Abstract: China has set the goal for the GDP to grow about 5.5% this year. In this paper, the authors examined what this target means for the Chinese economy, and estimated how fast China’s infrastructure investment needs to grow in order to realize the target. The authors suggested that infrastructure investment should grow at 6%, and to achieve this goal, it is essential to increase budgetary expenditure for infrastructure investment.

On December 10, 2021, the Central Economic Work Conference proposed that the priority for 2022 should be stabilizing the economy. All regions and departments should take active measures to achieve this goal. With the blow of the covid pandemic and the external environment becoming more complicated and uncertain, the Chinese economy is facing triple pressures of demand contraction, supply shocks, and weakening expectations. There will be more difficulties and challenges to overcome in order to achieve stable growth. The meeting also called on all sides to take the initiative and launch policies conducive to economic stability. Obviously, the Chinese government has taken stabilizing growth as the primary goal of its macro policy in 2022.

I. GDP GROWTH TARGET FOR 2022

The market generally believes the GDP growth in 2022 should be 5.5%.

In the case of China, due to its distinctive system, China's expansionary fiscal policy is carried out by increasing fiscal expenditure to support infrastructure investment, and stimulating private investment through the crowding-in effect created by the increased investment. This is what happened during the Asian financial crisis in 1998 as well as the global financial crisis in 2009.

In this article, we try to answer a key question, i.e. how much infrastructure investment is needed to achieve the growth target of 5.5%, and how to ensure that sufficient funds are raised to support the investment?

With the growth target set at 5.5%, first we have to estimate the contribution of consumption and net exports on GDP growth (by percentage points). The next is to determine the rate of investment growth needed to achieve the growth target. Within investment, the growth of manufacturing and real estate investment is not directly controlled by the government. Therefore, only after figuring out the growth rates of investment in these two sectors can we estimate how fast the growth of infrastructure investment should be.

II. FIXED ASSET INVESTMENT NEEDED TO ACHIEVE THE 5.5% GROWTH TARGET

Based on the GDP in 2020 calculated with the expenditure approach and contribution ratios of consumption, investment (capital formation), and import and export to economic growth released by the National Bureau of Statistics in 2021, it can be inferred that the shares of consumption, investment, and import and export in GDP are 55.5%, 40.7%, and 3.8% respectively in 2021 .

For the whole year of 2021, consumption, investment and net export drive GDP growth by 5.3, 1.1 and 1.7 percentage points respectively, with ratios of contribution being 65.4%, 13.7% and 20.9% .

1. Expected consumption growth in 2022

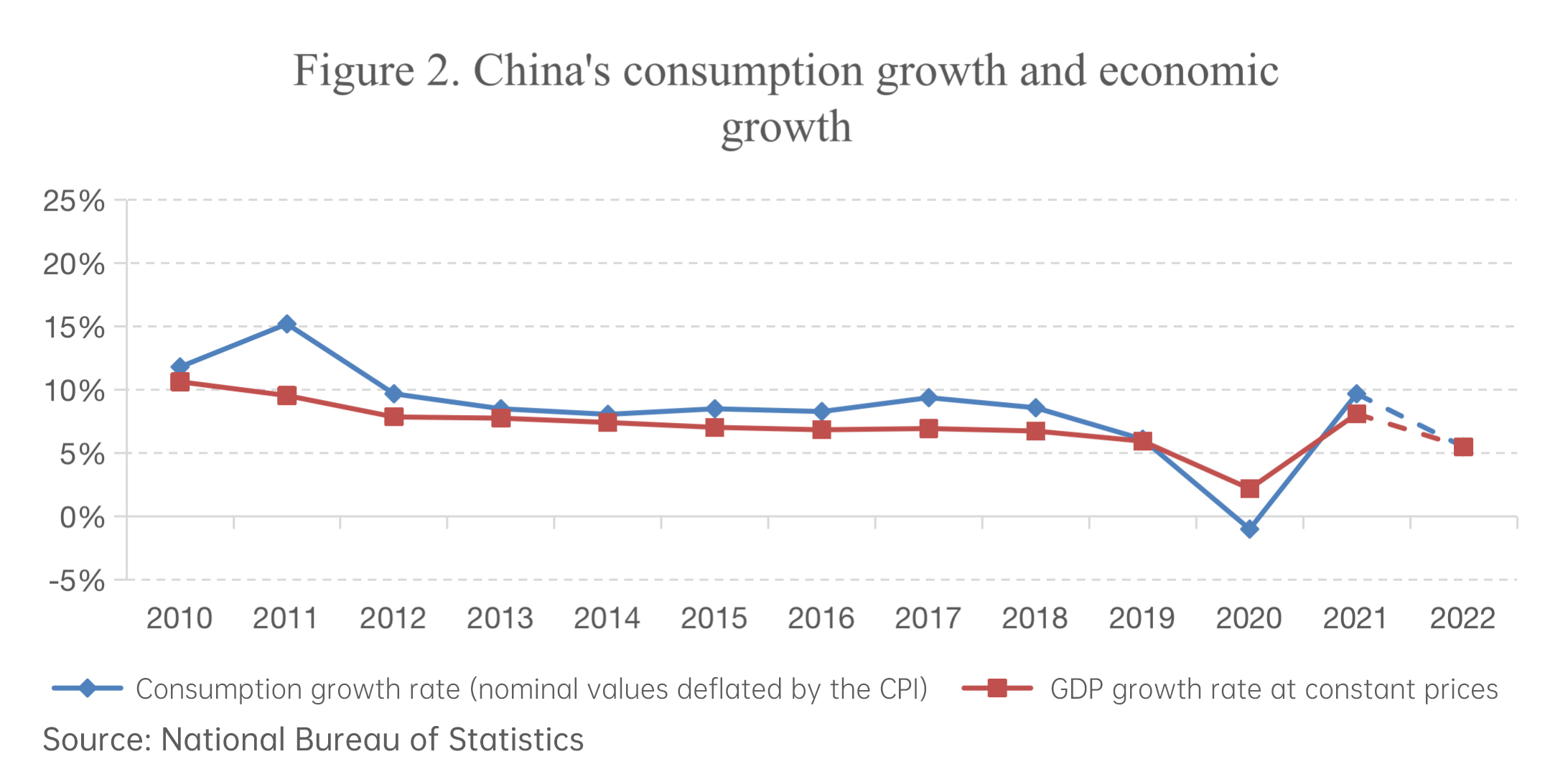

As can be seen from Figure 2 , since 2010, the gap between China's consumption growth rate and GDP growth rate has been narrowing, and consumption has played a less important role in driving GDP growth. Considering that since 2019, the factors affecting consumer decision-making such as inflation and interest rates have not changed much, we assume that the relationship between consumption growth and economic growth in 2022 is similar to that in 2019. Let’s assume that consumption growth will be around 5.5% in 2022.

Note: Dashed lines indicate expected values

2. Expected net export growth in 2022

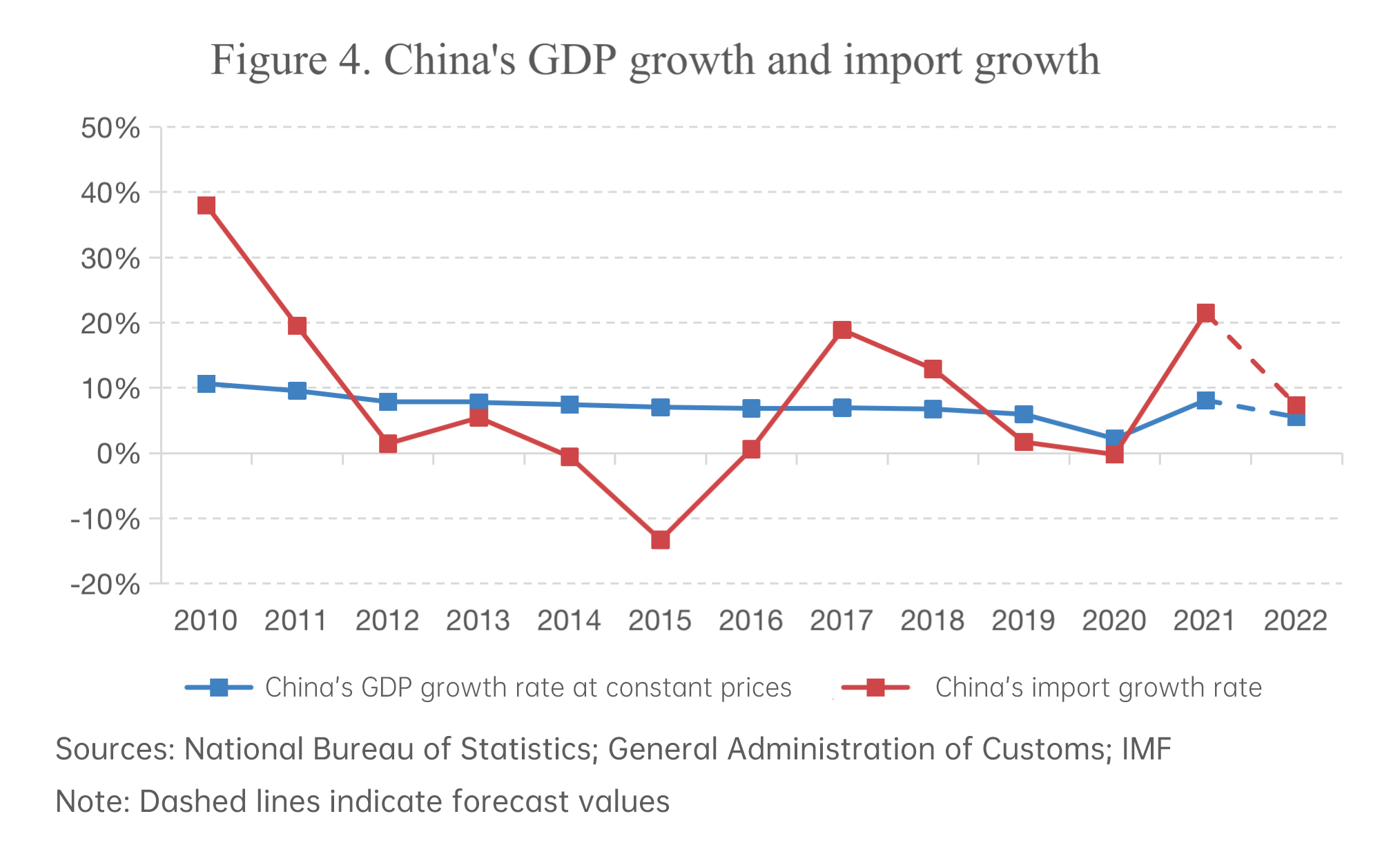

As can be seen from Figure 3, the growth rate of China's export since 2017 is correlated with the growth rate of the US economy. Considering that export growth in 2018 and 2019 is relatively stable, and with the global economy slowing down, we can assume that China's export growth in 2022 will be around the two-year average of 6.0%, and the total export will reach 23.04 trillion yuan. As can be seen from Figure 4, after 2017, China's import growth rate is consistent with GDP growth rate. Similar to the treatment of export, we use the average of 2018 and 2019 numbers to predict China's import growth rate in 2022, the estimated growth is 7.29%, and the total value of import would reach 18.64 trillion yuan. The expected net export in 2022 is 4.41 trillion yuan, and the number is 4.36 trillion in the previous year, meaning that the growth rate of China's net export in 2022 is about 1%. For this analysis, we would not consider shocks like the Ukraine crisis at the moment.

3. The rate at which fixed asset investment needs to grow in 2022

Knowing that consumption, investment (capital formation) and net exports respectively account for 55.5%, 40.7%, and 3.8% of GDP in 2021, we can get that the expected contribution of consumption and net export to GDP growth in 2022 would be 3.1 percentage points, and thus the contribution of capital formation to GDP growth should be 2.4 percentage points. This implies that capital formation should grow at 5.9% in 2022.

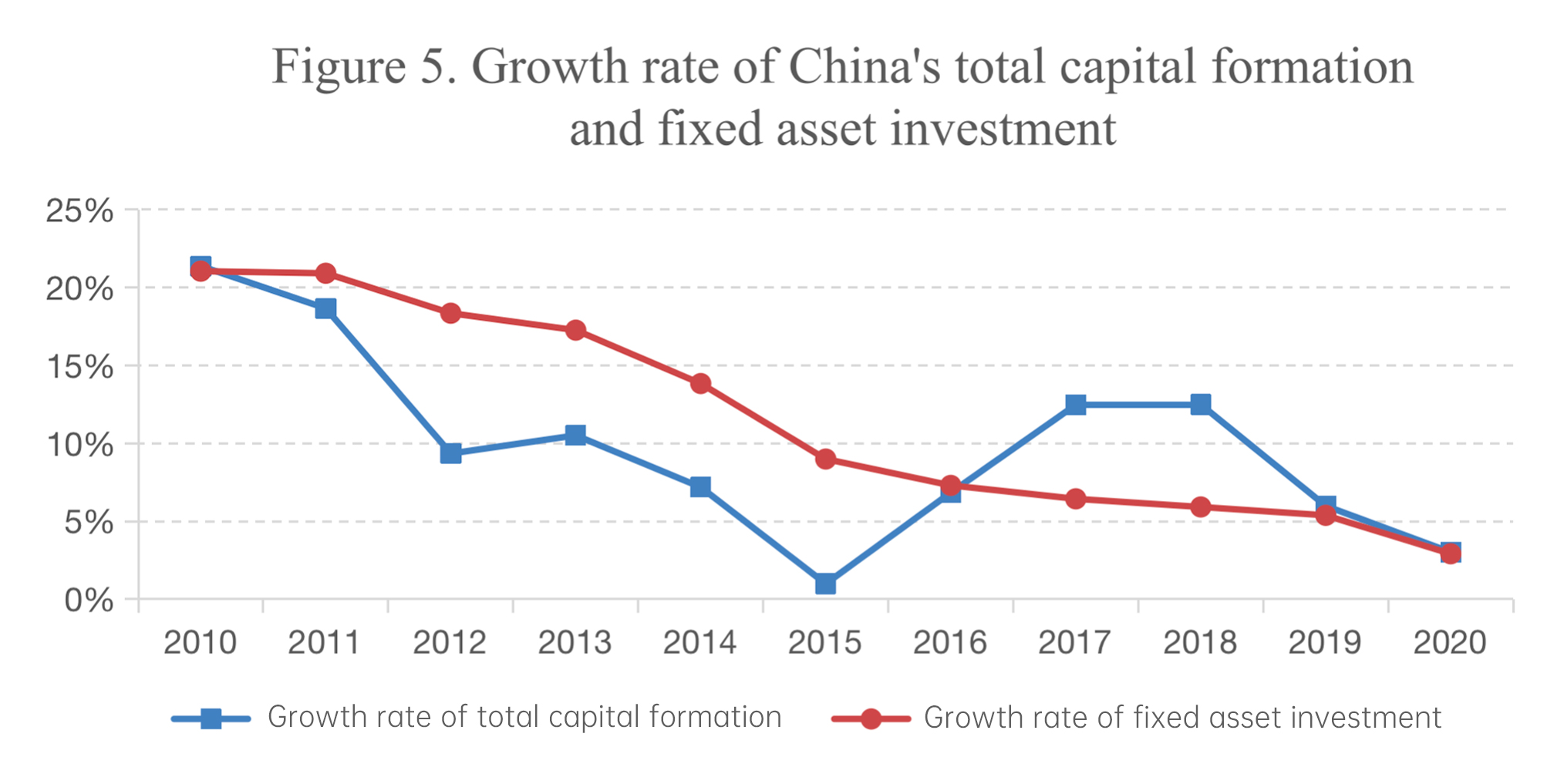

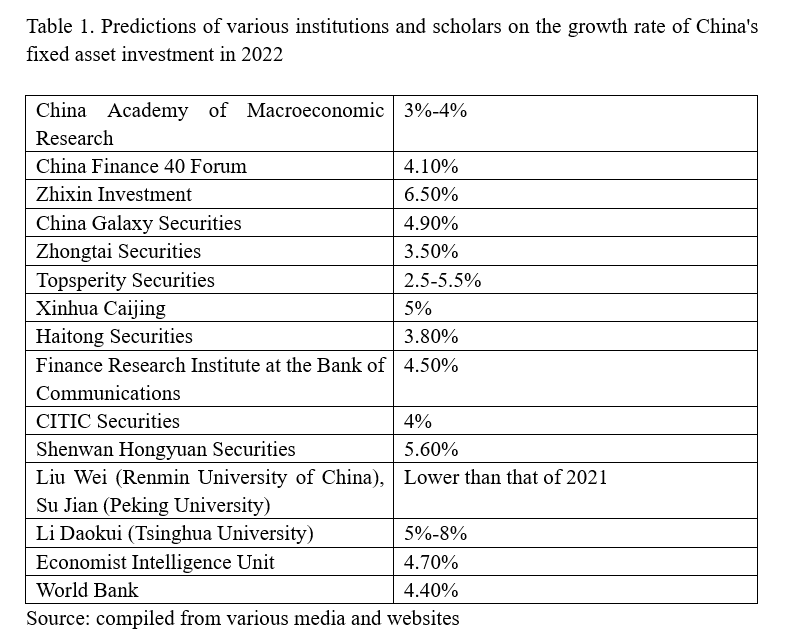

In order to determine the growth rate of infrastructure investment needed for realizing a GDP target of 5.5%, we need to shift from the concept of capital formation to the concept of fixed asset investment. According to historical data, in order to achieve annual GDP growth of 5.5%, the nominal growth rate of fixed asset investment should reach 5.7% .

III. THE GROWTH RATE OF INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT NEEDED FOR FIXED ASSET INVESTMENT TO GROW AT 5.7%

What growth rates can the three components of fixed asset investment sustain in 2022?

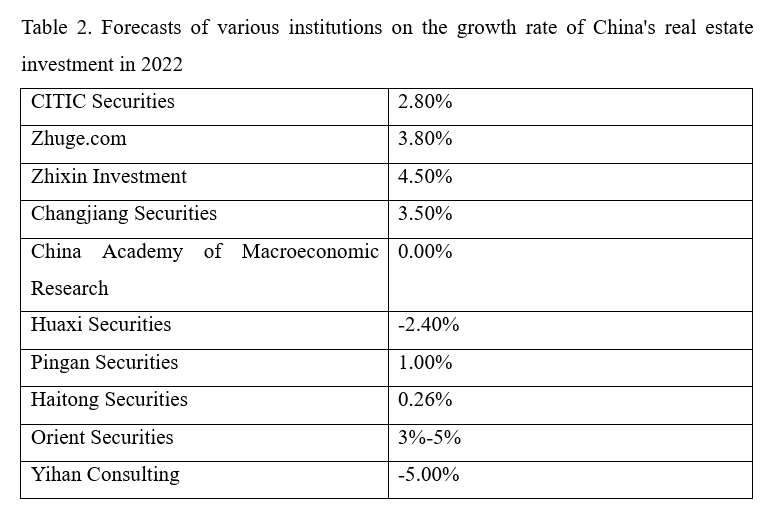

It’s natural to assume that while the government won’t significantly adjust its regulatory policy for the real estate sector in 2022, it is reluctant to see a sharp drop in housing prices or the growth of real estate investment. Let’s assume the growth rate of real estate investment is 4.0% taking into consideration factors such as government regulation and the construction of affordable housing. This rate is on the high end among many forecasts.

Table 2 shows the forecasts by various institutions for the growth rate of real estate investment in 2022. If proactive policies are implemented in 2022, it is possible to achieve a growth rate of 4.0% in real estate investment, which is slightly lower than the rate in 2021.

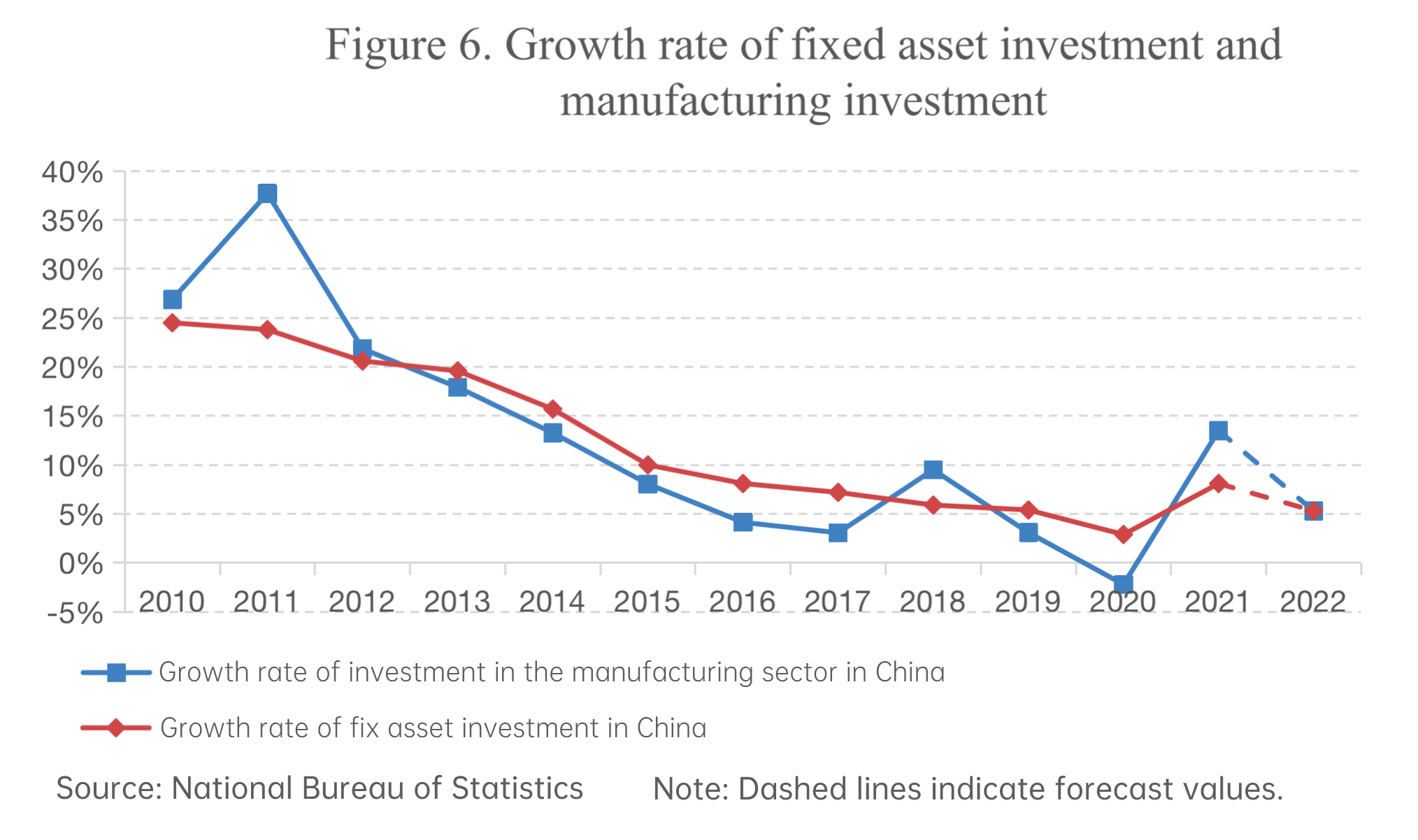

Second, estimate the growth rate of manufacturing investment. Given that the decline in export growth in 2022 may be relatively large, and the driving effect of infrastructure investment growth may not be obvious in 2022, manufacturing investment growth may be apparently lower than in 2021 unless special situations occur.

Historically, the growth rate of manufacturing investment has been relatively close to that of fixed asset investment due to its high proportion in the latter. Therefore, it can be assumed that the growth rate of manufacturing investment in 2022 will remain roughly the same as the growth rate of fixed asset investment, that is, 5.7%.

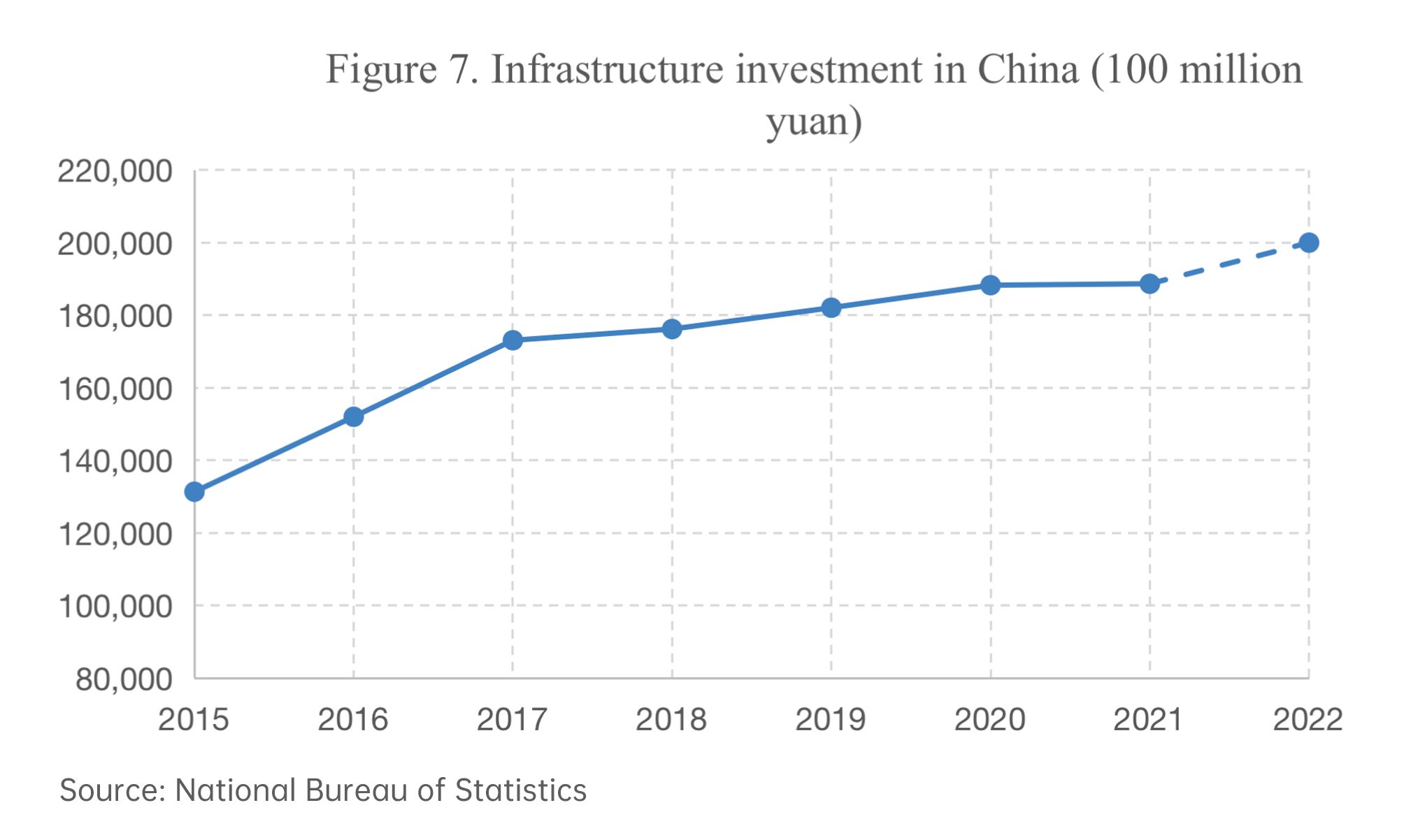

With the growth rate of real estate in 2022 assumed at 4.0%, that of manufacturing investment and other investment at 5.7%, and the proportion of manufacturing, infrastructure and real estate in fixed asset investment in 2021 known to be 42%, 33% and 25% respectively, the nominal growth rate of infrastructure investment needs to be 6.0% in order for fixed asset investment to grow at 5.7%.

The National Bureau of Statistics stopped publishing relevant data in 2017, but it could be inferred that infrastructure investment in 2021 is 18.87 trillion yuan. Therefore, if the growth rate of infrastructure investment in 2022 is 6.0%, the total amount of investment should be 20 trillion yuan.

IV. THE CHANGING TREND OF INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT IN RECENT YEARS

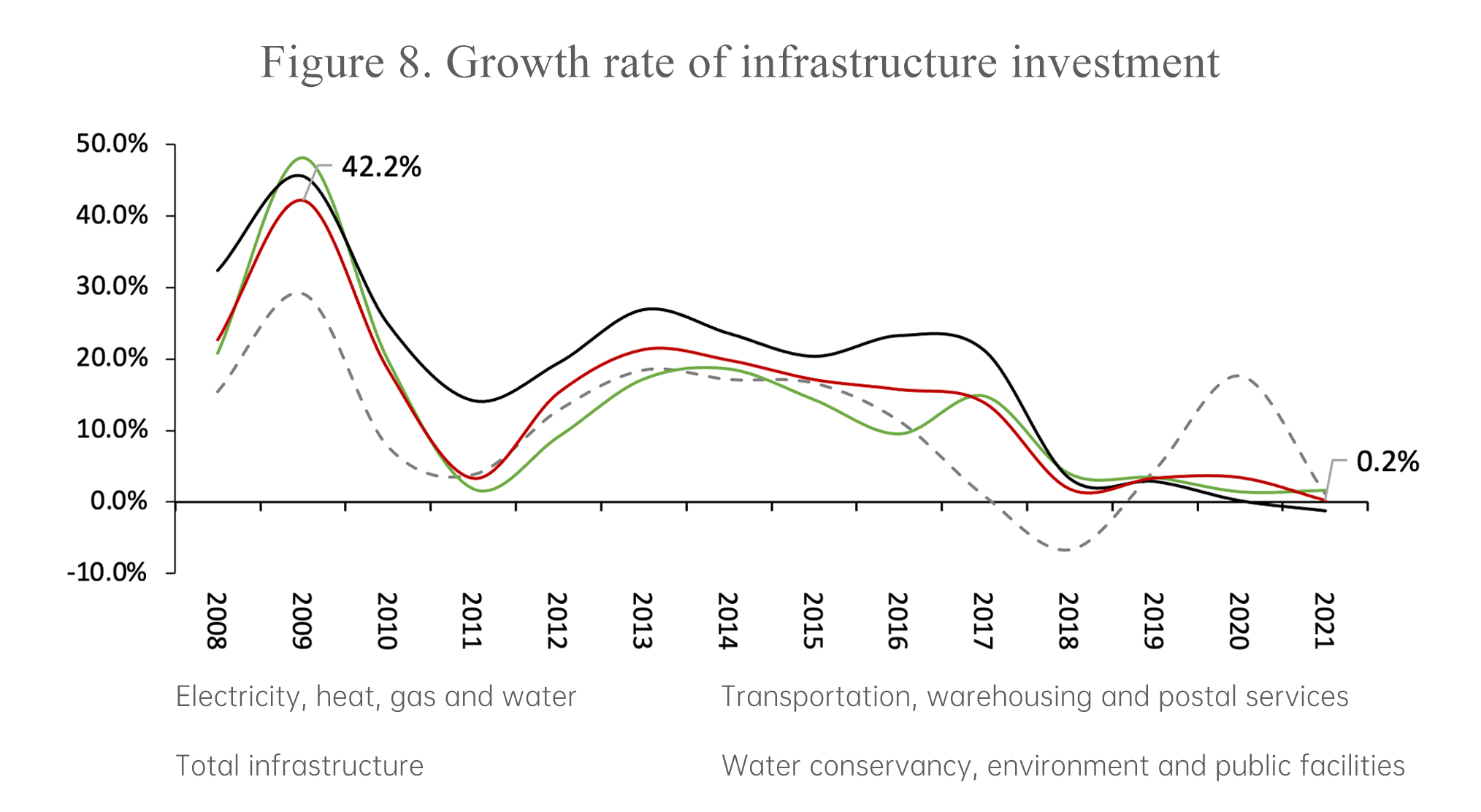

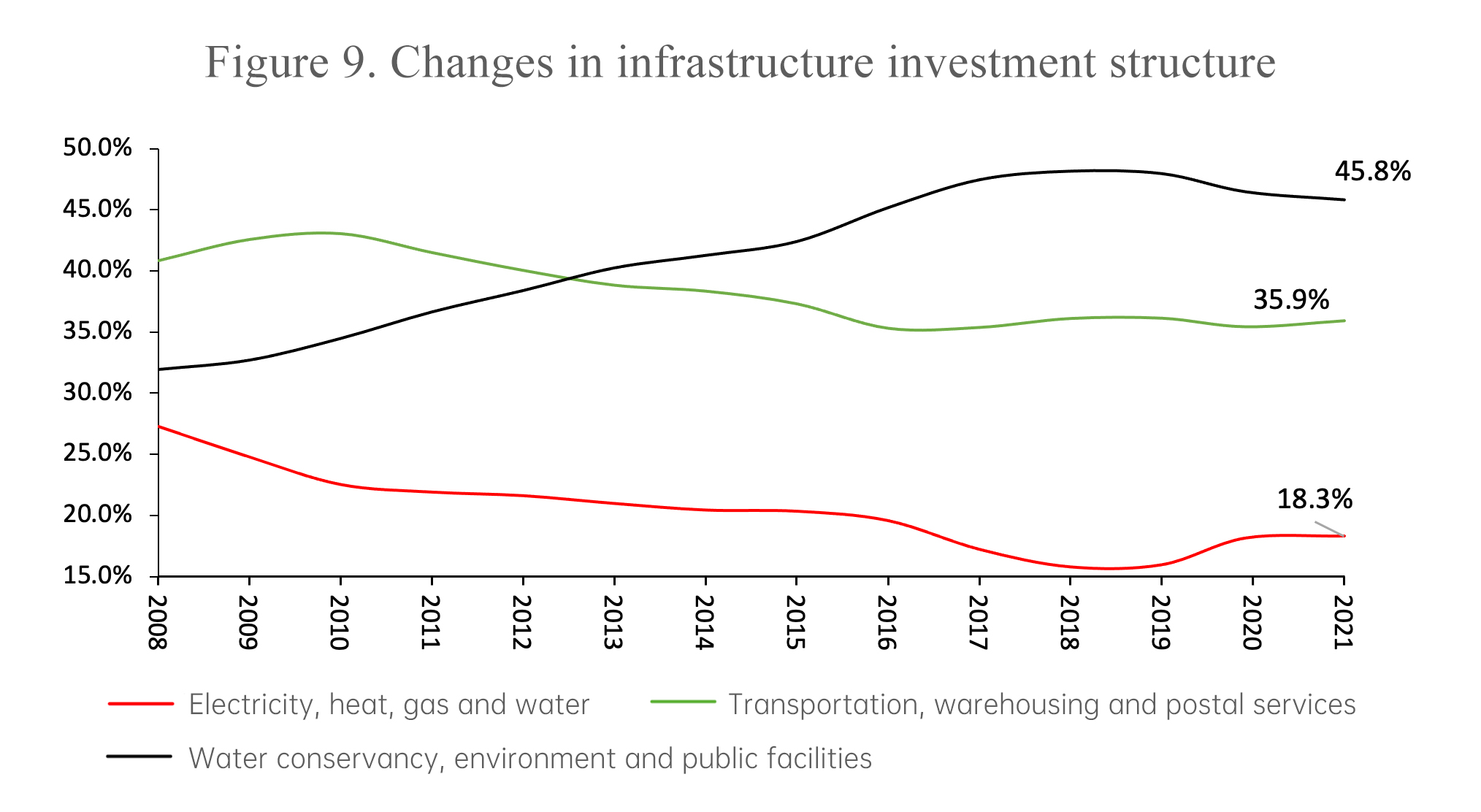

Infrastructure includes three major industries: 1) production and supply of electricity, heat, gas and water; 2) transportation, warehousing and postal services; 3) water conservancy, environment and public facilities management. Among these three major industries, investment in the third category has gradually gained a dominant position, accounting for 45.8% in the entire infrastructure sector in 2021, significantly higher than the other two industries.

Source: Wind

Source: Wind

While occupying a dominant position in infrastructure investment, the growth rate of investment in water conservancy, environment and public facilities has declined significantly since 2017, becoming the main cause of the sluggish growth of infrastructure investment in 2021.

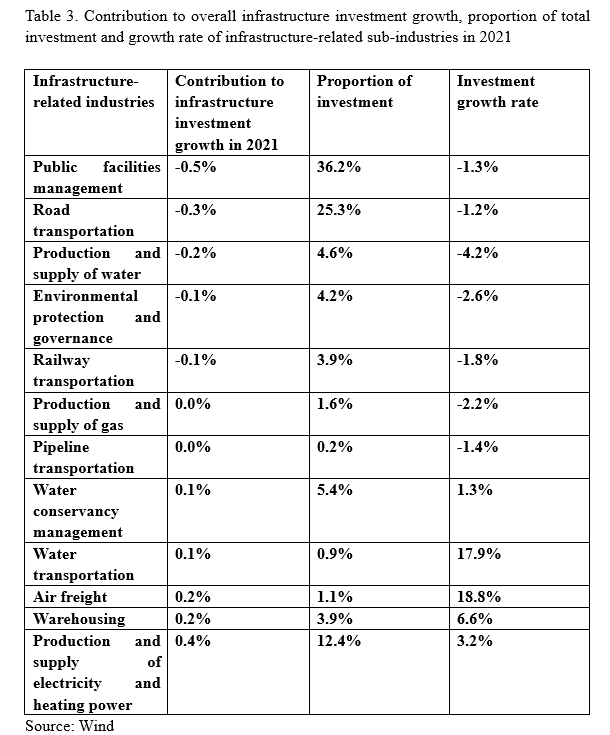

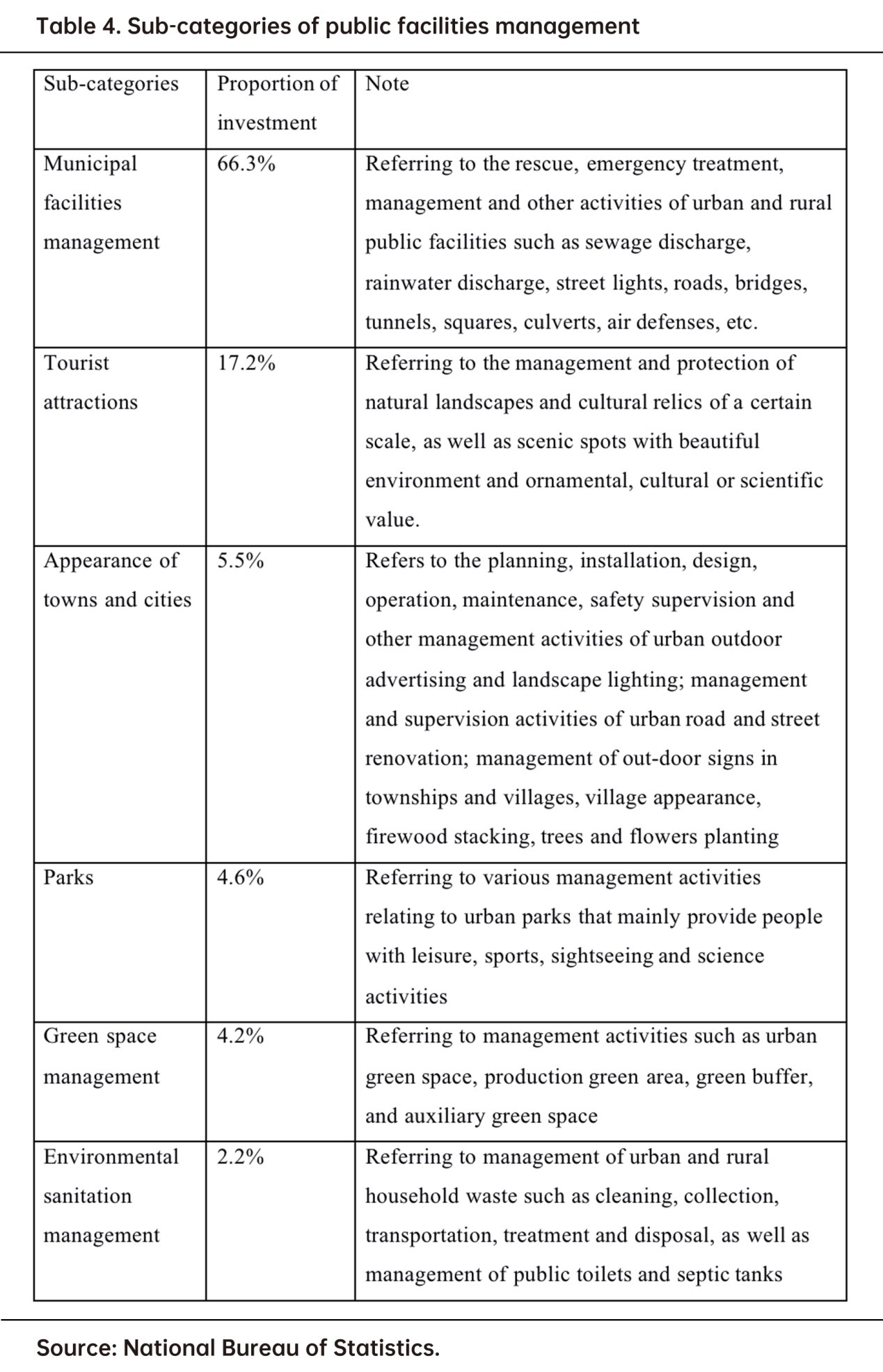

The biggest blow to the growth of infrastructure investment comes from investment in water conservancy, environment protection and public facilities management. The largest investment in public facilities management is municipal facilities management which accounts for 66.3% of total. Therefore, the sluggish growth of infrastructure investment may be mainly a result of the slowdown in urban municipal construction and road investment.

V. THE SIZE OF VARIOUS SOURCES OF FUNDS NEEDED FOR INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT TO GROW AT 6%

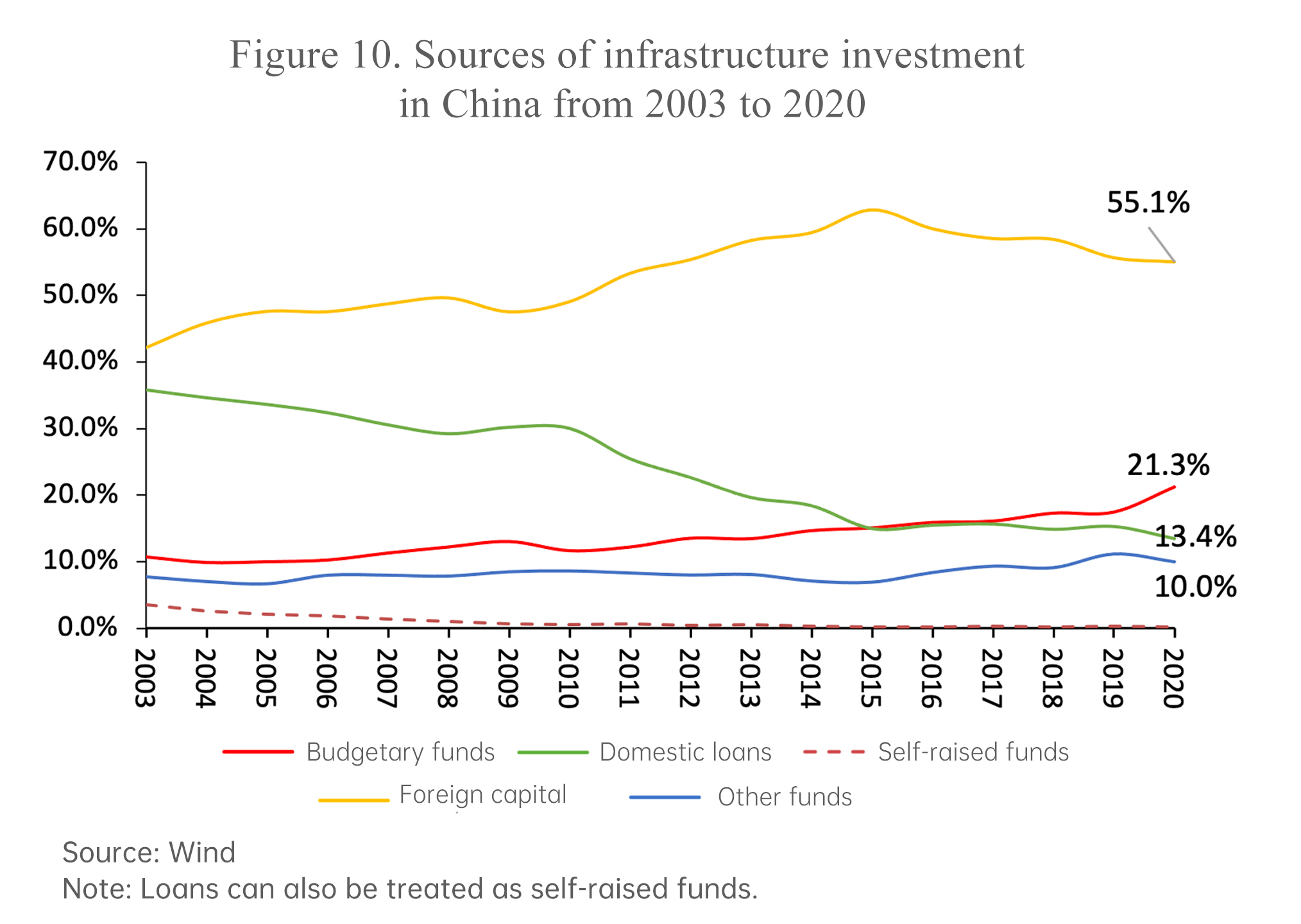

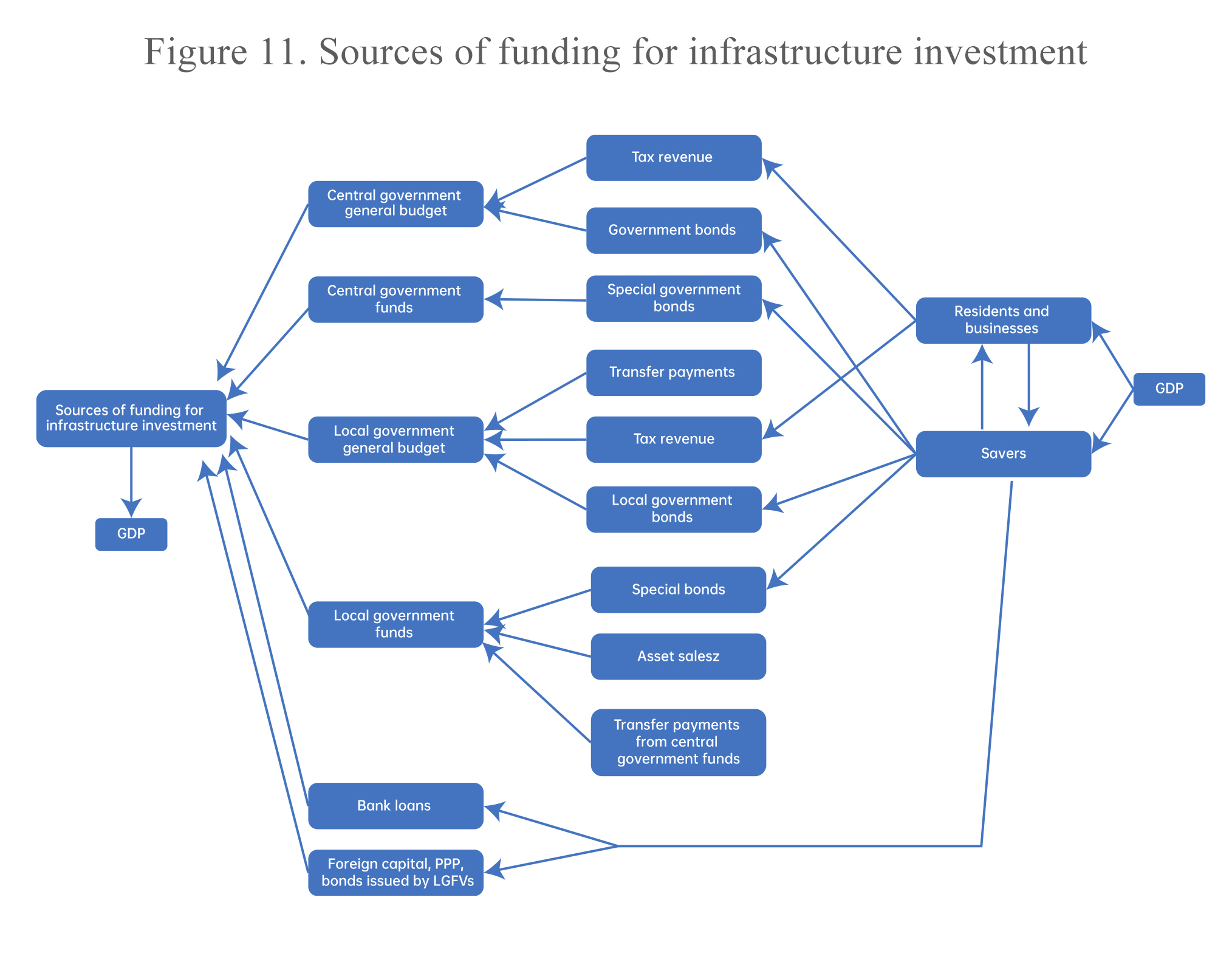

Infrastructure investment mainly comes from budgetary funds, domestic loans, self-raised funds, foreign capital and other funds.

From a practical point of view, self-raised funds include four major parts: 1) the company's own funds; 2) nonstandard financing of the company; 3) funds from non-governmental entities in PPP infrastructure projects; 4) bonds raised by local government financing vehicles (LGFVs).

Figure 11 depicts the flow of infrastructure funds among various entities. It can be seen that residents and enterprises, especially residents as taxpayers, savers and ultimate investors, are the ultimate investors of infrastructure investments. The ability of residents and businesses to provide capital depends not only on their income, but also on their propensity to save.

1. Budgetary funds

The budgetary funds mainly come from three sources, i.e. general public budget, special bonds, and land transfer revenue.

1) Funds from general public budget

According to calculations based on the latest data, the actual amount of the general public budgetary expenditure on infrastructure investment in 2021 is 2 trillion yuan.

The infrastructure investment in the general public budget of the central government in 2020 is 71.6 billion yuan, accounting for 3.3% of the infrastructure funds from the general public budget. Assuming that the proportion of investment in infrastructure programs in the central-local government general public budget remains unchanged, the funds used for infrastructure investment in the central and local government general public budgets in 2022 should be 76 billion yuan and 2.19 trillion yuan respectively, totaling 2.27 trillion yuan.

2) Funds from land transfer revenue

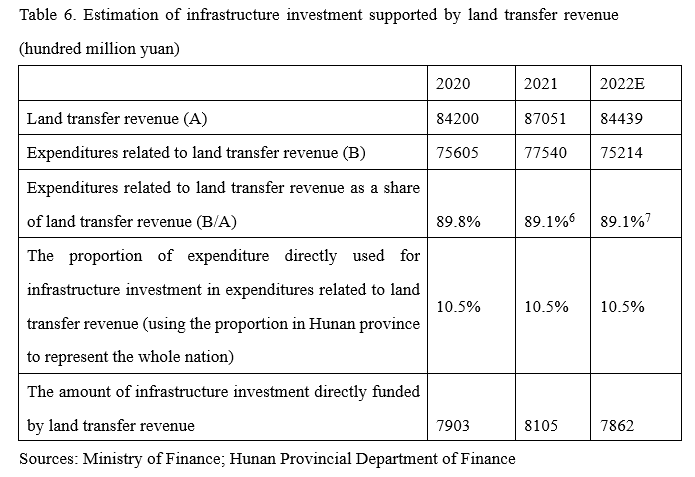

Historical data show that most of the land transfer revenue was used as compensation for land acquisition and land levelling, while a small part may be transferred into general public budgets and only 10% was directly used for infrastructure investment.

As the statistics for expenditure related to land transfer revenue at the national level are not available, relevant figures are estimated based on the spending structure of Hunan province in 2020. According to the 2020 final accounts of Hunan province, among the expenditures related to land transfer revenue, infrastructure-related expenditures including “expenditure on urban development” and “expenditure on rural infrastructure building” reached 25.6 billion yuan combined, accounting for 10.5% of the total.

Let’s assume that the national expenditures related to land transfer revenue as a share of land transfer revenue in 2022 is 89.1%, the same as that in 2021. Given the downward pressure on the real estate market and the cooling of the land market, the growth rate of national land transfer revenue in 2022 could be set as -3%. In this case, the national land transfer revenue in 2022 should be 8.44 trillion yuan, and the related expenditures should be 7.52 trillion yuan. If we assume that the proportion of expenditure for infrastructure investment in total expenditures funded by land transfer revenue in 2022 remains the same as that in 2021 at 10.5%, the amount of infrastructure investment funded by land transfer revenue would be 786.2 billion yuan.

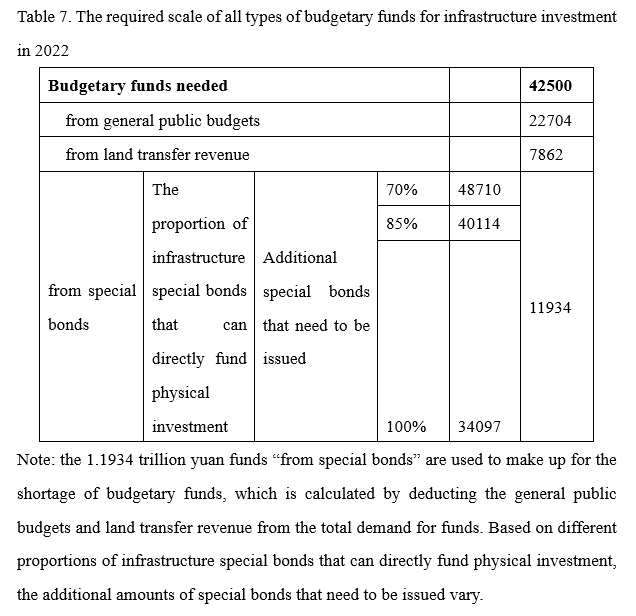

3) Funds from special bonds

As has been estimated, in order to achieve an economic growth rate of 5.5%, the scale of infrastructure investment in 2022 should reach 20 trillion yuan. If we assume that the share of budgetary funds for infrastructure in 2022 is the same as that in 2020 at 21.3%, the funds should amount to 4.25 trillion yuan. As has been estimated that infrastructure investment funded by the central and local general public budgets and land transfer revenue in 2022 will be 2.2704 trillion and 786.2 billion yuan respectively, to make up for the shortage of budgetary funds for infrastructure investment, special bonds for infrastructure investment in 2022 should be 1.1934 trillion yuan.

If we assume that the proportion of special bonds used for infrastructure is 35%, and set different percentages of the amount of actual investment directly coming from the issuance of special bonds, the results are as follows (Table 7):

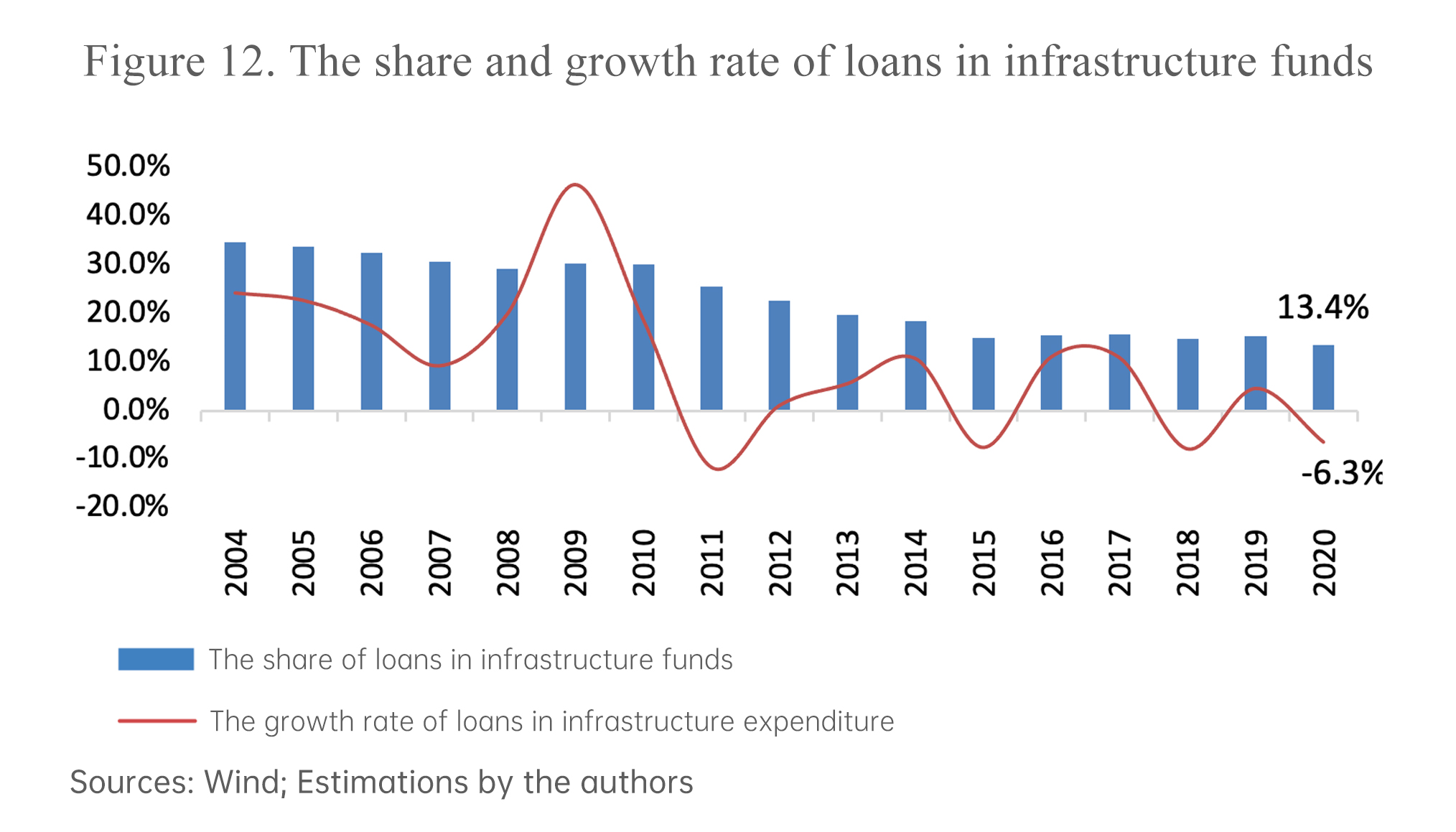

2. Bank loans

Given that the share of banks loans in infrastructure funds between 2015 and 2019 remained at around 15%, the average share (15.2%) could be used to represent the figure in 2022. In this case, to realize a total scale of infrastructure funds at 20 trillion yuan, banks should provide loans of at least 3 trillion yuan for infrastructure investment in 2022.

3. Self-raised funds

3. Self-raised funds

Over a decade, self-raised capital has been accounting for an increasing share of infrastructure funds from 42.1% in 2003 to 55.1% in 2020, making it the major source of infrastructure investment.

On the assumption that the proportions of infrastructure funds from foreign capital and other sources in 2022 remain the same as in 2020, which stand at 0.2% and 10% respectively, if the overall amount of infrastructure investment is 20 trillion yuan, then the amount of foreign capital and other funds should be 39.5 billion and 2 trillion yuan respectively. As has been assumed that infrastructure investment funded by government budget and bank loans are 4.25 trillion and 3 trillion yuan respectively, the self-raised funds for infrastructure in 2022 should reach 10.7 trillion yuan.

Self-raised funds include four major parts: 1) the company's own funds; 2) nonstandard financing of the company; 3) funds from non-governmental entities in PPP infrastructure projects; 4) bonds raised LGFVs. We assume that of the infrastructure investment in 2022, enterprises’ self-raised funds can represent a share of 15%, which is equivalent to 1.6 trillion yuan. Among the other three sources, nonstandard financing is negligible, while funds from PPP projects might amount to 0.9 trillion yuan, so the remaining 8.2 trillion funds may need to be covered by LGFVs.

Assuming that all the urban investment bonds would be used for infrastructure investment, to make up for the gap of funds needed, the new issuance of urban investment bonds in 2022 should reach 8.2 trillion yuan, with a growth rate of 31.6%.

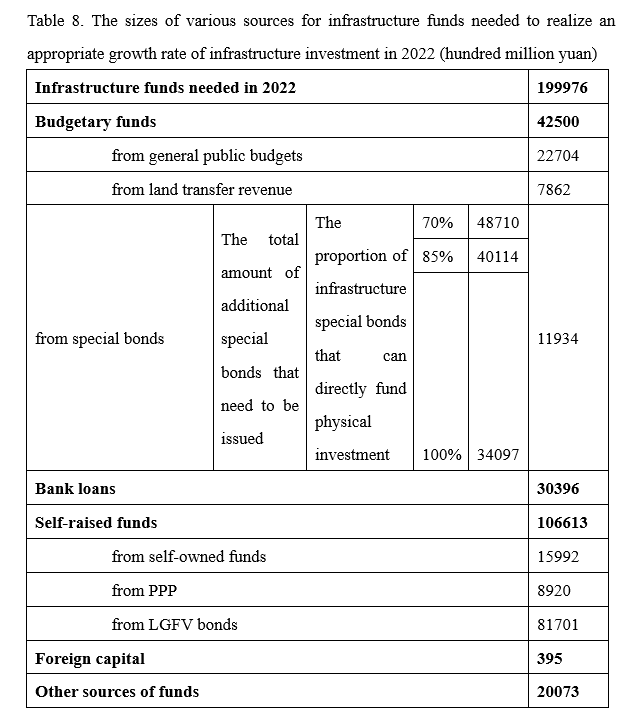

Combining all the calculations above, to realize an appropriate growth rate of infrastructure investment, the specific sizes of various sources of infrastructure funds can be reckoned (Table 8) on the premise that the basic structure of these fund sources remain the same.

VI. HOW SHOULD MACROECNOMIC POLICIES HELP ACHIEVE A 6% GROWTH RATE OF INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT

The core of expansionary fiscal policy is increasing government spending, which often (but not always) means a rise in fiscal deficit. Any expansionary fiscal policy will have some negative impacts on the future development of an economy, mainly in the form of rising government debt, intensified financial vulnerability, and worsening inflation. As a result, after the crisis, the government needs to withdraw the countercyclical policy adopted previously in order to overcome the legacy created by such policy and let the economy grow on its own. In practice, the exit process might be accomplished within a short timeframe but can also drag on for a long time. In some cases, a poorly executed policy withdrawal might have more serious long-term implications than the recession itself on the economy. Therefore, when designing fiscal policies to offset certain internal or external factors that slow down economic growth, we should control the intensity of expansion and leverage appropriate means and approaches to avoid or reduce mistakes and mitigate the fallout.

Based on the analysis of this paper, in order to realize a GDP growth of 5.5%, infrastructure investment should grow at 6% and amount to 19 trillion yuan, under the condition that other macroeconomic aggregates change at the rate we set. Correspondingly, the overall nominal amount of infrastructure investment should be 20 trillion yuan, of which 21% comes from budgetary funds (general public budgets, land sales, and special bonds), 15% from bank loans, 53% from self-raised funds, and 5% from foreign capital and other sources.

Whether infrastructure investment can grow at 6% in 2022 relies on: first, sufficient project reserves; second, the initiative of local governments; lastly, the adequacy of funds.

Investment potential and project reserves for infrastructure

The sluggish growth of infrastructure investment in 2021 is mainly attributed to the declining investment in “public facilities management”, especially in “municipal facilities management”. The reality is that Chinese cities at all levels, including metropolises like Beijing and Shanghai, still face a severe shortage of investment in municipal facilities management rather than investment saturation.

On top of that, the 14th five-year plan proposes to promote the development of major projects like “new infrastructure, new urbanization, transportation and water conservancy. To serve key national strategies, major projects will be implemented such as the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, the new western land-sea corridor, national water network, hydropower project in the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River, interplanetary exploration, and industrialization of BeiDou Navigation Satellite System; the construction of major projects that can strengthen the foundation, improve functionality, and yield long-term benefits will be accelerated such as major research facilities, protection and restoration of major ecosystems, public health emergency response, major water diversion, flood control and disaster mitigation, power and gas transmission, and transportation along borders, rivers, and coasts . It is evident that China’s demand for infrastructure investment is enormous, both in the field of traditional municipal facilities and transportation as well as new infrastructure.

Indeed, demand for infrastructure investment does not necessarily mean such investment could be materialized. The key lies in project reserves. The experience of “4 trillion” stimulus package in 2009 shows that any project launched in a rush will lead to waste of resources and lower efficiency, which will have repercussions on economic development in the future. The National Development and Reform Commission is absolutely right in proposing “appropriately front-loading infrastructure investment”. But the precondition for such “front-loading investment” is the adequacy of project reserves. The rollout of infrastructure investment projects in 2022 should not repeat the mistake of hastiness in 2009.

The initiative of local governments

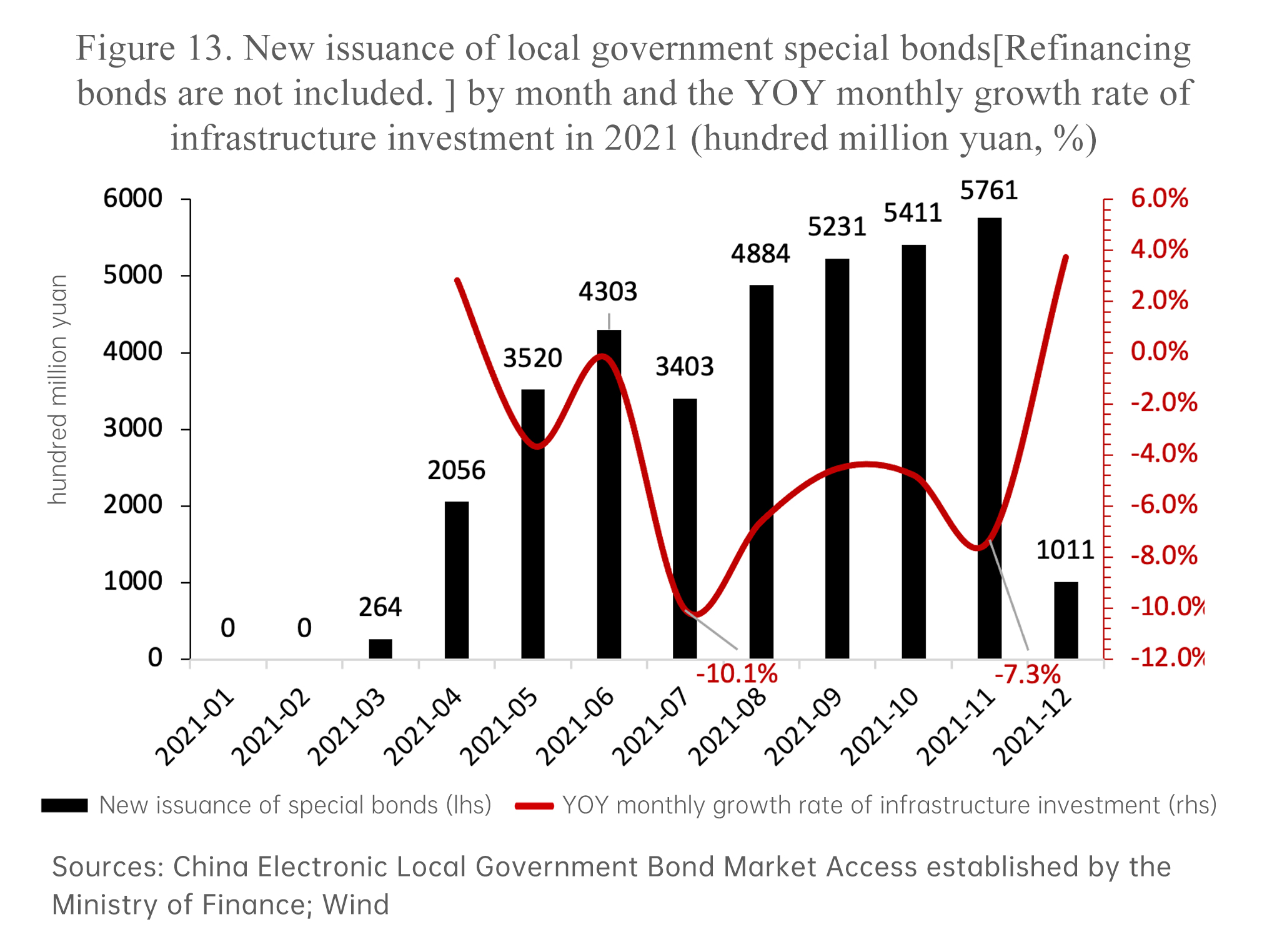

The main area of infrastructure investment is the construction of municipal facilities. Although enterprises are the main implementer of infrastructure construction, local governments play an important role in planning, coordinating, and supervising infrastructure investment at the local level. In 2020, local governments issued 3.75 trillion yuan of special bonds. However, the revenue into local government-managed funds exceeded the expenditure through such funds, creating a surplus of 1.98 trillion yuan . In 2021, no new local government special bonds were issued during the first two months; in March, new issuance amounted to 26.4 billion yuan; afterward, new issuance stepped up from April to June (Figure 15). But the year-on-year growth rate of infrastructure investment started to turn negative in June and plummeted to -10.1% in July. The issuance and use of special bonds demonstrate that the growth of China’s infrastructure investment was slow in 2021. One important factor for this sluggishness is the lack of initiative of local governments.

Through further exploration, it can be found that the lack of initiative of local governments in infrastructure investment seems to be attributed to two reasons: first, the debt repayment pressure on local governments is so great that they must first try to lower the leverage ratio. As a result, more and more funds are used for debt service instead of infrastructure investment; second, “l(fā)ifetime accountability” makes them reluctant to risk investment failure.

As the saying goes, “you cannot have your cake and eat it too”. To implement expansionary fiscal policy, the central government must strike a proper balance between lowering the government’s leverage ratio (especially that of the local governments) and ensuring steady economic growth. Overall, deleveraging should not be achieved at the cost of slowing down economic growth; local governments should play their role in planning, coordinating, and supervising infrastructure investment.

Structure of infrastructure investment financing

Infrastructure, by its very nature, is a public good and is generally very difficult to have returns in the short term, which is the only reason why private investors are generally not willing to finance infrastructure investment. Only governments that aim at public welfare rather than profitability will finance such investment.

For infrastructure financing, whether it is raising funds from bank loans or issuing bonds in the capital markets, the fund providers and the ultimate investors are all aiming to make a profit. Even state-owned commercial banks have to achieve their profit objectives.

We divide the sources of funding for infrastructure investment into two main parts: budgetary funds and self-raised funds. The former mainly includes general public budget funds, special bonds and land transfer expenditures; the latter includes urban investment bonds, bank loans and others. The financing structure of infrastructure investment in China has the following characteristics:

Firstly, in China, budgetary funds contribute to a very small share of infrastructure investment, typically only around 20%. Self-raised funds, on the other hand, account for as high as about 80%.

Of the budgetary funds, the proportion of the general public budget expenditure that directly forms infrastructure investment continues to decline, and in 2020 this proportion is only 8.7% (Table 6). The contribution of the central government's general public budget to infrastructure investment is even smaller, at only a few tens of billions of yuan, which is negligible.

Second, among the budgetary funds, special bonds issued by local governments are the most important source of infrastructure investment.

To prevent local governments from over-borrowing, the government has set a high threshold for the issuance of special bonds, requiring that "construction projects financed by special bonds should be able to generate a continuous and stable cash flow in the form of government fund income or income from special projects, and the cash flow should be able to fully cover the debt service expense of the special bonds". In reality, only a few infrastructure projects can meet such requirements. Special bonds require yields which should be able to cover at least 1.1 times the principal and interest payment on the bonds. This feature conflicts with the nature of infrastructure investment as public goods. However, special bonds are public debt and the credit risk is low, even though the yield is low. Long-term investors such as commercial bank proprietary accounts and insurance companies are willing to own special bonds.

Under the current system for special bond management, strict conditions have to be met at every step of the process, from obtaining a quota, applying for project approval, issuing the bond, to allocating the funds. The procedures are cumbersome. Maybe that’s why only 60.8% of the special bonds issued in 2020 went into physical investment in the year.

Expenditure out of land transfer revenue is unsustainable and its role in infrastructure investment will become increasingly limited. We will not further discuss it here.

Third, while stimulating economic growth through greater investment in infrastructure, the central government wants to increase neither the general public budget deficit nor the local government debt too much and has imposed restrictions on local government borrowing. Meanwhile, local governments are disinclined to increase their debt. Thus, to meet the need to build infrastructure on the one hand, but unwilling (or not allowed) to go into debt on the other, local governments set up "local government financing vehicles" (LGFVs) which issue bonds or borrow from banks as business entities. In fact, the amount of "self-raised" funds is much larger than the amount of "budgetary" funds.

The most significant part of self-raised funds is bonds issued by LGFVs. Unlike special bonds, the issuers are not the local government. The two are connected but have different legal statuses. In contrast to special bonds, the payment of principal and interest on these bonds depends entirely on the cash flow generated by the investment projects. Despite the government background of the LGFVs, the credit of LGFV bonds is completely separated from government credit. Compared to general public expenditure and special bonds, the most important feature of "self-raised" funds is that there is no longer an explicit or implicit government guarantee; therefore, the financing cost of urban investment bonds is higher than that of special bonds. However, for investors with a higher level of risk tolerance, such as banks, trusts, securities firms and investment funds, these bonds are still a good choice.

To curb the growth of hidden debts of local governments, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) has gradually developed a "list system" for the management of LGFVs since 2010. The different categories of LGFVs on the list are subject to different degrees of restrictions on bond issuance. The reduction in the volume of urban investment bond financing should have been related to the strengthening of regulation.

Among the self-raised funds, bank loans related to infrastructure development are mainly invested in LGFVs (urban investment companies). Infrastructure loans are long-term loans and the term of bank loans normally do not exceed three years. However, because of the size of China's banks and the abundance of capital, loans can be rolled over. Also, although banks won’t lend for purely public interest projects, these projects can be packaged with non-public interest ones. Thus, lending to urban investment companies is consistent with banks' strategic objective of achieving long-term stable returns. As a result, banks are highly motivated to lend to LGFVs.

However, to curb the increase in hidden debt of local governments, regulators have imposed strict restrictions on banks' lending to LGFVs. For example, banks can only lend to enterprises on the "list" of LGFVs only if they meet certain conditions. Banks may lend to LGFVs that have been approved by the CBIRC to withdraw from the "list", but the conditions for lending are more stringent. The strict supervision of the financing activities of urban investment companies is likely the main reason for the continuous decrease in the amount of bank loan for infrastructure in recent years, as well as the decrease in the share of total financing.

In theory, infrastructure investment can be financed entirely from the government's general public budget, and if a budget deficit arises as a result, the government can issue bonds to cover it. In this case, financing costs could be minimized. However, this approach could not only cause government debt to get out of control but also create problems such as inefficiency and moral hazard. Conversely, if the government is already in a difficult fiscal situation and unable to finance infrastructure investment, or has concerns of inefficiency and moral hazard, it will try to minimize “budgetary” financing and turn to various forms of “self-raised” funds, inevitably leading to higher financing costs. To curb the financial risks (shadow banking, defaults, etc.) associated with the conflict between the requirement for return by “self-raised” funds and the public interest nature of infrastructure projects, regulators must strictly regulate all forms of “self-financing”. For example, raising the threshold for bond issuance, restricting and prohibiting banks from lending to certain companies engaged in infrastructure investment. Tighter regulation will inevitably lead to reduction in the availability of financing and increase in the cost of capital. Infrastructure investment has declined due to insufficient low-cost finance. As a result, it could only provide less cushion to shocks to the economy, leading to slowdown of growth which in turn causes the government's fiscal position to worsen. A vicious cycle forms of declining economic growth, deteriorating fiscal position and increasing financial risks.

Restructuring infrastructure investment financing

Clearly, China's current structure of infrastructure investment financing reflects the government's intention to find the optimal balance between maintaining economic growth and avoiding deterioration in the government's fiscal position as well as an increase in financial risk. But the optimal balance can also be adjusted. In China's current situation, "stabilizing growth" has become a priority of the macroeconomic policy. To achieve a GDP growth rate of 5.5%, China's infrastructure investment should grow by 6%, and infrastructure financing should reach 20 trillion yuan.

China should be able to raise sufficient funds for infrastructure investment, provided that the previous financing structure is largely maintained. However, due to the low share of the public budget in infrastructure investment, market investments seeking low risk and high returns may be reluctant to provide more funds for infrastructure projects or would demand higher risk premium against the backdrop of a continued decline in economic growth. Meanwhile, strict regulation has made it more difficult for infrastructure projects to obtain the necessary funding and for fund suppliers to provide the required capital.

To ensure adequate low-cost financing for infrastructure investment, it is necessary to restructure China's infrastructure financing.

First, increase the proportion of the general public budgetary funds in infrastructure financing. Infrastructure investment generates non or little revenue in the short term (or even in the long term). Therefore, public finance should use funds from the general public budget, either through taxation or the issuance of government bonds, to finance infrastructure investment. Some countries have been unable to raise funds because of fiscal difficulties, or have raised funds for infrastructure investment by means other than increasing public expenditure for reasons of efficiency and avoiding moral hazard. China does not have such a problem. We should increase the support for infrastructure investment by the general public budget, and make budgetary funds the mainstay of infrastructure financing.

Second, the deficit rate should be raised and the scale of government bonds should be expanded. Without changing the financing structure, and to achieve a suitable rate of infrastructure growth, general budgetary expenditure should reach a growth rate of 7.7% in 2022. Assuming that the growth rate of general public budget revenue in 2022 is in line with 2019 at 3.8% (which is already an optimistic estimate given the downward trend of fiscal revenue), the actual general budget deficit will be 5.5 trillion yuan, up by 1.12 trillion yuan compared with 2021. With the change in the financing structure, the actual deficit will widen further, which should allow for a further increase in the deficit ratio in 2022, the extent of which will depend on the achievement of the growth target. If the fiscal deficit increases as a result of infrastructure investment, the government is well placed to cover the deficit by issuing bonds. China's government bond market is still underdeveloped. The issuance of additional government bonds is conducive to both increased infrastructure investment and the deepening of China's government bond market, so why not?

Third, to support local governments in infrastructure investment, transfer payments from the central government to local governments could be increased to replace the issuance of special local government bonds and urban investment bonds which lack market demand.

Another option is to support public interest infrastructure through the issuance of discount bonds subsidized by fiscal funds or policy-based financial institution bonds. Such non-budgetary, low-interest-rate bonds are a workaround for the central government to support local infrastructure investment.

Fourth, improve the efficiency of special bonds.

Under the current special bond management system, special bonds are difficult to form disposable financial resources for local government and are used inefficiently. In 2022, if the proportion of physical investment formed by special bonds is 100%, 85% and 70% respectively, then an extra supply of special bonds of 3.4 trillion, 4 trillion and 4.9 trillion will be required. Therefore, the role of special bonds in supporting infrastructure largely depends on the efficiency of them being transformed into physical investment.

Fifth, commercial banks should be given greater discretion to decide on the purchase of various types of infrastructure-related bonds and the grant of loans to urban investment companies based on considerations of returns and risks. Of course, commercial banks need to go through a rigorous approval process to obtain the appropriate qualifications.

Sixth, open up new channels for infrastructure financing through financial innovation. Chinese financial institutions are beginning to experiment with innovative tools and channels for financing infrastructure projects, in order to expand the scale of financing and reduce costs and risks. For example, in some provinces, real estate investment trusts (REITs) are being used to raise funds for infrastructure projects. Many attempts have been made in this regard in developed countries, and it is worthwhile for us to learn from them.

Seventh, to ensure smooth financing of infrastructure investment, the monetary authorities must work with the fiscal authorities, implement an expansionary policy and keep interest rates down, so as to reduce the various costs associated with infrastructure financing.

VII. CONCLUSION

To implement the central government’s strategic objective of "stabilizing growth", China should strive to achieve a GDP growth rate of 5.5% in 2022. To achieve this target, infrastructure investment should grow at 6% and total investment should reach $20 trillion.

China’s current infrastructure financing system and financing structure are not fully adapted to the need to stimulate economic growth through increased fiscal spending. As can be seen from the sources of funding for infrastructure, self-raised funds such as urban investment bonds take up the largest proportion, followed by bank loans, special bonds, and general budgetary expenditures, and the costs of these funds also descend in that order. In other words, the more expensive the funds are, the more they are used.

To achieve the growth target for infrastructure investment, the government must adjust the existing financing structure and significantly increase the portion of the general budgetary funds in total financing. Regulations could be moderately relaxed to give enterprises and financial institutions more discretion in raising finance. Innovations by financial institutions to address the difficulties in financing infrastructure investment should be encouraged.

To achieve the growth target, the Chinese government must find a dynamic balance between economic growth and financial stability. In 2022, the balance should be tilted more towards growth. The ability to achieve higher rates of infrastructure investment is key to "stabilizing growth" in 2022.