Abstract: Common prosperity embodies the essence of socialism, and is an important feature of China's modernization drive. Finance needs to play its due role in realizing common prosperity. Sound financial development reduces inequality, while financial repression and excessive financialization exacerbate it. China is characterized by the coexistence of financial repression and financial catch-up, both of which have played a part in driving a widening income gap. This article proposes five policy suggestions to give full play to finance in promoting common prosperity: (1) finance should serve the real economy; (2) promote orderly development of the real estate sector; (3) protect farmers' land property rights and narrow the urban-rural income gap; (4) boost inclusive finance; (5) make sure that Fintech does good.

Since the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, criticism of finance has prevailed worldwide. The "Occupy Wall Street" movement saw a swelling financial sector the culprit for the widening wealth gap. Thomas Piketty presented a vast body of empirical data to prove that "capital is back" in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The emerging Fintech sector, while promoting socio-economic development and creating new models of wealth growth, has also played a role in polarization. There are also increasing discussions in China of excessive financialization, disorder in the financial markets, reckless expansion of capital, etc.

Finance has positive roles, too. Many scholars have highlighted the importance of financial revolution to the Industrial Revolution, how a laggard financial sector put China on the wrong side of the Great Divergence and how its prosperity helped China to catch up. They seem to be talking about "finance" in a different world.

On finance, different stories are told. But a series of dark financial narratives have directed more attention to distributional inequality (rather than economic growth as before) since this wave of GFC broke out, with special implications:

If we want finance to do good in serving the real economy, reducing instead of increasing inequality, and promoting inclusive development and common prosperity, we need to bring out its special qualities, clearly define its roles, step up financial reforms, and reshape its development model.

I. FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMON PROSPERITY: THE CHINESE STORY

Since the reform and opening-up was launched, Chinese people have rapidly built up their individual wealth; at the same time, the wealth gap has significantly widened. This, in addition to the coexistence of financial repression and financial catch-up, has vividly told a unique Chinese story of financial development and common prosperity.

1. "Unprecedented" growth of income and wealth

Finance has contributed to two miracles China created over the 4 decades of reform and opening-up: rapid economic development, and long-term social stability. While promoting growth by converting savings into investment, China’s financial system has managed to maintain long-term stability and stay immune to financial crises. As a result, China has witnessed unprecedented growth of national income and wealth.

(1) National income

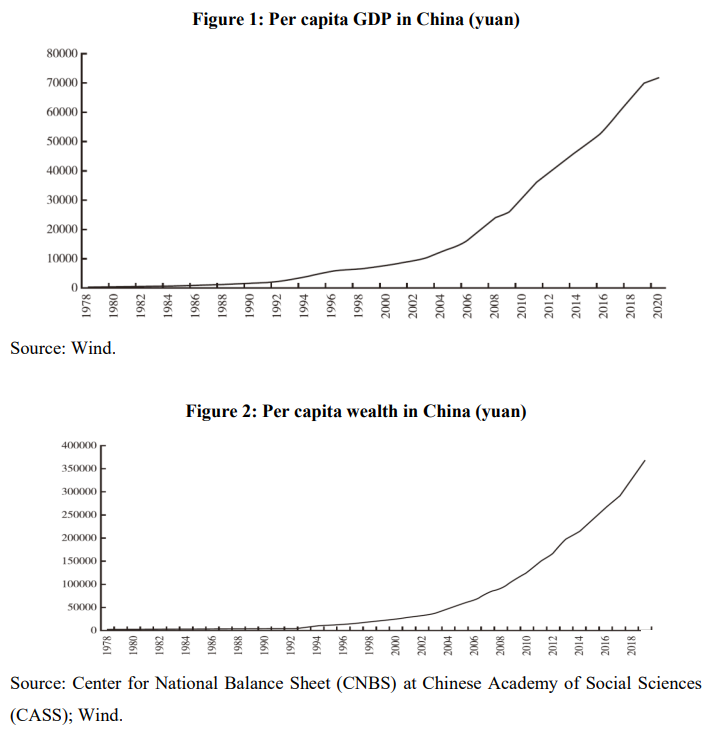

China’s gross domestic product (GDP) surged from 367.9 billion yuan in 1978 to 83.2 trillion yuan in 2017, with an average annual real growth of 9.5%, much higher than the world average of 2.9% in the same period. In 2020, it recorded a GDP of over 100 trillion yuan for the first time in history. At the same time, China’s per capita GDP ballooned from 385 yuan in 1978 to 72,000 yuan in 2020, higher than 10,000 USD and nearing the threshold for a high-income economy (Figure 1).

(2) National wealth

According to latest estimates by the Center for National Balance Sheet (CNBS) at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), as of 2019, China recorded a total net wealth of 675.5 trillion yuan and a per capita net wealth of 482,000 yuan, of which the household sector held a total of 512.6 trillion yuan, with the per capita number at 366,000 yuan.

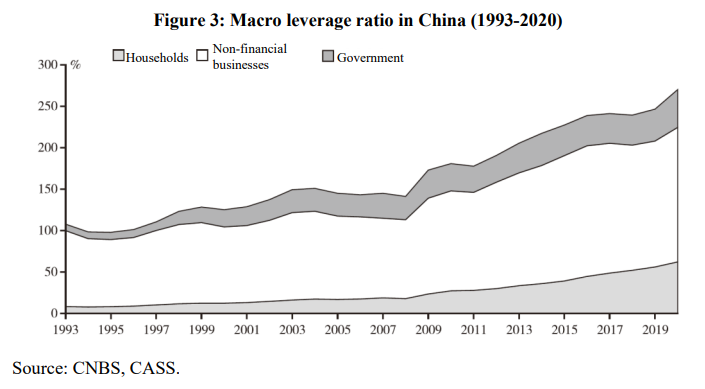

Since reform and opening-up, growth of per capita wealth accumulated by Chinese households has been impressive. As seen in Figure 2, back in 1978, Chinese households had per capita wealth lower than 400 yuan. It rose to over 4,000 yuan in 1992 after Deng Xiaoping's famous visit to Southern China, exceeded 10,000 yuan in 1995 and 100,000 yuan in 2009, and reached 366,000 yuan in 2019.

During 1978-1989, China recorded a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19.8% in its per capita household wealth, which stood at 25.7%, 18.9% and 13.3% respectively during 1990-1999, 2000-2009, and 2010-2019. Clearly, per capita household wealth in China grew the fastest in the 1990s.

As the Chinese economy entered the new normal in 2010, growth of its per capita household wealth has also slowed. But in general, the stunning accumulation of household wealth in China since the reform and opening-up was unprecedented in history.

2. Widening income and wealth gap

With rapidly expanding national income and wealth, China gradually shrugged off poverty and backwardness. In 2020, China successfully delivered its first centennial goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects, demonstrating the results from its dedication to inclusive growth and common prosperity.

Since the 18th CPC National Congress in 2012, common prosperity was given increasing prominence, with stronger measures rolled out to improve people's livelihood and alleviate poverty in order to realize the goal of building a moderately prosperous society, laying a solid groundwork for efforts toward common prosperity.

However, China still has a large wealth gap and a long way to go in improving income distribution and promoting common prosperity.

(1) Income distribution

According to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China’s Gini coefficient for income distribution has been rising ever since the advent of the 21st century, peaking in 2008 at 0.491. It went downward during 2008-2015, indicating a narrowing of the income gap, but climbed back up to 0.465 in 2019, still higher than the global “red line” of 0.4.

(2) Wealth distribution

For many economies around the world, the Gini coefficient for wealth distribution seems to be higher than that for income distribution.

Credit Suisse's Global Wealth Report shows that the Gini coefficient for wealth distribution in China went on a continuous rise during 2000-2015 from 0.599 to 0.711, after which it slid to 0.697 in 2019 but went back up to 0.704 in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to estimates by Luo Chuliang and Chen Guoqiang (2021), based on household survey statistics from the Chinese Household Income Project Survey (CHIP) in 2013, China Education Panel Survey (CEPS) in 2012 and China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in 2016, the Gini coefficient for household wealth in China was as high as 0.619 and 0.736. The coefficient went further up to around 0.8 after the authors filled in some of the missing data on high-income individuals with data sourced from China's "Rich Lists".

Wan et al. (2021) found that, based on data from 4 rounds of China Household Finance Survey (CHFS), the increasing divergence in real estate holding was the biggest factor behind the widening wealth gap among Chinese households, explaining 70% of wealth inequality, and this percentage is still on the rise as time goes by. Nationwide, real estate explained 71.86% of household wealth inequality in 2011, and the percentage rose to 75.49% in 2017; in urban areas, it rose from 74% in 2011 to 76.57% in 2017, while in rural areas, from 58.48% to 64.09%.

In addition, according to data from world inequality database on the top 10% richest people in five major economies including China, in 2000, the wealth in the hands of the richest 10% in China accounted for less than 50% of the total wealth of all groups, lower than the United States, France, the UK, Russia and other economies. But after that, the wealth gap in China increased rapidly, becoming wider than that in the United Kingdom, France and other European countries with greater focus on social justice and welfare and approaching the levels in Russia and the United States. Proportion of the wealth of the top 10% richest people in China in total household wealth increased from lower than 0.478 in 2000 to 0.667 in 2011, after which it gradually stabilized.

3. Finance and inequality: dual impacts from financial repression and China's financial catch-up

Financial development in China needs to be understood in the context of its general economic development, the core of which is to catch up with developed economies. To that end the Chinese economy needs to transform and to advance. In order to enable both goals, China has introduced a series of financial mechanisms and policies with its own characteristics, and brought about the coexistence of financial repression and catch-up.

"Financial repression" means that the government intervenes in various forms in the interest rate, the exchange rate, capital allocation, the establishment and operation of large financial institutions and cross-border capital flows, etc.

From a neoclassical economics view, financial repression is detrimental to economic growth and financial stability because it is a kind of distortion that disrupts resource allocation and risk pricing, reduces the efficiency of financial resource allocation and depresses financial development.

However, put in the context of China’s economic catch-up, financial repression has special implications. Research shows that in the early stage of development, with an immature financial market and large demand for industrial capital, proper financial repression has played an important role mobilizing resources and driving growth, making it a type of "benign distortion" (Zhang Xiaojing, et al., 2018).

But as China enters the rank of high-income economies, it needs to phase out repressive financial policies and address financial distortions as part of its supply-side structural reform of the financial sector.

"Financial catch-up" is mainly featured by the fast expansion of the financial sector and the rise of Fintech as a key force enabling China to “l(fā)eapfrog” its global competitors. By "catch-up", we mean that related financial indicators have exceeded the level corresponding to China's stage of economic development (such as measured by per capita income).

Generally speaking, financial repression curbs financial catch-up. But in China, financial repression has served as the catalyst instead. The key logic here is that financial repression alone would result in simplified, government-led financial development with formal and informal systems running parallel to each other; but Fintech-driven financial innovation could bring changes to such "binary" landscape by empowering informal systems such as shadow banking while stimulating new types of financial ecology (such as when big techs engage in financial services).

Financial catch-up can be deemed as a breakthrough of financial repression and various financial regulations. It is driven by two forces: Fintech development, and regulatory tolerance. These are two new lenses through which we can observe China's financial development.

(1) Financial repression and its distributional effects

In a development-oriented view, financial repression's goal is to enable China's economic catch-up, and so greater emphasis has been placed on growth, with the consequent distributional effect overlooked.

Financial repression in developing economies could distort the price of funds, leading to credit rationing. As a result, individuals and businesses would have unequal access to credit, the financing channel would be impeded, and income gap would widen, giving rise to a vicious cycle: underdeveloped economy – underdeveloped financial sector – fund shortage – financial repression – credit rationing – unequal access to credit – widening income gap.

Financial repression prevails in China, mainly demonstrated by interest rate and exchange rate control, credit rationing and restrictions on the establishment of financial institutions. The government, by way of financial repression, directly allocates rent among various economic departments, which inevitably affects income distribution. With the real lending interest rate lower than the equilibrium rate, and credit demand far bigger than supply, credit rationing or selective credit policies have given advantaged players (state-owned economy, heavy chemical industries, cities, big companies) greater access to higher-quality financial services, leaving disadvantaged groups (private sector, small- and medium-sized businesses, rural or remote areas) underserved. Credit-related discrimination, be it ownership-, industry- or area-based, will result in imbalance and discoordination, exacerbating inequality.

Moreover, repressive financial policies erode households' asset income. When financial repression is in place, the official interest rate stays far below the market rate over a long period of time; it is also manifested by dominating state-owned banks and high market thresholds. Putting a cap on deposit interest rate, while reducing the investment cost of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to a certain extent, has also pushed the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio of the Chinese banking sector back to a normal level; however, the distorted capital price has misled investment while dealing negative blows to household income, slashing households’ proceeds from savings. Repressive financial policies have bred a wealth distribution mechanism where households’ income is sacrificed to subsidize businesses and local governments, including local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), thus eroding households' asset income.

(2) Financial catch-up and its distributional effect

China's financial catch-up is seen in the rising macro leverage ratio, higher value added of the financial sector, and the country's emergence as a global Fintech pioneer, among others. All of these have distributional effect to various extents.

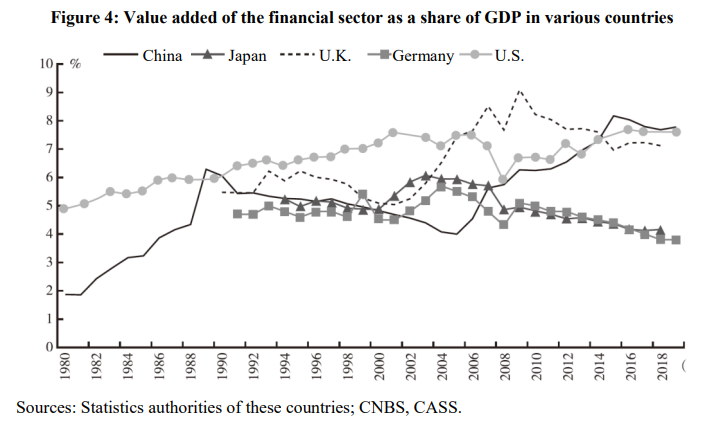

First, surge in the macro leverage ratio.

China's macro leverage ratio climbed up slowly before the 2008 GFC. It fell slightly amid a spontaneous deleveraging drive during 2003-08, but experienced a surge after the GFC broke out. Under the government-led deleveraging moves, China's macro leverage ratio peaked at the end of 2017 at 241.2%, after which it stabilized, until it was driven up again by the COVID-19 outbreak to a new height of 270.1% at the end of 2020 (Figure 3).

As analyzed above, the surging leverage ratio made a large asset expansion possible and boosted China’s financialization, which had distributional effects, the most obvious of which were skyrocketing house prices and widened wealth and income gaps. This has also been accompanied by continuous rise in household leverage (mainly housing mortgage loans).

Second, higher value added of the financial sector.

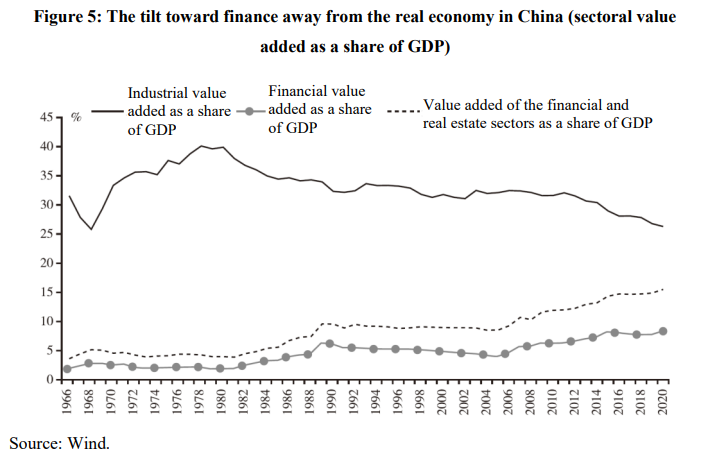

Value added of the financial sector as a share of national income has always been an important gauge when we discuss financialization and how it reshapes income distribution.

As seen in Figure 4, since the mid-1990s, the value added of the financial sector as a share of GDP in Japan and Germany stayed rather stable, if not slightly declined (except for a rise during 2000-07 amid prospering globalization); that in the United Kingdom surged during 2000-08 and fell back slightly after the GFC; that in the United States has stayed high, despite a short downfall in 2008 after which it picked up again.

In China, the value added of the financial sector as a share of GDP ballooned since 2005, peaking at 8.4% in 2015, above the U.K. and the U.S. level. While the estimation of this value is controversial because of different calculation methods and scopes applied, there is no deny that this proportion in China is a bit too high. The fact that it even exceeded the levels in the U.S. and U.K. reflects China’s financial catch-up and the general financialization trend.

The financial sector adds value by providing financial services. To a large extent, its value added is the cost paid by the real economy in exchange for financial services. The (abnormally) high value added of the financial sector as a share of GDP in China mirrors an economy and a distribution of income and wealth that are all tilting toward the financial sector away from the real economy (Figure 5).

Third, China emerging as a global pioneer in Fintech.

In recent years, emerging technologies represented by artificial intelligence (AI), big data (B), cloud computing (C), distributed ledger (D) and e-commerce (E) have become deeply integrated with the financial sector, boosting financial innovation and various new types of business such as mobile payment, online lending and intelligent investment advising.

China boasts nearly a billion Internet users, providing immense possibilities for Fintech applications. In 2019, 87% of the Chinese consumers used Fintech; as of the end of 2020, half of the 20 biggest platforms in the world were from China. Under the big platforms’ push, mobile payment burgeoned in China, with a market penetration of 86% today. China stands out as the largest market for Fintech- and platform-based credit business. In 2018 and 2019, big tech firms in China lent a total of 363 billion and 516 billion USD respectively, much higher than those in the U.S., which ranked number two globally (BIS, 2020).

China is one of the best in the world at Fintech. Chinese big techs are much more deeply involved in finance than those in some of the developed economies. Fintech has played a positive role in empowering the real economy and promoting inclusive finance. But it is a double-edged sword. When regulation fails to catch up, Fintech strays from its original purpose, making inclusive finance inclusive but not beneficial. For example, 90% of the funds lent to individuals and small- and micro-sized enterprises under joint loan programs were provided by banks, while Fintech companies, drawing on their technological edges in attracting borrowers, charge intermediary fees mounting to about one-third of borrowers’ total financing costs; sometimes the proportion can be up to two-thirds when commission fees or fees for excessive credit extension are collected as well.

II. CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Financial development and common prosperity are broad topics that cover a wide range of theories (mechanisms) and yield varying results in different studies. The rise of Fintech adds another dimension to the debate if not redefines financial development. This article has no room or intention to delve deep into each topic. It merely serves to provide a rough research framework by raising questions about the two subjects to demonstrate their interconnections, which hopefully could provide a guide for future research.

This article examines how financial development affects inequality from micro and macro perspectives: appropriate and orderly financial development alleviates inequality, whereas financial repression and over financialization exacerbate inequality.

The coexistence of financial repression and financial catch-up (as well as financialization) is a feature of financial development in China; the two factors are also the cause of current disparities in distribution.

Given this, financial development for common prosperity requires adhering to the primacy of the people’s livelihood, grasping the nature of finance, clarifying the positioning of finance, promoting financial reform and making important progress in the following areas.

1. Financial development should return to serving the real economy and avoid excessive financialization.

The coexistence of financial repression and financial catch-up is a “characteristic” of China's financial development; but neither an underdeveloped nor an overdeveloped financial sector is healthy for the economy. Financial repression leads to underdevelopment, credit discrimination, and financial exclusion; financial catch-up (when going beyond the proper level) leads to income transfer and a worsening of distribution.

(1) Reduce financial repression and promote market-based financial development.

① Allow the market to play a decisive role in the allocation of financial resources while reducing government intervention and eliminating financial repression. First, promote market-based capital allocation by improving stockmarket rules, hastening the development of the bond market, increasing the supply of effective financial services, and proactively and orderly promoting financial opening-up. The second is to accelerate market-based price reform in the financial sector by integrating benchmark deposit/loan interest rates with market interest rates, improving the efficiency of pricing in the bond market, and improving and fully utilizing the government bond yield curve as a pricing benchmark for reflecting market supply and demand.

② Enhance the flexibility of the RMB exchange rate. Maintain basic stability of the RMB exchange rate at a reasonable equilibrium level.

(2) Avoid diversion from the real economy or over-financialization.

Finance should return to its roots of serving the real economy and meeting the needs of economic and social development and the people. Financial innovation and development should focus on improving the effectiveness of serving the real economy and correcting unbalanced and insufficient development. Local governments should not regard financial sector expansion as a "political achievement" and avoid financialization that is beyond the stage of development. Financial regulation should be comprehensive and prudent to prevent excessive financialization.

2. Promote the healthy development of the real estate sector and strive to provide housing for all.

Housing is an important component of household wealth; the housing gap explains a large portion of the wealth gap among Chinese households. As a result, promoting the healthy development of the real estate industry and ensure people’s access to a secure home is a critical component of promoting common prosperity.

(1) Give a reasonable positioning for the real estate sector.

For households, houses are their base and most important property; for local governments, it is an important leverage for economic development; and for banks, it is important collateral and a "good" place to put credit. Real estate is critical in connecting finance and the real economy. In the future, the real estate industry will continue to be an important sector of the Chinese economy and a nexus that links finance and the real economy. Economic growth, improved livelihood, and common prosperity are all dependent on the steady development of real estate.

(2) Promote the healthy development of the real estate sector.

We should strive to reduce speculation in the housing market, implement city- and sector-specific policies, stabilize land prices, property prices and expectations, implement a long-term real estate market mechanism, meet household demand for high-quality housing, and promote the sound development of the real estate industry.

(3) Government should assume the responsibility of providing greater housing security.

To help households reduce their housing-related expenses and lowering their leverage ratio, the government should establish a housing security system pillared by public rental housing, subsidized rental housing, and shared ownership housing.

3. Protect farmers' land property rights and close the urban-rural divide.

Closing the urban-rural divide is a pivotal component of improving income distribution.

Rural people (rural areas) have made significant contributions to China's industrialization and urbanization and made great sacrifices in this process; this should not be repeated in China's modernization process. Helping farmers find work in cities could increase their income, but more importantly, the country should protect their land property rights during the modernization process.

To increase farmers' property income, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee devised a systematic top-level design for the transfer of "three types of land" in rural areas (i.e., collective land for business construction, farmers' contracted land, and homesteads). Rural collective land property rights are somewhat ambiguous, with ownership, contractual rights, and management rights being separated. Under such conditions, the difficult question of how to distribute land proceeds arises. The central issue in land reform is how to protect farmers' interests. For farmers, this may be their last chance to change fate.

If all land is marketed and capitalized, yet the income from land price appreciation has nothing to do with farmers, it will be a huge blunder and a missed opportunity to close the urban-rural income gap.

Therefore, in the revision of the Land Administration Law, as well as in the reform of the institutional mechanism for market-based land allocation, we should deepen the reform of the rural land system, and promote innovation in the way of transferring and exchanging homesteads, so as to better protect the land property rights of farmers and allow them to share in land price appreciation.

4. Develop inclusive finance to share growth dividends with low-income groups.

(1) Developing inclusive finance can make credit loans more accessible to low-income groups and SMEs.

The high cost, low efficiency, and low profit margin of inclusive finance create a conflict between commercial sustainability and public accessibility?—a significant barrier to inclusive finance. Inclusive finance should strike a balance between being "inclusive", "beneficial" and commercially sustainable. Therefore, on the one hand, we should implement various targeted measures to increase credit supply, drive down credit cost, and give more low-income groups and SMEs access to affordable financial services. On the other hand, we should strengthen R&D to break down technical barriers in the inclusive finance credit business and improve the commercial sustainability of financial institutions by improving service quality and lowering costs.

(2) Breaking the barriers to financial access to share the benefits of growth with low-income groups.

To broaden the channels for households to increase their income through interests, dividends, bonuses, rents and insurance, the government should adjust the entry thresholds to enhance the inclusiveness of the wealth preservation and appreciation functions of the financial and capital markets, so that low-income groups can share in the growth dividends.

5. Bear in mind the double-edged nature of Fintech and harness the power of Fintech to do good.

While a powerful tool for promoting financial inclusion, Fintech also brings issues such as digital divide, risk spillover, and data governance challenges. As such, it is critical to recognize its double-edged nature and focus on tapping into the potential of Fintech to do good.

(1) Bridge the digital divide.

This includes investing in digital infrastructure in rural and western China, strengthening interconnection and bridging the urban-rural digital divide, encouraging the customization of mobile financial products to the specific and most frequent needs of older adults, minorities and disabled people, and utilizing smart mobile devices to extend the reach of financial services to break the digital divide between groups.

(2) Regulate Fintech.

Fintech regulation and development are both critical. There should be a balance between equity, efficiency, and security to avoid a private rate of return that is significantly higher than the social rate of return. Fintech has the potential to contribute to common prosperity.

(3) Improve data governance.

Strike a balance between data protection and data sharing to maximize the potential value of data as a factor of production. In particular, breakthroughs should be made in the areas of data ownership, privacy protection, data sharing and anti-monopoly issues to ensure fair and reasonable distribution of proceeds from data assets.

This is an excerpt of the article published on Economic Perspectives, Vol. 12, 2021, reposted by C40 on its WeChat account on February 23, 2022. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the author. The viewpoints herein are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations.