Abstract: In this article, the authors explored the mystery of sluggish infrastructure investment in China.They pointed out that local governments and their financing platforms are the main force in infrastructure-related investment, and the decline of investment in municipal projects has been the biggest drag. They predicted that the annual growth of China's infrastructure investment would be about 4% in 2021, which will continue the downward trend since 2018.

I. CALCULATION OF INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT

Infrastructure investment is reflected by fixed asset investment in relevant industries. Two methods can be applied to calculate infrastructure investment. One thing to note is that data on the absolute scale of infrastructure investment has become unavailable since the end of 2017.

One method is to calculate infrastructure investment using sectoral data. Infrastructure construction includes three major industries: (1) Production and supply of electricity, heating power, gas and water; (2) Transportation, warehousing and postal service; (3) Water conservancy, environment and public facilities management. We can calculate the scale of fixed asset investment in various industries based on the monthly growth rate by industry and the absolute scale of infrastructure investment in 2017 announced by the National Bureau of Statistics. Summarizing the data of various industries, we can get the growth rate and scale of infrastructure investment.

The second method is to refer to the calculation by the National Bureau of Statistics. Compared to the first method, industries covered under this method do not include the production and supply of electricity, heating power, gas and water, and the sub-category of warehousing. In the meantime, it adds sub-categories of telecommunication, radio, TV, satellite transmission, Internet and related service industry.

Due to the need to calculate the contribution of each sector and to ensure the historical comparability of the year-on-year growth rate of infrastructure investment, this article does not use the calculation by the Bureau of Statistics but adopts the first method which is more commonly used by market analysts and has proved to be rather reliable. As shown in Figure 1, after getting the investment scale of each separate industry by this method, we then gathered the data and figured out the cumulative year-on-year growth rate of infrastructure investment, using industry classification adopted by the National Bureau of Statistics. We found that the results of our calculation of infrastructure construction growth are broadly in line with data released by the National Bureau of Statistics.

II. TWO STYLIZED FACTS ABOUT INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT AND THE IMPLICATIONS

Stylized Fact 1: Funds on the fiscal budget have little impact on infrastructure investment, and more than 80% of infrastructure funds come from beyond the budget.

The sources of fixed asset investment fall into five categories: budgetary funds, domestic loans, self-raised funds, foreign capital, and other funds. Among them, budgetary funds can be construed as funds directly allocated by governments' fiscal budgets. According to the latest data, it can be found that the proportion of budgetary funds used in infrastructure investment is not high. As shown in Figure 2, only 17.5% of infrastructure investment in 2019 came from budgetary funds. The production and supply of electricity, gas, and water use the lowest proportion of budgetary funds at a level of 8.0%. The proportion of budgetary funds in investment in water conservancy and public facilities management is at the highest level of 21.2%. At the same time, both overall infrastructure construction and the separate industries have shown a downward trend in investment (Figure 2).

The budgetary funds mainly come from three parts, general public budget, special debts, and land transfer revenue. Based on the data of 2019, we conducted a simple estimate of the proportion of various budgetary funds for infrastructure investment. In 2019, funds from the general public budget, special debts, and land transfer revenues that were used for infrastructure investment were 2.27 trillion yuan, 282.3 billion yuan and 681.6 billion yuan respectively, totaling 3.23 trillion yuan, equivalent to 17.8% of the total infrastructure investment. The results are broadly consistent with the 17.5% of budgetary funds in infrastructure investment mentioned above.

In terms of the general public budget, government expenditure that is publicly disclosed is classified into three levels. On the top level, expenditures related to infrastructure include 1)energy conservation and environmental protection, 2)urban and rural communities, 3)agriculture, forestry and water, and 4)transportation. However, part of these expenditures will also be used for administrative management or subsidies. So the funds that go into infrastructure projects should be observed at lower levels. According to data on the execution of the central and local budgets for 2019, within the general public budget, actual expenditure on infrastructure development is about 2.3 trillion yuan.

Next, there is special debt. The year 2019 witnessed an increase of special debts of 2.15 trillion yuan, most of which were invested in shantytown renovation and land reservation. The investment in infrastructure is shown in Figure 3, totaling 282.3 billion yuan.

In terms of the land transfer revenue, only about 9% of the funds directly invest in infrastructure. Since national data related to land transfer revenue are not available, here is an estimate based on the situation in Hunan Province in 2019. In 2019, expenditure from land transfer revenue in Hunan was 192.67 billion yuan, most of which was used for land acquisition, demolition compensation and land development. Infrastructure-related expenditures included urban construction and rural infrastructure construction, totaling 176.6 million yuan, accounting for only 9.2% of total land transfer revenue. Assuming the 9.2% also applies to the national situation, the national land transfer revenue used for infrastructure investment would be 681.6 billion yuan.

In other words, more than 80% of the funds for infrastructure development are extra-budgetary. Among them, the proportion of funds led by local government financing platforms (LGFPs) is estimated to exceed 60%. In 2019, private fixed asset investment in infrastructure accounted for 23% of the total investment. Then it can be considered that the remaining 77% comes from the government and state-owned enterprises. After excluding the proportion of foreign capital in the budget, we can calculate the proportion of money from LGFPs in infrastructure investment (Table 2).

Stylized fact 2: Public facilities construction and management, as well as related investment, are the largest component of infrastructure investment, and they are the main factor that has dragged down the growth of infrastructure investment in recent years.

Among the three major industries that make up infrastructure, one prominent change in recent years is that water conservancy and public facility management have gradually become the dominant part of infrastructure construction. Investment in these activities from January to July 2021 accounts for 46.2% of total infrastructure investment, significantly higher than the other two industries (Figure 4).

However, the growth of water conservancy and public facilities management has declined significantly since 2018, from 21.2% in 2017 to 0.2% in 2020, seriously slowing down the growth of total infrastructure investment. Its contribution to the overall infrastructure growth in 2020 was only 2.8% (Figure 5).

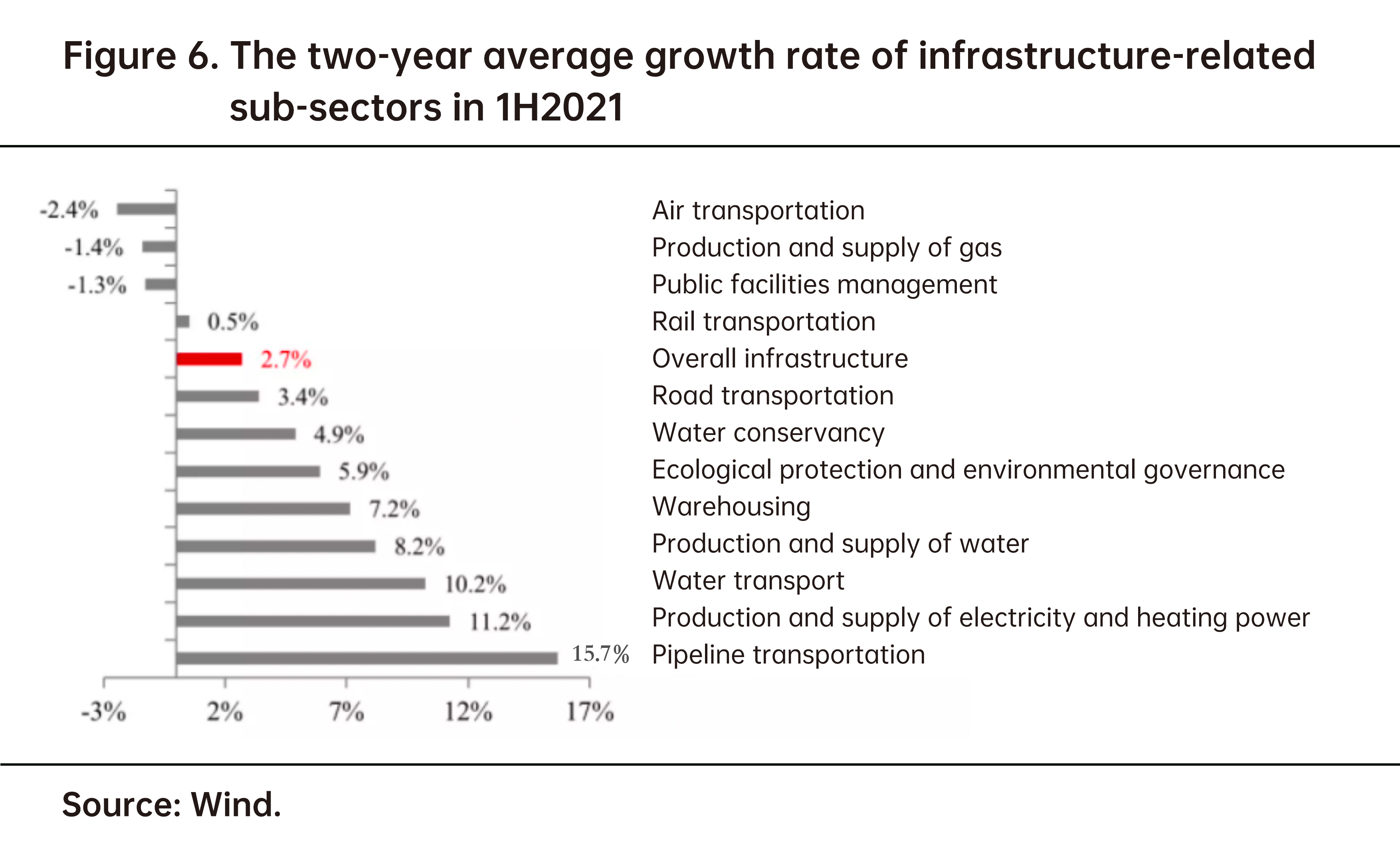

Judging from the data from January to July 2021, infrastructure investment was generally weak, and the year-on-year growth in July fell to -10.1%. However, from the perspective of the growth of infrastructure-related sub-sectors, the biggest negative factor is an investment in public facilities construction and management. When further dividing the sectors of infrastructure, as shown in Figure 6, we can see from the two-year average growth rate from January to July 2021 that investment growth of eight industries such as pipeline transportation (15.7%), electricity and heat production (11.2%) and water transportation (10.2%) is higher than overall infrastructure growth.

The three sectors of air transport (-2.4%), gas production and supply (-1.4%), and public facility management (-1.3%) showed negative growth on average over the two years. The negative growth of air transport is mainly caused by the regulation and shrinkage of the aviation industry brought about by the covid-19 pandemic. As the proportion of gas production and supply in total infrastructure construction is small (only 1.4% in January-July 2021, authors’ calculation), its decline has little impact on overall infrastructure investment growth. What is worthy of attention is the change in public facilities management. According to our calculation, the scale of investment in public facilities management from January to July 2021 is 3.6 trillion yuan, the highest among all sub-sectors, accounting for 36.2% of total infrastructure investment (Table 3). Its negative growth has reduced the two-year average growth of total infrastructure investment by 0.5%. Road transportation, and production and supply of electricity and heating power, which ranked second and third in infrastructure investment, contributed to the overall growth of infrastructure investment by 1.14 and 1.51 percentage points, respectively.

Public facilities management mainly includes the management of municipal facilities, tourist attractions, the appearance of towns and cities, parks, greening and environmental sanitation. According to the latest data, as shown in Table 4, the largest investment went to the management of municipal facilities (66.3%), followed by the management of tourist attractions (17.2%). The two account for more than 80% of total investment in public facilities management. To sum up, the slowdown of investment in public facilities management of which municipal construction was the dominant part is the biggest drag on overall infrastructure investment.

Urban construction is mostly funded by LGFPs. According to the calculation in Table 2, more than 60% of the funds invested in public facilities management which is dominated by municipal projects come from state-owned enterprises. Combining the above two basic facts, we can draw a basic conclusion: in the past ten years, local governments and their financing platforms have been the main force in infrastructure investment, and the platforms’ investment in municipal projects has declined in recent years, severely dragging down infrastructure investment.

III. BEHIND THE SLOWDOWN IN MUNICIPAL INVESTMENT IS INCREASING RISK AVERSION

As analyzed above, budgetary funds account for a small portion of total infrastructure investment. The slowdown in infrastructure investment since 2018 is mainly caused by the sluggish growth of municipal investments which are mostly led by LGFPs who are major investors in infrastructure projects. These platforms have supported these projects with off-budget funds.

At present, fiscal situation and policy are important factors shaping the behavior of LGFPs. China’s fiscal policy was once oriented toward promoting growth. However, since 2018, the government has reiterated the importance of preventing and resolving risks associated with the implicit debts of local governments and risk prevention has become the paramount goal. This, on the one hand, has significantly reduced the proportion of infrastructure expenditure in the budget; on the other hand, with declining fiscal income and mounting debt risk, issuance of new local government bonds has been delayed, and resolving risks associated with the implicit debts has become ever more urgent.

A key element of resolving fiscal risks is to cope with the pressure of fiscal revenue decline and safeguard the bottom line of three guarantees (on basic livelihood, wages, and government running). Governments, central and local, have been under strain on the revenue end since the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, and reducing expenditure has become a widely embraced solution to cope with the pressure. Back in 2019, because of the downward pressure on the economy and massive tax and fee cuts, China recorded a growth of 3.8% in general public budget revenue in 2019, the lowest since 1987, and growth in tax revenue of as low as 1%. Had there not been the pandemic, policymakers may have already taken action to stabilize the macro tax level and exit from the tax and fee cuts. However, the sudden outbreak of the pandemic disrupted the process. In 2020, general public budget revenue slid by 3.9%, and tax revenue by 2.3%. The proactive policy stance at the revenue end only reflects the bottom-line mentality of Chinese policymakers at unusual times.

At the two sessions this year, the Ministry of Finance reflected on the fiscal situation in 2020 and said that “the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic led to a sharp fall in national fiscal revenues and a prominent imbalance between revenues and expenditures, and local fiscal operations, in particular, were confronted with difficulties." (Report on the Implementation of Fiscal Policy of China for 2020). Looking ahead at the year 2021, it is expected that the fiscal situation would be very tough with increasing difficulties in achieving a balanced budget.

Words such as “prominent” and “very” were rarely seen in such documents in previous years. This reflects the fiscal authority's basic judgment of the fiscal situation. As a result, on the expenditure end, there has been a marked decrease in the proportion of infrastructure expenditure in the general public budget as well as its growth since 2019 (Figure 7).

In the first half of 2021, the two-year average growth in expenditure on infrastructure-related sectors was in the negative territory (Figure 8). Specifically, expenditure on urban and rural community development experienced the sharpest decline, by 17.3%. Many expenditures on community development and public facilities management overlap. Although budget funds account for only a small portion of total infrastructure investment, the slide in fiscal expenditure on infrastructure could directly explain the sluggish growth in investments in public facilities management.

With declining fiscal income and mounting debt risk, issuance of new local government bonds has been delayed, and it has become ever more urgent to resolve the implicit debts. In 2021, the issuance of local government bonds has been slow. Statistics show that in the first 7 months of the year, Inner Mongolia, Hainan, Qinghai and Ningxia did not issue new special bond at all, but according to public data, the first three provinces have been allocated quotas of 64.3 billion yuan, 55.3 billion yuan and 7.9 billion yuan, respectively. They have left the quota unused because their high debt ratios in 2019 were high (calculated as balance of explicit debt / (general public budget revenue + government fund budget revenue + transfer payment)). Inner Mongolia's debt ratio was 137%, Hainan, 102%, and Qinghai, 114%. Data for Ningxia is not available. Local governments are already facing mounting pressure from explicit debts, and with fiscal revenue declining, implicit debts are adding to the risks.

Resolving these debt risks is a complicated task. Local governments now seem to prefer to distinguish between old and new debts and resolve the implicit debt issue first. Therefore, the slowdown in municipal and infrastructure investments is a result of decreased willingness to invest among LGFVs caused by the pressure of fiscal revenue decline and debt risks. Naturally, non-essential expenditures like those on municipal projects and tourist spot development would be cut first when the government reduces overall expenditure. Outside the budget, a large number of municipal projects were undertaken by the LGFVs. But this year, with the increasing focus on resolving implicit debt risks, financing channels of LGFVs have been restricted. As a result, public facilities management especially municipal projects and tourist sites have become the biggest drag on infrastructure investment.

IV. THERE WILL BE NO SIGNIFICANT BOOST OF EXPENDITURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE YEAR, AND RISK-CONTROL IN LGFPS WILL CONTINUE TO SUPPRESS INFRASTRUCTURE GROWTH.

Some predict that the fiscal space achieved through revenue growth outpacing spending in 1H2021 and the expected increased issuance of local government bonds in 2H2021 will give more play to fiscal spending and therefore boost infrastructure investment. However, China's fiscal system determines that spending will not be largely expanded, and the risk control over local financing platforms will continue to stifle infrastructure growth. The yoy infrastructure growth rate is expected to be 4.1% in 2021.

First, although fiscal revenue grew faster than spending in 1H2021, it leaves minor space for big over-budget spending plans. In 1H2021, the two-year compound growth of general public budget revenue (4.2%) is 5 percentage points higher than spending (-0.8%) and is greater than the same period in 2019 (3.4%). The quick growth of fiscal revenue was mainly due to the withdrawal of tax cuts and an increase in tax income from higher commodity prices. It frees up fiscal space, but the boost in tax revenue from price increases is only temporary, and fiscal departments at all levels will continue to be concerned about potential revenue declines.

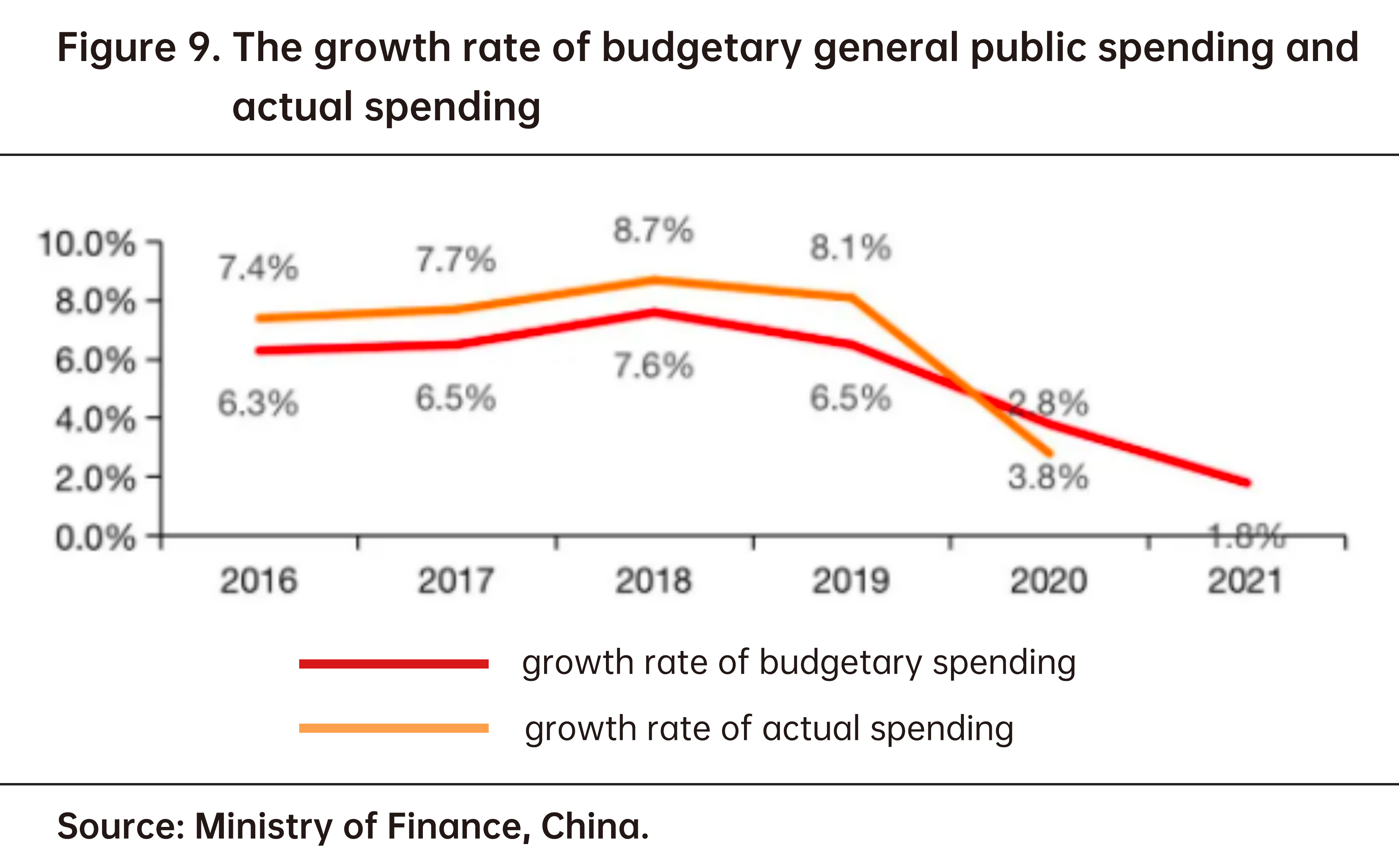

Based on the data of previous years, the gap between the growth rate of budget execution spending and the planned growth rate would not be very big (Figure 9), with only a 1 percentage point variation range. This is due to the nature of the budget system, in which each level of government has its budget created with some regularity in the previous year, and any adjustments must follow the procedures outlined in the Budget Law. This is especially true for infrastructure budgets, which are tied to government investment plans and subject to a variety of budget evaluation systems. Furthermore, given the pressure of “three guarantees” (on basic livelihood, wages, and government running) on local governments, the increased revenue would mostly be applied in the three areas, and infrastructure investment will not increase significantly.

Second, the accelerated issuance of local government bonds in 1H2021 will take time to complete and is not much related to the past record with infrastructure investment. The issuance of local government bonds has slowed since 1H2021, owing to inefficiency in the early use of funds. Given the gravity of the budget arrangements, this year’s quota is expected to be used up by the end of the year, although this may not help spur infrastructure investment growth for three reasons:

(1) The existing local bonds management system reflects inefficiencies in the utilization of local government bonds and special bonds, which stems from a lack of projects that could meet the government's investment requirements. According to the local bonds system, when determining the bonds limit for each local government, "the provincial finance department puts forward proposals for new issuance of special bonds and public welfare projects for the following year." In this link, the local governments do not evaluate the projects to be undertaken but rather report a roughly estimated amount of special bonds to be issued. Later when they obtain the funds from issuance, they might run into many obstacles to project implementation such as feasibility assessment, environmental protection, land use and planning. Suspension of projects may also result in mismatched funds and projects, such as the situation where “money waits for the projects.” One of the reasons for the delays is the growing scarcity of projects that meet government investment requirements. General bonds issued by local governments can be used for capital expenditures and do not have to earn much yield. Special bonds, on the other hand, are obliged to be invested in public-interest projects with a certain level of return. Debt and interest payments on these projects should be made out of revenue from government funds or special bonds, and the operation is under more stringent performance control. At the local level, such projects are scarce.

(2) Local government special bonds have increased in recent years, but infrastructure investment has fallen, i.e the two are not positively correlated. After the local governments were given the authority to issue bonds in 2014, only 100 billion yuan special bonds were issued in 2015. Then they were boosted by 800 billion in 2017, 1.35 trillion in 2018, and even 3.75 trillion in 2020. At the same time, infrastructure investment growth slowed from double digits to single digits, with several months showing a negative growth rate. In 2021, no new local government bonds were issued in January or February, followed by 264 trillion in March and acceleration from March to June (Figure 10), but infrastructure investment growth turned negative, hitting -10.1% in July. It makes it even harder to believe that the faster bond issuance in the second half of the year will immediately bring infrastructure investment back to life.

(3) Risk control efforts by LGFPs will continue to stifle infrastructure spending. As we estimated earlier, local financing platforms organize the majority of investment in the public facilities management industry, as well as infrastructure investment. The current tight control of local government financing platforms may make it difficult to boost infrastructure before local hidden debts are more or less resolved. We estimate that the scale of budgetary funds to support infrastructure will be 3.8 trillion yuan in 2021 (Tab. 5), based on the increasing proportion of budgetary funds: the original domestic loans and self-financing funds will be replaced by special bonds as a result of the crackdown on illegal local financing; the scope of business conducted using self-financing funds and debt funds have shrunk as a result of the tighter regulation of financing platforms. Based on the size and proportion of budgetary funds, we estimate that the growth rate of infrastructure will be 4.1% in 2021, which is quite low and continues the sluggish infrastructure investment trend that began in 2018.

The article first appeared in Chinese on CF40's WeChat blog on August 20, 2021. The views expressed herewith are the authors' own and do not represent those of CF40 or other organizations. The English version has not been reviewed by the author.