Abstract: In this paper, the author analyses structural problems behind the recent surge in coal prices and power rationing in some regions of China. He suggested that in the long run China consider adopting a carbon tax-based system that is supported by emission allowance trading and carbon border adjustment and supplemented by subsidies for developing and applying carbon-negative technologies; the country should realize more efficient control of carbon emissions through market mechanisms while taking into account the fair distribution of emission reduction costs.

From this September to October, surging coal prices coupled with power rationing in some regions of China has caught much attention. The authorities strongly intervened soon after, which eased the strain on the coal market for the time being. However, these power problems have exposed certain underlying structural issues that are worth thinking about and discussing.

In addition to the revision to the Safe Production Law and anti-corruption policies, other factors also need to be noted:

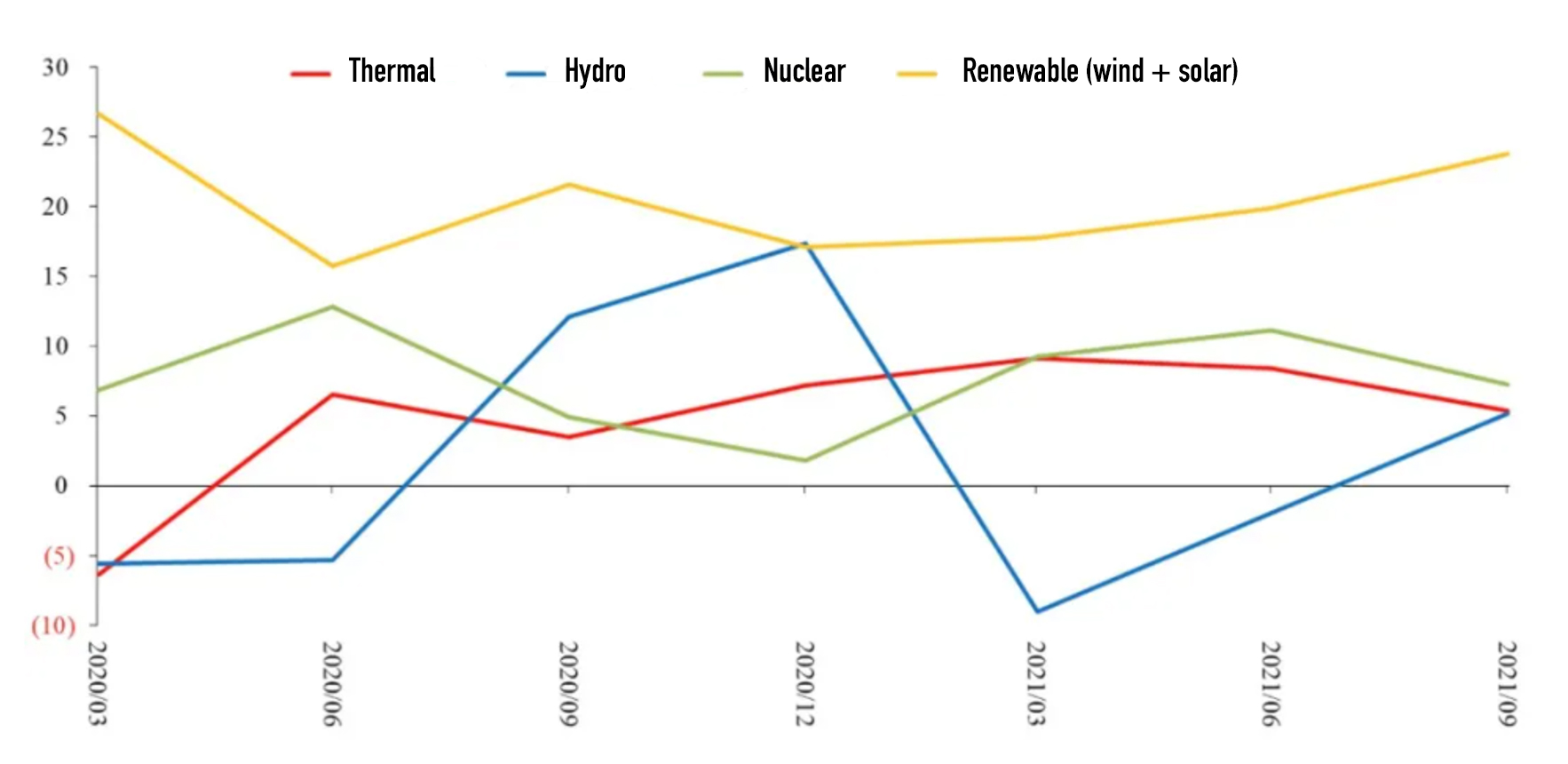

First, the shortage of hydropower caused by weather anomalies transferred the pressure of electricity supply to thermal power and then to coal. From the supply side, it is unusual that the growth rate of China’s hydropower generation this year is much lower than the average of the past six years, even lower than that of thermal power generation. This phenomenon is most likely due to extreme weather this year. Rains were concentrated in the northern region, whereas in the southern region, extremely low rainfall or short-term factors like flood storage shrank hydropower generation, forcing the increase of thermal power to fill the gap and thus pushing up the demand for coal.

Figure 1. Quarterly growth of power generation by source since 2020, %

Sources: Wind; Essence Securities

It is difficult to say if weather-induced changes in supply and demand are long-term or short-term, as we could not predict whether the weather anomalies would only occur in this year or happen on a more regular basis going forward. Yet if we assume that the weather pattern will normalize in the future, we can deem the change to be a relatively short-term shock.

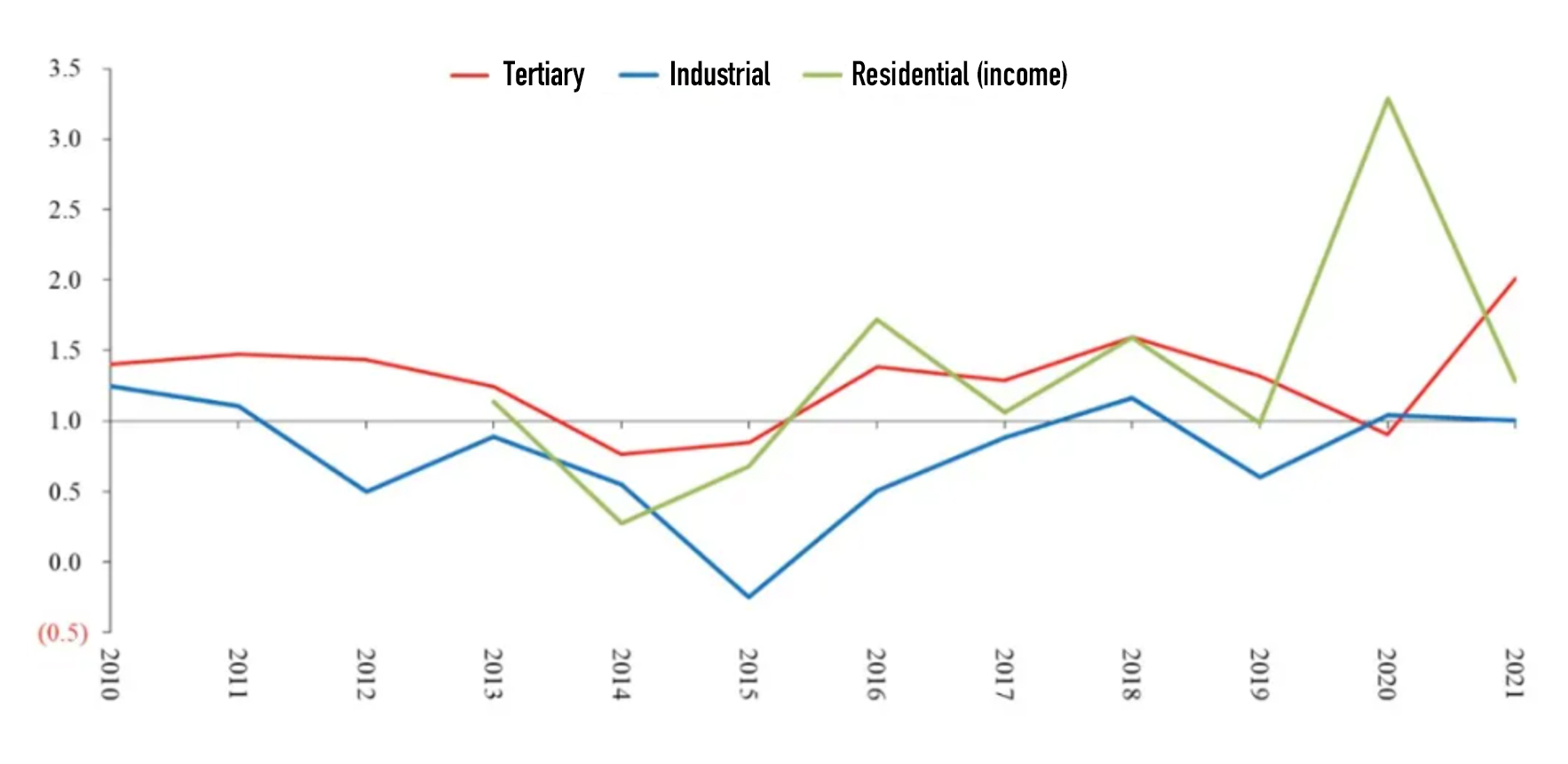

Second, China’s power demand may be experiencing some long-term structural changes, which means that thermal power generation has to be maintained at a certain growth rate for a rather long period of time ahead. From the demand side, corresponding to China’s economic slowdown over the past decade, industrial growth declined and the long-run elasticity of electricity for industrial use remained slightly below one, which led to a sharp drop in the growth of industrial electricity demand. However, this doesn’t mean that the growth rate of total electricity consumption is falling too. On the contrary, China’s total electricity consumption has been growing at a steady rate, which can be attributed to the continuous rise of power demand in the tertiary and residential sectors.

In recent years, the elasticities of electricity demand in China’s tertiary and residential sector in relation to GDP, household income and consumption have all exceeded one. Especially since 2015, elasticities have remained around 1.4. Meanwhile, as the tertiary sector increasingly accounts for a larger share of China’s economy, power demand in this sector has been pushed up by this trend and the change in structure. The same applies to residential electricity consumption.

Figure 2. The elasticity of power consumption in China’s industrial, tertiary and residential sectors between 2010 and 2021

Sources: Wind; Essence Securities

China’s industrial growth has already reached the later stage of its long-term slowdown, presently very close to the reasonable bottom level of 3-4 % in 2030, which leaves little room for further decline.

Against this backdrop, if the structural elasticity of electricity consumption remains unchanged, in the long run, the growth rate of power consumption needs to be maintained at around 5%. Under China’s current energy supply mix, the growth potential of hydropower seems to be limited. If electricity growth completely relies on alternative energy like wind and solar power, their long-term growth rate needs to remain at a high level, which seems to be unrealistic.

Therefore, for a fairly long time to come, China will have to maintain its thermal power generation at a certain growth rate, which requires sustained growth of coal consumption; meanwhile, sound measures must be adopted to save the use of electricity and energy.

Third, the inherent instability of alternative energy puts strain on the energy market. Challenges posed by alternative energy appear to be short-term problems, but in fact they have long-term implications. If we only look at national data, there seems to be no significant problem with alternative energy. But from regional data, some market participants think that problems do exist. Even if China has not felt obvious impact by these problems so far, lessons from Europe also need to be learned.

Specifically:

1. During the transition towards new energy, a surplus of production capacity of traditional energy must be ensured. As the process of “decarbonizing” energy structure continues, China’s energy supply will rely more on hydropower, solar power, wind power, etc., which are inherently unstable.

Given this situation, we must keep sufficient capacity of thermal power generation and the corresponding coal production on standby. Otherwise, disruptions to energy supply due to natural factors like weather changes will be passed onto the entire national economy through power crunch, resulting in widespread power cuts and rationing.

“Surplus” here has two implications: first, maintaining a surplus of thermal power and coal supply will increase the supply cost of thermal power relative to that of renewable power; second, given the continuous growth of power demand, if the instability of renewable power supply cannot be fundamentally changed through large-scale energy storage technology, there will be an increasing demand for a surplus in the absolute volume of thermal power and its supply capacity. In other words, to ensure a stable power supply in the future, thermal power generation and the production capacity of coal must maintain enough growth.

2. We should adopt a flexible timetable for the implementation of the dual control policy aimed at lowering energy consumption and intensity to absorb and hedge against the instability of renewable energy supply. For example, if factors like weather cause huge shortages of renewable electricity, electricity demand needs to be made up for by thermal power. If thermal power plants were forced out of commission due to the dual control policy, unstable weather will lead to widespread power rationing and instabilities in the entire economy.

Therefore, the dual control policy must be implemented on a flexible timetable, i.e., when the supply of alternative energy like hydro and wind power is sufficient, thermal power supply can be lowered to a certain degree; when the production of alternative energy dries up, we should allow thermal power to surge temporarily.

3. The dual control policy should be expanded gradually to cover more areas and guide the tertiary, residential and other sectors to reduce the use of energy and electricity.

In addition, the implications of the dual control policy on equity and efficiency also warrant discussion.

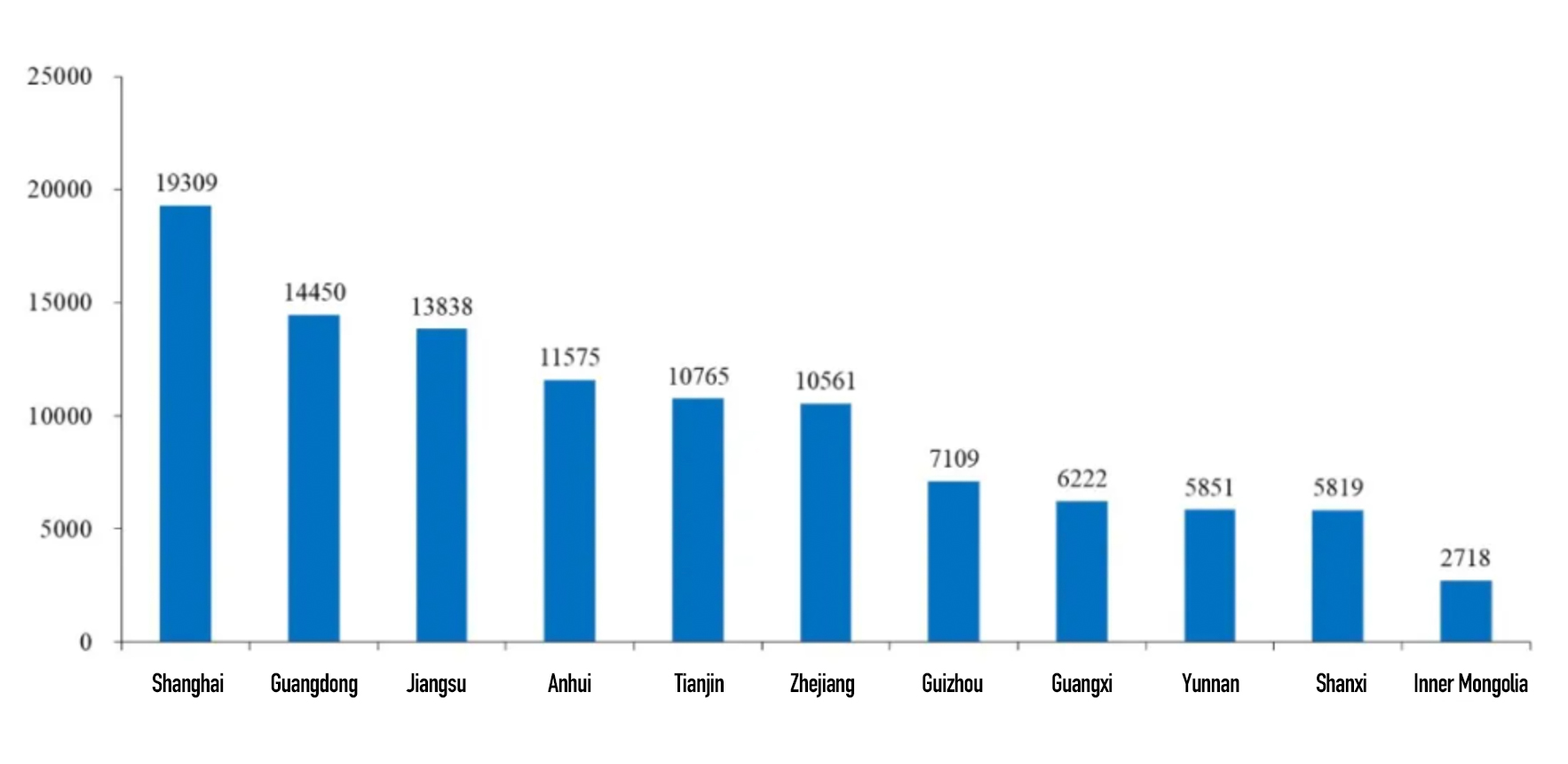

First, loss of efficiency. The figure below shows the value added per ton of carbon emissions in industrial production in some provinces of China. The numbers multiplied by 20% are roughly equal to profits per ton of carbon emissions.

Figure 3. Industrial value added per ton of carbon emissions in a number of China’s provinces, RMB/ton

Sources: Wind; Essence Securities

From these numbers, we can see that, economic output per ton of carbon emissions and the associated profits vary greatly from province to province. The gap between the most productive place (Shanghai) and the least productive place (Inner Mongolia) is seven times, while the difference between Eastern and Midwestern regions is nearly two times, which means province-specific dual control policy will cause significant loss of efficiency. In specific, if a ton of emission reduction quota for Inner Mongolia can be transferred to Jiangsu, economic output can increase by 11,000 RMB. The same logic applies to other provinces.

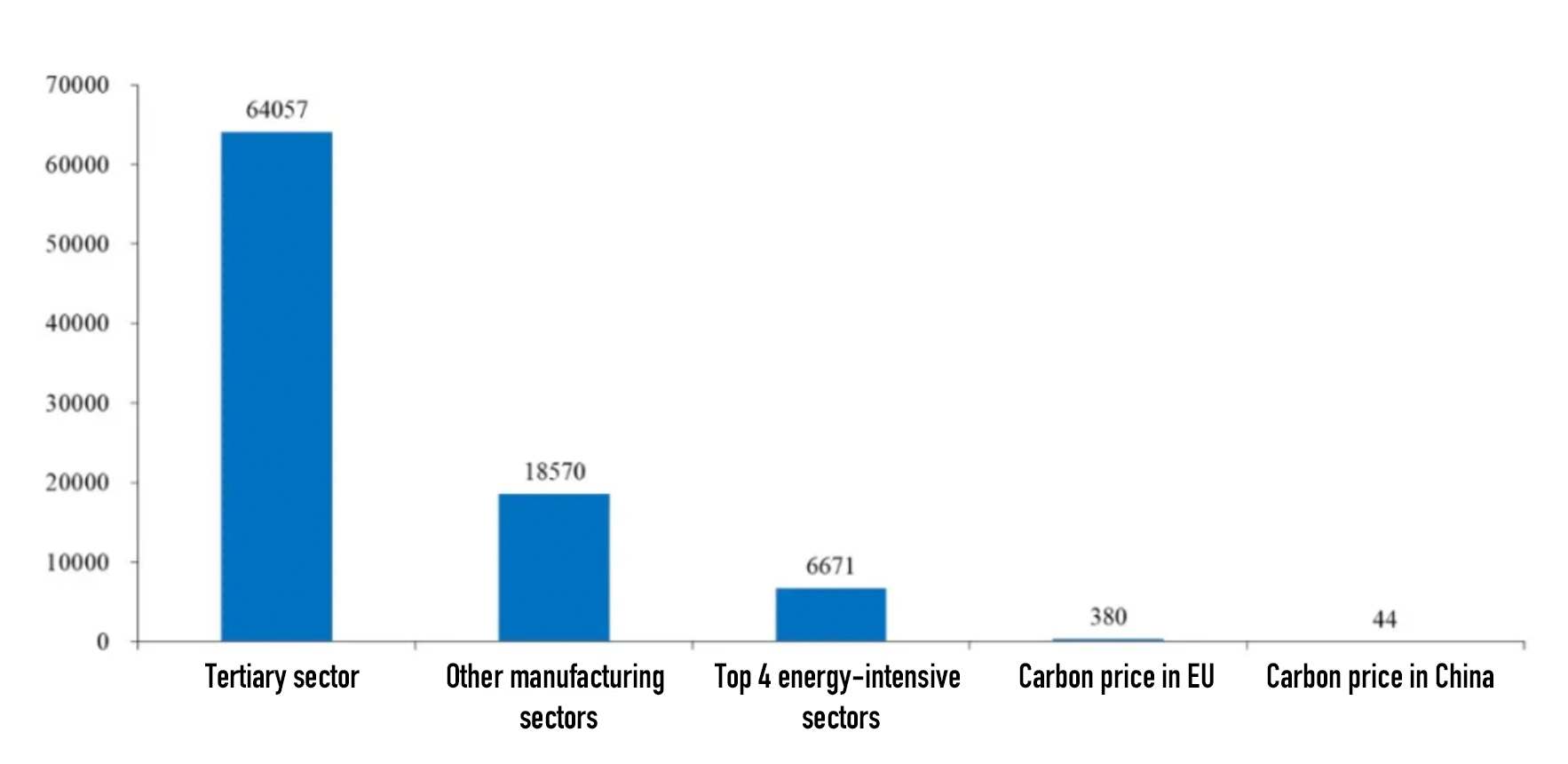

In China’s top four energy-intensive sectors, the value added per ton of carbon emissions is around 6,671 RMB; the figure is 18,570 RMB in other manufacturing industries and 64,057 RMB in the tertiary sector. Among them, the tertiary sector features quite different technicalities of electricity demand, whereas energy-intensive industries and other manufacturing industries are powered predominantly by electricity, making them heavily reliant on this energy.

Take the top four energy-intensive industries that generate the lowest value added per ton of carbon emissions as an example, their economic output per ton of emissions is about 6,671 RMB. Based on the 20% profit margin mentioned above, their profits are between 1,200 and 1,300 RMB, corresponding to an implied price of carbon emissions per ton at 1,200 to 1,300 RMB. Among global markets, the EU emission trading market is rather established. This year, its carbon price has been rising due to the increasing pressure on emission reduction. However, recent carbon price in the European market is merely 380 RMB per ton, far lower than the implied price in China’s energy-intensive sectors.

Figure 4. Value added per ton of carbon emissions in energy-intensive and other manufacturing sectors, RMB/ ton

Sources: Wind; Essence Securities

There are two possible explanations.

One explanation is that if we assume the price of carbon credits decided by European carbon market is effective, this means China can choose to purchase carbon credits from Europe at 380 RMB per credit for its energy-intensive industries. In this way, over 800 RMB of profits can be gained. In other words, China’s current dual control policy also causes efficiency loss internationally.

The other explanation is that if we assume the European carbon market to be not that mature, its price signals therefore could not provide a good reference. This means that China’s industrial sector will have to pay for carbon credits at a price of over a thousand RMB per ton, placing considerable pressure on the economy to adjust itself.

Specifically, if we rely solely on the price signals of carbon trading to achieve emission reduction, the pressure of reducing emissions would be concentrated mainly or entirely on a few carbon-intensive industries such as steel and cement. This practice might be efficient economically, but it will hit economic activities hard. It also raises the issue of fairness.

Moreover, the government currently reduces emissions through curbing production of energy-intensive sectors, resulting in soaring prices and thus excess profits in these industries. Take the first half of this year as an example, output restrictions have partially contributed to rising PPI. Curbing output has pushed up prices and allowed energy-intensive sectors to gain huge profits. But the government cannot directly or fully share in the benefits related to carbon emission control, which reduces it fiscal capacity to subsidize low-carbon industries and low-carbon transition. This is something to think about in terms of fairness.

Taken together, from the recent fluctuations in the coal market, we have the following takeaways:

First, while transitioning towards new energy, enough surplus of conventional energy capacity needs to be ensured before the wide application of large-scale and low-cost energy storage technologies.

Second, the dual control policy should be implemented on a flexible timetable so as to hedge against the potential volatility of renewable energy supply.

Third, the dual control policy should gradually cover more sectors and have its technology design optimized.

In the long run, China should probably consider adopting a carbon tax-based system that is supported by emission allowance trading and carbon border adjustment and supplemented by subsidies for developing and applying carbon-negative technologies; it should realize a more efficient control of carbon emissions through market mechanism while taking into account fair distribution of emission reduction costs.

This article first appeared on CF40’s WeChat blog in Chinese on November 18. The views expressed herein are the author’s own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations. It is translated by CF40 and has not been reviewed by the author.