Abstract: In this paper, the author discusses three basic facts about China’s capital flows and explores the complex reasons behind by offering two explanatory frameworks. The last part summarizes implications for China’s choice of monetary policy.

The pandemic prevention and control policy has restricted normal economic activities, putting considerable downward pressure on the Chinese economy. Given such policy, fiscal policy and monetary policy should be given more weight than usual. A consensus has been reached among economists at home on adopting fiscal stimulus such as providing subsidies and bailouts, as well as increasing infrastructure investment. But when it comes to monetary policy, opinions differ as to which tools should be applied amid a sluggish economy and the widening interest rate gap between China and the United States, whether there is a need to cut interest rates, and whether the authorities should intervene in the foreign exchange market and step up control over capital flows? This is what this article is going to discuss.

I. CAPITAL FLOWS: FUNDAMENTAL FACTS, MAIN PARTICIPANTS AND INSTITUTIONAL ENVIRONMENT

First, let's look at some basic facts of capital flows.

The calculation of China's capital flows uses two approaches. The official statistical approach measures capital flows under a narrow concept, excluding the capital flow relating to foreign exchange reserves; the other approach adopts a wider concept and includes errors and omissions in the calculation. As can be seen from Figure 1, the two approaches yield similar trajectories.

Before 2014, China had seen a surplus in the capital account, in addition to a trade surplus, for most of the time. After 2014, especially during 2014-2016, a large-scale net capital outflow was recorded. Although the outflow narrowed after 2016, the scale of outflow was larger than that of the inflow. That is to say, the pattern of capital flows, movement of foreign exchange reserves excluded, has fundamentally changed since 2014. Before 2014, China exercised continuous intervention in the foreign exchange market and the central bank bought a large amount of foreign currencies. From the perspective of the balance of payments, surplus in both the current account and the capital account can only be possible with a continuous purchase of foreign currency and accumulation of foreign reserves. Otherwise, it is impossible to realize surplus in both the non-reserve capital account and the current account. After 2014, sometimes foreign exchange reserves were sold, and sometimes there was no intervention at all, so we see a surplus in the current account and a deficit in the capital account.

Figure 1: The pattern of China’s capital flows has changed fundamentally since 2014

China’s short-term capital flows are dominated by other investments, and securities investment is gaining more weight. Capital flows fall into three categories, i.e. direct investment, portfolio investment and other investment. Other investment refers to capital flows under items such as bank deposits, loans, and trade credits between residents and non-residents. In China's case, it is other investment that dominates short-term capital flows, not portfolio investment or direct investment.

Figure 2: Other investment dominates China’s short-term capital flow

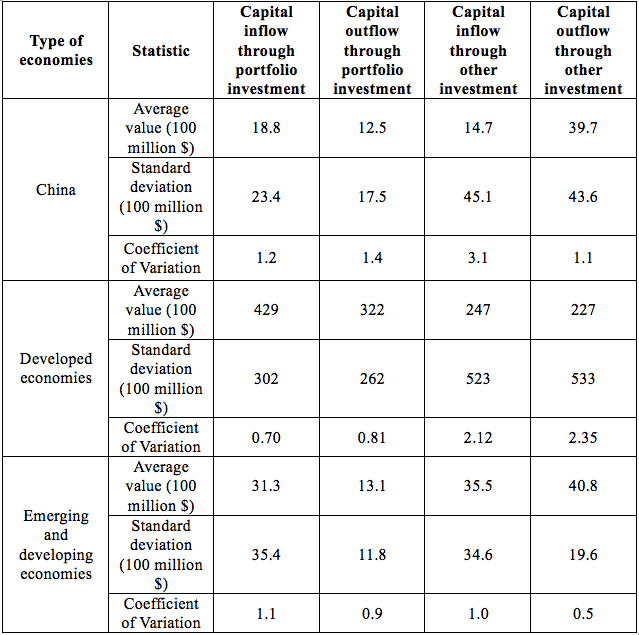

In addition, China's capital flows are highly volatile, much more so than those of developed countries and other emerging market countries (see Table 1).

Table 1: Comparing the patterns of short-term capital flows between China and other economies

Source: IMF

Secondly, there are four main types of participants in capital flows: first, foreign trade and foreign-funded enterprises, which are the most important market participants. Second, the wealthy group at home. Most of them engage in capital movement in the name of companies as individuals face numerous restrictions in this regard. Third, domestic and foreign financial institutions. For example, foreign funds and central banks can purchase Chinese bonds. Fourth, Chinese companies that looks for funding abroad, such as real estate developers and platform companies that issue bonds overseas.

Third, in terms of institutional environment, China has adopted a pipeline-style opening of capital account which means the household sector faces more restrictions when engaging in cross-border capital flows, while the corporate sector has more channels to participate. This also explains why China's capital flows are dominated by other investment, not like the case in developed countries where portfolio investment prevails. This is because in developed countries, financial institutions are more involved in capital flows on behalf of the household sector, while in China, the household sector, including financial institutions, is subject to many restrictions, and enterprises are relatively more flexible. Foreign trade and foreign-invested companies can engage in cross-border capital flows through other investment.

Despite the restrictions on the household sector and financial institutions, China is stepping up efforts to open up within certain areas and channels, including: allowing qualified domestic investors to buy B shares; launching programs such as Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII), Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor (QDII), Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII), Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect, Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect, Bond Connect and Mutual Recognition of Funds, etc.; supporting small, medium and micro high-tech enterprises to borrow external debts within a certain amount, and carrying out pilots such as Qualified Foreign Limited Partners (QFLP) and Qualified Domestic Limited Partners (QDLP).

II. EXPLANATORY FRAMEWORKS FOR CHINA’S CAPITAL FLOWS AND EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

The reasons behind capital flows are very complex. For economists, the difficulty in researching the issue lies in not only the large amount of influencing factors, but also the close connections among them. For example, both A and B can affect C, while A and B can affect each other, which complicates the analysis.

Factors that affect capital flows can be divided into endogenous variables and exogenous variables. Endogenous variables are variables that have strong linkage with other variables in a model, such as economic growth, interest rates, savings rates, investment rates, and wages and price levels, etc. Exogenous variables are variables that are relatively independent and not affected by changes in other economic variables. Exogenous variables can be divided into three categories: exogenous policy variables, such as exchange rate regimes, capital control policies, etc.; exogenous economic fundamentals, such as productivity, preferences, population, terms of trade, etc.; and exogenous short-term factors, mainly speculative factors that would result in frothy prices.

Based on the above four categories of determinants, there are two explanatory frameworks or two languages for capital flow analysis.

One framework analyzes the impact of RMB exchange rate expectations, interest rate spreads and domestic economic fundamentals among other factors on capital flows. Such analyses are often seen in the media, and many empirical studies are done. However, some more critical scholars do not agree with this approach, because these variables are closely related. From a mathematical point of view, endogenous variables cannot be explained by other endogenous variables, and can only be explained by exogenous variables. For example, for a system of equations, if X, Y, Z are set as endogenous variables, A, B, C exogenous variables, one cannot use Y and Z to explain X, but can only express X, Y, Z as functions of A, B, C. From the perspective of econometric analysis, X cannot be explained by Y and Z, because they are too closely related. Such regression results are not reliable.

This gives birth to the second analytical framework, which puts aside endogenous variables to look only at exogenous variables, that is, analyzes the impact of exogenous policy factors, economic fundamentals, and short-term factors on capital flows. This approach is theoretically cleaner and more reliable from an empirical perspective, but it also has limitations.

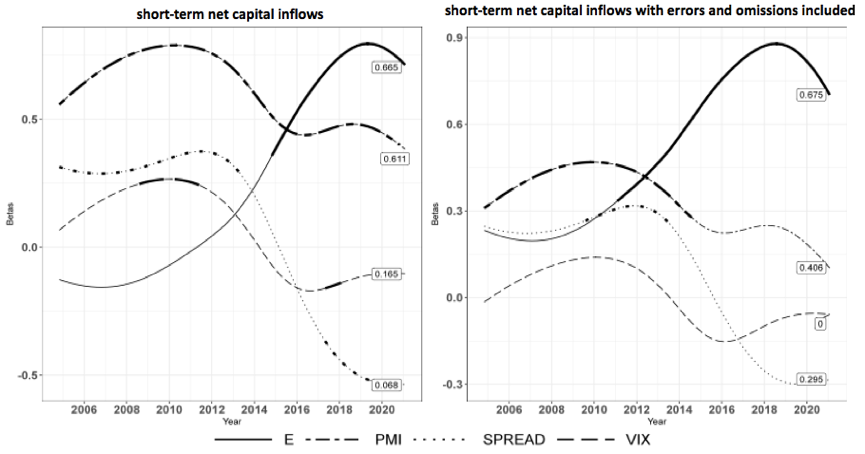

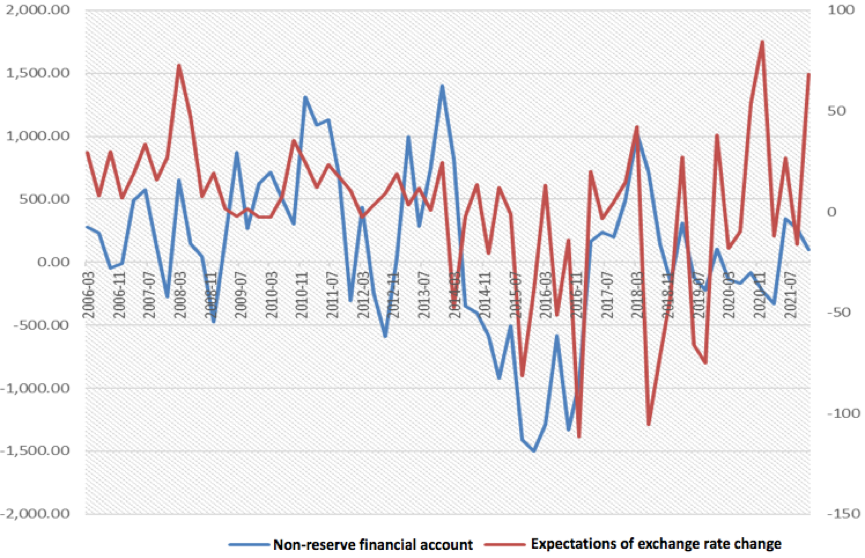

Capital flow is a hot topic that has been studied a lot. What is particularly interesting is that the conclusions of many studies are consistent: RMB exchange rate expectations and PMI index have a prominent impact on cross-border capital flows for most of the time; interest rate spread exerts an impact in some time periods; global financial market risk premium does not have a very significant impact from a long-term view.

In response to this conclusion, picky scholars argue that these variables are highly endogenous and the logic is not sound. However, these regressions are still useful because the correlation between these variables and capital flows can reveal which factors are more relevant for capital flows: Expectations for RMB appreciation and the PMI have a greater impact on capital flows; interest rate spreads have an impact during specific periods; the impact of VIX is insignificant.

Further analysis shows that exchange rate expectations are more correlated with the RMB exchange rate formation mechanism and the difference between the US and Chinese economic cycles; PMI is correlated with China’s macroeconomic policies and domestic and global economic cycles; the USD index is correlated with the RMB exchange rate formation mechanism, the US economic cycle, and global financial market risk; the interest rate spread is r correlated with the difference between economic cycles in the US and China; the VIX is correlated with global financial market risk.

Figure 3: The impact of RMB appreciation expectation, PMI, interest rate spread, and VIX on capital flows

III. THE IMPACT OF THE US ECONOMIC CYCLES, EXCHANGE RATE FORMATION MECHANISM, AND CHINA’S MACROECONOMIC POLICY

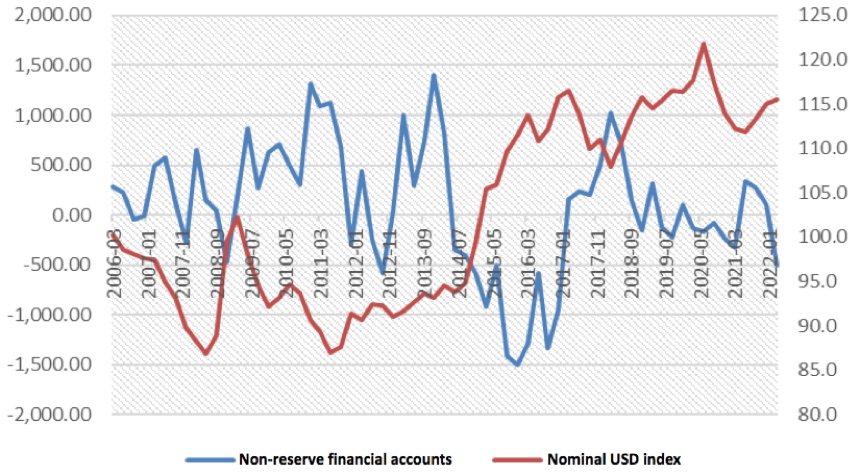

Changes in capital flows can be explained by the US economic cycle and the Fed’s policy changes, although the explanatory power varies over time. Exogenous variables that have impact on capital flows include the Fed's interest rate hikes and the rise in the dollar index. From 2012 to 2020, the dollar index experienced three upswings. Between 2012 and 2014, the dollar index climbed, while China saw net capital inflows and strong expectation for one-way RMB appreciation. The dollar index rose again throughout 2014-2016, accompanied by the largest net capital outflows in Chinese history. The dollar index entered a third round of upturn after 2017. During this period, China recorded net capital outflows, but the size of outflows had shrunk and stabilized.

Figure 4: The dollar index’s impact on China’s capital flows

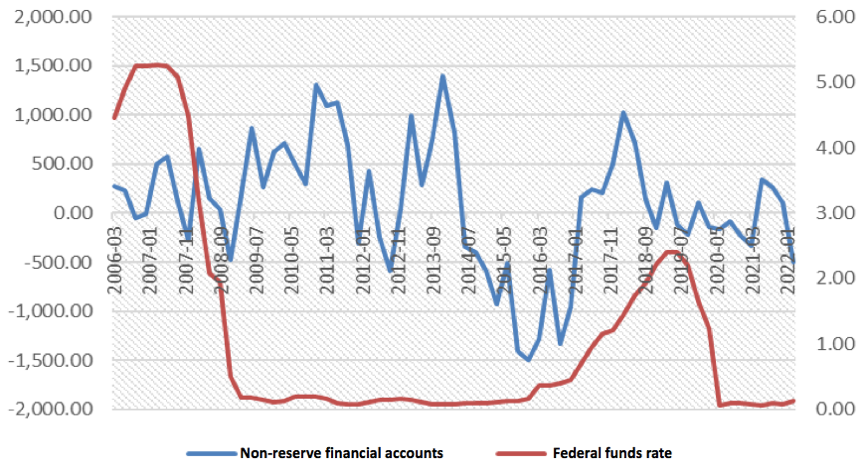

Let’s move on to the influence of the federal funds rate on capital flows. China’s capital was in net outflows during 2014-2016 when the market was expecting Fed rate hikes, but by the time the rate hikes actually began, net capital outflows had slowed dramatically.

Figure 5: The federal funds rate’s impact on China’s capital flows

Since 2005, China has implemented a RMB exchange rate formation mechanism that is based on market supply and demand, with reference to the exchange rate of a basket of currencies, and maintains the exchange rate within a reasonable range, which echoes the three regulatory targets of the PBC. However, the three targets are sometimes contradictory: if the exchange rate is based on market supply and demand, then it should rely entirely on them; if it is based entirely on the basket currencies, then it is not based on market supply and demand; if it is kept at a reasonable level, very often there is no way for perfect market clearing, since it not based on supply and demand. China adopted a compromise approach, and as a result, the market could not be fully cleared for a very long time. From the 2005 exchange rate reform to 2014, the RMB appreciated gradually for most of the time, with a two-year pause during the 2008 sub-prime crisis, followed by a period of devaluation.

Why is China's capital flow so massive? The fact that sustained expectations of one-way exchange rate movement might aggravate capital flow pressures is one of the most crucial reasons. Market participants will exchange RMB for USD if they believe the RMB will depreciate continually as a result of the central bank's policy. More speculative capital movements would result, exacerbating the volatility of capital flows.

Things changed after 2017 when the monetary authorities stopped purchasing and selling foreign currencies on the foreign exchange market. The RMB exchange rate became more market-based when the PBC phased out counter-cyclical factors in 2020, and expectations of one-way appreciation or depreciation of the RMB receded.

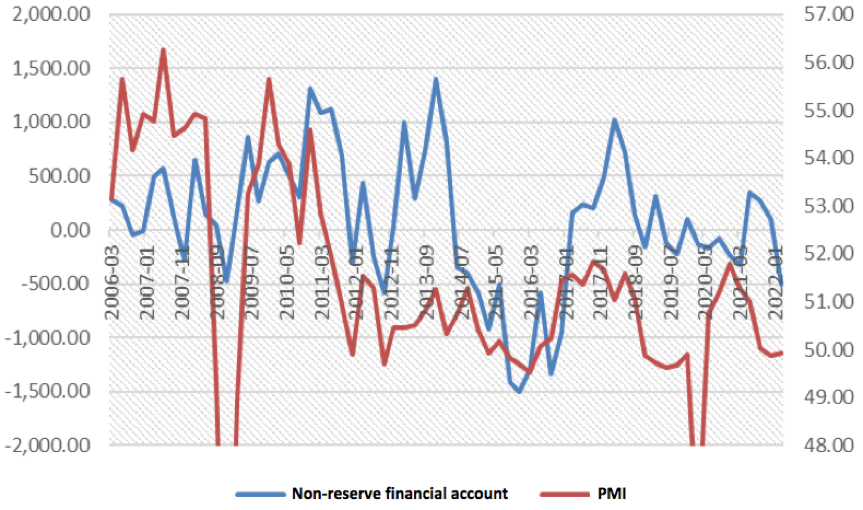

Figure 6: Continued expectations of one-way exchange rate movement will amplify capital flow pressures

Finally, let’s look at the impact of China’s macroeconomic policies, including domestic economic performance, on capital flows. China's capital flow and economic performance are closely related, both in the long run and in the short term, which has been confirmed by every empirical study. Foreign-invested firms, whose operating cash flow is highly tied to capital movements in the foreign exchange market, are the key participants in China's foreign exchange market, not financial institutions. When the economy is prospering, more money will flood in. Capitals tend to flow out when it underperforms.

Figure 7: PMI’s impact on China’s capital flow

IV. SUMMARY AND IMPLICATIONS

Based on the analysis above, we can draw the following conclusions:

1. Capital flows are influenced by many factors.

2. Changes in domestic and foreign economic cycles are often important triggers for changes in capital flows, especially changes in US economic cycle and the Fed’s policy shift.

3. The right exchange rate formation mechanism will be a stabilizer of capital flows, otherwise, it is an amplifier.

4. China’s macroeconomic policies are crucial to stabilizing economic fundamentals and capital flows.

The implications for China’s choice of monetary policy are as follows:

1. Changes in the US economic cycle and the Fed rate hikes put pressure on China's capital flows.

2. A flexible exchange rate regime is a stabilizer of capital flows. Try not to further introduce counter-cyclical factors or intervene in the foreign exchange market. Consider abandoning reference to a basket of currencies.

3. Maintaining domestic economic boom can help to alleviate the pressure of capital outflows. China shifted from net capital outflows to net inflows in 2016-2017 as the PMI rebounded despite the narrowing of the US-China interest rate spread.

4. Under a flexible exchange rate, interest rate cuts can boost the domestic economy and capital market confidence, thereby stabilizing capital flows.

This article is a speech made by the author at CF40 seminar on Chinese Economy and RMB Exchange Rate amid Global Financial Market Turmoil. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the author. The views expressed herewith are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations.