Abstract: In this paper, the author argues that the crux of China’s economic slowdown is the spatial misallocation of resources. Market force leads the population and labor to coastal areas and major cities, while administrative forces channel them in the opposite direction toward inland China. This has given rise to a series of problems including sluggish production factor accumulation, weak growth in total factor productivity, and high government debt ratio in lagging areas. To deal with these problems, the author suggests the government improve resource allocation across regions to achieve higher economic efficiency and balanced development.

I. BEHIND CHINA’S SLOWED ECONOMIC GROWTH ARE INSTITUTIONAL AND STRUCTURAL BARRIERS: SPATIAL MISALLOCATION OF RESOURCES

No consensus has been reached as to the reasons behind the phased decline of China’s economic growth in the medium to long run. But most scholars would agree that despite cyclical factors at play, institutional and structural barriers take most of the blame.

Theoretically speaking, there are two sources of economic growth: accumulation of production factors and increase of total factor productivity (TFP).

If we look at the accumulation of production factors, on one hand, China is losing the demographic dividend; on the other hand, excessive investment has caused returns to go down, and the ratio of investment to GDP has been declining in recent years, which makes investment less of an engine for growth. In addition, urbanization of land has happened at a faster pace than urbanization of population in China, especially in the central, western and northeastern parts of the country where there are large population outflows, according to my research.

Parallel to the slowdown of factor accumulation is sluggish growth in TFP. Years ago, when I was examining firm-level data, I found that the year of 2003 marked a critical turning point in TFP growth and resource allocation efficiency in China.

These factors combined have slowed China’s economic growth, and the crux here is what I refer to as “spatial misallocation of resources”: misallocation of economic resources between urban and rural areas and across regions has stemmed economic growth and efficiency in China. This is a new perspective that my team offers to the research on China’s economic growth.

First, let me explain the importance of geographical locations in economic growth. Since the launch of reform and opening-up, especially starting from mid-1990s, China became increasingly engaged in globalization, putting its coastal areas with ports at an advantageous position to achieve economic growth.

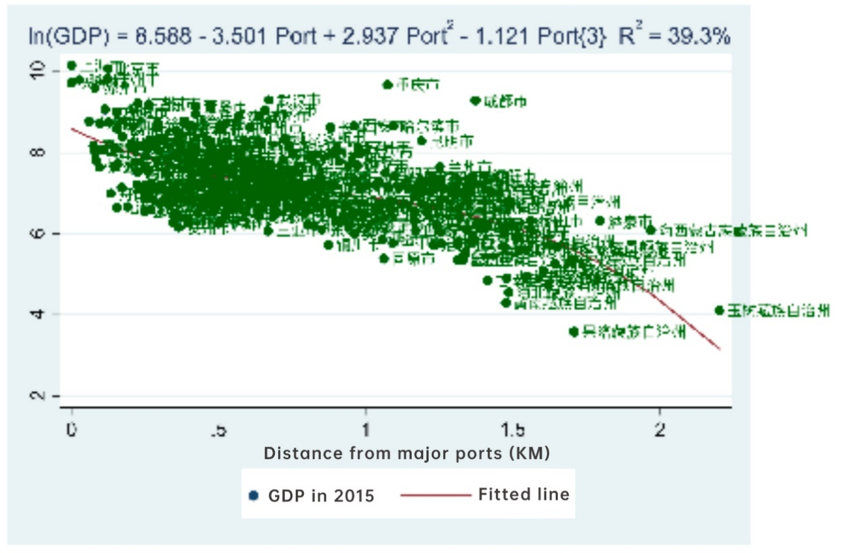

We have selected three major seaports, Tianjin in northern China, Shanghai in eastern China and Shenzhen/Hong Kong in southern China, and studied the relation between the GDP of various centrally administered and prefecture-level cities across China in 2015 and their geographical distances from the three ports. Our research shows that cities located farther away from the ports tend to have a smaller economy. This factor alone explains almost 40% of the gap between cities in economic scale; adding other relevant factors into the model will only increase the percentage to 70%. In other words, this geographical factor alone accounts for a larger part of regional difference in economic scale than all other factors combined.

Fig. 1 Negative correlation between the GDP of a city and its geographical distance from major ports

Note: The green dots represent various cities across China.

Source: LU Ming, LI Pengfei, ZHONG Huiyong, 2019

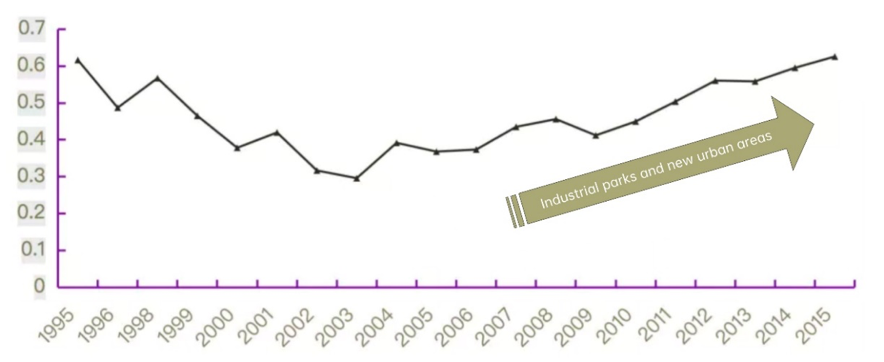

The allocation of land, among all the economic resources, has the biggest impact on the Chinese economy. Before 2003, the proportion of central and western regions in China’s total land supply had been declining, which corresponds to the population outflows from these areas. But since 2003, while population was still moving towards coastal areas, central and western regions have been enjoying a bigger share in the country’s land supply.

Fig. 2 Share of central and western regions in China’s total land supply going up continuously since 2003

Source: China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook; LU Ming, ZHANG Hang, LIANG Wenquan, 2015; HAN Libin, LU Ming, 2018

In central and western China, especially medium- and small-sized cities, a large proportion of land has been used to build industrial parks and new urban areas which were deemed to be able to facilitate economic growth. But it turns out that these projects have actually reduced investment returns and pushed up government debt.

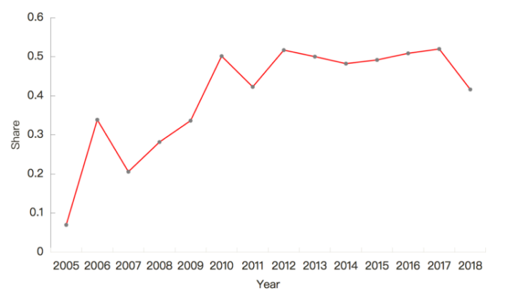

If we look at urban investment bonds, a form of local government debt, before the central government started to help local government in less developed regions to solve their debt problems, urban investment bonds issued in central and western China accounted for as high as 50% of the national total, and the percentage was still on the rise. In other words, local government debt grew faster in regions that lacked momentum for economic growth.

Fig. 3 Share of urban investment bonds issued by local governments in central and western China in national total on the rise

It’s important to note that the financial market has also played a role in this process. Because local government debts are endorsed by the local and central governments, local government can easily obtain credit on the financial market. However, borrowing by local governments in less-developed regions could be very risky, hence the higher financing cost.

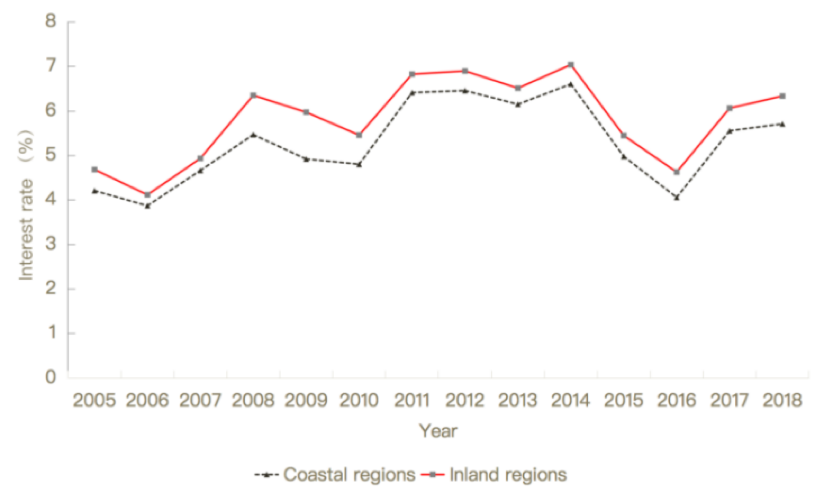

We’ve compared the interest rates at which urban investment bonds were issued by local governments in less-developed regions in inland China and in coastal areas. In general, financing costs for the local governments had been going up continuously until recent years, while the interest rates in inland cities were remarkably higher than in coastal cities.

That is to say, regions with weaker growth momentum have been allocated more land and used it for mortgaged financing, raising massive debts at higher costs.

Fig. 4 Urban investment bond issued at a higher interest rate in inland regions than in coastal regions

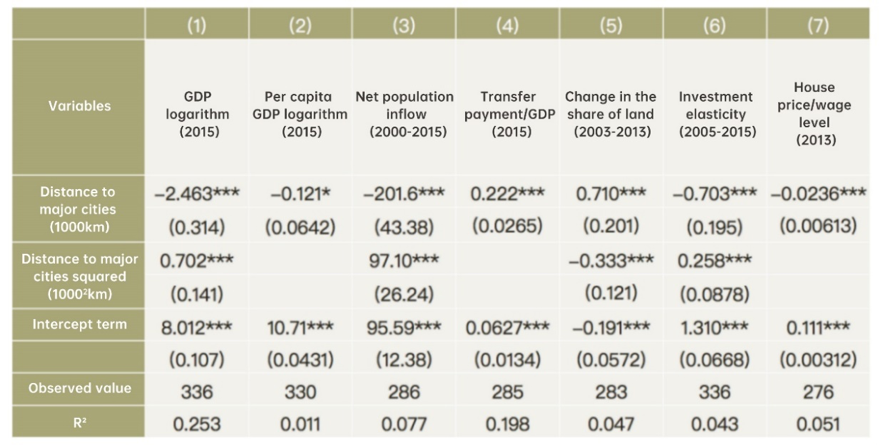

In an article in 2019, we analyzed the impact of geographical locations on various economic variables and found the following -

As a result of market-based resource allocation, regions farther away from ports have smaller economies, lower per capita GDP, and lower net population inflow or even population outflow. Yet, as a result of government-led resource allocation, in such regions, transfer payment accounts for a higher proportion of GDP, and they have more additional land supplies, or in other words, these regions have received more government resources. But investment elasticity in these regions is lower, which means each unit of investment contributes less to GDP growth. In addition, population outflow combined with increased land supply and house building have lowered the house price in these regions. Things in coastal regions are a completely different story, where GDP and per capita GDP are higher, people are flooding in, investment is more effective in driving GDP growth, but fewer government resources are allocated there, and with large population inflow and restricted land supply, the house prices are higher.

In general, market forces are driving resources and population toward coastal regions in eastern China, while the government is channeling resources toward central and western China. This has brought about problems like inefficient investment and widened gap in regional house prices. We’ve also found that regions located farther away from national central cities have lower GDP and per capita GDP as well as net population outflow; yet they have received more transfer payment and land supply, investment there is less effective in driving GDP growth, and the house price is lower. This again shows that the market and the government channel resources in opposite directions.

Table 1: Impact of the distance from national central cities on economic variables

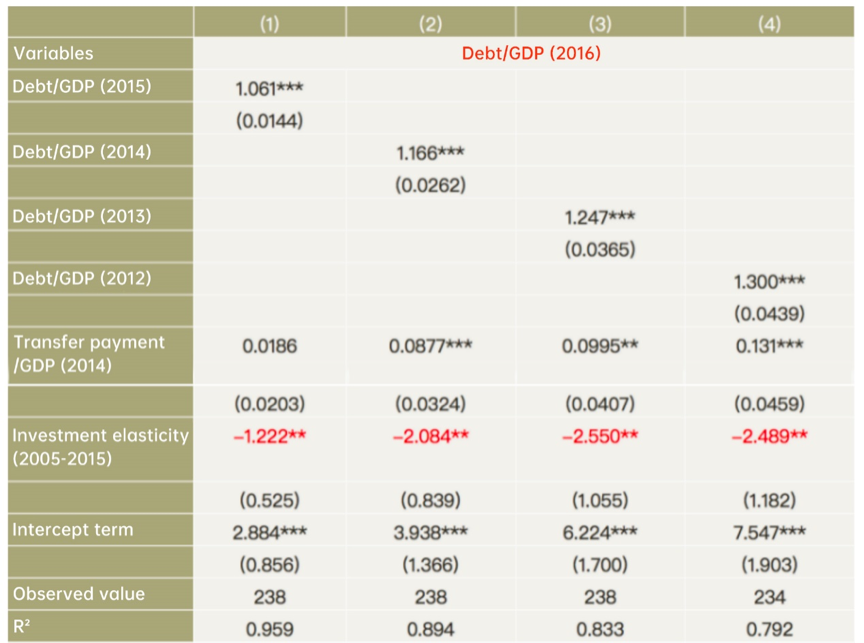

Debt-wise, we have examined the level of the debt-to-GDP ratio of local governments up to 2016. The results show that on one hand, there is a positive correlation between historical and current debt-to-GDP ratios, which means that cities that were heavily indebted mostly remain that way; on the other hand, the relationship between the investment elasticity coefficient and the debt-to-GDP ratio merits attention—local governments in areas where investment is more effective are usually less indebted.

Table 2: Factors shaping the debt-to-GDP ratio of local governments

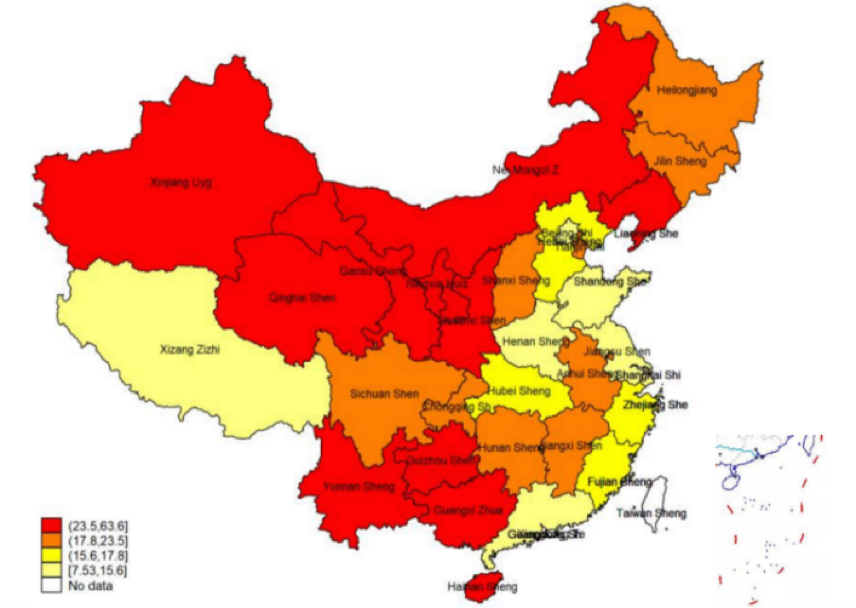

As mentioned above, in regions farther away from major ports and cities, investment plays a restricted role in driving GDP growth. More investment and construction projects have increased local government debt and elevated the debt ratio. By analyzing the debt ratios of local governments across China, we found that in 2017, provinces in central and western China were more heavily indebted. Among coastal provinces, Liaoning and Hainan were the only two with debt ratios comparable to levels in central and western regions.

Fig. 5 Debt ratios of local governments across China, 2017

While Liaoning locates in the coastal area, as one of the rust-belt provinces in northeastern China where the national strategy for revitalizing old industrial bases was implemented, it received a level of policy support similar to that given to provinces in central and western China . As a result, many new urban areas and industrial parks were built, and that explains the high debt ratio in the province.

Guizhou is another province with severe debt problems. Much media attention has been paid to Guizhou’s economic growth, but little to its debt ratio. As a matter of fact, the province has long seen massive investments with low returns, and now ranks among heavily indebted areas.

II. Improve the spatial allocation of resources and empower the new development paradigm of “dual circulation.”

The above-mentioned phenomenon reflects a mid-to-long-term problem, that is, a spatial misallocation of resources. It is therefore necessary to improve the spatial allocation of two factors—production factor accumulation and TFP—that spur economic growth over the medium and long run.

In terms of production factor accumulation, in the face of disappearing demographic dividend, China can improve efficiency of labor utilization by promoting labor mobility, thereby prolonging the demographic dividend. When talking about labor mobility, it is also necessary to take children into consideration and make efforts to reduce the number of left-behind children in China.

The key factor causing the predicament that urbanization of land is faster than urbanization of population lies in the misallocation of land resources. Now the central government has made it clear that land allocation must be consistent with the direction of population flow, which I call "land follows people". This can alleviate the spatial mismatch between land and population flow.

The key to address excessive investment and low investment efficiency is to make investment in accordance with the comparative advantages of the regions, a way to increase the return. At the same time, public investment, such as investment in public services and infrastructure, must be in line with the direction of population flow, so as to adapt to people’s needs for a better life. In addition, in the investment in public services, it is necessary to solve the problem of left-behind children, as doing so can also increase future supply of human capital.

In terms of TFP, one way is to improve the spatial efficiency of resource allocation; the other is to accelerate the accumulation of human resources through investment in public services, especially in the field of education, so as to improve the quality of the next generation.

What changes will these measures bring? We performed a series of data analysis to answer this question. On the whole, if China can optimize the spatial allocation of economic resources, it can successfully establish the ‘dual circulation’ new development pattern. I will present my analysis from four aspects, i.e. economic growth, balanced development, structural optimization and international balance.

1. Economic growth

Research shows that assigning more construction land quotas to inland areas has reduced the land supply in developed areas, inhibiting the allocation of land and labor to places with high productivity and resulting in the decline of national GDP and TFP. Moreover, when economic resources are tilted toward inland regions, although the GDP gap between coastal and inland regions has narrowed, the level of income inequality across the country has increased. In the case of resource misallocation, when the flow of inland population to higher-income coastal areas decreases, average income falls as a consequence. In other words, such a spatial development strategy has resulted in a loss of both efficiency and equality.

However, according to our recent estimation, removing preferential allocation of land quotas to inland regions can boost the national GDP by 2.4%, TFP by 7.3%, and lead to a rise in per capita income among locally registered labor force population across China, with the increase ranging between 1 to 2% in less-developed areas. This number is calculated based on the registered part of population in the region and would be much higher if we only consider migrant population.

We also believe that China can achieve a more efficient and balanced development between rural and urban areas and across regions if inland regions no longer receives excessive land quotas, which can not only contribute to the new development pattern with the domestic market as the mainstay, but will also promote the international circulation of the Chinese economy.

I mentioned in a study a few years ago that if China can improve the spatial allocation of population and land, that is, encouraging labor inflows into and increasing land supply in coastal areas, the country will see the prices of land and housing go down. Consequently, wages will also drop, so labor costs will fall. This is because housing has become a very important part of the cost of living in coastal areas.

In addition, in terms of agriculture and rural development, if the rural labor force can settle in cities with no barriers, rural areas can be used to develop large-scale and modern agriculture, which can help rural revitalization and reduce the production cost of agricultural products, enhancing the international competitiveness of China’s agriculture sector.

2. Balanced development

In terms of balanced development, our recent research shows that China will move towards balanced development at the per capita level while ushering in economic agglomeration.

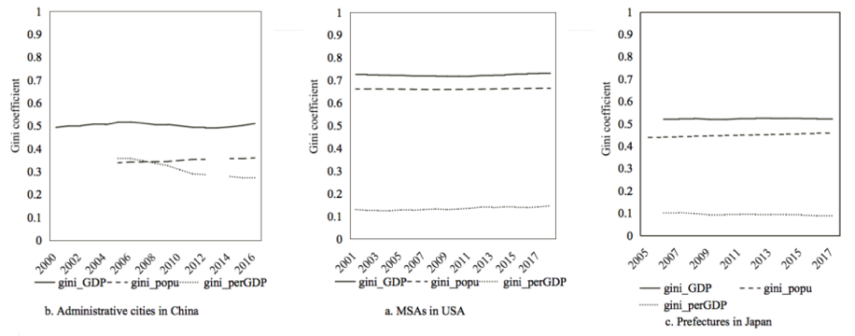

Comparing the data of China, the United States and Japan, we can see that cities in the US vary greatly in GDP and population size, but as their economy and population are simultaneously concentrated in a few regions, the difference in per capita GDP between regions is rather small. Like the United States, Japan’s GDP and population are highly concentrated in a few areas, and the two are in line with each other, so the difference in per capita GDP among cities is also very small. The difference in GDP among Chinese cities is roughly the same as that in Japan, but the difference in population size is much bigger than that in Japan, not to mention the United States. As population agglomeration has not kept up with economic agglomeration, the difference in per capita GDP among cities in China is much higher than that of the United States and Japan.

Fig. 6 Comparison of GDP, per capita GDP and population of cities in China, the US and Japan

Source: Li and Lu, 2021

The good thing is that China’s population agglomeration is increasing, which has reduced regional disparity in per capita GDP. In other words, China's economy and population have become more concentrated in a few regions. At the same time, China's economy is moving towards balanced development at the per capita level. In a recent analysis, we predict that if China can achieve relatively free flow of population between regions by 2035, the difference in per capita GDP among cities will be reduced to the level of the United States and Japan today.

3. Optimizing structure

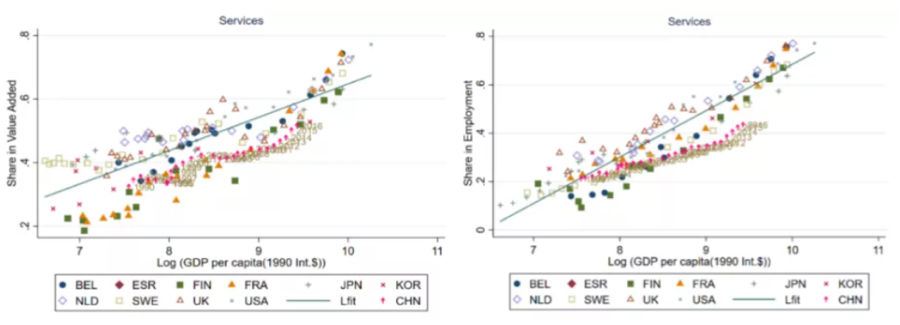

The inconsistency between China's population agglomeration and economic agglomeration has suppressed the development of the service sector. We see that in OECD countries, with the development of the economy, the share of the service sector in GDP and employment is on a continuous rise, but China’s share is substantially lower than that in developed countries at a comparable development stage. We believe this is because the current spatial allocation of China's population lags behind the country’s economic development, and policies in China have restricted the process of urbanization and population inflows to big cities.

Fig. 7 Shares of service sector in GDP and employment in OECD countries and China

Sources: Zhong Yuejun, Lu Ming, Xi Xican, 2020

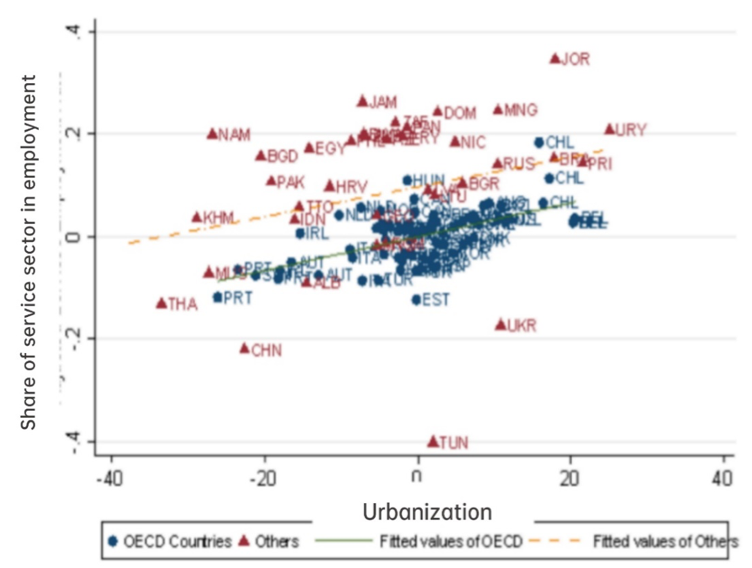

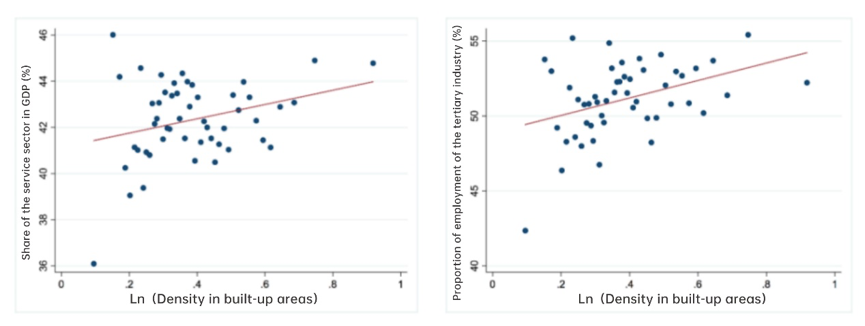

When looking at the relationship between urbanization and the service industry, we can see that a high level of urbanization increases the proportion of the service industry in GDP. When we compare cities of different scales, we find that the tertiary industry accounts for a higher proportion in GDP in big cities than in the small ones. In addition, the high population density also helps increase the proportion of the tertiary industry in GDP and employment.

Fig. 8 How urbanization affects the share of service sector in employment

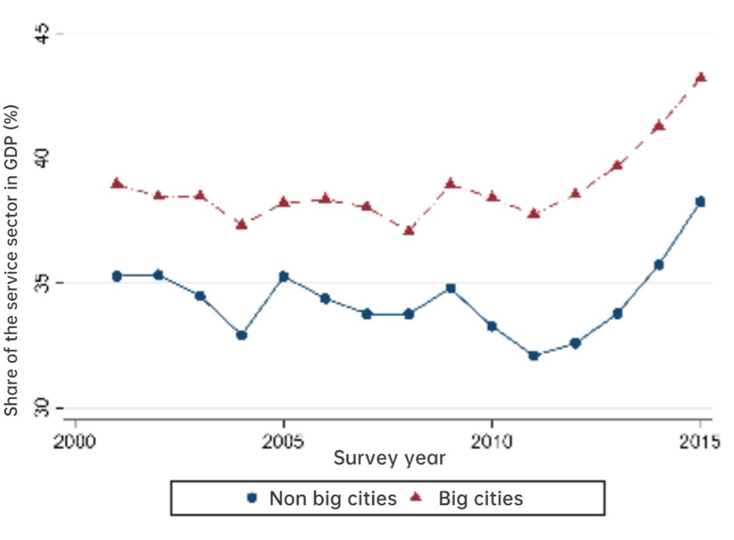

Fig. 9 How the scale of cities affects the share of service sector in GDP

Fig. 10 How population density affects the share of service sector in GDP

Currently, allocation of production factors, especially labor, is facing many problems in China. For one thing, the urbanization rate is low, and for another, many cities treat non-local labor differently. In addition, the supply of land is tilted towards regions with population outflow, leading to a sharp decline in the urban population density.

Results of our 2020 study show that intensive urban development and the settling of the migrant population in cities are beneficial to the development of the service industry. If China can increase the urbanization rate by ten percentage points, and the migrant population can settle in the places where they live and work, that is, having the same household registration status, enjoying the same public service and adopting the same consumption pattern, the proportion of China's service industry in GDP can increase by 3 to 5 percentage points, given that the land supply slows down and the fall of population density decelerates by half.

We further studied the impact of urbanization and mega-urbanization on structural optimization. We found that if China’s urbanization rate can reach the average level of other countries at the same stage of development, the share of China's service industry in total employment can increase by about 4%, and total output can increase by 10.7%.

We also studied the distribution of population and land resources in small cities and large cities, and found that large cities have stronger comparative advantages in developing service industries due to the income effect and scale of economy. Therefore, if we can allow free flow of labor by reforming the household registration system and encouraging labor flow to the periphery of big cities, the proportion of the service industry in total output will rise by 2.5 to 3.5 percentage points, the income gap between cities will decrease by 14%, total output will rise by 10%, and social welfare can increase by 7.4%. At the same time, by increasing the land supply in big cities, restoring their proportion in total land stock to the 2003 level, and aligning the land supply with the flow of population, the proportion of the service industry in total output can further rise by one percentage point, and the total output can increase by 3.6%.

4. International balance

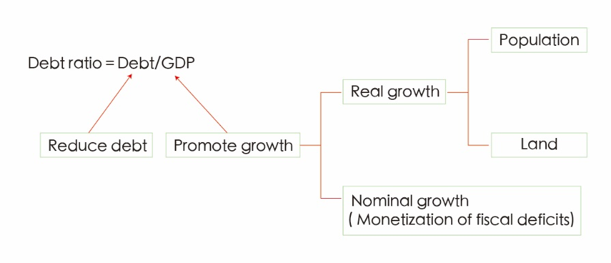

China is running a race between reform and stagflation. At present, China's government debt ratio is at a relatively high level, and there is a large amount of domestic debt. There are only two ways to reduce the debt ratio. One is to reduce the debt itself, which is difficult because a large number of local governments are still borrowing new debt to repay the old; the other is to increase GDP. There are two forms of GDP growth. The first is real growth, and the second is nominal growth, accompanied by the monetization of fiscal deficits.

Fig. 11 Two ways to reduce debt ratio

What this article proposes is that China should increase the real economic growth by optimizing spatial allocation of production factors such as labor and land. Otherwise, it will have to reduce the debt ratio by improving nominal growth, but this will bring about inflation. If inflation becomes a mid-to-long-term trend, the RMB will face depreciation pressure. Under this pressure, people will want to exchange RMB for foreign exchange, which can cause the decline of foreign exchange reserves. As China has not yet fully lieberalized its capital account and capital flows are not free, this will inevitably hinder the process of RMB internationalization. In fact, the trend of RMB depreciation has taken shape after 2015, and the status of RMB as an international payment currency has weakened compared to a few years ago. Therefore, China needs to increase the quality and speed of its long-term economic growth so as to support RMB internationalization and international circulation.

Reference:

Fang Min, Libin Han, Zibin Huang, Ming Lu, and Li Zhang, 2021, “Regional Convergence or Just An Illusion? Place-based Land Policy and Spatial Misallocation,” working paper.

Libin Han and Ming Lu, 2017, “Housing Prices and Investment: an Assessment of China's Inland-Favoring Land Supply Policies.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 22(1), pp. 106-121.

Pengfei Li and Ming Lu, 2021, "Urban Systems: Understanding and Predicting the Spatial Distribution of China's Population," China & World Economy, 29(4): 35-62.

Ming Lu, Xican Xi and Yuejun Zhong, 2021, “Urbanization and The Rise of Services: Evidence from China,” working paper, Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Fudan University.

Chen Chang and Ming Lu, 2017, “The Death of New Towns: Density, Distance and Debt,” China Economic Quarterly, 16(4):1621-1642.

Libin Han and Ming Lu, 2018, "Mismatch of Supply and Demand: Solving the Mystery of the Division of China's House Price Rising," The Journal of World Economy, 10, pp.126-149.

Ming Lu, Pengfei Li and Huiyong Zhong, 2019, "A New Era of Development and Balance-The Political Economy of Space in 70 Years of New China," Journal of Management World, 10, pp.11-23.

Ming Lu and Kuanhu Xiang, 2014, "Resolving the Conflict between Efficiency and Balance: On China's Regional Development Strategy," Comparative Economic & Social Systems, 4, pp. 1-16.

Ming Lu, Hang Zhang and Wenquan Liang, 2015, "How the Supply of Land Biased towards the Midwest Pushed up Wages in the East," Social Sciences in China, 5, pp. 59-83.

Haolong Xu and Ming Lu, 2021, "Solving the Dilemma of China's Agriculture: Agricultural Scale Operation and Competitiveness in an International Perspective," Academic Monthly, 6, pp. 58-71.

Yuejun Zhong, Ming Lu and Xican Xi, 2020, "Agglomeration and Service Industry Development: Based on the Perspective of Population Spatial Distribution," World of Management World, 11, pp. 35-47.

Yuejun Zhong, Xican Xi and Ming Lu, 2021, "Space, Structure, and Growth: A Spatial Equilibrium Analysis of Population and Land Reallocation Effects," Working Paper, Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Fudan University.

DOWNLOAD PDF