Abstract: In this article, the author proposed four policy suggestions that can boost China’s economic growth while avoiding fallouts. The first is to make full use of monetary policy and cut interest rates sharply. The second is to have fiscal tools to protect people’s basic livelihood, especially to subsidize businesses and low- and middle-income groups and support public good and quasi-public good infrastructure investment that lacks cash flow through government bonds issued at a discount and policy-based lending. The third is to implement regulatory reforms. The fourth is to stabilize the real estate market, revitalize the assets of real estate developers, and help them moderately deleverage.

New policies are needed to boost China’s economic vitality as the existing policies may fail to provide enough support to achieve the 5.5% growth target, and the challenges facing economic growth are huge and obvious.

I. BACKGROUND

Before discussing current problems facing the economy, I would like to take a look at the historical background of the Chinese economy. Positioning the current problems in a longer period of time may help us develop a better understanding and roll out better policy options.

There are two macroeconomic backgrounds, the transformation of the engines for industry growth and purchasing power.

The engine for industry growth is not necessarily the sector with the highest productivity or productivity growth, but the one that meets the most urgent needs and drives the economy forward.

For example, in the early stage of economic development, textile was not a sector with high productivity, but there was an urgent demand for it. In order to meet the needs for textile of the whole country and even the world, it was necessary to expand textile production and transport the products across the country and the world, which had boosted the development of a series of industries such as machinery and equipment, transportation, and road infrastructure.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the growth engine for China was capital-intensive industries. After entering the second decade, the engine has shifted to human-capital-intensive industries dominated by the service industry, which includes science, education, entertainment, healthcare, and business services, etc. The development of these industries caters to the most urgent needs of industrial and consumption upgrading, and has fostered the development of other industries, becoming the locomotive of economic growth. From the experience of high-income countries at similar stages of development, this transition is inevitable, and China is no exception.

However, the development of human-capital-intensive industries, especially the service industry, are fraught with difficulties. First, it is difficult to accumulate human capital; second, the industry has a low level of standardization, and suffers long investment cycles and high risks; third, the service industry often faces higher regulatory requirements, featuring high degree of regulation and insufficient market competition. Nonetheless, human-capital-intensive industries in China have witnessed rapid development over the past decade, with growth rates far outpacing those of other industries.

Apart from market demand, there are two important drivers of China’s economic development. One is the capital market, especially the overseas capital market. Many companies in China’s emerging industries achieved rapid growth by listing themselves in overseas markets. A lot of venture capital would look for promising projects in China and help the companies raise funds through overseas or domestic IPOs. This has become the main development model of companies in emerging industries like Taobao, JD.com, and Meituan. The other driver is Internet technology. The power of Internet technology lies not only in the technology itself, but also in its ability to help many companies bypass the regulation and achieve rapid growth in a short period, such as Ant Financial’s explosive development in providing personal financial services and micro loans to small businesses.

In terms of the shift in purchasing power engine, as China’s financial system is dominated by debt financing, purchasing power mainly comes from credit creation. In the 2000s, the business sector helped create credit, thereby generating deposits and purchasing power of the whole society. Of course, the contribution of external demand was also important. Entering the 2010s, the government and the household sector have replaced businesses to become the main creators of credit. In 2020, of China’s new broad credit, the coporate sector only accounted for 26% (versus 57% ten years ago), whereas households accounted for 24%, and government and platform companies comprised 50%.

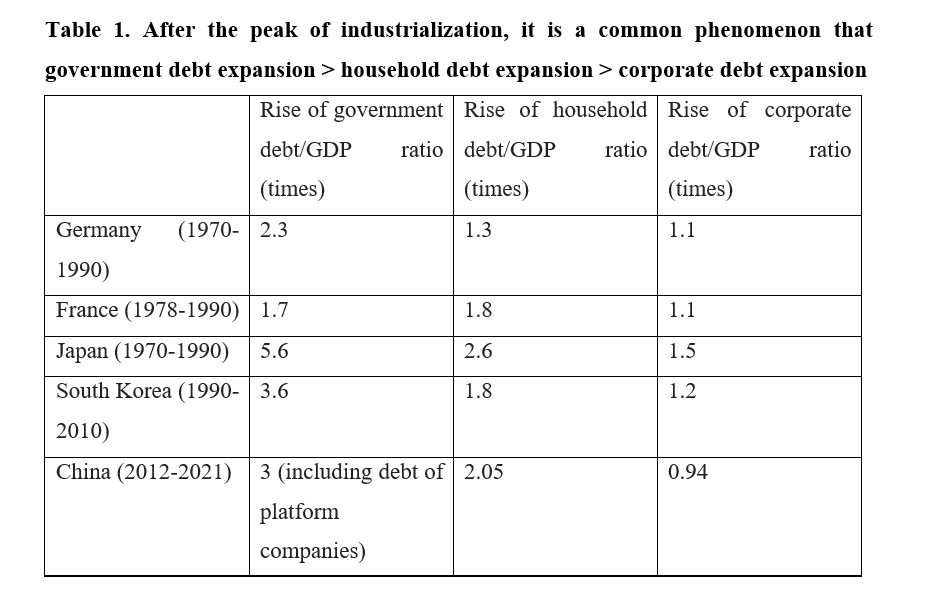

Many people raise concerns that when companies stop borrowing, and only households and government borrow, it will be detrimental to the optimal allocation of resources. In fact, China is not alone in seeing the decline of credit to the business sector and the rise of credit to the government and the household sector after the golden development period of capital-intensive industries came to an end. Similar phenomena have already been observed in high-income countries like Germany, France, Japan, and South Korea. The peak of Japan’s industrialization ended in the early 1970s. Between 1970 and 1990, Japan’s government debt-to-GDP ratio increased by 5.6 times, household debt-to-GDP ratio by 2.6 times, and corporate debt-to-GDP ratio by 1.5 times. Over the past decade, China’s government and platforms’ debt-to-GDP ratio rose by 3 times, household debt-to-GDP ratio by 2.05 times, and corporate debt-to-GDP ratio by 0.94 times.

II. SOURCES OF DOWNWARD PRESSURE ON CHINA’S ECONOMY

First, market contraction.

In terms of the industry growth engine, some emerging sectors related to Internet technology have been placed under regulation and face great uncertainty with regard to future policy direction. Some regulatory measures have severely hurt investments in these sectors. The decline of Chinese stocks listed overseas and Hong Kong stocks is flashing a warning sign for the future development of China’s emerging industries and China’s economic growth.

In terms of the engine for purchasing power growth, growth of credit to household and platform companies is impeded due to the decline in the real estate sector. The real estate sector creates mortgages on the one hand and local government financing vehicles (LGFVs)’ loans which are supported by revenues from land sales on the other hand. When the real estate sector is in trouble, credit growth will also encounter problems. So the calls for measures against credit collapse is not unfounded.

Second, lack of policy support.

The market needs the support of countercyclical policy to weather through the contraction.

In terms of fiscal policy, in 2022, China plans for budgetary expenditure growth at 8.4% and that of government funds at 22.3%, with an aggregate increase of 12.8%. While the 8.4% goal is undoubtedly within reach, the 22.3% target could be challenging. The level of budgetary expenditure depends heavily on local governments’ revenue from land sales, but such proceeds have slumped by 60-70% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2022 and could record negative growth for the whole year, which has direct negative impacts. If the actual growth of bugetary expenditure turns out to be way below the planned level, it would squeeze the room for countercyclical adjustment through fiscal policy.

In terms of monetary policy, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) has set the goals of “expanding the scale of newly added credit, ensuring that the growth of money supply and social financing keeps up with nominal economic growth, and stabilizing the macro leverage ratio.”

Quantitatively speaking, over the past five years, the geometric average growth of social financing in China was 15%, and the average growth of nominal GDP was 8.9%; in comparison, this year, China’s nominal GDP growth is projected at 8-9%, but its total social financing is expected to increase by only 10%, so it remains to be seen whether social financing expansion can keep up with economic growth. From the perspective of price levels, the policy rate has been reduced by 10 base points (bps), while the average repo rate implemented by depository financial institutions lowered by 5.6 bps during the 45 days after the policy rate reduction than in the 45 days before that, indicating a lack of willingness by the monetary authority to cut interest rates.

III. NEW ECONOMIC POLICIES

Is there any policy that can stimulate growth without negative aftereffects?

The answer is yes—and China has a lot of room for that.

First is to fully leverage interest rate policy and slash the rate. That could improve business and household balance sheets while boosting credit and total purchasing power. We have compared two methods to stimulate the economy: one is to cut the interest rate while reducing reliance on LGFVs; the other is the opposite, relying more on investment by LGFVs with no rate cuts. Our results show that the first can reduce leverage and increase the proportion of private investment while achieving economic growth.

There is a popular view that “rate cuts are useless”. However, there has yet to be any solid ground for such a strong judgment, given that interest rate policy is a textbook instrument that is being used widely across the world and playing an important role.

Some say that China is subject to strong soft budget constraint, with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) quite numb to interest rate adjustments. Then, what about the private and household sectors? What about the stock market? It’s beyond doubt that lower interest rates can help improve the balance sheets of these sectors, while we could resort to credit rationing in SOEs’ case.

Second, fiscal support can serve as the last line of defense. Fiscal sustainability, at the end of the day, depends on the sustainability and vitality of the economy and businesses, instead of budgetary balance. Against a pandemic-battered economy, China needs to step up fiscal expenditure and provide subsidies for the impacted businesses and middle- and low-income groups. It’s critical to resolve the hidden debt problems of LGFVs, but before stepping up restrictions on financing to these LGFVs, it is preferably to first help them repay existing debts and raise money in a more transparent, regulated manner. Public good and quasi-public good infrastructure investment projects running short of cashflows now account for a large proportion in total infrastructure investment in China, with a mismatch between fund supply and demand. Policymakers need to issue discounted government bonds and policy-based loans to boost such investment.

Third is regulatory reforms. For emerging sectors, regulators need to aim at resolving problems as they develop; they could strive to reduce administrative intervention in the market by enhancing necessary regulations in the first place, and establish new standards before phasing out outdated ones. They need to create sufficient space for the market’s trial-and error efforts so that businesses can grow and prosper. Any reform should start with regulators themselves: they should ask for the opinions of all stakeholders before rolling out new regulations, taking into account all possible consequences, and plan ahead. Accountability and correction mechanisms must be put in place as well to underpin sound regulatory policymaking. It would be desirable to press ahead with structural reforms when regulation is caught between conflicts of concepts and interests, but in case of conflicts that are too acute, it would also be wise to wait until the right timing.

Fourth, stabilizing the real estate market. China’s real estate sector face both immediate liquidity crunches, and an inflection point of the industry as well as deleveraging pressures in the medium to long run. China must work to break relevant bottlenecks so that the stumbling real estate sector does not disrupt its macroeconomic stability. The priority at the moment should be to help real estate developers gradually deleverage by mobilizing their overstocked assets. In addition, real estate developers should borrow money from legitimate sources instead of unqualified financing vehicles. Policymakers could also consider stepping up financial support for housing security and promote market-based mortgage rates.

This article is based on a speech made by the author at CF40 Annual Conference themed “Finance in Support of High-Quality Development: Reform and Outlook” with revisions. The views expressed herein are the author's own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations.