Abstract: China needs to implement more proactive fiscal policy, and it has to resolve three key issues to that end: (1) How to deliver more tax and fee cuts and tangible gains to small- and medium-sized enterprises with mounting downward pressure on fiscal revenue? (2) With limited financing and lower fiscal revenue, how can the government maintain a proper intensity of expenditure if it does not increase deficit? (3) With limited fiscal deficit in support of infrastructure spending, how can local governments curb implicit debts while promoting ahead-of-schedule infrastructure investment? This article argues that deficit management is the major countercyclical adjustment tool, and calls on China to increase the deficit ratio and improve fiscal-monetary policy coordination to drive infrastructure investment and stabilize growth.

In 2022, the Chinese economy will battle pressures from contracted demand, supply-side shock and weakened expectations. In view of the multiple headwinds, policymakers have taken macroeconomic stability as the priority while striving to achieve growth. Having seen monetary policy adjustments already, the market is now more expecting more proactive fiscal policy moves.

Such expectation has been ignited mainly by three highlights in the policymakers’ language, which are “scale up tax and fee cuts,” “maintain the intensity of fiscal expenditure,” and “investment in infrastructure conducted ahead of the normal schedule.” These are exactly how the market defines “more proactive fiscal policy”, thus validating its expectation.

We believe the necessity of more proactive fiscal policy is beyond discussion; however, if China is to see true fiscal expansion in the above three aspects, it needs to break three major bottlenecks.

First, economic downturn is usually accompanied by reduction in fiscal revenue. In view of that, how to deliver more tax and fee cuts and tangible gains to small- and medium-sized enterprises?

Second, with limited financing and lower fiscal revenue, how to maintain a proper intensity of expenditure if the government does not increase deficit?

Third, with insufficient deficit allowed for in support of infrastructure spending, how can local governments, the major investor in infrastructure projects, strike a proper balance between curbing implicit debts and promoting ahead-of-schedule infrastructure investment?

More proactive fiscal and monetary policies are necessary to counter pressure from economic downturns. In the fiscal policy toolbox, tax reduction is more of a structural policy, while expanding fiscal deficit serves as the main countercyclical adjustment tool. Fiscal deficit is not a dreadful thing, but an important means to iron cyclical fluctuations. A higher fiscal deficit is totally within the scope of ability for China as the second largest economy in the world. Compared with signaling languages, the market hopes to see more proactive, practical and executable fiscal policy which is key to shoring up expectations.

BOTTLENECK 1: HOW TO DELIVER MORE TAX AND FEE CUTS WITH MOUNTING DOWNWARD PRESSURE ON FISCAL REVENUE?

Data from the Ministry of Finance of China shows that the country reduced taxes and fees by a trillion yuan in 2021, while a further cut was called for at the recent central economic working conference. However, with foreseeable downward pressure on the macroeconomy, fiscal revenue is also under strain. How to deliver greater tax and fee cuts with mounting downward pressure on fiscal revenue is the first bottleneck choking more proactive fiscal policy.

On the one hand, as China’s economic growth slows and its key sectors including real estate enter prolonged adjustments, reduction in the country’s fiscal revenue is almost irreversible, squeezing the space for further tax and fee cuts. Fiscal revenue, fluctuating in tandem with macroeconomic performance, is the financial foundation for the government to fulfill its public duties. For several years before the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, China’s economic growth experienced continuous decline, which, in addition to several rounds of major tax and fee cuts, has already put the country’s fiscal revenue under huge strain. In 2019, China recorded a growth of general public budget revenue of 3.8%, the lowest since 1987, and a growth of tax income of a minuscule 1%. The downward pressure only aggravated in 2020 amid the pandemic’s blow, with the general public budget revenue descending by 3.9% and tax income, by 2.3%.

The high growth of fiscal revenue in 2021 was mainly owed to the base effect and the price effect, and is hard to sustain. As shown in the figure below, there is a strong positive correlation between growth of fiscal revenue and PPI in China, which is because China’s taxation system is mainly characterized by indirect taxes with economic turnovers as the tax base, and so the price hike of commodities contributed largely to the increase in tax revenue. This is the key factor that pushed up China’s fiscal revenue growth last year. As commodity prices stabilized, we were already seeing the monthly year-on-year (y-o-y) growth of taxation revenue enter the negative territory in September 2021, further dipping to -11.2% in November and -16.1% in December.

In other words, the fast growth of fiscal revenue that we saw in 2021 may have already concluded, and going forward fiscal revenue will step back on its long-term trajectory of steady, low growth.

Figure 1: Growth of general public budget revenue and PPI (%)

The sluggish real estate sector could further add to fiscal revenue pressure, because it contributes much more to taxation than it does to GDP. During 2011-19, the total tax revenue collected from the real estate sector rose from 866.6 billion to 2.5027 trillion yuan at an annual rate of 12.5%, and its share in total tax revenue increased from 9.7% to 16.2%, much higher than its proportion in GDP of 7.3%. In terms of value-added tax (VAT) and corporate income tax, the real estate sector contributes to 11.5% and 16.7% of national total, respectively, both higher than its contribution to total GDP. In addition, in 2019, 88.9% of total land VAT, 63.4% of total contract tax and 27.6% of total house property tax in China came from the real estate sector. Collection of these taxes rely heavily on the real estate sector. Since business tax has been replaced with VAT, the real estate sector has been taxed at a rate of roughly 37%, which means for every 100 yuan of value added, 37 yuan of tax has to be paid.

As for revenues from land transfers, according to accessible data, in 2017 the real estate sector contributed to as high as 91.8% of total proceeds from land transfer. Based on this and the historical level of taxation on the real estate sector, in 2020, fiscal revenue from the real estate sector (tax plus land transfer proceeds) accounted for over 35% of the government’s balance sheet (general public budget plus government fund budget).

Considering this, the reduced, if not negative, growth of the real estate sector will place greater downward pressure on fiscal revenue. Since July 2021, revenue from real estate-related taxes has been growing negatively (Figure 2); during August and November, the proceeds from local land transfers grew at -17.5%, -11.2%, -13.1% and -9.9%, respectively.

Figure 2: Monthly y-o-y growth of tax revenues from the real estate sector (%)

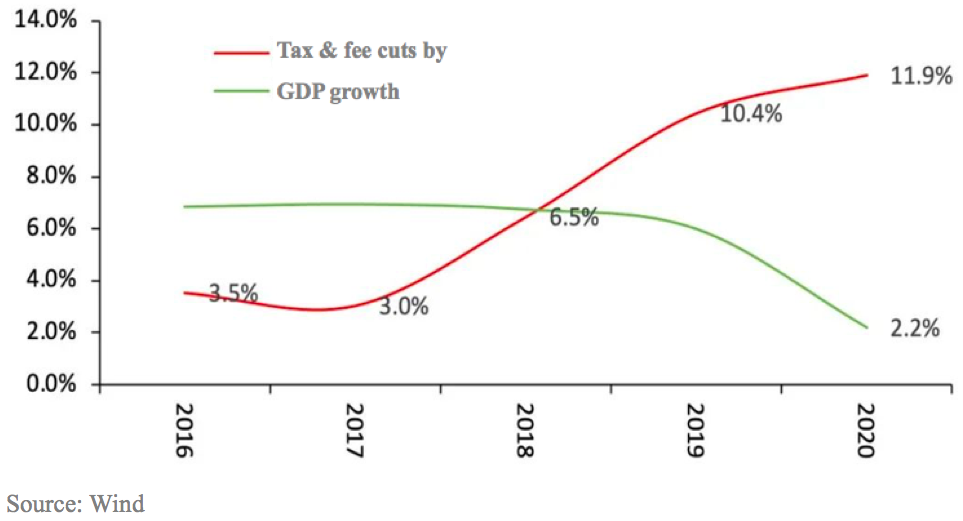

Tax and fee cuts is more of a structural policy, and data suggests that its role in driving economic growth has been fading. We have calculated by how much taxes and fees were reduced throughout the years with total budget revenue excluding proceeds from land transfers as the base, and compared it with economic growth (Figure 3). As shown, taxes and fees were cut by 3.5% in 2016, rising to 11.9% in 2020, while economic growth slid from 6.9% to 2.2%. Even if we exclude the effect from the special year of 2020 and assume the year recorded a growth of 6.1%, same as in 2019, it remains clear that the role of tax and fee cuts in driving economic growth was weak.

Figure 3: Tax and fee cuts versus economic growth (%)

An important reason behind this is that China’s current taxation system is dominated by indirect taxes. Massive tax and fee cuts actually do more good to big upstream businesses that contribute more to turnovers, while small- and medium-sized enterprises shouldering the heaviest burden benefit much less. Take VAT for example. Theoretically, the special deduction rule of VAT makes it very hard for downstream small- and medium-sized businesses with little bargaining power to pocket all additional revenues from tax cuts, because not all businesses can keep the level of price including tax unchanged when the tax rate is lowered. This means a sector may not necessarily take all the benefits from tax cuts. Whether it can do this depends on its bargaining power, or the price elasticity of demand of its products.

As the VAT rate comes down, businesses with weaker bargaining power tend to reduce their price in order to maintain market shares. And if we look at the data, in 2019, inclusive tax and fee cuts for small- and medium-sized enterprises were 282.3 billion yuan, accounting for only 11% in the total reduction amounting to 2.36 trillion yuan.

The analysis above indicates that there may be a more reasonable interpretation of “scaling up tax and fee cuts,” which is that “scaling up” means while maintaining stable fiscal revenue, China seeks to improve the efficacy of tax and fee cuts through structural arrangements, and make taxation more streamlined, transparent and coherent in order to stabilize business expectations and deliver more tangible benefits to them. The fundamental goal of tax and fee cuts is to revitalize market participants, but at the same time it’s important to keep in mind that taxation is the most stable and legitimate source of fiscal revenue. To ensure normal functioning of the government and stem improper behaviors of local governments to obtain disposable income, it’s critical to improve the efficacy of tax and fee cuts while maintaining tax stability. Particularly, given the huge strain facing local governments, pressing ahead with tax and fee cuts could breed improper behaviors such as disguised or ahead-of-schedule tax collection that could harm businesses and the government’s credibility.

BOTTLENECK 2: WITH LIMITED FINANCING AND LOWER FISCAL REVENUE, HOW CAN THE GOVERNMENT MAINTAIN A PROPER INTENSITY OF EXPENDITURE IF IT DOES NOT INCREASE DEFICIT?

No matter how tax and fee cuts are delivered, there is almost no doubt that China’s fiscal revenue will fall. There is the fiscal rule to “determine expenditure based on the level of revenue.” Then, without a sufficient level of fiscal deficit, how can the Chinese government maintain a proper intensity of expenditure? This is the second bottleneck to more proactive fiscal policies.

To answer this question, we first need to define an “proper intensity” of fiscal expenditure, which has to be measured against the need for maintaining economic growth. According to market expectations, we assume the actual GDP growth target for 2022 to be 5.5%. That would mean the government consumption expenditure should grow at 5.5% or above, or it would drag GDP growth.

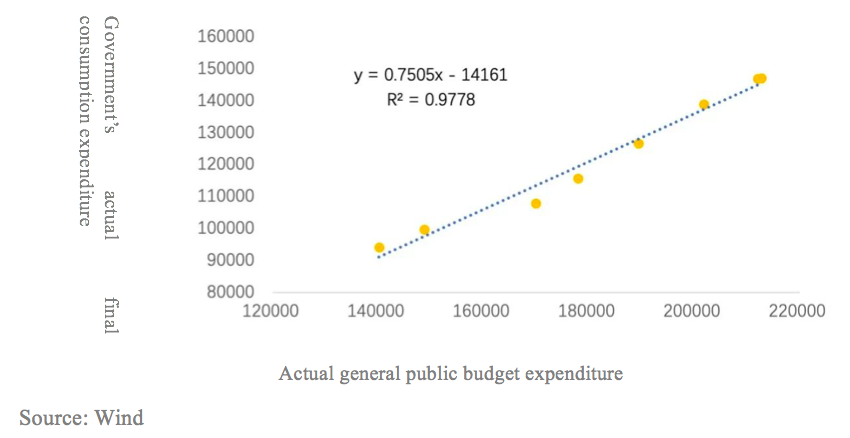

We first need to identify the quantitative relationship between the growth of fiscal expenditure and the growth of government consumption expenditure in GDP calculation, after which we work backward and reach a growth rate of fiscal expenditure necessary for enabling a growth of government consumption expenditure of 5.5%. Under the expenditure approach for GDP calculation, the government purchases the service of civil servants and other services and products when it spends money, and such spending can be deemed consumption to be included in GDP. After adjusting for price change, we discover a relatively stable relationship between the government’s final consumption expenditure and general public budget expenditure under the expenditure approach (Figure 4).

According to our estimates, in 2022, the general public budget expenditure needs to reach a nominal growth of 7.3% to enable a real growth of government consumption expenditure of 5.5%.

If we further consider the drag on GDP by sluggish household demand, for the government to close this gap as a result of reduced household consumption by increasing its own spending, the general public budget expenditure has to reach a nominal growth at or above 15%.

Figure 4: Relationship between the government’s actual final consumption expenditure and the actual general public budget expenditure

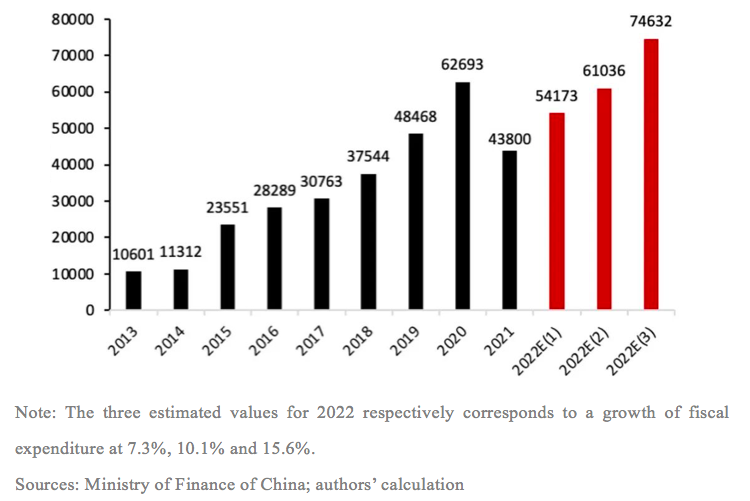

Furthermore, let’s assume that the growth of general public budget revenue in 2022 is the same as back in 2019, at 3.8%, which is quite optimistic given the mounting downward pressure on it. Given that, a growth of general public budget expenditure at 7.3% and 15.6% would respectively indicate a gap of 5.42 trillion and 7.46 trillion yuan. If 2020 is an extreme, it recorded a fiscal expenditure gap that was only 30% higher than in 2019, and this is probably the highest annual speed at which the gap can grow. If we apply the 30% rate to the gap in 2021 of 4.38 trillion yuan, then the maximum possible gap in 2022 would be 5.7 trillion yuan, and the corresponding growth rate of fiscal expenditure would be 8.3%.

To sum up, China’s general public budget expenditure will have to increase at 7.3% or above to enable a real GDP growth of 5.5%, and that would mean a revenue-expenditure gap of 5.4 trillion yuan, otherwise it would drag GDP growth. Even if more proactive fiscal policies are implemented, the growth in expenditure is not expected to top 8.3%, which indicates a fiscal gap of 5.7 trillion yuan.

Figure 5: Gap between actual general public budget revenue and expenditure (?00,000,000 yuan)

The gap can be filled with either fiscal funds carried over from the past year, or with fiscal deficits of the current year. Some say that the surplus from the budgeted funds for 2021 could be used to finance fiscal expenditure in 2022, but they have overestimated the level of China’s fiscal surplus at the moment. In the budget implementation report, budgeted “expenditures” of government funds do not include off-budget funds that were used to narrow the actual fiscal deficit. For example, in 2020, the actual revenue-expenditure gap of government funds were 2.5 trillion yuan higher than budgeted, but this year, a total of 2 trillion yuan, 1.7 trillion yuan higher than budgeted, was transferred from government funds to the general public budget. That means a large proportion of the 2.5 trillion yuan of “surplus” of government funds has actually been “spent”. Therefore, a growth of fiscal expenditure of 7.3% will mostly be financed by deficits, with a corresponding deficit ratio of approximately 5%.

BOTTLENECK 3: HOW CAN LOCAL GOVERNMENTS CURB IMPLICIT DEBTS WHILE PROMOTING AHEAD-OF-SCHEDULE INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT?

The Ministry of Finance reiterated its dedication in December 2021 to “curbing additional implicit debts while addressing existing ones.” An estimated 60% of infrastructure funds in China are raised by local state-owned enterprises (SOEs), especially by urban investment companies whose main business of municipal construction investment account for the largest proportion in total infrastructure. Their lackluster performance has been the major drag on general infrastructure investment in recent years.

To be specific, the sluggish infrastructure investment in China is characterized by a slowdown in municipal investment led by local SOEs or local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), whose motivations are stemmed by the drive to resolve implicit debts. Tackling implicit debts of local governments is a complicated task. Local governments facing acute debt risks hope to distinguish between new and old debts for the time being so that they can address implicit debts first. Hence, the slowdown in municipal or general infrastructure investment is a result of the change in the investment willingness of LGFVs under pressures from both reduced revenue and debt risks. Unnecessary budget expenditures on municipal projects or tourist site construction are among the first to be cut when downward pressure on fiscal revenue mounts; while for off-budget spending, against the government’s push to resolve local implicit debts with increased regulatory restrictions on LGFVs, public facility management including municipal projects under the LGFV’s charge and tourist site construction has become the biggest drag on total infrastructure investment.

Under such circumstances, how to strike a proper balance between curbing implicit debts and promoting ahead-of-schedule infrastructure has emerged as the third key bottleneck to more proactive fiscal policy. Two issues have to be addressed to break it.

One is how can “resolving implicit debts” and “issuing new debts to finance infrastructure projects” stand apart from each other. The policy purpose is obviously to explore a more sustainable model for financing infrastructure to replace the previous risky one that relies on local financing vehicles. But in practice, local governments’ staffs usually work on both tasks at the same time, and for them the first task is more stressful. It’s hard to find a better financing model in a short time. They may have to choose between continuing or stopping borrowing, and most of them may end up with the latter.

The other is how to use special debts more efficiently to fully play their due role in financing infrastructure projects. Under the current regime, special debts, usually underused, have yet to serve as a decent source of disposable financing for local governments. Special debts were well-intentioned, but they are only provided to projects with both returns that could cover the principal plus interest and good performance. Few projects meet the standards, leaving many of the special debt funds unused. In addition, many of the projects were too poorly-managed or -endowed to produce satisfactory returns, and it’s always the general public budget funds that pay their bills. Thus, to use special debts more efficiently, it’s important to lower the thresholds of special debts and place more of the administrative restrictions on their usage instead of the cash flows, so that it can truly stimulate infrastructure investment.

INCREASING THE DEFICIT RATIO IS THE BEST WAY FOR CHINA TO IMPLEMENT MORE PROACTIVE FISCAL POLICIES

Amid economic downturns, macroeconomic policymakers should implement more proactive fiscal and monetary policies. Among available fiscal policies, tax cut is more of a structural measure, while deficit-based management serves as the main countercyclical adjustment tool. While studying how to use tax cuts or special debts better, it’s critical to allow for a bigger fiscal deficit, coordinate fiscal and monetary policy more efficiently, and give full play to the government’s role in boosting financing and stabilizing growth.

Fiscal deficit is not dreadful. Deficit management is an important tool of countercyclical adjustment. China, as the second largest economy in the world, has the ability to bear a higher deficit ratio. Compared with signaling languages in official documents, the market hopes to see more proactive, practical and executable fiscal policy which is key to shoring up expectations.

This article first appeared on CF40’s WeChat blog on February 9, 2022. This translated version has not been reviewed by the authors themselves.