trap is characterized by a marked slowdown in a given period of high-growth countries. Some of the slowdowns are both large and difficult to reverse. In one of the articles, they found that some countries and regions witnessed significant deceleration in the growth rate when per capita GDP levels were near $10,000 to $11,000 and $15,000 to $16,000 in 2005 PPP-adjusted dollars (Eichengreen et al., 2013). In their study, 24 countries have experienced significant slowdowns since 1987, among which 15 economies were in the high-income group according to the World Bank income grouping. Some of them are adversely affected in the longer term. That is to say, crossing the threshold of high-income group in the statistical sense does not automatically ensure smooth and sustainable development.

In the face of economic growth deceleration factors, especially demand-side factors that may prevent economic growth from reaching its potential growth rate, expanding social welfare spending is undoubtedly beneficial. Expanding government spending to boost social protection, social welfare and mutual aid is actually required by China’s determination to promote modernization and common prosperity. Therefore, the debate about the welfare state is not really about whether to do it or not, but about where the funds for social welfare expenditure should come from.

We can understand the question as how to achieve the unity between providing better social welfare and acting within actual financial capabilities during the process of increasing social welfare. This paper will demonstrate the general principles and laws of social welfare expenditure and their special implications to China from both theoretical and empirical aspects, so as to reveal the policy implications and provide policy recommendations.

II. SOCIAL WELFARE EXPENDITURE IDENTICAL EQUATION: PHILOSOPHY AND REALITY

When reviewing theoretical debates about developing welfare states, we found that researchers generally put forward and uphold their own propositions from two directions, based on two generally opposing models or types, namely, the residual and institutional models of welfare (Titmuss, 1974). The difference between these two models is not manifested in social protection in reality, but mainly in the concept itself.

The former model emphasizes the role of the market, individuals, families and social organizations, while the government only needs to offer social assistance and limited basic living security to the most disadvantaged groups. The latter model holds that, as a redistribution mechanism, social welfare should be the responsibility of the government in any society and at any stage of development. Although the debate between opposing ideas has been protracted, and each of the concepts has produced very different practical consequences, a trend of convergence in practice has been acknowledged globally. This trend of convergence is mainly a result of trial and error in the practice of countries in dealing with practical challenges.

The improvement of the social welfare system, or the emergence, development and rise and fall of the welfare state, are not only based on some specific political philosophy, but also influenced by the social ideological trend of a specific era, and shows the institutional changes induced by the needs of economic and social development. We have studied the most influential economics literature and would like to introduce two perspectives to understand social welfare system.

One type of literature links the necessity and inevitability of social welfare development with the stages of economic and social development.

Walt W. Rostow (2001) divided economic development into five stages: traditional society, preconditions to take-off, take-off, drive to maturity and age of high mass consumption. In later writings, he also added a sixth stage characterized by the pursuit of a higher quality of life. Logically, the fifth and sixth stages undoubtedly put higher demand for public services.

John Kenneth Galbraith (2009) came up with the concept of "affluent society", pointing out the huge discrepancy between abundant social wealth and private production, and a lack of public service. He believes that to solve the problem of social poverty in an affluent society, the government needs to provide more public goods and services by means of redistribution.

Michael Porter (2002, Chapter 10) divided economic development into four stages: factor-driven, investment-driven, innovation-driven, and wealth-driven. He believes that the wealth-driven stage will encounter a series of challenges resulted from slowed economic growth, for example, the contradiction between economic development goals and social value goals, and the discrepancy between insufficient economic growth and expansion of welfare expenditures.

Another type of literature regards addressing population challenges as an inevitable requirement of the welfare state.

Gunnar Myrdal was the first to recognize the role of population factors in the development of a welfare state. As early as the 1930s, the Myrdals warned of the possible consequences of slowing population growth or a reduction in the total population. They upheld that the burden of breeding and raising children be transformed from a family responsibility to a social welfare system that embodies the idea of mutual aid, thereby encouraging people to marry and have children. The spread of Myrdal's thought and policy recommendations based on it not only drew a blueprint for the development of Sweden's social welfare system, but also exerted a profound impact on the policies of other countries (Chen Sutian, 1982, Chapter 3; Barber, 2008, Chapter 10; Yoshikawa, 2020, pp. 47-49).

John Maynard Keynes and Alvin Hansen gave very similar speeches in 1937 and 1938 respectively, pointing out the trend of stagnant population growth in the United Kingdom and the United States and arguing that if governments fail to improve social welfare and income distribution to offset insufficient demand for investment and consumption, economic growth would suffer catastrophic consequences (Keynes, 1978; Hansen, 2004).

In addition, the concept of secular stagnation proposed by Hansen in that year is widely used by some contemporary economists to demonstrate the impact of population aging on economic growth (Summers, 2016).

Learning from the painful lessons of capitalist development in the contemporary era, China needs to first consider the stage of its economic development and the practical challenges. The question is longer whether we should develop a welfare state, but when to develop it and the level of welfare we want to achieve.

Therefore, we can use a concise formula to illustrate how to achieve the organic unity of making the best effort to increase social welfare and considering one’s financial capacity. This can be called the social welfare expenditure identical equation, written as E-B≡0, where E represents the actual expenditure of social welfare, and B spending capacity of a society.

This identical equation emphasizes that the difference between actual expenditure and financial resources is always equal to zero. Once this identical equation fails, it either means there is room to increase social welfare expenditures, or there is a need to adjust social welfare policies.

For example, if E-B>0, it means that the level of social welfare has broken the financial constraints that are placed to keep expenditure sustainable, forming a capacity gap. In this case, it is necessary to reduce expenditure according to a government’s actual financial capacity. If E-B<0, it means that the level of social welfare has not yet reached the potential determined by financial resources, forming an effort gap, a situation where it is necessary to increase the actual expenditure to truly use up the resources. Adhering to the identical equation requires not only strict adherence to the concept, but also ability and skills to maintain the balance.

Simple as it may look, the formula contains rich meanings and is closely related to a series of theoretical discussions and policy practices. The identical equation emphasized here challenges traditional views on the social welfare system, especially the policy ideas formed under the influence of neoliberal economics since the 1980s, favoring residual welfare based on the trickle-down effect and the denial of social redistribution.

Having suffered enough from the economic, social and political consequences of neoliberal policy practices, people’s understanding about welfare state development in theory and practice has changed in recent years. However, only by breaking the traditional concept of public finance, especially austerity policies advocated by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the Council of the European Union among other institutions and countries influenced by the neoliberal concept, and the institutional constraints on fiscal spending, can it be possible to return to a normal track in practice. And this requires taking the social welfare expenditure identical equation as the principle for developing a welfare state.

In addition, although it is called the social welfare expenditure identical equation, the variables in the formula are in accordance with certain laws and keep changing with economic development. Below, we will understand this change and its policy implications based on empirical facts, combined with general laws and the special challenges China faces.

III. WAGNER’S LAW: GENERAL LAWS AND CHINESE REALITIES

In the economics literature, there is a stylized fact named after Adolf Wagner, which is widely quoted and empirically tested. It is called Wagner's Law.

According to Wagner’s Law, as per capita income increases, people's needs for social protection, antitrust and regulation, compliance and enforcement, culture and education, and public welfare will keep rising. Since the supply of public goods usually depends on government spending, the ratio of government expenditure to GDP shows a trend of gradual increase (Henrekson, 1993).

This general law may be too general as various government functions and their expenditures of different nature and objectives are all categorized as "government expenditure". In particular, the fiscal item of government expenditure also includes the government's spending on economic activities. Such activities and corresponding expenditures often vary enormously from time to time due to the division between market-oriented and non-market-oriented preferences of the economic system. Although limited by the availability of statistical data, we sometimes have to resort to this all-encompassing concept of government spending in empirical research, but our focus always lies in the government’s spending in social protection, social welfare and mutual aid.

Correspondingly, in addition to the correlation revealed by Wagner that the proportion of government spending increases with economic development, the aforementioned theories related to welfare state development also reveal the causal relationships in a targeted manner. The statistical fact of increased government spending for social welfare, especially the rising expenditure-to-GDP ratio can test Wagner’s Law in a narrow sense

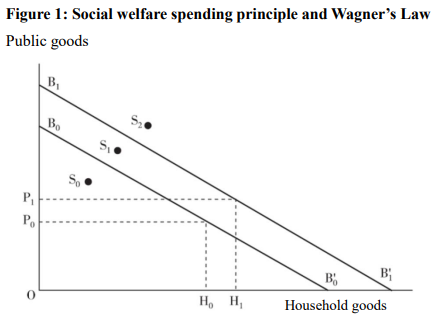

We would like to further explain the social welfare expenditure identical equation in the context of Wagner's Law with the help of Figure 1. The figure contains the following important information.

1. The movement of the line from B0B'0 to B1B'1 means that with the increase of per capita GDP and labor productivity, the total budget constraint curve that is used for measuring household consumption and public goods expenditure moves upwards and rightwards regularly.

2. (P1-P0) represents the increase in public goods expenditure of the whole society as the budget constraint curve moves upwards and rightwards; and (H1-H0) represents the increase in household consumption of products and services under the same situation.

3. In the process of economic and social development, if there is a general trend of [(P1-P0)/P0>(H1-H0)/H0], it means that Wagner's law is established.

4. For the budget constraint curve B0B'0, point S0 means the government has not used up all resources to provide social welfare, and point S1 means it has spent more than it can cover. For the budget constraint curve B1B'1, both S0 and S1 mean that the government fail to reach its full potential in the case of providing social welfare. And for any budget constraint curve, S2 means the government has gone too far and neglected its financial capacity.

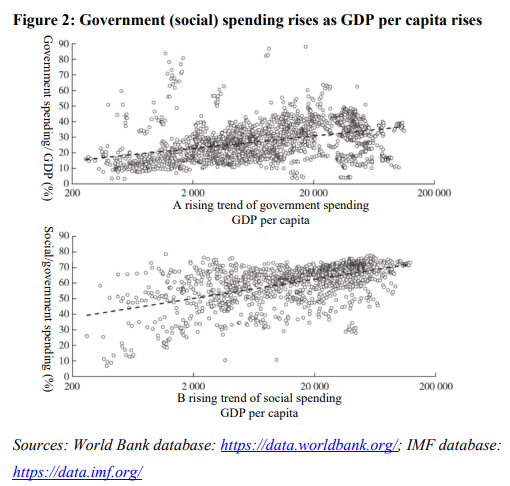

We can further illustrate Wagner’s Law statistically using cross-country time series data from the World Bank and IMF databases (Figure 2).

According to Wagner's Law, with the increase of per capita GDP, the proportion of government expenditure to GDP generally shows an increasing trend (Figure 2A). However, the content of this government expenditure is too broad. There are ten items in total, namely (1) general public service expenditure; (2) defense expenditure; (3) expenditure on public order and security; (4) expenditure on economic affairs; (5) expenditure on environmental protection; (6) expenditure on housing and community welfare facilities; (7) health expenditure; (8) recreation, culture and religion expenditure; (9) expenditure on education; (10) social protection expenditure.

The latter five items are related to social welfare. The proportion of expenditure on these five items to total government expenditure also shows a trend of increasing with per capita GDP growth (Figure 2B).

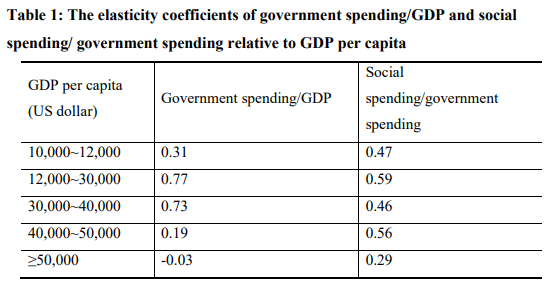

Next, we explored the features of the rise of government spending/GDP and social spending/government spending in different stages of economic development. Economies were divided into 5 groups based on the levels of GDP per capita, which do not exactly correspond to the income classification criteria of the World Bank, but used the criteria as a reference (Hamadeh et al., 2021).

Of the five groups, a GDP per capita of 10,000~ 12,000 US dollars represents a country’s development stage of transitioning from middle-income to high-income; 12,000~30,000 US dollars stands for the stage of moving towards a moderately-developed country after passing the high-income threshold; 30,000~40,000 US dollars refers to the stage of approaching the average income of high-income countries; 40,000~50,000 US dollars and beyond is the stage featuring very high-income level.

Based on the data from the World Bank and IMF, we built an unbalanced panel data model based on fixed effects, using the ratio of government spending to GDP and the ratio of government social spending to total government spending as response variables and the logarithm of GDP per capita as an explanatory variable to estimate the relationship between the two ratios (percentage) and GDP per capita. The estimated coefficients were divided by 10 to obtain the elasticity coefficients of the two ratios relative to the growth of GDP per capita (Table 1).

First, in terms of the relationship between stage of development and the ratio of government spending to GDP. The coefficients in the 2nd column in Table 1 show the percentage point increase in government spending/GDP for each 10% rise in GDP per capita. Except for the groups of $40,000~50,000 and ≥$50,000, other groups’ coefficients are statistically significant at 1% level. Next, as for the relationship between the stage of development and the ratio of social spending to government spending. The 3rd column demonstrates the percentage point increase in social spending/government spending for each 10% rise in GDP per capita. Except for the groups of $40,000~50,000, other groups’ coefficients are statistically significant at least at 10% level.

As shown both in Figure 2 and Table 1, in addition to the general trend revealed by the Wagner's Law, another special feature was found in one particular stage of development. That is, when a nation’s GDP per capita ranges from 12,000 to 30,000 US dollars, the growth of government spending/GDP and social spending/government spending both outpaced those in other ranges. Cross-country data analysis, country-specific studies or China’s reality all demonstrate that when the GDP per capita is in the range of $12.000~30,000, the country usually just passes the high-income threshold, and begins to strive to become a moderately-developed country and consolidate the status.

Accordingly, countries that fall into the income range of 12,000~30,000 US dollars tend to face the same development challenges.

1. In the process of coordinating economic growth and social development as well as narrowing the gap between actual development and modernization goal, there is an urgent need to make up for the weakness in people’s livelihood, especially to narrow the income gap through redistribution measures.

2. After the period of high-speed growth ends, new growth engines are needed. In this stage, new sources of productivity can only be found through the mechanism of creative destruction, or the entry and exit of enterprises. Embracing this mechanism without hurting the basic livelihood of workers requires improving the level and coverage of social protection.

3. As population ageing accelerates and deepens, demand-side factors, especially household consumption, will restrain economic growth more, which will become the new normal. In response, institutionalized social welfare and stronger measures to improve people’s livelihood are needed so as to keep economic growth within an appropriate range through better household consumption capacity and propensity.

According to the 14th Five-Year Plan and the Long-Range Objectives through the Year 2035, China is expected to become a high-income country by 2025, and a moderately-developed country by 2035. If the criteria for achieving the two goals are based on the cross-country and country-specific analyses, the high income threshold defined by the World Bank, i.e., GDP per capita exceeding $12,695, can be taken as the first goal, and joining the medium income group of high-income countries, i.e., $23,000~40,000 GDP per capita (the simple average is $30,000), as the second goal. It can be seen that China’s development stage in the next 10~20 years falls right into the income range of $12,000~30,000.

If Wagner's Law is a general law with universality, based on China’s reality, we can refer to the process of raising GDP per capita from $12,000 to $30,000 as the "Wagner acceleration period", during which social welfare spending should increase significantly.

IV. INCREASING FUNDS FOR SOCIAL WELFARE SPENDING

If Wagner's law is a general law that applies to most countries and Wagner's acceleration period is a special law that applies to countries at a particular stage of development, statistically it is possible to create a model that can roughly reveal the level of social welfare spending an economy should have in relation to the level of GDP per capita. Although this paper does not aim to develop such a model, the descriptive statistics show that for China, the ratio of government spending to GDP and the ratio of social spending to government spending are both low relative to its stage of development.

To further analyze the question, we selected other economies with GDP per capita between $12,000 and $30,000 in the unbalanced panel data as the reference group, calculated the arithmetic average of the corresponding indicators, and compared them with the actual level of China. The results show that the share of Chinese government expenditure in GDP in 2020 is 33.9%, while the average of the reference group is 40.4%; the share of Chinese government social expenditure in total government expenditure is 52.4%, while the average of the reference group is 62.0% (Wang Dehua and Li Bingbing, 2022).

It can be seen that whether from the perspective of following the general law or responding to the pressing challenges of its own, in the coming 10~20 years, China needs to substantially increase public social spending, i.e. social welfare spending, to make up for the large shortfall.

Whether in the policy-making process or academic research at home and abroad, the necessity to expand public spending and the sustainability of fiscal capacity have become a much-discussed topic. In recent years, especially in response to the pandemic-induced shocks, countries tend to reject fiscal austerity and expand public spending to improve social welfare (Cai Fang, 2022). With a growing consensus on the necessity of increasing public spending, more discussions have been focused on the feasibility issue of “where the money comes from”. In the field of economics, the discussion is centered on whether governments need to expand budget deficits or maintain high debt ratios.

In these discussions, three are three types of views that are influential and highly relevant. They can be summarized as follows in the descending order of radicalness against conservative ideas.

The first type of view comes from Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). The representative figure and champion of the theory is Stephanie Kelton, who believes that the level of government debt and budget deficit is not a problem for countries that issue sovereign currencies. As long as the bottom line of not having high inflation is held, governments can create money with its own credit to pay for necessary public services and public investments (Kelton, 2020).

The second type of view can be summarized as “the idea of low cost of debt”. Olivier Blanchard found that when risk-free interest rates remaining below economic growth rates (r<g) is a norm rather than an exception, the way to judge the sustainability of debt and fiscal balance, as well as the “red line” for the current government debt and deficit levels, have changed significantly. The policy implications are that fiscal policy should be understood and introduced from the standpoint of the necessity for governments to fulfill their role instead of restraints on government’s fiscal capacity (Blanchard, 2019).

The third type of view can be summed up as “the idea of expanding the denominator”. According to Joseph Stiglitz, there are two ways to keep debt ratio at a sustainable level: one is reducing the numerator through austerity and the other is expanding the denominator through investment to boost economic growth. He argued that the former path was proven to be a failure by the EU practice after the global financial crisis, while the latter path was proven to be successful by the US practice after World War II (Stiglitz, 2021).

In essence, as long as the aggregate output, productivity, and per capita income are increasing, social spending that aims to improve people’s livelihood is necessary, and should and can rise as well. In particular, social welfare spending is non-productive and most of it is an investment in people, which can be regarded an investment for the future.

Based on the current trend, among the legacies of human kinds for the next generations, it is not productive capital but human and natural capital that is in shortage. If we use the comparison between the beginning and end of a given period of time to represent intergenerational relation, we can observe the changes in the capital stock in various forms during this period, or the legacies passed on from one generation to the next. A study that includes data from 140 countries shows that between 1992 and 2014, per capita ownership of productive capital doubled; human capital increased by 13%, while natural capital decreased by 40% (cited in Shafik, 2021, pp. 150-151).

As can be seen, the rise of social welfare spending means that the government steps in to turn productive capital with diminishing returns into human capital with increasing returns. The move is productive and sustainable, which underscores the alignment of ends and means of economic development.

Adequate funding for social welfare spending relies on increasing growth, productivity, and per capita income. As China is in the "Wagner acceleration period", to sharply raise social welfare spending and its share in GDP, it should depend on the growth potential (supply side) and the capacity to unlock the potential (demand side).

According to the estimate by Li Xuesong and Lu Yang (see China Development Research Foundation, 2022, Chapter 3), the potential GDP per capita growth projected between 2021 and 2035 under medium and high scenarios is 4.80% and 5.15% respectively. According to World Bank data, the arithmetic average of real GDP per capita growth for countries and regions in the Wagner acceleration period is only 1.21% from 2006 to 2019, suggesting that China has a foundation to significantly increase social welfare spending when passing the interval.

Meanwhile, it should be noted that China’s economic growth faces two major challenges due to the early arrival of the demographic turning point. First, the accelerated decline in working-age population and increase in the population’s dependency ratio will undercut the estimated potential growth rate. The way forward is to step up reforms and strive for results of the medium scenario forecast by following the requirements of the high scenario forecast. To that end, the most pressing task is to improve productivity through reallocating resources at industrial and business levels and to replace traditional demographic dividend with new growth momentum. It is necessary to rely on “survival of the fittest” among market entities, while avoiding letting any individual to become a "loser", which requires stronger social protection at the national level.

Second, deepening ageing and negative population growth will make the demand side continue to constrain China’s economic growth. Based on international experience, especially Japan’s one when its population began to decline, it’s easy to see the real growth rate falls short of the potential growth rate in this period and thus a growth gap persists (Cai Fang, 2021). To stabilize and expand aggregate social demand, particularly household consumption, it is necessary to substantially improve redistribution and increase social welfare spending. By narrowing the gaps of income and basic public services supply, a stimulating effect on consumption is created to offset the constraining effect of demographic turning point on consumption.

V. CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The history of economic development around the world shows that building a welfare state is one of the many inevitable parts of development and a necessary task to realize modernization for any country. Different schools of theories on development will influence countries’ policy tendency for development goals and paths, thereby leading to different outcomes in welfare state building. Countries that have chosen different welfare policies and policy combinations have benefited or paid the price in practice.

However, there is still a statistical law that can represent most countries’ policy tendency, known as the Wagner’s Law, i.e., a nation’s government spending (especially social spending) as a percentage of GDP will rise as its GDP per capita increases, until it reaches a very high level of income and welfare to accomplish the task of building a welfare state.

If we apply this law to China’s development stage, China is now at the Wagner acceleration period with a window of opportunity for welfare state building. In pursuing the goals of becoming a moderately-developed country and modernization, China should choose a path towards welfare state with its own characteristics, yet it cannot avoid the basic requirements of welfare state building. Therefore, improving social welfare and promoting common prosperity are consistent with each other.

At the same time, significantly increasing the level of social protection, social welfare, and social cohesion is necessary to meet the challenges posed by an aging population to economic growth, and to stabilize and expand consumption demand by improving household income and income distribution. Given that splitting the pie better through public policy and social welfare has become a necessary condition for making a bigger pie, macroeconomic policy that maintains growth within an appropriate range should be closely coordinated with social policy that speeds up the building of social welfare system.

The 19th National Congress put forward seven “access” requirements of ensuring access to childcare, education, employment, housing, medical services, elderly care, and social assistance, basically covering all the basic public services and setting up a universal social welfare system. Thus the seven access also defines the key areas and priorities for building a welfare state with Chinese characteristics.

Next, we outline the targets for relevant areas from four aspects and try to illustrate the overall requirements of the seven “access”, reflecting the unity of the two principles of making the utmost effort and considering one’s financial capacity, and coordinating the requirements of improving the basic public service system and the objectives of welfare state building with the goals of supply-side structural reform.

Instead of expounding on the specific areas for the targets, we focus on proposing the basic principles and revealing the policy implications.

First, raising the birth rate to a more sustainable level. Whether from other countries’ experience that witnessed a rebound in birth rate after becoming highly developed, or from China’s unique fertility potential that still exists, better social welfare plays a decisive role in improving childbearing willingness and fertility rate by reducing the costs of childbearing and education, as well as breaking time and financial constraints for better career and family development.

Second, improving human capital from people’s whole life cycle. In the face of the new round of technological revolution and industrial revolution, as well as the serious challenges to growth posed by population ageing, the fundamental solution is to substantially enhance the quality of workforce by extending the years of schooling and improving education quality. Given that future workers have to compete with robots and AI for jobs, the accumulation of human capital should start from an early stage of their life and run across the whole life cycle of their career.

Third, realizing universal coverage of social security. The more adequate the protection given by the social welfare system for workers, the riper the conditions are for the mechanism of creative destruction to work to fully tap into the potential for improving productivity, which can promote high-quality development.

Fourth, upgrading the proactive employment policies. Employment is essential to people’s livelihood. Public services and a sound labor market system that aim to promote employment are part of the social welfare system. To implement upgraded proactive employment policies, we need to coordinate macroeconomic policy, public services for employment, legislation and enforcement of labor law, employers, etc., to create more and better job positions.

The article was first published in Comparative Studies, vol.3, 2022. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the authors. The views expressed herewith are the authors’ own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations.