Abstract: Rebooting and restructuring are both part of the post-pandemic economic recovery process. The general changes include the reduced asset bubble risks and financial risks, narrowing wealth gap, and rising inflation pressure. In different countries, the transitional economy presents itself in differently ways. Significant increase in mean inflation rate in the US is likely to be fueled by once-in-a-generation supply shocks as well as the unprecedented exogenous money supply, which could pose the biggest risk to the global economy and financial markets. For China, its top priority is to address the debt issue: orderly restructuring keeps credit spreads in check, whereas disorderly clearing might lead to credit spread overshoot. Because the restructuring is in general oriented towards tight credit, loose monetary policy and expansionary fiscal policy, it’s important to keep track of China’s CBDC development and financial concessions.

There have been two major concerns in the market recently.

One is the dramatic rise in inflation in the United States. CPI inflation in the US climbed to 5.4% in June, but the 10-year Treasury yield fell. Does that mean inflation is not a problem or the market misjudged?

The other concern is the high PPI and rising production costs in China. When the market was speculating on how much PPI would affect CPI, the People’s Bank of China surprised the market by lowering the reserve requirement, igniting debate over China’s economic prospects and monetary policy.

Both concerns are tied to how we perceive current and future economic trends, which I summarize as “a great change from reboot to restructuring.”

When the pandemic is under control, there is a resumption of economic activities as well as a shift in economic structure. As the Queen of the United Kingdom famously asked, with so many economists in the world, why couldn’t anyone predict the severe financial crisis in 2008? Of course, no medical expert could have predicted a catastrophic pandemic like the COVID-19, but if we look back in a few years, will we ask ourselves, have we misjudged the economic impact of the pandemic? If so, what are the mistakes we have made?

To answer these questions, this article illustrates the recovery and the restructuring of economic activities after the pandemic is brought under control and its implications for the economy, the market, and policymaking, taking into consideration factors such as the economic fallout of the pandemic, mid- to long-term structural changes, as well as the 14th Five-Year Plan and policy orientations.

I summarized the implications into three points.

First, the US should focus on mid-term inflation. I started to warn about the risk of inflation in the second half of last year when most people in the market didn’t believe it. Now the risk has materialized, but the market is split on whether the current inflation surge is transitory or to stay. Most believe the inflation will be temporary, but I disagree. I think inflationary pressure will persist into the medium run. That’s to say, the short-term shock may turn into the rise of mid-term mean inflation.

Assuming that the mean inflation has climbed from 1.5% to 3% over the last two decades, we could see an inflation rate of 5% to 6% in the US at the high point of the future economic cycle. What will such an inflationary environment mean for the US and the global economy, especially with the US dollar as the international reserve currency?

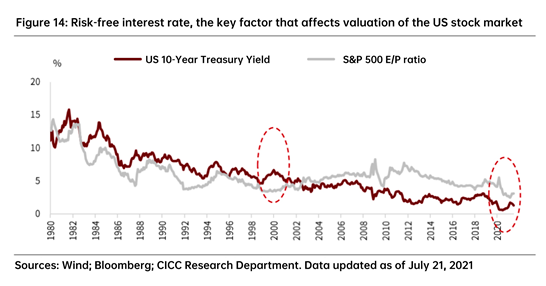

It means the recent drop in the yield on the 10-year US Treasury bond is temporary. However, due to the US dollar’s unique status, its upward potential may be constrained by worldwide demand for safe assets. When the economic weather is bad, people seek out safe assets, resulting in a drop in yield.

The value of the US stock market, if measured conventionally, is currently at a high level, yet it’s not so high when considering that the country’s interest rates are extremely low. Risk-free interest rates are crucial to the US stock market's trajectory, which is why the biggest risk is an upward change in the mean inflation. According to the logic of mid-term inflation, global stock markets will become more volatile, with EM stock markets being struck harder.

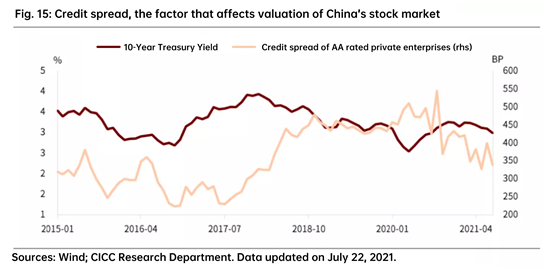

Second, China's biggest challenge in the coming years will be debt rather than inflation. There are two solutions: orderly debt restructuring and disorderly market clearing. Both will cause risk-free interest rates to fall, resulting in interest rate divergence between the US and China. How much of a constraint will this place on China's monetary policy? China, as a huge economy, must formulate monetary policy tailored to its own realities, but the question is how to insulate Chinese policy against spillovers from US monetary conditions?

This might mean more flexibility in the RMB exchange rate, as well as the use of macroprudential regulation if needed. In addition, fiscal expansion can help ease the pressure on the authorities to loose monetary policy.

In China, lower risk-free interest rates will push up the valuation of the stock market, however, credit spread matters more. The rise in credit spread is limited in the case of orderly restructuring; but in the case of disorderly clearance, risk exposure could drive up credit spread, resulting in higher risk premiums and stock market turmoil.

Third, the macro trend is restructured towards "tight credit, loose monetary policy, and expansionary fiscal policy".

As a result of the market credit cycle and macro-prudential regulation, particularly in the real estate sector, China's debt burden tightens up banks' capital support to the real economy. Control on real estate, which is often used as collaterals, serves to restrict credits.

Amid a tight credit environment, economic growth requires "loose monetary policy and expansionary fiscal policy". The term "loose monetary policy" refers to the central bank's efforts to lower the price of base currency (risk-free interest rate) or quasi-fiscal operations such as central bank re-lending. China's quasi-fiscal operations may further extend to the banking system in the form of interest concessions by financial institutions, and China's budget may not be expanded as substantially as the US's.

I. COVID-19 MAY DISTURB THE RECOVERY TEMPO BUT WON’T STOP IT.

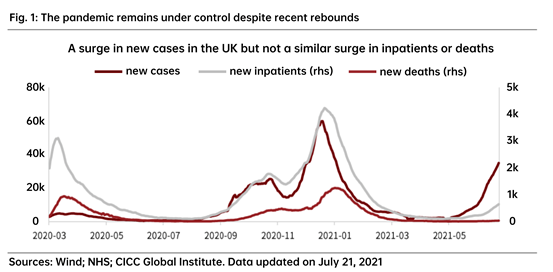

First of all, it’s necessary to follow the update of the pandemic, as it continues to pose a significant threat to the global economy. Despite the recent twists and turns and resulting worries, I generally believe the pandemic situations are still under control in major economies.

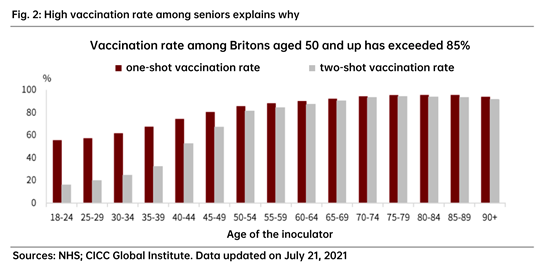

For example, despite the dramatic increase in new cases in the UK recently, new inpatients and mortality are at low levels, which is different from previous rebounds. With only a small share of confirmed cases turning critical or fatal, the economic shocks are not as severe as last year. High vaccination coverage among the elderly explains this phenomenon. In the UK, more than 90% of the population over 60 have been vaccinated. With the elderly well protected, even if the young are infected, the proportion of severe cases and deaths should be low.

It’s safe to say that the recurrence of the pandemic is unlikely to have a significant impact on the economy, but still it’ll be difficult to return to normal in a short period of time. We need to review what has happened to the global economy in the last year or so, and in particular, what has changed the macroeconomic landscape.

II. A ONCE-IN-A-GENERATION SUPPLY SHOCK

Inflation is triggered by either insufficient supply or excessive demand. The supply shift induced by the pandemic, in my opinion, is a once-in-a-generation shock.

Supply shock occurs frequently, like the recent flood in Henan province and past earthquakes in other parts of China, but what we’re witnessing now is a global shock with huge impact. The last time a global supply shock of this magnitude happened was during the oil crisis in the 1970s.

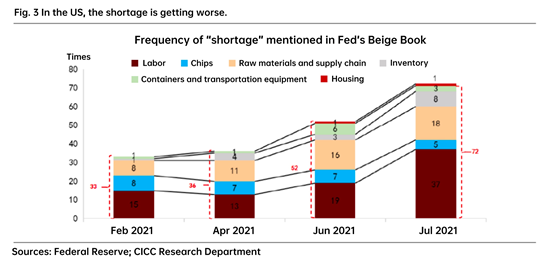

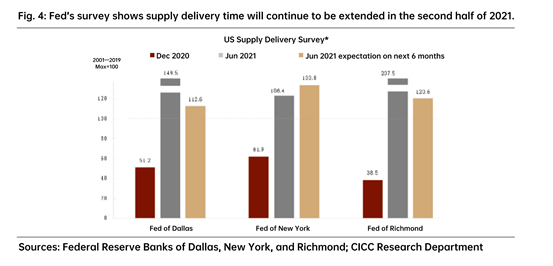

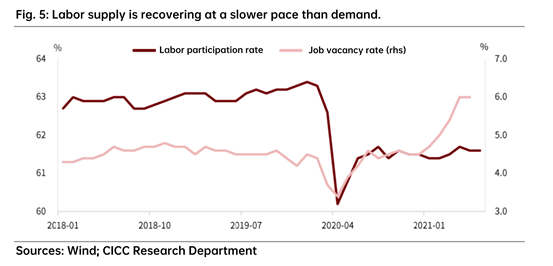

Another example is the frequent appearance of the term “shortage” in Fed’s Beige Book, notably in relation to the “l(fā)abor market”. According to the Fed’s survey, supply delivery will remain inefficient in the second half of 2021, with the recovery of labor supply lagging behind demand. It’s hard to be oblivious of the widening gap between labor supply and demand when looking at the job vacancy rate and labor force participation rate. The job vacancy rate represents the share of jobs not filled and shows labor demand; labor force participation rate measures how many individuals are willing to find a job and therefore reflects labor supply.

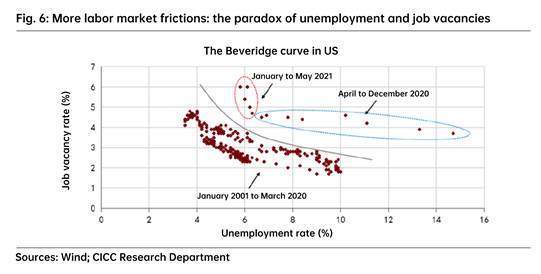

People's willingness to work has been eroded by government subsidies, women's need to care for children, and, more seriously, people's apprehension against collective activities. In a normal labor supply-demand relationship, the unemployment rate rises in tandem with the drop in job openings; but, as a result of work and production suspension during the pandemic, the unemployment rate soared while vacancies did not go up.

However, it's worth noting that the US labor market has witnessed a significant increase in job openings while maintaining a nearly consistent unemployment rate, which is known as the mismatch in the US labor market.

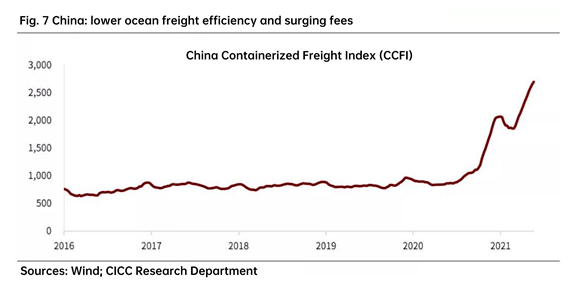

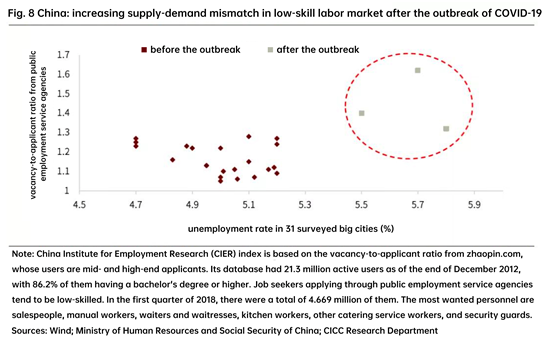

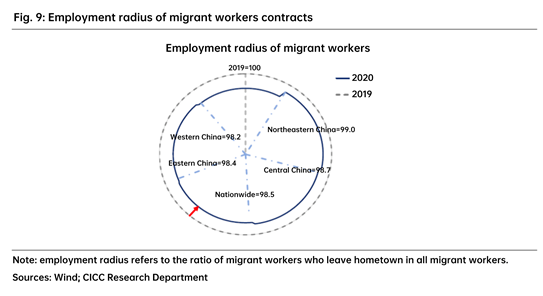

In China, the situation is similar. In terms of supply, the cost of ocean freight has been growing. As evidenced by rising unemployment rates and rising vacancy-to-applicant ratio from public employment service agencies in 31 surveyed big cities, the pandemic has exacerbated the mismatch of labor supply and demand in low-income groups. The mismatch is also reflected in the contraction of the employment radius of migrant workers, indicating that they are less eager to leave their hometown.

The previous examples might be temporary phenomena and would cease to be issues when the pandemic subsides and the economy gets back on track. The decline in supply elasticity, however, is not a short-term problem, because in addition to short-term impacts of the pandemic on people’s behavior, mentality and activity radius, some medium- and long-term factors are at play as well.

First, anti-globalization. The shock of COVID-19 compounded by geopolitical conflicts and technological competition among major powers has given rise to anti-globalization, one of the signs being a shift of focus from efficiency of supply chains to security. Economically, such a shift means an increase of cost. In a globalized era, advanced technology can rapidly flow into emerging markets, which helps improve efficiency of the global industrial chain and thus benefits all countries. If international frictions slow down technological advancement, global cost could rise.

Second, green transition and carbon neutrality. For a considerable time into the future, they will drive up cost and put a drag on economic activities, causing stagflationary pressure on the world economy. In the long run, green transition is a good thing. But in the short run, it will bring shocks to the economy, otherwise, every country will be willing to push forward carbon neutrality without the need for international coordination.

Third, labor relations. Recent moves such as Biden’s pro-union push, G20 agreement on a global minimum corporate tax, and better social security benefits for gig workers of platform companies, are all helpful in increasing the income of ordinary people, but they could also push up labor cost.

In addition to the factors mentioned above, population aging in major economies poses another supply-side constraint. Together, they add up to “a once-in-a-generation supply shock”, causing not just short-term issues, but also a decline in supply elasticity in the medium and long term.

III. DEMAND: INJECTION OF EXOGENOUS MONEY UNSEEN IN DECADES

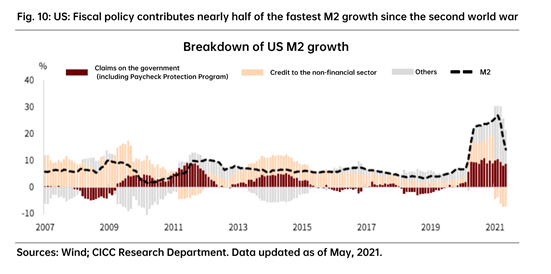

After the COVID-19 outbreak, the growth of US money supply has hit a record high since the Second World War. This is not a normal growth, but rather a growth of exogenous money. What is exogenous money? In the words of Milton Friedman, exogenous money is money dropped from a helicopter or the sky, which can boost consumption. Historically, the most important example of exogenous money is gold. Supply of gold depends on what can be mined instead of economic operation.

In modern society, exogenous money is injected through fiscal policy, which reflects the policy orientation of the government rather economic fluctuations in the private sector. Injecting money through fiscal policy takes two basic forms: first, free transfer payment; second, purchase of labor and services from the private sector, such as government procurement and salary paid by the government to civil servants, which all mean increase of net asset and revenue in the private sector and thus will significantly stimulate consumption. This is why monetization of fiscal deficits will lead to inflation.

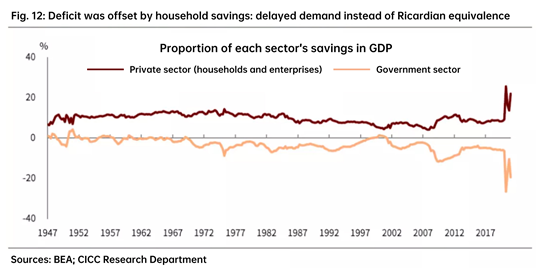

Why didn’t excessive money issuance discussed in the past decades cause global inflation? The main reason is that the money issued in the past decades was endogenous money through credit expansion. This means the money was borrowed, not free. In other words, today’s cash flow will increase because of credit, but tomorrow’s will drop because the debt needs to be paid off.

Therefore, we should be aware of the difference between endogenous and exogenous money. History shows that the main problem brought by excessive supply of exogenous money is inflation, such as the inflation upswings that occurred during 1960s and 70s. In contrast, the main problems associated with excess endogenous money supply are asset bubbles (especially real estate bubbles) and financial crisis. Typical examples include the crash of the US stock market in 1929 and the US subprime mortgage crisis in 2007 and 2008, both a result of unsustainable debt brought by credit expansion.

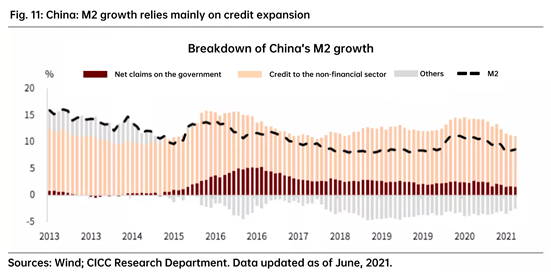

The ongoing upward trend of China’s financial cycle in the past decades is caused by excess endogenous money supply. Following the National Financial Work Conference in 2017, China stepped up financial regulation, which slowed down credit growth and lowered macro leverage ratio. But this time, to provide relief during the pandemic, China injected money mainly through credit expansion, which is fundamentally different from what happened in the US, where half the money was supplied through fiscal policy. Indeed, as the pandemic has been brought under control, the US M2 growth rate has started to drop, yet fiscal investment still contributes a huge part to such growth.

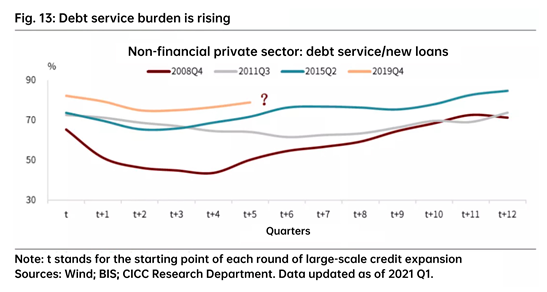

Specifically, in terms of household savings rate, with the pandemic under control and economic activities back on track, excess savings of US household are expected to fall, which can boost consumption. China initially relied mainly on credit expansion. Now its debt service burden has come to a turning point where the ratio of debt service to new loans is rising. In other words, capital is flowing from the real economy to banks. This is tight credit brought by debt expansion, which explains why currently China’s economy is weak in investment and consumption.

IV. FROM REBOOTING TO RESTRUCTURING

Recently, the US has seen its Treasury yields falling, dollar appreciating, and cyclical stocks dropping. There are two explanations for this phenomenon. One is concerns over the pandemic. The other is that the FOMC meeting in June signaled a speedier withdrawal of QE policies, but most investors agree with the Fed’s view that “inflation is transitory” and with this expectation in mind, believe that the Fed will take measures to control inflation; as a result, long-term interest rates are falling whereas the short-term rates are rising.

But the problem is whether reflation trade is really over. Based on the previous analysis, inflation is not a temporary phenomenon, and US inflation in the medium term might be higher than expected. As a result, money supply will be tightened, leading to credit crunch in the US and the world and bringing shocks to the emerging markets. This possible increase in risk-free rates is a key factor that drives the change in the valuation of the US stock market.

Indeed, if we look at the inverse of the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 or the earnings yield, it resembles that in the dot-com bubble period in 2000. But why does today’s US stock market look less risky? It’s because interest rates remain rather low. Although the implied stock market return is low, it is still attractive to investors compared to interest rates. Therefore, the key factor for assessing the prospect of the US stock market is the risk-free interest rate, namely, inflation.

For China, the critical issue is how to resolve debt risks. One way is through monetary easing. The problem is whether our easing policy will be constrained by US monetary tightening. To keep China’s monetary policy independent, foreign exchange rates need to be more flexible.

However, a more flexible foreign exchange rate alone may not be enough, since too much volatility is not good. It needs to be coupled with macro-prudential or even fiscal policies. Therefore, under the influence of the debt cycle, China’s risk-free interests would follow a downward trend. But for the stock market, what matters most is how to address debt risks and assess what impacts it will make on credit spread or risk premium.

Overall, the trend of China’s macro policy is “tight credit, loose monetary policy and expansionary fiscal policy”. Tight credit means two things: first, the market’s own debt cycle; second, macro-prudential policies, like the three red lines regulating real estate financing.

Recently, the central government has been emphasizing full implementation of long-term mechanisms to regulate the real estate sector. In my understanding, “full” means property tax would be included. Specifically, the key to solving the debt issue is to address the debt of real estate development firms and the implicit debt of local governments related to real estate activities in a more general sense.

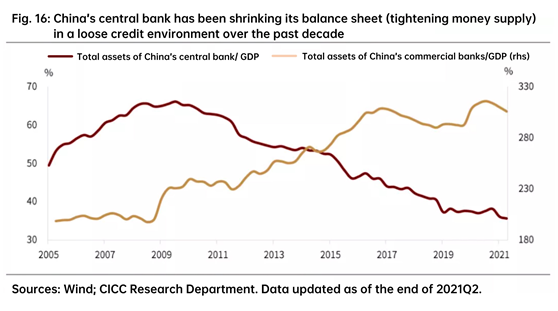

Under this background, how to implement loose monetary policy and expansionary fiscal policy? Over the past decade, compared to China’s GDP, China’s commercial banks have been expanding their balance sheets while the central bank has been reducing its own, which is the exact opposite of what has been occurring in the US. Looking ahead, one way to deleverage or tighten credit while avoiding harm to the economy is to let the central bank and fiscal policy play a bigger role. But due to various reasons, the room for fiscal expansion within the budget might be limited whereas quasi-fiscal operations, or expansionary fiscal policy with Chinese characteristics should be paid more attention.

As for public investment in areas that can both promote economic growth and improve income distribution, such as scientific and technological innovation, green transition, common prosperity, and rural revitalization, where does the money come from? One way of quasi-fiscal operations is to ask financial institutions to concede profits to the real economy.

One notable move is the release of new performance evaluation method for commercial banks by the Ministry of Finance. Previously, these institutions were evaluated based on four indicators: profitability, operational growth, asset quality and solvency. Under the new approach, serving national development and the real economy has become the top priority, development quality comes next, followed by risk control and operational efficiency.

