Abstract: In this paper, the author points out that the Chinese economy will suffer from severe demand-side shock when the population peaks and ages. To tackle this challenge, he suggests that China increase efficiency of resource allocation among industries and firms, improve income redistribution and build the social welfare system to support consumption, and optimize childbearing policy to achieve desired fertility rate.

I. Short-term shocks may accelerate long-term trends

History shows that short-term shocks such as financial crises and economic recessions could change a long-term trend, not necessarily halt it, but may reinforce or accelerate it.

In fact, it is quite common that short-term shocks accelerate along-term trend, because crises can amplify weaknesses and facilitate market clearing. A typical example is secular stagnation, a concept espoused by the former US Secretary of the Treasury and Harvard University Professor Larry Summers. The world economy has in fact long entered the trend, but the financial crisis in 2008 made secular stagnation a reality, rushing the economy into a state of low inflation, low interest rates, low growth, and high debt against the background of population ageing.

As early as in1937, Keynes proposed that slowed population growth can cause economic disasters. In 1938, Hansen echoed Keynes’ view and for the first time raised the concept of secular stagnation, which he considered to be a long-term historical trend unless a country can improve its income distribution, a politically infeasible task in his opinion. Interestingly, Hansen was an economic adviser to President Roosevelt, but he did not know that Roosevelt’s New Deal would change the income distribution in the United States and mark the beginning of a welfare state. Keynes, too, did not foresee that, just a few years later in 1941, the United Kingdom would publish the groundbreaking Beveridge Report which ushered in a new era in the history of social security system. Both economists anticipated the occurrence of secular stagnation, but the development of welfare states at that time in the United States and the United Kingdom delayed this long-term trend, and prevented secular stagnation from taking place.

In the field of macroeconomic research, there is the concept of hysteresis, that is, potential growth of a period is related to historical development, and especially to various cyclical interruptions. Japan is the most representative example. Looking at Japan's growth curve over the years, one can find that the potential growth rate, the actual growth rate, and the total population all show a downward trend. In the early 1990s, the bursting of the economic bubble in the country caused a short-term shock. At the same time, Japan encountered its first demographic turning point, where the working-age population reached its peak and entered negative growth from then on. Under the double shocks, Japan's potential growth rate began to drop sharply. In 2007, when the financial crisis began to emerge, Japan saw its second demographic turning point where the total population peaked and began to decrease, setting the stage for the second encounter between long-term trends and short-term shocks. Since then, the Japanese economy has not only witnessed a negative growth rate of over five percentage points, it has often seen a "negative growth gap", that is, the actual growth rate being lower than the potential growth rate.

As a textbook case of secular stagnation, Japan provides a direct reference for economies developing the “Japan disease”. In September 2019, Professor Summers warned that the US was only one recession away from “Japanification”. A few months later, the COVID-19 pandemic made his words a reality.

II. Long-term trend: population ageing constrains consumption growth across all age groups

What determines the long-term consumption trend? Population.

China’s working-age population reached its peak in 2010, the first demographic turning point. Its total population will peak around 2025, which will be the second turning point.

After the working-age population reached its peak, China’s economy suffered a supply-side shock. We expect that when the total population peaks, the economy will encounter a severe demand-side shock. The key question now is whether this demand-side shock will come earlier because of the COVID-19 shock.

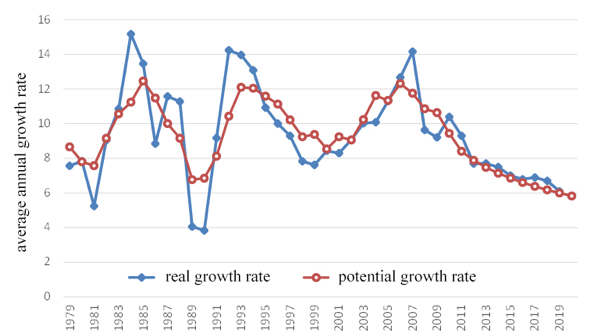

China's working-age population peaked in 2010 and then began to decline, which reversed the trend of labor supply, human capital improvement, the rate of return on capital, and the allocation of resources, leading to a decline in the potential growth rate. The potential growth rate curve in Figure 1 was an estimation made in 2012. From observing the potential and the actual growth rate curves, we may notice an interesting phenomenon: the two rates did not move in exact tandem before 2010, even though the data used are real historical data, but the two exhibited the same trajectories after 2011 even though the data are forecasts. More than proving the forecast of the potential growth rate at that time was accurate, it also shows that after 2011, China did not encounter a demand-side shock during economic slowdown and strong demand ensured the realization of the potential growth rate. However, at the next turning point, what the economy will encounter may be precisely the shock from the demand side.

Figure 1: China's actual growth rate and potential growth rate in recent years

In fact, demand-side shocks can also come from the supply side. For example, the decline in China’s comparative advantage can lead to export shocks and weak willingness to invest. The slowdown in economic growth can also slow down income growth and cause sluggish consumption. The second demographic turning point has increasingly suppressed household consumption. In general, population ageing can curb consumption through three effects. The first is the total population effect. Population means consumers. When other conditions remain the same, a fast-growing population will lead to strong growth of consumption, while a shrinking population could cause declining consumer spending. The second is the income distribution effect. Because the marginal propensity to consume of the rich is low, and that of the poor is high, income polarization will lower the general propensity to consume and cause oversaving. The third is the effect of age structure. As population ages, a natural tendency to suppress consumption may emerge. An analysis based on urban household survey data could help illustrate the point.

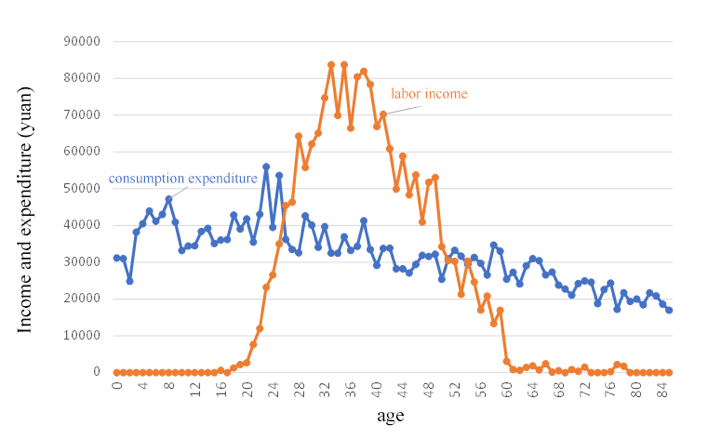

Let's look at Figure 2 to understand these effects. As shown in the figure, labor income is only generated by working population aged 20 to 60, while consumption happens across all age groups. Data show that the highest level of consumption occurs during adolescence. This is because as population ages, children become scarce, at which point, the law of scarcity will take effect, not only motivating parents and grandparents to spend more for their children, but also substantially driving up the market and social costs of childrearing and education. However, consumption growth generated this way cannot be sustained as the number of children continues to decline. As for individuals of working age groups who are creating labor income, their real consumption is not high at all because they have to pay pension contributions, have precautionary savings, and spend money for their children. Middle-aged workers are actually paying directly for today’s retirees under the current pay-as-you-go system, and at the same time they have to save more for old age because they know they may face a different pension scheme when they retire due to the change in population dependency ratio, which further inhibits consumption. Seniors have low income and low marginal propensity to consume, so their consumption is naturally not high. It can be seen that population ageing affects consumption growth of all age groups. This is what we may encounter in the future.

Figure 2: Labor income and consumption expenditure of different age groups

III. Short-term shock: pandemic-induced unemployment still exists and acts as a constraint on demand

On the surface, the economic recovery we are currently ushering in is a V-shaped one brought about by the inverted V-shaped epidemic curve. But I think that the V-shaped recovery is not yet completed. As mentioned earlier, a hysteresis effect may occur, and the development trend may change due to this shock. A priority issue is to prevent the short-term shock from accelerating the long-term trend that had been developing slowly.

Unemployment rate can be used as an entry point to study the loss of income and the lagging recovery of consumption:

First, data show that China’s unemployment rate in February 2021 was 5.5%, reaching the highest point in the last five months. In other words, the unemployment rate did not show signs of returning to its original trajectory. According to our previous estimate, China's natural unemployment rate is 5%, and the part above 5% is the cyclical unemployment rate. From this point of view, the cyclical unemployment caused by COVID-19 still exists.

Second, according to the law of hysteresis, the natural unemployment rate will increase once hit by a short-term shock. Never waste a good crisis. For one thing, people could draw lessons from a crisis. For another thing, a recession can produce creative destruction that can force underperforming industries and enterprises to exit the market. However, it is precisely these industries and enterprises that employ the lower-skilled workers. Once the creative destruction takes effect, a large number of workers will find it more difficult to get jobs, and the natural unemployment rate will therefore rise. At present, we don’t know how much the natural unemployment rate has increased due to the creative destruction effect. Let’s say it has increased from 5% to 5.2%. The current unemployment rate of 5.5% is still above this value, indicating that cyclical unemployment still exists. Therefore, policy measures should strike a balance between protecting market entities and protecting workers’ income, rather than favoring one or the other.

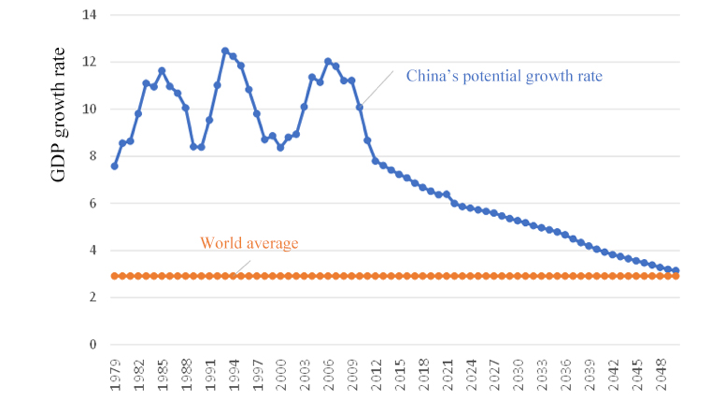

In the long run, China's growth rate will inevitably decline. Many economists believe that China's economic growth will fall to the meanvalue, that is, the world average level. There is no problem with the falling, the problem is when this will happen. If the growth rate falls in the near term, the size of the Chinese economy may never catch up with that of the United States. However, in the past 30 years, the world’s average growth rate was close to 3%. Using this data, it can be predicted that China’s growth rate will not fall to the world’s average until around 2050. As shown in Figure 3, we have confidence in China's long-term economic growth. It should be noted that this potential growth rate is predicted based on supply capacity. If demand is weak, it is possible that China’s growth rate will fall to the world’s average before 2050. Therefore, the key task at present is to ensure the demand side won’t be a constraining factor on China’s long-term growth.

Figure 3: China’s potential growth rate and the world’s actual growth rate over the past 20 years

IV. Prevent the short-term shock from accelerating the long-term trend

First, prevent inefficient resource allocation. China’s economic growth is increasingly relying on the improvement of total factor productivity, a necessary supply-side factor. But at this stage, China has encountered many difficulties and obstacles in this regard.

With diminishing demographic dividend and weakening comparative advantage, on the one hand, the Barassa Index (which measures comparative advantage) of China’s manufacturing industry has been on a downward trend since 2012; on the other hand, since 2006 the proportion of China's manufacturing industry in GDP has also declined. However, during this process, the declineof different enterprises and industries has happened at different paces based on their competitiveness and productivity. If we continue to provide support and subsidy to those uncompetitive enterprises that have lost comparative advantage, resource allocation will not be efficient.

On the other hand, some uncompetitive enterprises have exited the market, but new comers into the manufacturing industry have also decreased, causing the growth of the manufacturing sector to slow down. This type of industry restructuring is shifting labor from manufacturing to the service industry. In general, adjustment of industrial structure transfers labor from low-productivity sectors to high-productivity sectors. However, currently in China, the service sector, especially the consumer service industry, is has a relatively low productivity. Therefore, the shift of labor from manufacturing to the serviceshas actually led to lower efficiency of resource allocation and decreased total productivity. One of the challenges we face now is to stabilize the development of manufacturing industry.

How to do it? This also contains a dilemma. Many non-performing enterprises tend to seek protection, such as loans and preferential policies in order to survive. They may remain in the market for a very long time, and some even ask for government subsidies in the name of ‘upgrade’, which ultimately leads to inefficient resource allocation. In many cases, companies that should leave the market remain, including many zombie firms. This has caused sharp drop in productivity. Therefore, we must create the conditions for creative destruction, and ensure smooth market clearing, so that productive enterprises can better survive and grow.

Second, improve redistribution and establish a welfare state with Chinese characteristics. The proportion of welfare expenditure in OECD countries is significantly and positively correlated with labor productivity. The lesson from this is that if we can protect the special production factor, i.e. labor, at the social level, we then don’t need to protect the enterprises, or preserve firms with over capacity and low efficiency, or unnecessary jobs. We only need to protect the workers. Only in this case can creative destruction take effect; otherwise, it is very likely that zombie firms will be kept in the name of protecting jobs

In the short term, China needs to revive its economy from the pandemic’s blow; while in the long run, we need to build a welfare state with Chinese characteristics. Now is the best time to align the short-term task with the long-term goal. The per-capita GDP in China has exceeded the threshold of 10,000 USD, and if China is to become a moderately developed country in 2035, it has to achieve a per-capita GDP of 23,000 USD then. Generally speaking, the period during which the per-capita GDP increases from10,000 USD to 23,000 usually sees fast increase in social welfare expenditure and continuous growth in the proportion of government spending in GDP. In other words, China has entered the critical stage in building a welfare state. It should take measures to both address the pressing issue of post-pandemic consumption recovery and deal with the long-term challenge of consumption reduction caused by population ageing.

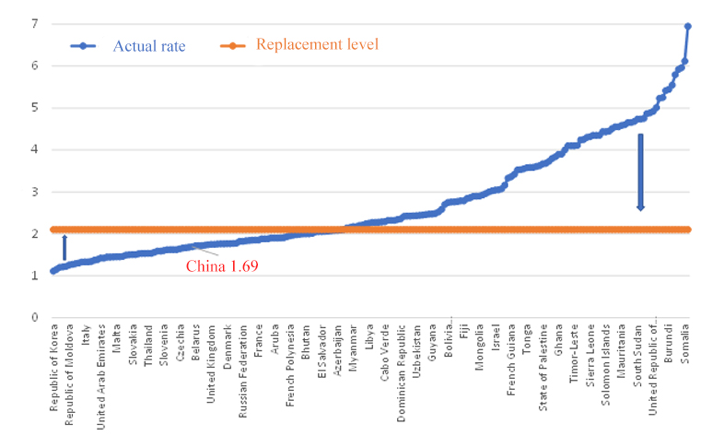

Third, to achieve population growth, China’s fertility rate has to be increased. The blue curve in Figure 4 represents the total fertility rates of different countries and regions, with some at as high as 3 to 4 or even 6 to 7 while some others lower than the replacement level of 2.1 or even below 1. However, a survey by the United Nations on childbearing willingness shows that people in all countries generally prefer to have two children, which in fact deviates from the actual number of children they have.

Figure 4: Actual fertility rates of various countries and the replacement level of 2.1

A vast body of literature has found that the decline in the fertility rate is almost irreversible. A recent article in The Lancet pointed out that the education of women and access to contraception explain 80% of the decrease in the fertility rate. Both factors are signs of social progress, and thus, irreversible, and we should not run against the trends. What we can do is to try and work on the remaining 20%. Recent studies show that environmental pollution and stress also significantly suppress fertility, which seems to leave almost no solution for us at all. In addition, a recent working paper authored by several young scholars at the People’s Bank of China (PBC), which attracted wide attention, cited an article published in Nature years ago suggesting that the fertility rate will rise again when the Human Development Index (HDI) of a country reaches a high enough level. But two stories followed after this article may suggest otherwise.

First, Cai Yong, a Chinese scholar working in the United States, wrote to Nature immediately after he read the article saying that the data processing method used was misleading as logarithmically transformed data could lead readers to expect an up-turn in the development-fertility relationship, which would not exist at all if the data is processed in a different way. That is to say, any reversal of fertility decline will be very difficult, if possible at all.

Second, one of the co-authors of this article later wrote another piece to make up for the flaw, saying that while the fertility rate in some countries was modestly improved, it was actually a “gender dividend” as a result of greater progress in gender equality. In other words, in these countries, the willingness of women to have children may have risen a little bit after their social status was elevated. However, this is not a universal phenomenon.

On the whole, we could not expect any substantial bounce-back in the fertility rate going forward. However, improvement in childbearing policies remains important, because our goal is not to resume a high fertility rate, but to move as closer as possible to the replacement level of 2.1. The most pressing task is to introduce substantive, effective and targeted measures to reduce the costs of childbearing, rearing, and education. Meanwhile, we have to learn to live with population ageing, and reap the dividends brought by this demographic trend by promoting lifelong learning, rolling out anti-discrimination rules in the labor market, improving labor participation, and building a more inclusive pension insurance system.

Download PDF at: