Abstract: By the basic definitions of financial stability, digital finance/fintech is transforming the way of providing financial services and changing the landscape of financial industry, while new financial service providers are bound to influence financial stability. Over a long run, fintech advances are expected to boost financial stability, including enhancing the financial system’s transparency and efficiency. And, the development of digital finance will bring about new topics and challenges to financial regulation, and lead to new characteristics in risks: first, there may be micro-financial risks; second, systematic financial risks may arise; third, regulatory gaps remain for fintech; fourth, higher digitalization of finance will pose new challenges to conduct regulation; and fifth, fintech will possibly weaken the efficiency of existing financial safety net.

In this regard, it is necessary to improve the regulatory system and enforce strict market discipline, in order to allow fintech to play a positive role in supporting the real economy and safeguarding financial stability. Specifically, there are six policy recommendations: First, work out the prudential regulation requirements to ensure full coverage of fintech business; second, establish the conduct regulation system to protect the market order; third, act in line with the activities-based regulation requirements to eliminate regulatory gaps; fourth, research the relevant risk-resolution mechanisms for new digital financial services; fifth, develop SupTech and enhance regulatory efficiency; and sixth, step up cross-agency and -border collaboration.

I. Basic definitions of financial stability

The study of the relationship between digital finance/fintech and financial stability should begin with how to define “financial stability”. For the Financial Stability Board (FSB), financial stability is the ability of the global financial system to withstand shocks and prevent the interruption of financial intermediaries and other financial system functions. Once these functions are interrupted, it will have a serious adverse impact on the real economy.

According to the European Central Bank (ECB), financial stability can be defined as a condition in which the financial system – which comprises financial intermediaries, markets and market infrastructures – is capable of withstanding shocks and the unraveling of financial imbalances. This mitigates the prospect of disruptions in the financial intermediation process that are severe enough to adversely impact real economic activity.

The People’s Bank of China defines financial stability in the China Financial Stability Report, 2005 as a condition in which the financial system is able to function effectively in all key aspects. Under such a condition, the macro economy operates soundly, monetary and fiscal policies remain prudent and effective, financial ecosystem continues to improve, financial institutions, market and infrastructure are able to fulfill their functions such as resources allocation, risk management and payment and settlement, and more importantly, the financial system is able to function smoothly while facing internal and external shocks.

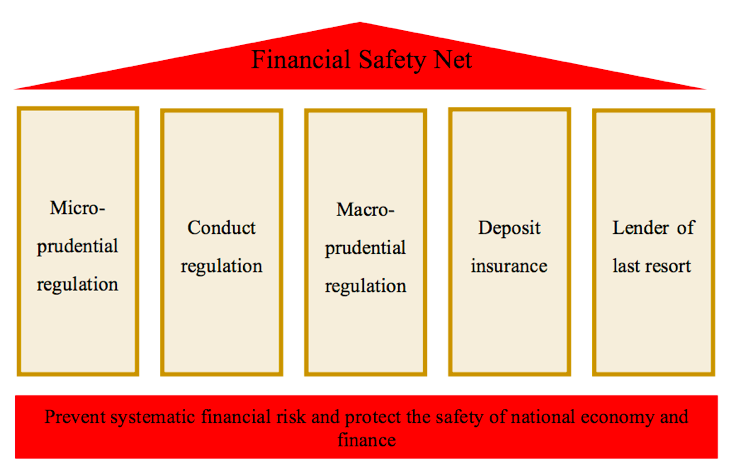

By the basic definitions of financial stability, digital finance/fintech is transforming the way of providing financial services and changing the landscape of financial industry, while new financial service providers are bound to influence financial stability on five dimensions of the financial safety net, including microprudential regulation, conduct regulation, macroprudential regulation, deposit insurance and lender of last resort.

II. Fintech advances to promote financial stability in the long term

1. Enhancing the financial system’s transparency

First, reduce information asymmetry and improve the capacity for risk assessment and pricing. For example, the big data technology can be applied to extract and analyze vast data, develop risk-specific financial tools, make risk assessment and pricing more accurate, and enhance the risk management capacity of all market participants. Second, raise the transparency of the social credit system. For instance, at financial institutions, introduction of deal trackers facilitates the due diligence process, saves compliance cost and helps them carry out the anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) requirements.

2. Enabling the financial system to gain efficiency

With the rapid advancement of fintech, the financial system becomes more ready to accept new technologies, improve services, change the business models, reduce operating costs and gain efficiency in allocating resources in the financial market. For example, a research report of the FSB notes that the Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) can shorten settlement time and improve the efficiency and speed of trade execution, thereby reducing counterparty risk exposure and freeing up collateral and capital, which in turn helps increase the efficiency of the overall financial system.

3. Boosting market competition

First, reduce market entry barriers and concentration. For example, big data analysis and the automation of loan disbursement can help eliminate access barriers to credit services, while robo-advice can lower investment barriers. Some legitimate new digital financial service providers act as alternatives to banks in a way, which can not only reduce the concentration of credit in the banking system, but also provide credit support in the event of a crisis in the banking system. Second, the use of technologies such as DLT help to reduce concentration in the settlement process.

4. Providing financial regulators with a toolbox

The rapid advancement of fintech has spurred the financial market’s “go-digital” drive and provided financial regulators with more tools. For instance, in terms of shareholder eligibility, identification of connected transactions and liquidity management, big data-based intelligence algorithms can realize real-time analysis of and response to risks by scanning financial, shareholding and related party information of an enterprise to draw a risk picture. The ECB has developed a tool based on network analysis and graphical visualization to help regulators gain insights into their targets’ private equity fund holdings and the relationships between important institutional shareholders.

5. Enhancing financial inclusion

The development of fintech can deepen and widen the penetration of the financial system and financial services, and facilitate the access of residents and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to financial services, thereby promoting sustainable economic growth and diversifying investment risks. Take the big data-based lending for example. It increases unsecured loans to SMEs.

III. Digital financial development to bring about new topics and challenges to financial regulation and lead to new characteristics in risks

1. Micro-financial risks possibly accompanying fintech advances

First, liquidity risk. For example, there may be maturity mismatch and currency mismatch in fund utilizations of digital financial services. The increased digitalization of finance in recent years has come with the taking of nationwide personal deposits by some local small banks or even village banks via third-party online platforms, marking a shift from reliance on local deposits to the whole country’s deposits. Deposits taken by some banks over online platforms (mostly non-local deposits) account for as much as 70% of their liabilities. They highlight deposit insurance and hint “risk-free and high-yield” during marketing campaigns in order to attract depositors with a high interest rate. Certain risky institutions have also obtained non-local deposits through Internet platforms.

Such deposits over Internet platforms are open-ended, and feature great interest rate sensitivity, an overriding share of non-local customers, low customer stickiness and early withdrawal options, and they are far less stable than offline deposits, making liquidity management harder for small- and medium-sized banks. In addition, the counting of Internet platform deposits wholly into personal deposits results in overestimation of liquidity match ratio (LMR), adequacy ratio of high-quality liquid assets (HQLAs) and core debt ratio.

(1) Overestimation of LMR. LMR = maturity weighted funding / maturity weighted assets. It is a measure of a bank’s maturity composition of major assets and liabilities and should not be lower than 100% based on the regulatory requirement. There are different coefficients for LMR based on the maturities of assets and liabilities (<3 months, 3 months to 1 year, 1 year or above). The longer the deposit term is, the higher the coefficient is (the coefficient for a maturity of 1 year or above is 1). Although Internet platform deposits have a relatively long maturity, the term choices are actually more flexible. Any calculation on the basis of the long maturity may overestimate LMR.

(2) Overestimation of HQLA adequacy ratio. HQLA adequacy ratio = HQLAs / short-term net cash outflows, which should not be less than 100% in line with the regulatory requirement. The denominator “short-term net cash outflows” refers to the possible cash outflows minus the cash inflows under stress scenarios. Among the possible cash outflows, the deposit run-off rate is only 8%, in sharp contrast to the highest interbank deposit run-off rate of 100%. The inclusion of all deposits on the Internet platforms in total deposits results in a low denominator of the HQLA adequacy ratio and thus inflates the indicator.

(3) Overestimation of core debt ratio. Core debt ratio = core debt/total debt, which should not fall under 60% according to the regulatory requirement. The numerator “core debt” includes the stable portion in demand deposits and the portion with a remaining maturity of more than 90 days in time deposits. 5-year resident savings on the Internet platforms are a kind of core debt, but they are not as stable as the local traditional 5-year residential savings, which will overestimate the coefficient.

So, these savings are more instable than local savings. Several of the bank runs in the world over recent years have changed from outlet-focused runs to online runs. During bank runs in the past, banks usually piled up large amount of banknotes on counters to show depositors “please rest assured. We have quite a lot of money.” Bank runs were usually over in 1-3 days, and the success of keeping less money away from counters meant putting risks under control. However, with reference to the recent international runs, defending counters just led to securing 10-30% of the deposit funds, and 70% of the deposit funds fled quickly. Against this background, how to tackle online runs becomes a new topic.

Second, credit risk of big data-based credit business. (1) Long tail customer risk. The UN Secretary-General’s Special Advocate for Inclusive Finance for Development (UNSGSA) mentioned in a report that the excessively fast growth of marketplace lending in some countries have led to over-indebtedness and rising delinquencies among relatively poor borrowers. This has emerged in previous years, but become more evident in the U.S. and some other countries in 2020 due to COVID-19. (2) Credit risk due to deficiencies of credit risk assessment models. Typically, the models have not been tested over a full credit cycle, with the data quality and completeness possibly inferior to traditional lending. Some models, relying too much on hard data while overlooking soft indicators, will weaken the assessment quality in the case of strong heterogeneity in risks.

Third, operational risk heightened by the digital business model. (1) Cyber incident risk, e.g. data leakage, fraud, business interruption, and cyber-attacks. In recent years, cyber incidents such as the Wannacry incident and the NotPetya incident have caused serious losses to the financial sector. (2) Internal governance and process control risk. For example, many new digital financial service providers lack standardized processes for data collection, storage and processing, leading to misuse of data. Some cryptoassets adopt decentralized and “public chain” design, with inadequate governance framework and process control, which makes it difficult to ensure operational security and robustness, and also increases AML/CFT risks. A survey found that about two-thirds of the world’s 120 most popular cryptoasset exchanges had failed to implement AML/CFT and know-your-customer (KYC) requirements. (3) Over-reliance on key third-party service providers. According to U.S. tech media TechCrunch, in early 2019, a trove of more than 24 million financial and banking documents, representing tens of thousands of loans and mortgages from some of the biggest banks in the U.S., has been found online after a security lapse of the server provided by OpticsML, a third-party company.

The above factors, together with the fact of leverage amplification by the joint lending of new financial service providers and commercial banks, may lead to insufficient, if not severely insufficient, capital requirements on these new financial service providers.

2. Systematic financial risks possibly caused by fintech advances

First, some emerging digital financial services will easily give rise to reputational contagion and add new contagion sources. For one, it is easy for retail business to spread reputational risk, in particular in the cryptoasset field. A large-scale run on a cryptoasset is very likely to cause panic in the market. Consequently, users may withdraw other similar assets as well. For two, fintech brings about new channels for the systematic risk to spread. The wider application of fintech will make it easier to produce complicated network effects and infections. For example, the conventional algorithmic trading may expose the entire financial market to unexpected systematic risk. In 2010, the Dow Jones Index of the U.S. plunged by 700 points in a half-hour roller coaster but then dramatically rebounded by 600 points. A major reason for the “flash crash” that temporarily ate USD1 trillion into the U.S. stock market was algorithmic flaws in automated trading.

Second, digital financial services feature more substantial procyclicality and volatility in many cases. For example, the online lending platform business may increase the procyclicality of the credit business for the reason that the online lending platform business is heavily influenced by the risk appetite of personal investors and the untested credit risk models may lead to underpricing or overpricing of risk, and less accurate credit quality assessment and lending standards than those of traditional institutions. The herd effect of robo-advice is also obvious. When the market is in stable operation, robo-advice can capture price movements via high-frequency data and acts as a more active matchmaker of transactions. Such procyclicality is also seen in the period of market liquidity strain, when robo-advice will quicken exits from the market and increase price nosedives.

Third, the increasing systemic importance of new digital financial service providers may increase the interruption risk of key services and cause market failures due to monopoly. On October 6, 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives issued a 449-page report on possible anti-competition and anti-trust behaviors of large technology firms, pointing out that tech-giants are competing unfairly in the market leveraging their monopolistic position and recommending stricter regulatory actions and even splitting. Subsequently, the U.S. Department of Justice officially sued against a technology company, accusing it of monopolizing the search field by illegal means.

Fourth, the widespread use of cryptoassets and digital currencies may increase cross-border arbitrage and intensify cross-border capital flows. On the one hand, cryptoassets are not restricted by geographic boundaries. Without international regulatory coordination, the regulatory rules of a country will not be effective in another. Due to cross-border differences in market sophistication, justice, regulation, currency convertibility, etc., things that are illegal in a country may be legal in others. Thus, cross-border regulatory and judicial cooperation and communication are costly. On the other hand, the use of digital currencies issued by major reserve currency issuing countries by residents of countries with high inflation rates and bigger exchange rate fluctuations may weaken the sovereign status of the latter countries’ currencies, bypass capital controls, and increase their capital flows and central bank’s balance sheet fluctuations. At the 2019 Bund Summit, I made three points about Libra: 1. we must strictly define that the legal tender of China is RMB, and all domestic transactions must be valued and settled in RMB. 2. We must deem Libra a foreign currency. Its launch in China must strictly abide by China’s prevailing foreign exchange administration regime. 3. Technically, we must differentiate in a digital setting which transactions occur between domestic entities and which occur between domestic and foreign entities. Libra must be strictly forbidden in China if the above three points cannot be realized.

3. Regulatory gaps remain for fintech

First, many institutions are unlicensed to carry out financial business. Such illegal financial activities include two types: First, financial activities in the name of technological innovation. Online lenders which thrived years ago offered petty loans and guarantees, among others, but they did not obtain any financial license and were out of the regulatory perimeter. Second, cross-border financial services disallowed in China. Some foreign institutions or Chinese market entities got foreign financial licenses by taking advantage of the characteristic “relaxed access at abroad and eased regulation at home”, and then they provided financial services to domestic customers on digital platforms for regulatory arbitrage, thereby disturbing China’s financial order. Similarly, the misconduct of getting petty loan license in a province of China and then launching national petty loan business over the Internet should also be deemed illegal because they are unlicensed in other provinces.

With respect to domestic and cross-border payment, banking, securities and insurance businesses, many new financial service providers have established companies and been granted financial licenses abroad, but they dare not carry out any relevant activities in the U.S., Australia, the UK and Japan. However, they dare to do so in China. This actually challenges Chinese regulation and Chinese justice, and we must counteract.

Second, lots of key third-party services provided by non-financial sectors still leave a blank in financial regulation. Financial institutions’ outsourcers which may not belong to traditional financial institutions are possibly regulated in a way weaker than financial institutions. Alongside the increasing scale-up of service provisions to financial institutions, these third parties may become a potential source of risk.

Third, how fast fintech updates and how intelligent it becomes makes regulation possibly outdated, including lagged regulatory capability and regulatory data gap, or even difficulty in ensuring the authenticity of basic data. Financial regulators are not technical experts, which, coupled with the limitation of regulatory resources, makes it hard for them to understand and assess fintech innovation and models. For example, some big data analytics models are relatively complex and lack interpretability. It is difficult for regulatory authorities to assess their technical robustness and predicate their effects on market conduct; as some black-box algorithms are not transparent enough, it is difficult to effectively audit their safety.

4. New challenges of higher financial digitalization to conduct regulation

First, at the retail end, consumer protection is becoming more complex and difficult. With the digital transformation of the financial industry, new technologies such as fingerprint payment, payment by face and remote account opening are emerging in a continuum. Personal identity information and financial information are being excessively collected and put into unauthorized use commercially or within a group. As a result, consumer infringers, methods of infringements and forms of infringement are diversifying. A typical example is that when a consumer’s mobile phone is stolen, he may suffer property loss, mental impairment or life threatening, e.g. information leakage, credit card theft, and identity theft for new loan application. Moreover, transactions and evidence in the digital environment are trending to be electronic, putting consumers in an obvious technical disadvantage because the generation, fixation, and retrieval of electronic evidence are mostly controlled by operators. At the most basic level, many consumers lack both financial knowledge and technological knowledge.

Second, at the wholesale end, issues such as market manipulation, insider trading, resource swap, cross-subsidy, conflicts of interest occur from time to time.

Third, it is more difficult to detect a misconduct taking advantage of technology. For example, the Latvian hacker Nagaicevs hacked into the online brokerage accounts of most securities firms in the U.S., carried out about 159 manipulations and gaining more than USD870,000 from manipulating 104 securities of the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq. His misconduct was so covert that it was not discovered and investigated by the U.S. Securities Exchange Commission until 14 months later.

5. Fintech possibly to weaken the efficiency of existing financial safety net

First, fintech advancement may exacerbate the trend of “decentralization” to an extent beyond the reach of the lender of last resort. The central bank’s lender of last resort mechanism, central to the financial safety net, mainly covers centralized financial institutions, typically commercial banks in China. This step-in is changing its coverage against the extensive application of the decentralization technology.

Second, in the private sector, digital currencies may reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy and the lender of last resort mechanism. The wide use of digital currencies in the private sector will inevitably lead to fragmentation in a country’s sovereign currency-denominated economic activities, leading to issues similar to “dollarization”, which will affect the central bank’s monetary policy transmission and the effectiveness of the lender of last resort mechanism.

IV. Improve the regulatory system, enforce strict market discipline and allow fintech to play a positive role in supporting the real economy and safeguarding financial stability

1. Work out the prudential regulation requirements to ensure full coverage of fintech business

First, strictly exercise licensing and crack down on “unlicensed activities”. Per Chinese laws in force, unlicensed operations are illegal financial activities. As the financial industry adopts rigorous licensing-before-entry and business regulation requirements, large technology firms should also follow the same requirements if they want to venture into the financial industry. Financial regulators in Singapore and Hong Kong, China have introduced new types of license, e.g. digital/virtual banking licenses. What’s more, regarding entry, some new financial service providers are continuously playing an active role in domestic and cross-border financial services without being licensed. Is this a reflection of financial repression? Or, does the failure to root out unlicensed activities and even see the rampant growth of such activities mirror the need to make regulation more efficient and timely? We need to reflect on what can be done to lower market entry barriers and enhance the competitiveness of the financial industry on the premise of risk prevention, and what must be done to enforce the law strictly in time, crack down on illegal activities and operations without licensing, and maintain market order through exercising serious regulation and justice.

Second, build a prudential regulation framework suiting to the characteristics of new digital financial service providers. The framework should include minimum capital requirements, liquidity risk regulatory requirements, market risk regulatory requirements, credit concentration requirements, connected transaction management requirements, leverage requirements, and operational risk management requirements. For example, to address the maturity mismatch risk that may arise from digital wallet business, regulatory authorities in some economies require digital wallets to deduct money directly from customers’ bank accounts or credit card accounts, and customer funds even if allowed for investment should be invested in highly liquid assets; China requires third-party payment institutions to deposit 100% of customer reserves with the central bank. There should be strict regulatory requirements on capital, leverage and single-account borrowing limit of the online lending business to avoid abuse of leverage, arbitrary enlargement of leverage and excessive credit granting, resulting in risk spillover to the banking system.

Third, novel digital financial business launched by traditional financial institutions alone or in cooperation with others shall be subject to heightened regulation and regulated in time, in addition to timely optimization of addition of prudential regulation indicators specific to its risk characteristics. As mentioned above, some commercial banks, especially small- and medium-sized banks, absorb deposits via the Internet financial platforms, getting rid of the spatial limitation of traditional channels. Judging by the fund sources, they have become national banks. Deposits on the Internet platforms are characterized by openness, strong sensitivity to interest rate, low customer stickiness, withdrawals at any time, and their stability are far less stable than offline ones, which have increased the risk hazards of small- and medium-sized banks. Or could the opposite conclusion be drawn? For this reason, regulatory authorities need to prudently anticipate the potential risks of Internet platform deposits and define the entry conditions and risk management requirements of these platforms’ deposit business. For example, only the commercial banks above a certain rating are permitted to engage in the deposit business on Internet platforms, the cap of platform deposits should be set based on the capital and risk status, and it should be made clear which small- and medium-sized banks are disallowed to carry out this business. Besides, the current regulatory rules give preferential treatments such as low cash loss rate and high stable funding coefficient to personal deposits. Will the inclusion of all the Internet platform deposits in personal deposits lead to overestimation of liquidity regulatory indicators, making it impossible to fully reveal the actual liquidity risk of banks? It is, therefore, important to revise the liquidity regulatory rules, improve the relevant monitoring indicators and strengthen the prudential regulation of Internet deposits. And, it is also important to study how to deal with the abuse of a coverage ceiling of RMB500,000 for a customer’s deposit and deposit interest rate competition (offering of high interest rates for taking more deposits). There is a need to strictly identify and regulate the provision of financial products and services by third-party platforms.

Fourth, demand new digital financial-service providers, who simultaneously provide different financial products and services, to set up an effective risk-isolation mechanism. Financial products and services have a clear boundary within the traditional framework and are separated by “firewalls”, while regulatory requirements are also well defined. However, as fintech develops, the boundary between certain financial products and services begins to blur. For example, certain Internet institutions integrate their “scenario + data + payment” resource advantages with bank-loan funds, and have developed the business model of “payment + microcredit + banks + securitisation”. Each business activity on its own requires a licence to operate, but once the activities are embedded the division of responsibility also becomes blurred. It then becomes difficult to get through the different business links, which in turn undermines the binding force of existing regulatory policies. The “financial supermarkets” of some Internet institutions also offer deposit and loan, insurance, funds and wealth management. Regardless of whether they are embedded services or one-stop financial services, regulators should ensure they observe the corresponding risk-isolation requirements.

Fifth, expand the scope of regulation to cover third-party technology providers, particularly institutions with significant systematic influence. The Bali Fintech Agenda released by the International Monetary Fund in 2018 states that, from a financial-stability perspective, the determination of important systematic institutions should be expanded to non-banking financial institutions and entities providing critical fintech infrastructure, and their regulation should be tightened. In reality, different regulatory requirements should be imposed on small and mid-sized technology providers, in addition to fintech service providers with systematic influence. For instance, regulators need to timely intervene in loan-procurement institutions that are taking part in credit creation, so as to prevent them from increasing the loan eligibility by manually adjusting the parameters of the risk-control model, leading to another subprime crisis.

I have previously given an example of trucks transporting hazardous goods, whose spillover effects are far greater than normal transporters in the event of an accident, so stringent requirements are imposed on them in every country. For example, the businesses concerned must register with the bureau for industry and commerce, obtain the administrative permit from the transport-management body and strictly abide by the regulations of related departments for the transport of hazardous goods, including the routes, time and speed. However, if a certain truck does not transport hazardous goods but constantly tailgates those that do, should the departments concerned also impose certain restrictions on it? If not, such truck may impact those carrying hazardous goods and indirectly lead to extreme spillover effects.

In other words, what must be regulated, must be regulated.

2. Develop a conduct-regulation system to maintain market order

After the subprime crisis in the U.S. in 2007, many countries stepped up conduct regulation to make up for inadequate financial regulation. The regulation of retailer conduct primarily protects consumers and investors and regulates conduct such as fraud, misleading, monopoly, unfair competition and improper debt collection, while the regulation of wholesaler conduct focuses on cracking down on market manipulation and insider trading. Objectively speaking, like the rest of the world, China attaches far less importance to conduct regulation than the prudential regulation of conventional financial institutions. Meanwhile, the country’s conduct regulation of new digital financial-service providers lags even far behind, which is one of the root causes of the never-ending financial chaos. Regulators mostly focus on reform, opening up, innovation, development and risk resolution after the collapse, and place little emphasis on progress and process regulation. The discussions lead to no decision, and a decision, if any, results in no action.

The development of a conduct-regulation system should focus on the following points: first is conduct regulation. The relationship with prudential regulation needs to be properly defined, with responsibilities clearly divided among central financial regulators and central-regional financial regulators. Activities-based regulation needs to be enforced, with particular focus on the management of non-financial businesses that illegally engage in financial activities, and regulators may not shift the responsibility onto one another. Second is the strengthening of the conduct-regulation capacity and the increase of the ratio of personnel with legal background. Third is the development of a tiered regulatory model, and regulation should focus on institutions with high market shares and high risk. Fourth is the establishment of a national call centre by regulators to advise consumers and help solving disputes. Emphasis needs to be placed on the building of a complaint database and data analysis, so complaints may actively serve as a “thermometer” and a “sensor” of the status of the execution of financial-regulatory policies. The importance attached to complaints and dispute resolution is a basic indicator of whether the regulators consider conduct regulation to be important and whether they are “people-oriented”. Fifth is striking a balance between the use and protection of personal information. The Personal Information Protection Law should be introduced as soon as possible to systematically protect the rights of financial consumers. The “data rights” of business operators must be recognised and protected through appropriate arrangements, as they legally obtain and use personal information while observing the principles absolute minimum and necessity, in order to promote the legal use of personal information. Sixth is to offer financial consumers appropriate affirmative protection and regulate the imbalance in technological application. Rules such as the extent and effect of the use of electronic proof need to be clarified, while the duty of business operators to save and provide evidence enforced. The reverse onus needs to be defined and the burden of proof of business operators reinforced. Seventh is to draw from the experience of other countries and devise a mechanism that offers handsome rewards to whistle-blowers, thus giving full play to the strength of the masses and the Internet. Eighth is to increase the severity of punishment for illegal activities.

3. Enforce the requirements of activities-based regulation and eliminate regulatory gaps

First is the application of the substance-over-form principle. Cross-industry and -market fintech products and services shall be centrally managed by specialised departments based on their business attributes and actual risks. Take the U.S. regulation of the marketplace lending industry for example, the granting of loans to clients using private funds require a loan permit from the state authority and must be regulated accordingly. The sales or issuance of bills to the public must be regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, while matters concerning consumer protection must be regulated by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Another example would be global stablecoin, which must satisfy the regulatory rules of different business areas, such as the launch of electronic money, collective investment schemes, taking deposits, securities trading and payment.

Second is technological neutrality, and no regulatory requirements may be relaxed as a result of different technological means. Regardless of the technological means and channels an institution adopts for business development, the focus should be placed on whether conduct such as the raising of public funds, public offering of securities or engagement in asset management is present, and access standards and regulatory requirements shall be imposed based on the actual business activities. For instance, for investment management such as robo-advisors, existing securities regulatory rules including registration, investor suitability and code of conduct shall be applicable, regardless of whether it adopts a traditional or a network-platform model. Another example would be business activities that rely on Internet technology, such as loans, insurance, funds, trusts and wealth management, shall all also being bound by the regulatory requirements imposed on similar business activities.

4. Research the relevant risk resolution mechanisms for new digital financial services

First is the establishment of a framework for business recovery and risk resolution, which includes: 1. The continuous upgrade of a cyber risk-response framework; introduction of cyber quantitative risk assessment; monitoring, identification and repair of key loopholes; and devising contingency plans for financial departments. 2. Devising recovery and resolution plans for key business; ensuring key digital financial-service providers may carry out liquidation or resolution in an orderly manner within the corresponding legal or bankruptcy framework; and ensuring key functions remain uninterrupted.

Second is the review of the effectiveness of the financial safety net against the background of decentralisation. Certain financial activities have been transferred out of the conventional banking system following the development of digital finance and fintech. Financial regulators need to re-examine the role of the key elements of the financial safety net, such as how the central bank may play its role as the lender of last resort, the coverage of deposit insurance, the systematic definition of fintech companies and crisis management and resolution mechanisms.

Clear signals should be sent out to the market, investors and consumers, as certain businesses are not even covered by the protective measures of the financial safety net.

5. Develop SupTech and enhance regulatory efficiency

The continuous development of fintech has furthered complicated the financial ecosystem and placed higher demands on the capacity of regulators, which must take full advantage of technology to enhance regulatory efficiency, accuracy and foresight. Fintech may arm financial regulators with new tools following the emergence of technologies such as big data, machine learning, natural-language processing and network analysis. In an investigative report on its members as released by the Financial Stability Board in October 2020, over one-third of the regulators have adopted SupTech, while the rest are going through a developmental or experimental phase. With the help of regulatory technology, financial regulation may achieve the following changes in the future:

First is improving the means of acquisition of regulatory data. Conventional regulatory-data collection means rely on data submitted by the regulated, whereby issues such as delay and false data may exist. With the help of fintech, the acquisition of regulatory data may be transformed from “submission” to “retrieval”. Supported by means such as an application-programming interface, financial institutions may connect their databases to the regulators, which may retrieve the data required at anytime, thus improving the timeliness and processing efficiency of regulatory data. For financial institutions, this simplifies the submission process, prevents repeated submission and alleviates the regulatory burden.

Meanwhile, the current obsession with collecting a massive amount of data must be rectified, as data analysis and mining are unable to keep up with it, leading to data being neglected. It is often after a major incident or risk has occurred before it is realised that the data in the system already reflect the risk.

Second is focusing on non-standardised and -structured data. Apart from standard structured data, regulators often are in possession of a large amount of non-structured data such as written reports, charts and network information. Previously, regulators had to rely on manual means to extract useful information, which results in low work efficiency and difficulty in fully using and monitoring the data. As technology such as natural-language processing develops, the extraction and use efficiency of non-structured data will be greatly improved, helping further diversify the data source of regulators. For example, currently regulators primarily use standardised data to identify bad shareholders and connected transactions, such as demanding financial institutions to submit information on the names, types, shareholding ratios and actual controllers of the top ten shareholders. The use of non-standardised data such as judgements, news and annual reports may be increased in the future, so as to reinforce “l(fā)ook-through supervision”.

Third is forward-looking risk monitoring. Conventional financial-risk monitoring often relies on financial institutions such as banks to submit data, which inevitably results in a certain delay. The application of regulatory technology may to a certain extent make up for the shortcoming. For instance, the European Central Bank employs machine learning to identify banking institutions that may face pressure in the future, based on their quarterly data and assisted by the overall data of the banking industry and the macroeconomic indices. Furthermore, the system may also identify key variables and indices in the model, thus helping regulators assess the risk scenarios in advance and providing them with adequate time for intervention.

Fourth is the achievement of real-time market regulation where possible. Illegal trading and suspicious transactions often involve a large number of accounts from multiple financial institutions, and the use of technology such as network analysis and machine learning may perform quick smart assessment on the legality of financial transactions with enormous sums. Illegal activities such as financial-market manipulation and insider trading may be monitored in real time, while market fraud and illegal sales may be effectively identified. Furthermore, clustering of suspicious trading parties and related financial institutions involving money laundering and terrorist financing may be timely discovered.

6. Step up cross-agency and -border collaboration

First is strengthening the collaboration between financial authorities and other government agencies. The development of fintech involves policy objectives such as competition, security, financial stability and consumer protection; consequently, coordination and collaboration should be stepped up between financial-management departments and other management departments responsible for data protection, market competition and consumer protection.

The G20 High-level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion carried at G20 Hangzhou Summit in 2016 stated that “positive communication mechanisms and channels must be developed for public and private departments in the development of digital finance”. Based on international experience, during the formulation of industry rules, leading businesses need to play a greater constructive role. Should the industry order be disrupted, not only are regulatory authorities accountable, the same goes for leading businesses.

Second is stepping up cross-border collaboration among global regulators. The digital world knows no boundary, and most fintech innovations are cross-border in nature. The inconsistent regulatory rules of each country for fintech will lead to regulatory arbitrage and gaps. Cross-border regulatory and judicial collaboration must therefore be stepped up, and the intensity of crackdowns on illegal cross-border fintech activities strengthened, so as to maintain financial order and stability in every country.