This means that given the new situation, China defines banks not only as commercial institutions, but also institutions that need to transfer profits to the real economy through methods like inclusive finance. Some surveys show that in commercial banks, the proportion of inclusive finance loans in new loans has risen significantly.

As for CBDC, will it be a tool for the central bank to expand its balance sheet? Even if the answer is no, if the general public could hold CBDC, government financing cost could decrease.

At present, government bonds are mainly held by institutional investors whose decisions are highly responsive to changes in interest rates, even if it’s only a few basis points. The general public, however, is much less sensitive to interest rates and is willing to accept a low rate to hold safe assets. At present, commercial banks benefit from revenues generated by safe assets (bank deposit). In the future, if CBDC becomes a new safe asset and payment instrument, the central bank will gain more profits and commercial banks less, which will bring more revenue to the government directly or indirectly.

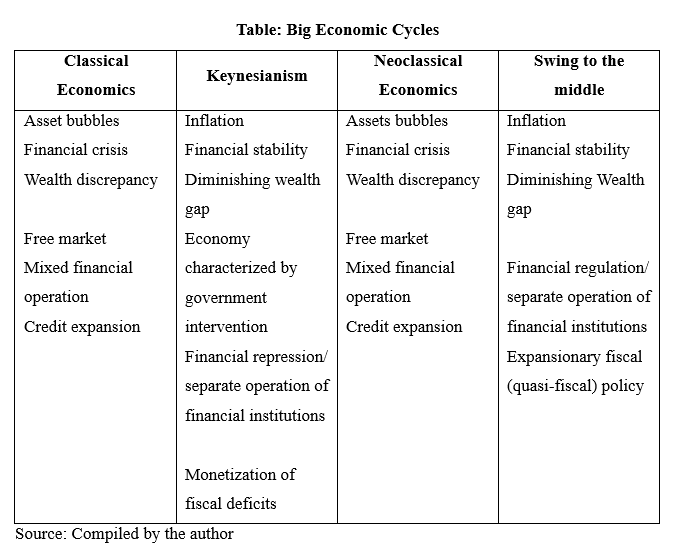

All in all, back to the topic of change and restructuring, we need to put recent economic development, especially the shock of the pandemic, into a long-term perspective. In my book The Approaching Financial Cycle, I put forward some thoughts on economic thinking, policy framework and economic cycles. The global financial crisis set off the reflection on over-liberalization and financial expansion. As a result, financial regulation was strengthened. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of fiscal policy and put the global economy on the track towards a historic transition. Theoretically, this shows the pendulum swinging between classical economics that believes in free market and Keynesianism that advocates government intervention to resolve market failure. But theory comes from reality, the transition reflects changes in the main contradictions of economy and society.

Before the 1930s, classical economics, as the dominant school of economic thought, promoted free market, mixed operations of financial institutions, and credit expansion, which resulted in asset bubbles, wealth discrepancy and the financial crisis in 1929. After the second world war, Keynesianism became the mainstream economic theory, advocating government intervention, financial repression, separate financial operation, and monetization of fiscal deficits. As a result, the financial system was stabilized and the wealth gap was diminished, but inflation became a huge problem.

Since the 1980s, the stagflation crisis prompted reflection on excessive government intervention. With the theoretical support of neoclassical economics, free market dominated again and the financial sector returned to mixed operation and credit expansion. Asset bubbles and wealth discrepancy emerged again in the past few decades, and so did the financial crisis.

After the 2008 financial crisis as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, the pendulum of economic thought swings to the middle, which is a fundamental change. In the financial sector, the basic framework has been made clear, which is to strengthen regulation and separate operation. Under this big cycle, enhanced regulation of digital economy and expansionary fiscal policy mean that there will be less risk of financial instability, more upward pressure of inflation whereas the wealth gap between rich and poor is expected to shrink.