Abstract: The interest rate spread between Chinese and U.S. 10-year government bonds has almost fallen to its narrowest point. Even if the CNY weakens to some extent in the course of monetary policy easing, the "me-oriented" tone of macro policy should not be affected. The narrowing of the US-China interest rate differential shouldn’t prevent China from loosening its monetary policy.

The interest rate spread between China and the US has narrowed, but the RMB hasn’t depreciated – which goes against the interest rate parity. The main cause of this deviation is a shift in the relative risk situation in the US and Chinese financial markets, and also as a result of that, China still has much leeway in monetary policy.

Since the beginning of 2022, inflationary pressures in the US have continued to exceed expectations, causing the Fed to accelerate the withdrawal of the stimulating monetary policy and step up the pace of interest rate hikes, while China has continued to release policy signals for stable growth.

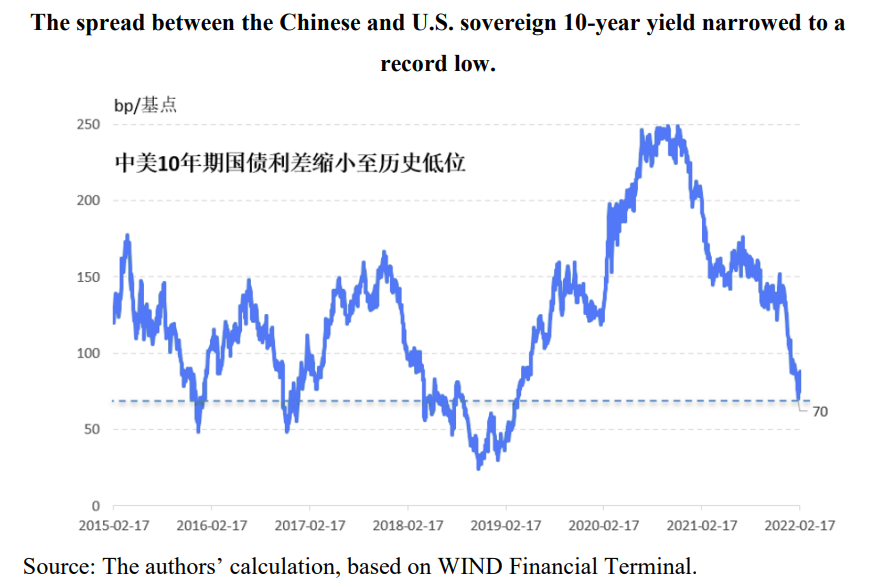

Against this backdrop, the spread between the Chinese and U.S. sovereign 10-year yield narrowed rapidly from 125 bps on the last trading day of 2021 to 88 bps on 18 February 2022; on 10 February, it contracted to 70 bps.

The spread fell to historic lows, only slightly higher than a few points since 2015. Looking at the direction of spread sliding, we’ll find that we’re having a similar experience to that of mid-December in 2015, the beginning of November in 2016, and mid-August in 2018.

In each of these periods, China had suffered from capital outflows and exchange rate depreciation. That's why people are concerned: will there be a risk of capital outflows as the China-US interest rate spread falls to a low level, and will this be a constraint on monetary policy easing in China?

I. EXAMINE THE EXCHANGE RATE DEVIATIONS THROUGH RISKS FACTORS

The spread between China and the US has shrunk to a historic low, but the RMB exchange rate has continued to rise, reaching new highs since 2018. How can we explain the RMB exchange rate's deviation from interest rate parity, and is this deviation sustainable?

The answers to this deviation generally are capital controls, forex market intervention, and risk factors.

The elasticity of the RMB exchange rate has risen in recent years and there is no evidence that forex market intervention has influenced the exchange rate. Meanwhile, financial openness has been wider since 2018 and has facilitated cross-border capital flows.

Both of the first two factors push the exchange rate towards interest rate parity. Therefore, the only way to understand the recent deviation of the RMB exchange rate from interest rate parity is to examine the risk factors.

II. “BAD HIKES” IN THE US AND RISING MARKET RISKS

Based on the reasons for the hikes, we can categorize the Fed's interest rate hikes into "good hikes" and "bad hikes".

A “good hike” is the one that happens when employment improves and the economy continues to grow. It’s a tightening policy, but as long as the basics continue to prosper, the financial market will rise. The Fed’s rate hikes in 2016 and 2017 were good hikes.

A "bad hike", on the other hand, is a reactive rate hike introduced based on poor fundamentals and upward inflationary pressures. A "bad" rate hike could bring adverse shocks to the US financial markets.

In contrast to the last round of "good hikes", this time the Fed is pushing for "bad hikes".

The Fed repeatedly stated in 2021 that inflation was "temporary," but later changed its mind, believing that inflation would continue for some time. To some extent, the Fed's guidance of market expectations failed.

At the same time, inflation in the US remains at record highs, with CPI rising at a 40-year high of 7.5% YoY in February 2022. Other important indicators, such as core PCE inflation and outlier-excluded PCE inflation, are both at all-time highs.

Among the factors driving up US inflation, supply chain and energy factors are easing, but food price, wages, and rents are on the rise.

Another important background for the "bad hikes" is the significant reduction in US growth expectations.

The IMF reduced the US 2022 growth forecast to 4% in January 2022, a significant 1.2 percentage point decrease from 5.2% in October 2021 and the largest reduction of any developed economy. The adjustment is being made as a result of the difficult delivery of the "Build Back Better" fiscal stimulus bill, the early exit from monetary easing, and ongoing supply chain disruptions.

Meanwhile, investment banks have cut their forecast for US growth in 2022, with the current market forecast averaging 3.8%. Goldman Sachs reduced its forecast to 3.2%, the sixth reduction since last July. Furthermore, according to the latest estimate from the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow model, US GDP growth will fall to an annualized QoQ rate of 0.1% in Q1 2022, compared to Goldman Sachs' forecast of 0.5%.

The market expects 4-6 rate hikes by the Fed in 2022, while as of Feb 11, the spread between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields has reduced to as low as 0.42 percentage points. That means the market expects that the Fed may continue to raise the interest rate at the risk of an inverted yield curve and economic recession to counter inflation pressure.

The U.S. is suffering ongoing inflation pressure with the Fed failing to guide market expectations and weakening growth momentum. Facing the challenges, the Fed had to introduce “bad” rate hikes at whatever costs, further adding to financial risks. As of January 2022, Shiller PE ratio for the S&P 500 had risen to 39.63, nearing the level in 2000 amid the dot-com bubble crisis. The Fed is finding itself on a narrow footbridge with its policy balance.

III. “GOOD” EASING IN CHINA PARING DOWN MARKET RISKS

In China, in comparison, macroeconomic policy and financial regulation tightening culminated in around September 2021, after which a series of adjustments and corrections have shored up global investor confidence.

Of particular note, the Central Economic Work Conference in December last year reiterated the country’s dedication to economic development, prioritizing economic stability while pursuing growth in 2022, and calling for measures conducive to economic stability and frontloaded policy endeavors as appropriate.

Addressing the fallacy of composition and division in China’s economic development in 2021, the Conference stressed the importance of properly understanding five policy focuses which were common prosperity, regulation of capital, primary product supply, financial risk control, and carbon reduction.

China has frontloaded its policy moves since the start of this year, pushing up newly added credits and social financing to a new height and issuing special bonds earlier than before. In comparison, no additional special bond was issued in January and February 2021, while this year as of February 8 new issuance had mounted to over 500 billion yuan, 35% of the quota of 1.46 trillion yuan for special debt this year set in advance by the Ministry of Finance.

At the current pace, special bonds issuance will be implemented much faster this year than in 2021. In addition, real estate regulation and control is marginally easing, while a series of policies for expanding domestic demand, stabilizing foreign trade and protecting market participants are also being gradually rolled out.

The easing policies under way or impending are “good” ones that help curb market risks, build expectation for growth, and stabilize investor confidence. The divergence in the level of risks between China and the U.S. can explain the deviation of the exchange rate movements from the interest rate parity.

The “bad” rate hikes in the U.S. and the “good” easing in China have increased the risks in the U.S. market while reducing those in China, respectively. That also explains a robust, if not stronger, RMB and corresponding capital flows while the spread between the two economies narrows.

Let’s look at the volatility index (VIX) for S&P 500 and the CBOE China ETF Volatility Index (VXFXI), which are used to depict the level of risks in the U.S. and Chinese financial markets, respectively. We choose to use VXFXI for a lack of comparable indicators to the VIX in mainland China, and using the HSI Volatility Index (VHSI) would lead to similar conclusions, too.

In terms of the monthly average, VXFXI peaked in September 2021 at 32.5, later falling by 4.1% to 31.2 in February 2022. During the same period, VIX rose from 19.8 to 23.0 by 16.1%. That means risk sentiments in the Chinese market have improved while those in the U.S. have worsened.

Accordingly, after September 2021, the two-way Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect has witnessed net fund inflows, showing that overseas institutions are stepping up investments in the A-share market and Chinese assets via various channels.

On the contrary, back in 2015 and 2016, the U.S. was having “good” rate hikes with moderate inflation and a brighter employment and growth picture, while China faced mounting financial risks.

During January and August 2015, the monthly average of VXFXI climbed up from 26.0 to 36.5 by as much as 40%, while VIX inched higher marginally by only 2%. In August 2015, the two countries recorded an average interest rate differential of as high as 130 basis points, a slight 37 basis points lower than in January that year, but the notable changes in the level of risk sentiments in China in contrast to the U.S. placed RMB under huge strains. Hence, back then risk factors also played an important role shaping the exchange rate movements.

From the perspective of the balance of payments, the interest rate parity explains changes in the exchange rate mainly from a cross-border capital flow point of view. But at the same time, the current account also plays a major part in the supply-demand relationship in the foreign exchange market. In 1H21, China maintained surprisingly strong exports, and the large surplus it reaped under its balance of payments pillared a strong RMB. Meanwhile, foreign exchange purchase by banks had a bigger share in China’s foreign-related revenue than that of foreign exchange sales by banks in foreign-related expenditures, indicating market expectations for a stronger RMB.

In addition, if we look at the capital and financial account, RMB’s global status is improving as an international reserve currency, and the Chinese bond market has been incorporated into leading international indexes like the MSCI index. These mid- and long-term factors are also playing a role. The rising demand of foreign institutions for investment in RMB assets has helped sustain capital inflow as well.

To sum up, the interest rate differential between China and the U.S. is not the major factor behind changes in the RMB exchange rate. Instead, it’s the non-spread factors that play the biggest part.

In 1H22, China’s trade surplus is expected to keep sustaining the supply-demand balance in its foreign exchange market. What has changed significantly is the level of risks in China and the U.S. since September 2021, with the U.S. market seeing a buildup of risks as a result of “bad” rate hikes while China becoming less risky with “good” easing policies that could even help stabilize the RMB’s exchange rate.

At the moment, the “comfort zone” for the two countries’ spread may be well below 80 basis points. From this point of view, China’s is enjoying a bigger space for monetary policy, with the RMB less responsive to spread fluctuations. Even if the currency weakens during monetary easing, China should still maintain policy independence. A narrowing spread between China and the U.S. should not interfere with China’s monetary easing. The country should further loosen its macroeconomic policies including monetary policy with more substantial moves to further strengthen market confidence and expectations.

This article was first published in Caijing. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the authors. The viewpoints herein are the authors’ own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations.