Abstract: Platform economy brings benefits such as promoting service coverage, employment, innovation, and economic growth. But this unique form of digital economy also poses challenges to market fairness, income distribution, and digital governance. In the future, governance of platform economy should focus on orderly development of the sector and common prosperity.

In response to the key issues in the development of platform economy in China, the National School of Development of Peking University launched a program on “Platform Economy: Innovation and Regulation”. The research consortium consists of over two dozen members from the School of National Development, the School of Law, the School of International Relations, and partner universities. After six-month extensive research and communications, the team has come up with some preliminary findings.

I. WHAT IS PLATFORM ECONOMY?

Platform economy is a unique form of the digital economy.

The term “digital economy” was coined by Don Tapscott in his 1996 bestselling book, The Digital Economy: Promise and Peril in the Age of Networked Intelligence, and has since taken on various nuanced meanings.

In the Statistical Classification of Digital Economy and Its Core Industries released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China in 2021, the digital economy is defined as “a series of economic activities reliant on data as the key factor of production, based on modern information networks, and backed by the effective use of ICT to improve efficiency and economic structure.”

As a special form of the digital economy, the platform economy relies on online infrastructures such as cloud, network, and terminal to facilitate transactions, transmit contents, and manage processes through digital technology tools such as AI, big data, and blockchain.

Platforms are not novel, but thanks to the application of new technologies, digital platforms have overcome many of the constraints that traditional platforms faced in location, time, transaction scale, and information communication to reach a whole new level of scale, substance, efficiency, and impact.

II. CLASSIFICATION OF PLATFORMS

Platforms have become a part of our daily lives.

Platforms can be divided into two categories based on their functions: transaction facilitators and content conveyors. Transaction-enabling platforms are designed to deliver transaction information. E-commerce, payment, online car-hailing, and food delivery platforms are just a few examples. Content-transfer platforms, which include social networking and short video platforms, deliver news, music, opinions, ideas, and other contents,

We believe that platforms will develop even more extensively, especially in education, healthcare, culture, media, home, wear, and transport.

It is worth noting that the current platforms are mostly related to personal use and consumer Internet. As 5G drives the application of the Internet of Everything with high throughput and low latency, we expect to see more platforms based on the industrial Internet, the Internet of Things, or supply chains.

Our study employs one of the many classification methods of platforms; there should be different types of platforms identified through different analyses.

China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) recently released a draft guidelines on the classification of Internet platforms, which sets specific benchmark for mega-platforms, defining them as those valued above one trillion yuan. Alibaba, Tencent, ByteDance, Meituan, and Pinduoduo have all met SAMR’s mega-platform standards.

III. DEVELOPMENT OF PLATFORM ECONOMY

Taobao is the first platform in China. It was launched in June 2003, right after the SARS epidemic was put under control in May. Taobao is not Alibaba’s first attempt at transaction intermediation business, but it is the most successful one.

However, the development of China’s platform economy started in 2008. The period 2008-2015 witnessed its explosive growth that featured ever-mushrooming startups and accelerated innovation; 2015-2019 were characterized by M&A and reorganizations driven by intensified competitions and risks; after 2020, particularly in 2021, the platform economy encountered a sweeping cleanup as the Chinese government sought to address financial risks, potential monopoly issues, and data security issues, even national security issues in the sector.

In particular, China’s platform economy has been picking up pace since the outbreak of COVID-19.

I often mention the "broken window theory". In fact, there are two broken window theories, one in political science and the other in economics.

The broken window theory proposed by American political scientist James Q. Wilson states that if some windows on a street are broken, it encourages further crimes and disorder; that is, a bad environment worsens public order. A daily life analogy is that, if there is already a lot of rubbish in a place, it may be less psychologically taxing for you to join in the littering and you may just well do so; but if the place is clean, you are far less likely to leave your trash there. This is the broken window theory in political science and criminology.

The broken window theory in the economic field was introduced by French economist Frédéric Bastiat. It roughly means that destruction could potentially produce certain economic opportunities, just like broken windows create the need for repairs and replacements.

The economic broken window theory can explain the rapid growth of the digital and platform economy during the pandemic. When city lockdowns and quarantines become the main means of pandemic control, the digital economy stands out because of its unique feature—contactless transactions. Meanwhile, digital technology has aided in the identification and control of risks through travel codes, health codes, and other tools that we now frequently employ.

After more than a decade of development, China's platform economy has made significant achievements even on a global scale. The world’s platform economy or digital economy is generally divided into three parts: the United States, China, and other parts of the world. Since the rest of the world is dominated by American companies, there are essentially two major players: the most developed economy, the US, and the largest developing economy, China.

The scale of China's digital economy reached 35.8 trillion yuan in 2019, accounting for 36.2% of GDP, according to China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). Data from the China Academy of Information and Communication Technology (CAICT) show that, of the 74 digital platform companies with a global market value of over US$10 billion, 35 are based in the US and 30 in China. The value of digital platforms in the US amounts to $6.65 trillion, accounting for 74.1% of the global total; the value of digital platforms in China is $2.02 trillion, accounting for 22.5% of the global total. When you add up the values of the two countries, it is clear that the US and China are playing a duet.

"Unicorn" is another popular concept in the discussion about platform economy. It refers to companies less than 10-year old with a valuation above $1 billion. Of the top 10 unicorns in the world as ranked at the beginning of 2020, China and the US each accounted for five. The five Chinese unicorns are the Ant Group, ByteDance, Didi Chuxing, Lufax and Ali Local Life.

It is marvelous for a developing country to stake out a major place in the digital and platform economy.

The interesting questions are: How did China grow into such a large size? What exactly are the strengths that have enabled us to develop to such a level? Here we give a summary of China's strengths.

Advantage 1: A huge market

A huge market means large consumer base, which enables innovation and allows platform companies to fully exploit their exclusive advantages.

Advantage 2: Lax protection of rights

China’s protection of personal rights and data privacy is not stringent enough, which, in a certain sense, encourages innovation. But it has also caused many headaches that we now have to deal with.

Advantage 3: Market separation

China’s market is somewhat separated from foreign markets that are dominated by American companies, which occupy only a small share in China. Although market separation gives Chinese platforms space to grow, it is not without problems.

Despite the above-mentioned advantages and the towering size, Chinese platform companies do not stand out as far as technology is concerned.

IV. BASIC FEATURES OF PLATFORM ECONOMY

Platform economy has five basic features.

Feature 1: Economy of scale

Once a platform is established, expanding its services does not significantly increase its marginal cost. In other words, higher production corresponds to lower average costs, which is known as the long tail effect. Because it is easy to expand with low marginal costs, larger companies tend to be more productive and competitive.

Feature 2: Economy of scope

Producing multiple products at the same time costs less than producing each product separately, so companies tend to go into different businesses because producing a range of products is more efficient than producing a single product. It is common to see such platforms in China. For example, an e-commerce platform could also engage in payment business and more, thanks to the economy of scope.

Feature 3: Network externalities

This is primarily the economy of scale on the demand side, i.e. the more consumers there are, the higher the value of use per capita. There are two broad explanations for such externalities: (1) When more consumers come and enlarge the market, everyone can enjoy more and better services; Or (2) when the market expands, it further encourages innovation for new services and products.

Feature 4: Dual (multi)-sided market

Platforms have to serve multiple parties at the same time. In the case of a takeaway platform, for example, it has to deal with restaurants, consumers, as well as deliverymen. The pricing structure for each party directly affects the revenue of the platform. Therefore, when pricing for one party, the platform needs to take into account the external impact on the other party.

Feature 5: Big data analysis

The most prominent differences between digital platforms and traditional platforms are scale, speed, and data that allow digital platforms to break the limits of time, place, and industry and become service platforms of enormous scale. Digital platforms have huge advantages in the transmission, analysis, collection and use of information.

V. BENEFITS FROM PLATFORM ECONOMY

The technology-driven platform economy could bring many economic benefits.

Start with digital technologies. What has driven the platform economy boom since 2008? An engine powering the global digital economy boom is the 4th industrial revolution that we are currently going through, characterized by blockchain, the Internet, AI, big data, and cloud technologies.

The technological features of platforms can bring multiple economic benefits, which can be distilled into improved scale, efficiency and experience, and reduced cost, risk and contact (with some transactions totally contactless). These are mainly manifested in several aspects.

First, digital technology platforms help improve social governance. During the COVID-19 outbreak, digital technologies represented by the health code and travel code have been widely deployed in China, boosting governance efficiency and capacity. In addition, Guangdong and Zhejiang province have introduced digital public service platforms which have been playing a significant role in improving local governance.

Second, the platform economy can drive economic growth. We have analyzed the digital economy’s contribution to China’s economic and productivity growth. ICT development, ICT-intensive manufacturing and ICT-intensive service are the three main economic sectors which combined can be roughly defined as China’s digital economy. During 2012-18, the three sectors contributed to 74.4% of China’s total GDP growth. According to data from the MIIT, digital economy accounts for 36% of the country’s GDP, but its actual contribution to growth is expected to be much higher.

Third, the platform economy has strong long tail effect, capable of serving myriads of customers. There are hundreds of millions of active users on e-commerce, payment, social and short video platforms in China. Such a large user base is unimaginable in the traditional economy because it was simply infeasible. The platform economy has enabled long tail services targeting the ordinary people. It has also made inclusive finance possible.

Fourth, the platform economy has contributed to employment growth. Its boom has created a vast number of jobs, including online retailers, deliverymen, logistic service providers, etc. For example, Alibaba’s major e-commerce platform houses 53.73 million online sellers; Didi adds to 13.6 million job posts; and Meituan employs a total of 2.952 million deliverymen. These people work on a flexible basis, and the barriers to entry are low. In this sense, these platforms have served as new yet very important sources of employment, contributing significantly to a healthy labor market.

Finally, the platform economy can help boost innovation. In addition to their own innovative activities, platforms also serve as the incubator for the businesses that they host, proving them with training and supports. This, when done properly, will greatly facilitate business innovation.

I would like to highlight three things related to all these benefits that the platform economy can bring.

First is the inclusiveness of digital finance.

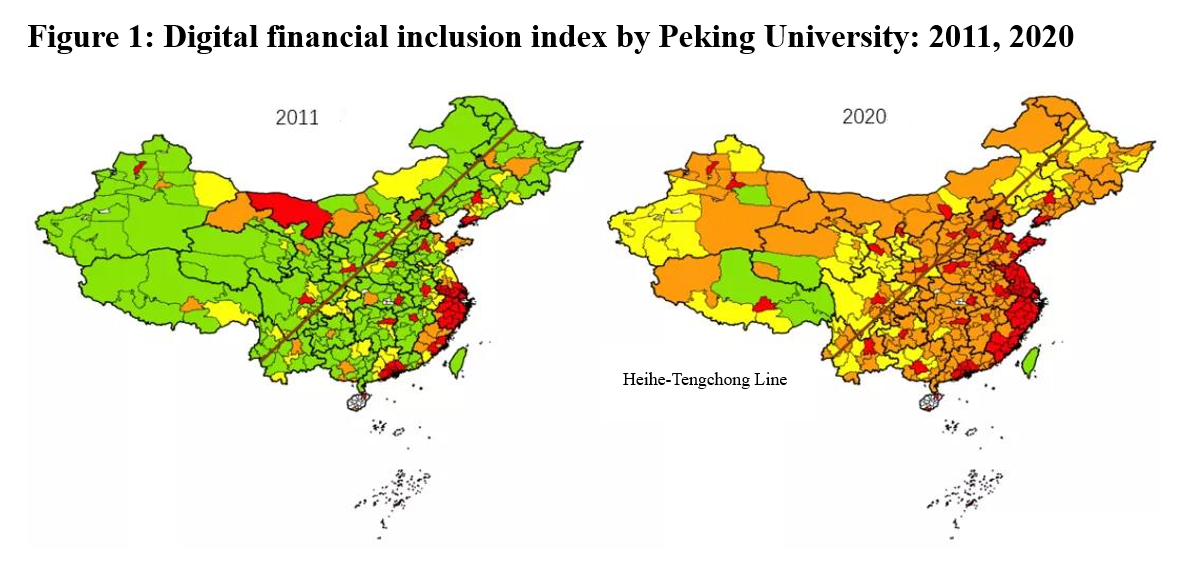

The two maps come from a research we have done at the Institute of Digital Finance (IDF), Peking University. We use different colors to indicate the level of financial inclusion driven by digital technologies in various cities across China. Red represents the regions with the highest level of financial inclusion, followed by orange, yellow and green. The left-hand side picture is for 2011; the right one is for 2020.

It’s clear that in 2011, only a small number of cities in Southeast coastal areas had a high level of financial inclusion; but in 2020, the regional gaps have remarkably narrowed as shown by the colors.

Let’s give a simple example to illustrate what this evolving landscape of financial inclusion means. In the past, remote inland areas especially inland borders hardly had access to any decent financial service; but today, with digital finance reaching almost every corner of the country, you can enjoy similar level of financial services wherever you are as long as you have a smartphone with signal.

Enabling the inclusiveness are the digital technologies and platforms. A platform has three core elements: cloud, Internet and terminals. With these elements available, similar level of financial services is at your fingertips anywhere in the country. This is a huge breakthrough.

Second is the management of big tech-induced credit risks.

Digital platforms assess the credit risks of the customers they have connected, based on which they issue loans, especially to small- and medium-sized businesses.

Big tech platforms and big data are the two pillars supporting solutions to problems with customer acquisition and risk control.

The main edge of big tech platforms is their ecosystem: they acquire customers via the long tail effect, who leave digital footprints with every online behavior such as shopping, social interaction and watching short videos. These footprints then amass to form big data, based on which the platforms can assess credit risks and issue loans. Platforms can also enhance debt repayment management via the ecosystem. Many online banks such as MYbank and WeBank are issuing loans to tens of thousands of borrowers under such model, and generally they have managed to contain the non-performing loans ratio at a relatively low level.

Such business model has attracted attention from international organizations especially in 2020 amid the pandemic. Last year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the IDF and CF40 jointly held a seminar on big tech credit business models. The IMF was intrigued by the online lending model which continued to operate when the pandemic and related control measures had paralyzed almost all banks. This is very remarkable innovation.

Third, the digital platform boom can add to macroeconomic stability in China.

Figure 2 shows two lines. The red one indicates the producer price index (PPI), namely the price of major commodities like raw materials, coal and iron as well as other investment goods. PPI has long been volatile. China’s PPI has been quite so recently due to instabilities in the global commodity market. However, CPI as shown with the blue line experienced structural changes around 2013. Before 2013, it evolved almost in tandem with PPI, but after that it has become quite stable.

What has led to such structural change of the CPI? Our research shows that the main reason behind is the fast development of the digital platform economy since 2013. The booms in e-commerce, mobile payment and logistics have significantly promoted nationwide market integration, smoothing out CPI fluctuations in the process.

For example, according to the advertisement of a used car dealer, it offers used cars from around the country, and buyers can choose cars from the place with the lowest price level. Such business model will, to a certain extent, help unify the price nationwide, improve market integration, and make the aggregate inflation less volatile. This is a very interesting and unexpected change.

VI. PROBLEMS WITH PLATFORM ECONOMY

Platform economy has brought problems along with benefits.

Problem 1: Governance

Among the three major players in a market economy, businesses are operating entities, the market matches transactions, while regulators are in charge of supervision. But this “division of labor” is blurred in platform economy because a platform can serve the functions of the three at the same time. A platform is a business, so we can say it’s a new type of economic entity.

There are occasions when the three roles come into conflicts. That also happens with traditional transaction platforms such as department stores and farmers’ markets, but digital platforms are different because of their large scale and high speed which enable them to provide many personalized services.

This could incur problems including unfairness and injustice in service provision, such as in online traffic diversion and search prioritization. There have also been platforms in other countries trying to reshape public opinion or even intervene in elections.

How to balance between efficiency and fairness in the platform economy is an issue to be addressed.

Problem 2: Innovation

All platforms start from and grow with innovation. But when they have reached a certain scale, can they remain innovative? Many mature platforms, with abundant cash flows, have chosen to acquire a large number of innovative startups to reduce market competition. Such “killer acquisitions” risk stifling innovation.

Many platforms “burn money” to achieve market dominance. Some of them have made it, such as Didi, while others have failed, such as Mobike. If we want to make sure that platforms sustain as a source of innovation, we first need to figure out how exactly they affect innovation.

Problem 3: Income distribution

Platform services have long tail effect. Platforms reduce the threshold for employment, and thus are highly inclusive in terms of job creation and service and product provision. In this sense, it seems platforms can help improve income distribution.

However, while creating new jobs related to online business, platforms have also replaced many offline traditional jobs. Although in aggregate the jobs they add may have outnumbered the jobs they wipe out, there is no deny that many have lost their livelihoods amid the platform economy boom. Can they weather through this? Can they find new jobs?

Moreover, do platform service providers, especially deliverymen, have decent income, welfare and working conditions? Another issue which calls for attention is the over-concentration of wealth as a result of the economy of scale / scope that platforms have generated during their development.

A question has thus emerged. Does the platform economy improve or worsen income distribution?

Problem 4: Fair competition

While providing businesses with new places and opportunities for competition, platforms face very common and fierce competition among themselves. However, is it possible for a platform to use its economy of scale or economy of scope to increase its own market power and the sunk cost of newcomers to reduce competition?

"Choose one platform between two" is a strategy that is often discussed. If this strategy is unreasonable, why is it?

Problem 5: Data algorithm

One of the reasons for the relatively rapid development of China’s platform economy is the insufficient protection of personal rights and privacy. Of course, the situation has been improving.

While bringing about abundant opportunities for innovation and services, big data also gives rise to a number of prominent problems such as data infringement, especially the violation of privacy.

Participants of many platforms, including taxi drivers, deliverymen and consumers, often have the feeling that they are controlled by algorithms. In his book Outnumbered: From Facebook and Google to Fake News and Filter-bubbles – The Algorithms That Control Our Lives, the Swedish mathematician David Sumpter explained that this is a global phenomenon.

While helping the platform reduce information asymmetry, big data increases the information asymmetry of platform participants, causing problems such as price discrimination. So, where is the boundary of using data algorithms to implement differentiated pricing?

Problem 6: International challenge

As mentioned earlier, there is a special reason for the rapid development of platform economy in China, that is, the Chinese market is relatively isolated from the international market. But in the future, whether being voluntary or forced, Chinese digital platforms will participate in international competition sooner or later. Therefore, China’s regulation not only needs to consider the relatively laggard technological development of the country’s platform economy, but also has to be prepared to align with international rules in the future.

Europe and the United States have already taken active steps in this regard. The United States’ demands for digital trade rules include the free cross-border data flow, non-localization restrictions, the abolition of digital taxes, intellectual property protection, etc.; the European Union advocates the free cross-border data flow, consumer privacy protection, antitrust and digital taxes, etc.

Since China’s platform economy will definitely take part in international competition in the future, how should China participate in the formulation of international rules? This is a problem we cannot avoid.

VII. ANTITRUST AND CONTESTABILITY

Recently, discussion of anti-monopoly policy has gained much attention in China, but in fact this is also a major topic in the United States as well.

The US antitrust policy has gone through several stages. The first is the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which outlaws any “monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy or combination to monopolize”. At that time, the formation of some large companies, such as oil companies and steel companies, attracted intense attention. In the early twentieth century, the United States tried to distinguish between "good" and "bad" trusts (a form of monopoly), but it was difficult to draw a precise distinction. In 1911, the United States split up the Standard Oil Company. At that time, Louis Brandeis, an associate justice on the US Supreme Court, was a famous critic of bigness which he viewed as both an economic and a political problem. Later, the Chicago school of economics viewed monopoly from the perspective of consumer welfare. The core of their approach is to look at prices—if the price is lower, it is good for consumer welfare and should not be treated as a serious problem of monopoly; but if a monopoly controls prices and infringe on the interests of consumers, it can be a severe issue. But lately, there has been a return to the Brandeisian view of “big is bad” in the United States, represented by the group known as the New Brandeis School, who believe that in addition to economic efficiency, competition and economic democracy should also be valued.

Based on the evolution of anti-monopoly policies in the United States over the past century, we find that anti-monopoly policies are often related to three economic factors: first, the slowdown of economic growth; second, the increase in industrial concentration; third, the deterioration of income distribution. In other words, when these three situations emerge, the public’s dislike towards big companies usually grows.

Actually, today’s China also sees the mentioned three economic factors to some extent. China's growth rate has slowed down, industry concentration has increased, and income inequality has been aggravated.

The Gini coefficient shows that with China's accession to the WTO, the inequality in income distribution has increased in the country. Of course, the background then is that China had just turned away from the previous planned economy, and the government was advocating that “l(fā)et some people to get rich first”. Although that could motivate hard work and innovation, and increase economic vitality, it has also aggravated income inequality. China’s actual Gini coefficient declined after the global economic crisis, but has rebounded in recent years. Generally speaking, it has stayed at a relatively high level.

In the recent two years, governance of platform economy and anti-monopoly has become a policy priority. The Recommendations of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Formulating the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-term Goals for 2035 clearly defined the healthy development of the platform economy and the sharing economy as an important means of cultivating strategic emerging industries. In early 2021, the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council issued the Anti-Monopoly Guidelines on Platform Economy. On November 18, the Anti-Monopoly Bureau of the State Administration for Market Regulation was officially established.

In the future, how should the platform economy develop? Current policies emphasize better governance, rather than purge or crackdown. We believe that the purpose of governance is to ensure orderly development and common prosperity.

One question that cannot be avoided is how to decide or define monopoly? Traditionally, market share is the key indicator for monopoly. However, this method has failed with the platform economy, because the basic characteristics of platform economy are economy of scale, economy of scope, and a series of network externalities, which means that "big" is an intrinsic feature of successful platforms. Therefore, is market share a suitable indicator for telling whether a digital platform exercises a monopoly? We think it is worth further discussion.

For the platform economy, our research team prefer to use the concept of “contestability”. Contestability theory was put forward by American economist William Baumol in 1982. It is a theory on how to achieve full competition under conditions of economies of scale. The key lies in the level of sunk costs for market entry and exit. Therefore, contestability means potential competitive pressure. A platform may occupy a relatively large market, but it also faces high pressure of competition.

For example, in 2013, the share of Alibaba’s Taobao and Tmall in China’s e-commerce market was approximately 92%, and by 2020 it had fallen to 42%. In seven years, the market share fell by 50%, indicating the e-commerce market is very active. Although Alibaba held a high market share in 2013, it did not actually have an absolute monopoly. The entry of new platforms has continuously squeezed its market share.

Therefore, we believe that one should not statically look at the market share when deciding whether a company exercises monopoly. The most important thing is to see whether the barriers to enter the market and the sunk costs for newcomers are low enough. As long as the barriers are low, the market is contestable. Even when a company enjoys a large market share, it is difficult for it to completely monopolize the industry.

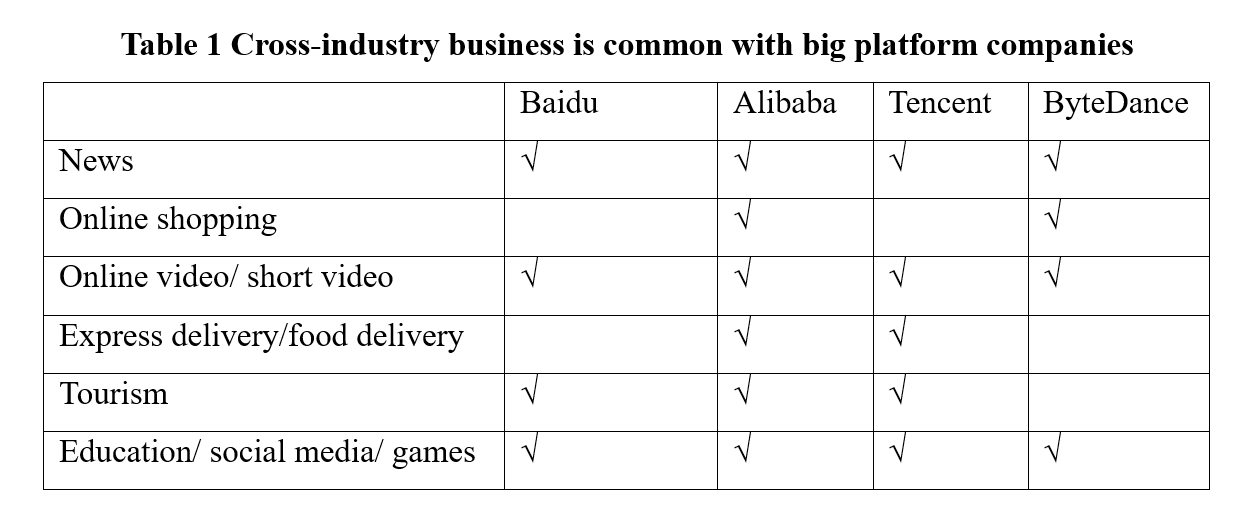

There is a distinctive difference between Chinese platform companies and American ones. In China, many platform companies do lots of cross-industry businesses. For example, Meituan is engaged in online car-hailing, Douyin in food delivery, and WeChat in e-commerce.

Economies of scope of super platforms

The above table shows that these large platforms compete in many fields, and cross-industry business has been rather common. We believe that cross-industry operations and economies of scope may allow economies of scale and full competition to coexist. In other words, even if the scale of one platform becomes rather large, it does not mean the absence of competition due to the existence of the economy of scope.

By the end of 2020, China has nearly 200 digital platforms with a market value exceeding US$1 billion. However, the combined market value of the top ten companies has dropped from 82% in 2015 to 70% in 2020. This shows that large, medium and small platforms in China are all developing rapidly, and the market of China’s platform economy is highly contestable.

However, despite the strong “contestability”, many competing platforms often receive investment from the same super investor. What does this phenomenon mean for market competition is worthy of further analysis.

VIII. SOME THOUGHTS ON FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

China’s platform economy has achieved remarkable results after more than ten years of development, which is very impressive for a developing country.

For future development, we put forward some preliminary thoughts:

1. The key to improving the governance of platform economy is to pay equal attention to regulation and development, enhance innovation vitality, maintain fair competition, protect consumer interests, and encourage sharing of platform dividend. The ultimate goal is to achieve common prosperity.

2. At present, the monopoly problem in most of the platform economies in China is not very acute. Therefore, regulation should focus on reducing anti-competitive practices, enhance contestability, and reduce the sunk cost of newcomers.

3. While laying focus on platform behavior, regulatory policies should also fully consider the characteristics of the platform economy. For practices such as "choosing one platform out of two", "big data enabled price discrimination", bundle sales, etc., it is necessary to conduct in-depth and comprehensive analysis on why these practices are legitimate or not.

4. It is recommended to establish a comprehensive governance system consists of judicial, regulatory and self-disciplinary components. Legal procedures usually are more rigorous, but they also feature large shocks, high costs and poor timeliness.

5. China must avoid campaign-style regulation, and rely more on daily and responsive regulation. It is necessary to discover problems in a timely manner, make corrections, and establish an effective appeal mechanism.

6. Regulatory policies should also keep pace with technology development and actively apply big data and other digital technologies to enhance the timeliness of regulation. At the same time, measures such as "regulatory sandbox" can be adopted to balance the relationship between business innovation and orderly development.

7. As unique business entities, digital platforms should strengthen self-discipline, be responsible giants, and take into account both economic and social goals.

This article is based on the author’s lecture at the National School of Development, Peking University, on November 18. It is the first of the livestreamed series “Twelve Lectures on Platform Economy”. The views expressed herein are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations. The article is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the author.