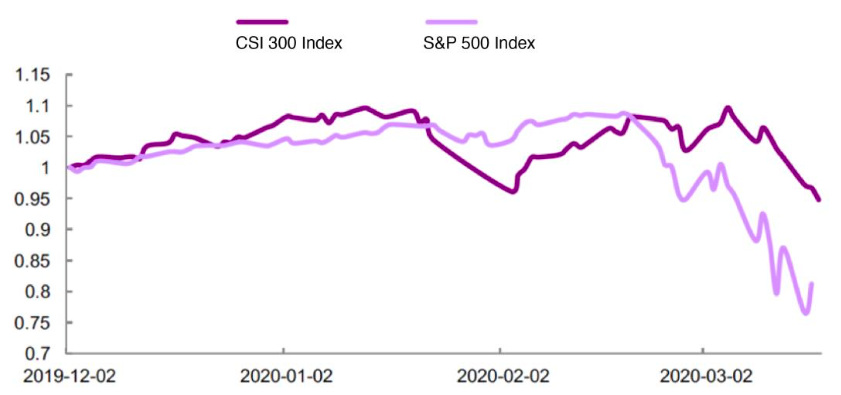

With the spread of the coronavirus globally, the recent turmoil in global financial markets, especially the sharp decline in the US stock market, has entailed concerns about a financial crisis similar to the one in 2008. In response, the US Federal Reserve relaxed its monetary policy significantly. Meanwhile, Chinese stocks slipped too, but by much less, showing greater resilience.

On the other hand, according to the statistics released by the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, China's economic growth plunged in the first two months of this year, with the momentum of the real economy under heavy downward pressure. This article discusses how to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on the global economy and markets based on current situations.

I. The two sides of "panic": pandemic control or market stability first?

The US market saw drastic fall and increased volatility within a very short period of time, which reflected panic among investors.

How to understand the panic? Under normal circumstances, panic among investors will cause herding effect, resulting in market slumps in a brief span of time, as seen during the financial crisis in 2008 and China's 2015 stock market crash. Usually the uncertainty about the future is a key factor in the exacerbation of economic downturns or financial crises. The goal of policy response is very clear, that is to reduce uncertainty and thereby anxiety.

However, the impact of pandemics such as infectious diseases is very different from that of economic or financial crises. Some panic is needed to bring the situation under control. Before vaccines and wonder drugs are developed, isolation is the only way to contain the pandemic. Instilling fears for the virus may be the key to effective isolation, or to say the best option governments have to gain widespread support for isolation measures.

In other words, public panic is needed for pandemic control at a certain stage, but does no good to financial markets and economic activities. This is an inherent contradiction.

Because of the this, governments often struggle with how to handle public anxiety when responding to pandemics. At the initial stage, they may decide to take their chances, and deliberately downplay the severity in order to avoid causing panic among the population.

Trump, the President of US, compared the coronavirus to the regular flu earlier on, emphasizing that the epidemic is controllable and has limited impact. He is now being accused of having bungled the chance of winning the battle. The British government has recently warned the possibility of a wide spread of the virus in the country, proposing the so-called "herd immunity" approach. In a public speech, the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that many families in Britain would lose their loved ones, which is deemed to be helpful for urging people to take the disease more seriously and isolate themselves.

The contradiction is reflected in the economic impact of the pandemic. After the Chinese government adopted stringent quarantine measures, the epidemic gradually showed signs of abatement. People saw the worst possible situation and became less anxious. This is conducive to stabilizing investor expectations, hence the market slump in China was relatively small. However, strict isolation measures almost lead to a sudden stop in economic activities.

The US failed to adopt strict quarantine and prevention measures in a timely manner, therefore it faces huge uncertainties as the epidemic spreads. People cannot see when the epidemic may peak. The resulting panic has hit the capital market hard, but the US real economy has been less affected.

Figure 1: Performance of A-share and US stock indexes

Source: Wind, Everbright Securities Research Institute

Note: The closing price was adjusted to 1 on December 1, 2019.

As the outbreak picks up pace and panic grows, the US has begun to ramp up its response and the public has also started to take it seriously, which will help contain the epidemic. However, there are still great uncertainties over whether these efforts are sufficient and whether social consensus for stricter control will only be reached when the epidemic spreads further. It should be said that they are moving in the right direction. People will become less anxious with stringent control measures in place, which will contribute to stabilizing expectations and the US financial market, while the impact on the real economy would begin to increase.

Looking ahead, after the drastic decline in the first quarter, will China's economic growth continue to weaken or rebound strongly as the epidemic ends? To what extent will the real economy in the US be influenced? Will the recent market turmoil bring on a financial crisis? Issues like these are crucial to the global economy.

The key is to properly understand the transmission mechanism by which the epidemic affects the economy. Two questions need to be answered – first, which does the epidemic affect more, the supply side or the demand side? second, is the pandemic a temporary problem or will it last long? These two issues are of prime significance for designing the macro policy response.

II. Supply shock or demand shock?On the supply (production) side, the major problem is that isolation measures prevent workers from going to work, that is, the effective labor supply would be greatly reduced for a period of time. In addition, blocked transportation would result in poor logistics and affect the provision of production and services. From the demand side, consumers would go out less, cutting the demand for services such as catering, tourism and entertainment, as well as the demand for retail goods.

Supply and demand shocks are very much interconnected. For instance, when people stop eating out while restaurant employees cannot go to work, there would be decrease in both demand and supply.

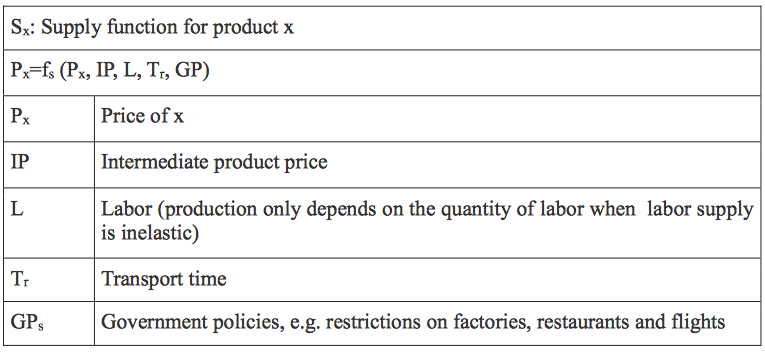

We can better learn the difference between quarantine measures and traditional influencers by studying the supply and demand functions.

Looking at the supply function of end products, the labor supply curve becomes a vertical line during the epidemic. Production depends on the quantity of labor instead of their wages, and the labor supply shrinks significantly. The transportation of logistics is prolonged or even interrupted; the government restricts or even shuts down productions that require gathering of people. The quantities of end products produced have decreased and the supply curve shifts to the left.

Looking at the demand function of the end products, in the short run, the epidemic may have little effect on the (long-term) wages of most people. However, consumer preferences would shift, with demand for purchases requiring contacts dropping and that for contactless shopping rising, which is also the outcome of prolonged logistic time. Governments' isolation measures will further hit the consumer demand that requires contacts. Although the contactless part of the economy could offset certain impact of the epidemic, the overall consumption demand would still decline.

So which is the principle contradiction, supply shock or demand shock? We need to find the influencers which drive the changes in production and demand.

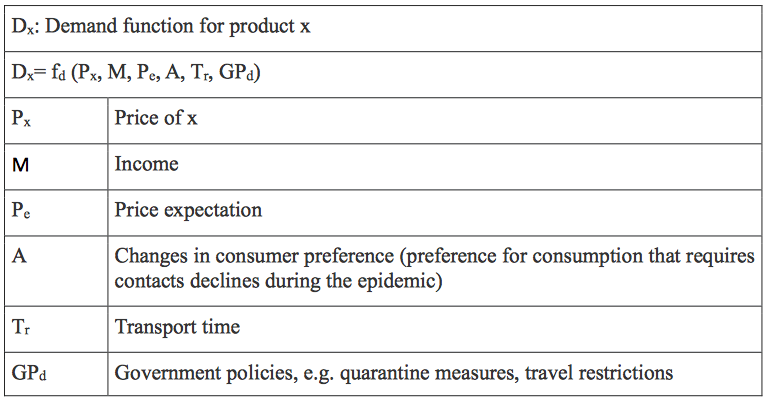

In the first two months this year, industrial value added (supply-side indicator) fell by 13.5% year-on-year (yoy), while investment (traditional demand-side indicator) fell by 24.5%. Seemingly, demand fell more than supply. However, if we dig deeper, what kind of demand shock could lead to such a plummet in investment? The answer can only be postponed resumption of work, and the resultant reduction in the supply of effective labor.

For example, infrastructure investment went down by 27% yoy, but funding was actually abundant. From January to February, the issuance of special bonds increased by 209% yoy, and the net financing of urban construction investment bonds increased by 26% yoy. The decline in infrastructure investment is mainly due to insufficient resumption of construction. Another example is the growth rate of online retail sales of physical goods, which decreased from about 20% to 3% from January to February, mainly a result of logistics restrictions in various regions and inadequate manpower in distribution and sales.

Whether supply shock or demand shock hit the economy harder will ultimately be reflected in price changes. Price is supposed to fall if demand decreases more than supply, and rise if supply decreases more than demand.

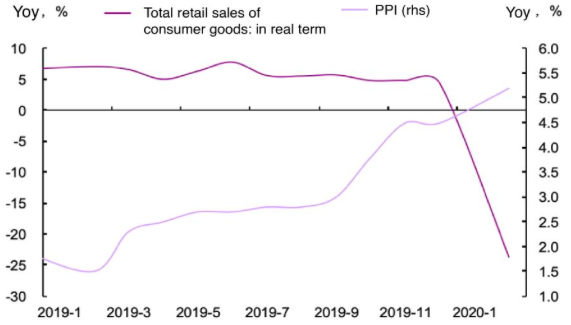

Based on data from the first two months, when the yoy growth rate of industrial value added went down from 5.9% in Q4 last year to -13%, the PPI growth rate went up from -1.2% to -0.2%, the yoy growth rate of total retail sales of consumer goods dropped from 7.7% in Q4 to -20.5%, meanwhile the CPI growth rate rose from 4.3% to 5.3%. If the reason why economic activities have fallen so sharply is insufficient demand, it is difficult to imagine that prices would rise instead.

Figure 2: Industrial value added and PPI

Source: Wind, Everbright Securities Research Institute;

Note: data in January and February are averaged to eliminate the effect of Spring Festival holidays

Figure 3: Real total retail sales and CPI

Source: Wind, Everbright Securities Research Institute

Note: data in January and February are averaged to eliminate the effect of Spring Festival holidays

The pandemic is likely to have greater impacts on demands in China than in Europe and the US. People out of fear for the coronavirus choose to stay at home and thus spend less. However, because Western countries have different economic and demographic structures from China, it is not likely that they will experience massive business shutdowns as a result of isolation measures.

The Chinese economy is labor-intensive, especially in manufacturing, which is why isolation has halted production activities. Besides, a large proportion of workers in China are rural migrants, who work in cities away from their hometowns. And because the epidemic attacked amid the Spring Festival, it has become very hard for them to get back to work on time. The situation in Western countries is quite another story—people usually live near, or at least, in the same city with their working place, so even if isolation measures are put in place, businesses are not likely to shut down because of restriction on cross-regional movement of people.

Of particular note, population density in the US is very low, and the impacts of isolation on people’s daily work and consumption activities are expected to be much lower than in China or Europe. As previously mentioned, the major challenge for the US is the capital market tumble as a result of market panic and fear of an impending financial crisis.

To sum up, the pandemic affects different countries differently. In China, the supply side has borne the brunt; in Europe and the US, demands are likely to be hit the hardest, with the latter also suffering additional financial turbulences. The financial system in the US is pillared by its capital market. The tumbling stock market has dragged consumer spending. And if a financial crisis really strikes, banks will rein in credit and investment will contract as a result, too.

Of course, the impact on supply vis-a-vis demand may shift as the outbreak progresses. If businesses remain shut for a long time, they will find it even harder to secure liquidity. Once they go bankrupt, there will be higher unemployment and permanent income losses, which will encumber consumption and investment demands. If that happens, the demand side will overtake the supply side to bear the more vicious blow.

Moreover, the pandemic's impacts on the US economy may not totally unfold until the second quarter, which means that China may experience more sluggish external demands in the second quarter or even over a longer period of time so that the domestic supply shock evolves into an external demand shock. It is obvious that the duration of the coronavirus outbreak matters, for China, Europe and the US alike.

III. The impact of the coronavirus on the real economy will likely stay after the peak of the pandemic

The development of the novel coronavirus outbreak goes through five stages: the first case gets confirmed, the number of newly-added confirmed cases peaks, the number of newly-cured cases peaks, zero newly-added confirmed case, and zero infection. Between the first and the second stages, many countries may experience a period of testing bottleneck. This trajectory has been seen in China (within and outside Hubei province), Japan and South Korea.

After effective isolation measures are put in place and the testing bottleneck is solved, the interval between confirming new cases and curing patients is relatively similar. Right now, the outbreak is already well under control in east Asia, including in China, and the focus of attention has turned to Europe and the US.

With mounting panic among the people, both Europe and the US have tightened isolation measures. On March 18 alone, the number of newly-confirmed cases in the US doubled those in previous days to 2932, which signals that the testing bottleneck in the country is gradually easing. With the White House releasing a guideline on fighting the epidemic, the isolation measures in the US are getting more effective.

According to the trajectory of the outbreak in other countries where the curve has been flattened, it is expected that the number of newly-confirmed cases in the US will peak right before March 25 (a week from March 18) and reduce to double digits two weeks after that, at around April 10, and the number of new recoveries will peak around April 15 (18-20 days from March 25).

The picture in Europe is more complicated, but countries are also strengthening isolations. Italy has locked down 11 towns on February 23, followed by Lombardy and 14 neighboring provinces on March 8. Two days later, a nationwide lockdown was imposed, which is set to be in place until April 3. Schools across Italy will also remain shut until that date, and all stores except food and drug sellers were asked to close down on the evening of March 11.

In general, although the speed and scope of the coronavirus's global spread are unexpected, it is unquestionable that strict isolation measures can effectively contain the virus. These measures are endogenous in the sense that the spread of COVID-19 will inevitably attract enough attention to induce countermeasures.

For major economies, the spread of the virus is very likely to be brought under control in the next few weeks, and the number of patients not cured yet will significantly drop in the second quarter of this year, too. Meanwhile, the impact of the coronavirus on the real economy will likely stay after the peak. However, the recent turmoil in the US financial market has triggered widespread concern over an impending financial crisis, which will have further impacts on the US economy and global economy as a whole.

IV. Is a financial crisis impending in the US?

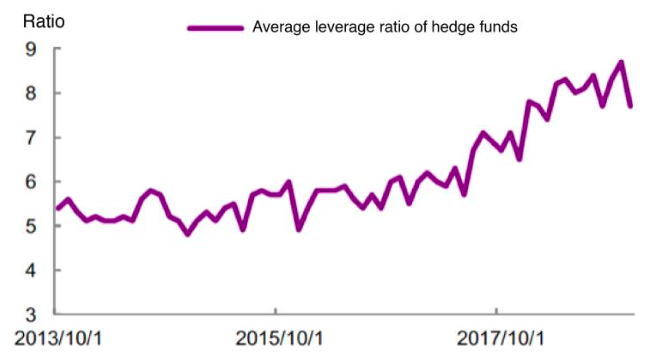

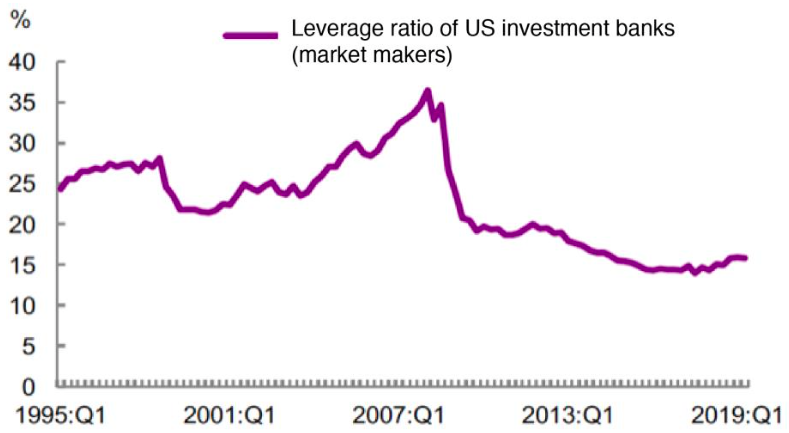

Triggered by widespread panic and technical factors, the US stocks have tumbled into a bear market, while credit spreads significantly widened, and transactions in the financial market got way more volatile. Getting a lot of attention is the role of hedge funds, whose average leverage ratio rose to about 8 in early 2019 from 5 back in 2015 (see Figure 4).

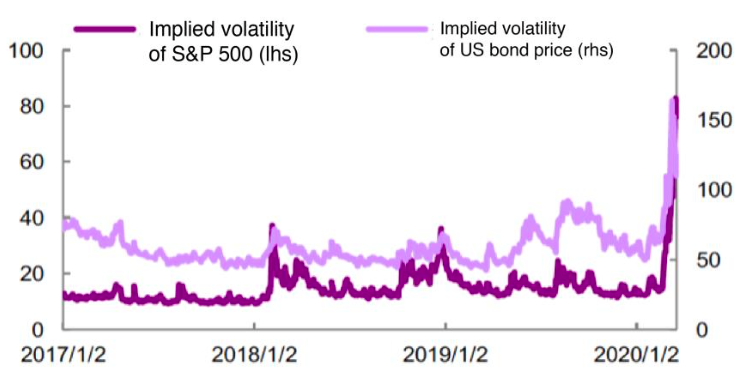

The risk parity strategy employed by some of the hedge funds focuses on controlling volatility—once volatility in the price of an asset exceeds a predetermined level, the hedge funds will have to reduce their holdings of the asset. Over the past two weeks, both the stock market and the bond market in the US saw surging volatilities (see Figure 5), forcing hedge funds to deleverage and causing a selling stampede; as hedge funds rush to undersell their assets, market fear intensifies and feeds back into further fluctuations in asset prices.

Figure 4: Average leverage ratio of hedge funds has significantly risen over the past few years

Sources: Fed; Everbright Securities

Figure 5: Volatilities in stock and bond prices in the US surged

Sources: Bloomberg; Everbright Securities

Besides, mutual funds have grown quickly in the past few years, and their holdings of corporate bonds have risen sharply. Fears over corporate defaults and rising credit risks triggered by an economic downturn have prompted some of the investors in mutual funds to withdraw their money, which placed greater downward stress on asset prices. However, mutual funds do not seem to be highly pressured by concentrated investor withdrawals, either, because according to statistics, several major ETF index funds were seeing net inflows during each US stock market meltdown recently.

Despite the mounting volatility in the financial market, we believe that the situation today is very different from back in 2008, and a systemic financial crisis is not very likely to strike in the US.

Although asset prices have tumbled and some businesses risk losing access to liquidity, the epidemic will not substantially affect the real economy as long as the banking system remains robust and works to prevent against systematic credit contractions.

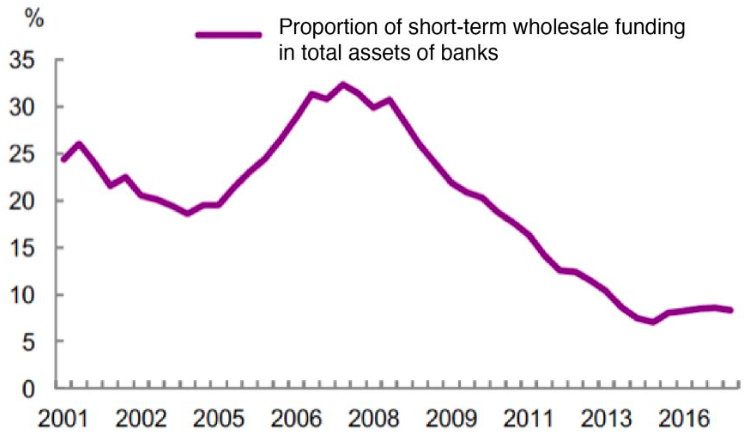

Over the past decade, the leverage ratio of the banking sector in the US has dropped significantly than in 2008, because the US government has enhanced regulations especially on banks ever since the subprime crisis. The financing risks faced by American banks is generally controllable right now—the proportion of liquid assets in total assets of systematically important banks has gone up to 16% from 5%, while that of short-term wholesale funding in total liabilities of these banks has dropped to 15% from 35% (see Figure 6), and the percentage of funding by deposits is nearing an all-time high.

As for the non-banking sectors, the leverage ratio of insurance companies has remained stable in general. To be specific, health insurance companies have seen a slight pickup in their leverage ratios to somewhere around historical average, while those of property and life insurance companies have continuously declined to an all-time low. Besides, the leverage ratio of investment banks, which dramatically added leverage before the subprime crisis, has decreased to below 20 from 30-40 previously (see Figure 7).

Figure 6: Proportion of short-term wholesale funding in banks' total assets fell

Sources: Fed; Everbright Securities

Figure 7: Leverage ratio of US investment banks significantly dropped

Sources: Fed; Everbright Securities

Although a systematic financial crisis seems unlikely, there remains the risk of economic recession brought about by the slide in American stock market. Past experience shows that stock market slump alone may not necessarily translate into a recession. However, it is widely believed that stock tumbles could take a huge bite out of household wealth and thereby dampen spending, because American families hold a considerable amount of assets in the form of stocks.

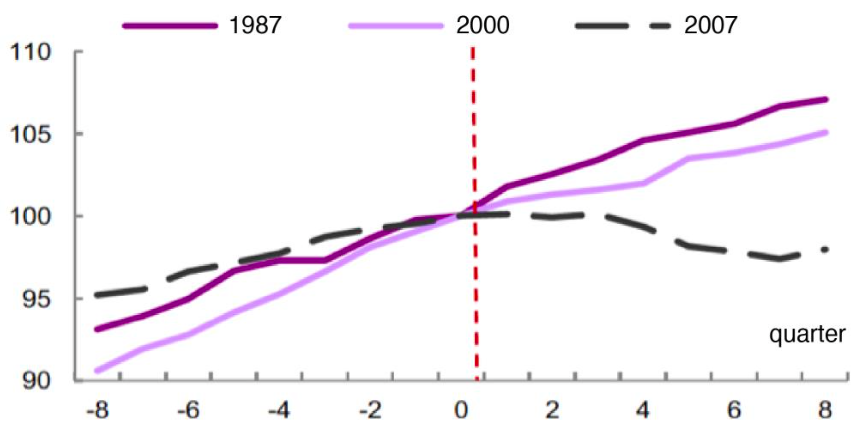

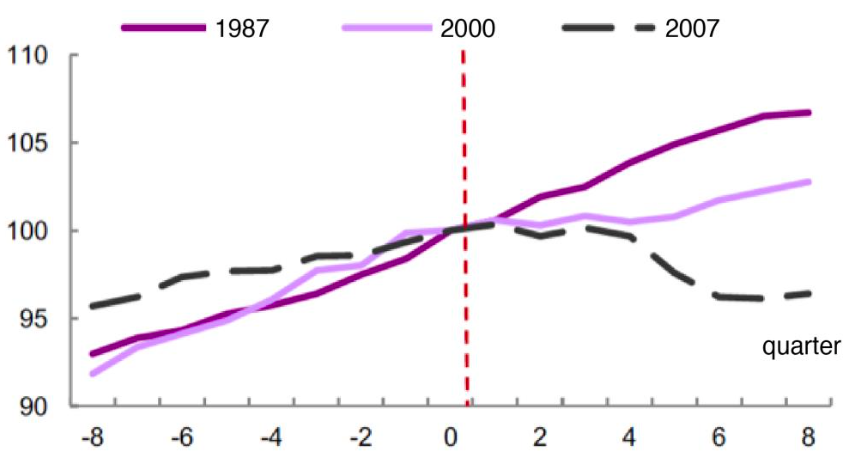

According to our study which compares three stock market crashes in the US since 1980 (the Black Monday in October, 1987, the burst of the internet bubble during 2000-01, and the subprime crisis during 2007-08), the crashes in 1987 and 2000 barely had any effect on consumer spending; the impact of the subprime crisis on consumption was bigger, but it was more a result of the burst of the real estate bubble (see Figure 8-9).

Figure 8: Actual consumer spending in the eight quarters before and after US stock market crashes

Sources: Wind; Everbright Securities

Figure 9: GDP in the eight quarters before and after US stock market crashes

Sources: Wind; Everbright Securities

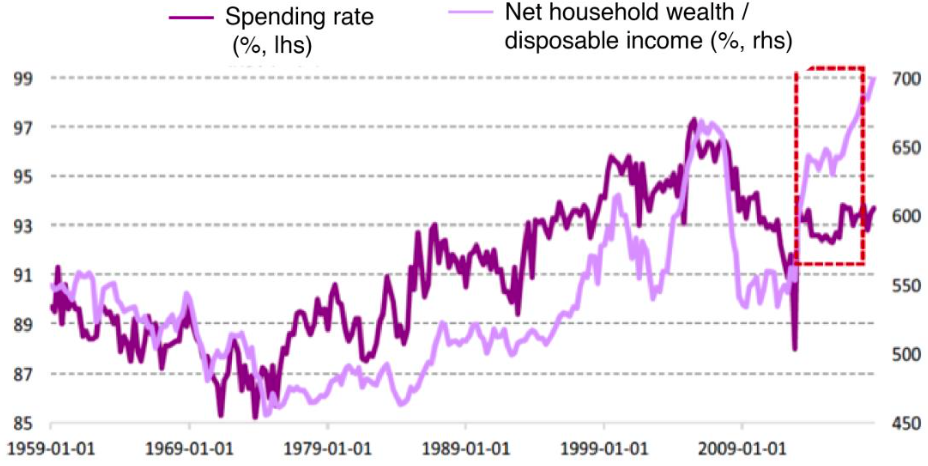

Compared with a decade ago, the wealth effect of the US stock market may have weakened. Despite a continuous boost in stocks after the subprime crisis and increased household wealth in the US, spending rate did not experience a remarkable rise. Our research shows that during 1975 - 2008, for one-dollar rise in stock wealth, household consumption picked up by an average of 0.027 dollars; and from 1975 to 2018, the average marginal propensity to consume out of one more dollar in stocks dropped to 0.018 dollars. In contrast, the average marginal effects brought by real estate wealth climbed up to 0.043 dollars from 0.032 dollars, which is to say, fluctuations in house prices have a much greater impact on consumption than those in stock prices.

Figure 10: Household wealth effects seem to be weakening after the subprime crisis

Sources: Fed; Everbright Securities

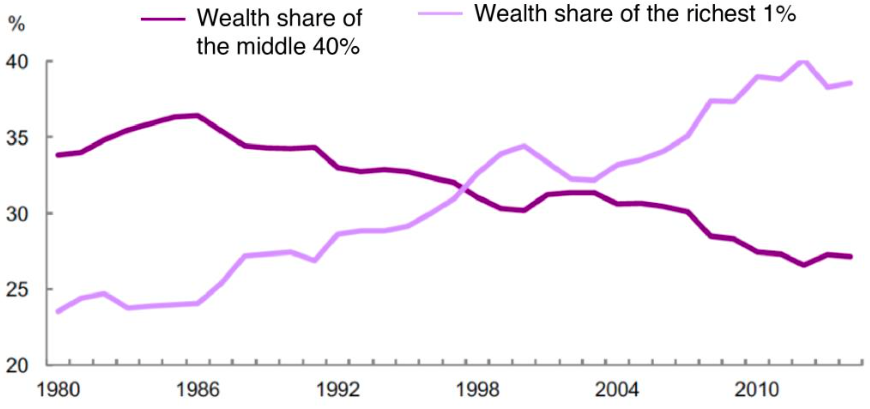

One of the reasons for the decline of stocks' wealth effect is the increasing polarization between the rich and the poor in the US—it is the rich, not the middle- and low-income groups, who have benefitted from the rise of stocks. In 2014, the wealth of the richest 1% in the US rose to 39% of the country's total wealth, the highest level since the 1930s. The share of wealth of the middle 40% has continued to decline, suggesting that the middle class is shrinking. Therefore, the impact of stock decline is more obvious on the wealth of the rich, who have lower marginal propensity to consume, and the impact on middle- and low-income class may not be so great.

Figure 11: Wealth inequality is high in the US

Source: Everbright Securities Research Institute, Federal Reserve

Although a stock market disaster itself does not bring about economic recession, when superimposed to the impact of the epidemic, it has increased the possibility of a technical economic recession in the US. In order to control the spread of the virus, many countries have taken measures to close borders, schools and cancel gatherings, and some firms have chosen to shut down and suspend economic activities. The rise of public panic and the resulting social distancing further increase the impact on the real economy.

In the short run, it is difficult for the US economy to avoid a negative growth for 1-2 quarters, and the decline may be quite large. But when the epidemic is over, economic activity will recover, and some consumer spending and business investment will be made up.

After the US stock market plunged, the Federal Reserve took several measures, such as slashing its benchmark interest rate and expanding the scope of asset purchases to help mitigate liquidity crunch and credit risks. On March 17-18, the Fed announced a series of "rescue" measures, including the establishment of the Commercial Paper Financing Facility (CPFF), the Primary Dealers Credit Facility (PDCF), and the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF). CPFF mainly aims to alleviate the financing pressure of commercial paper issuers, PDCF mainly targets primary dealers to encourage them to buy securities from the secondary market, and MMLF is used to help monetary funds and mutual funds cope with concentrated redemption. Without the Fed's measures, the impact of panic on financial markets may be greater.

Of course, whether the liquidity provided by the Federal Reserve can be effectively transmitted to the institutions or enterprises that need liquidity most is a question. Structural policy measures, such as the Fed's resumption of commercial paper financing, are needed, but fiscal policy support is even more needed. It is expected that the US government will help affected businesses and residents through fiscal expansion measures such as tax cuts and increasing transfer payments. International financial institutions such as the IMF are calling on governments to increase fiscal expansion, highlighting the importance of fiscal policy in dealing with the impact of the pandemic.

V. Macro policy response should be orientated towards public well-being

Based on the above analysis, following the sharp decline in economic growth in the first quarter, the second quarter may face new downward pressure due to the global spread of the pandemic.

To ease such pressure on the economy, people may naturally think of counter-cyclical adjustment, and the typical policy response is monetary policy relaxation and fiscal expansion, such as launching a new round of large-scale infrastructure investments, reducing the benchmark interest rate, or stimulating the real estate sector, as some have proposed. These are typical demand management measures, but the impact of the epidemic on the economy is different from the conventional downturn in an economic or financial cycle.

First of all, the epidemic is mainly a supply-side shock; although demand-side shock are mainly shown in Europe and the US, it is not a typical demand-side shock caused by income decline, rising interest rates, etc. Supply and demand shocks generated by the epidemic are due to "physical constraints" that reduce producers and consumers’ capabilities. In this case, the role of monetary policy in stimulating demand is limited—money is neutral, while supply creates demand so the supply side is the main contradiction.

Second, the impact of the coronavirus outbreak is short-lived. The more intense the panic, the more stringent the social isolation, the greater the impact on the economy; but at the same time the faster the epidemic will be brought under control. That is to say, greater impact of the virus on the economy is associated with shorter duration of its impact. Although the global spread of the pandemic makes the problem more complicated, the mechanism and logic of how it impacts the economy are the same. In a panic atmosphere, people tend to focus only on the present and have excessively pessimist medium-term views. If policy response is based on this, it will be an overreaction in hindsight, exacerbating the medium- and long-term imbalances.

Thirdly, the impact of the epidemic is borne by the real economy, its shock on the financial system is merely a by-product, which is fundamentally different from the 2008 or other financial crises. The epidemic hits the real economy and increases the nonperforming loans of the banking system, but as long as there is no financial crisis, the impact of credit contraction on the real economy will not be too large. The focus of policy response should be to support the real economy rather than the financial sector, or that the financial sector should support the real economy.

The above attributes of COVID-19's economic impact determine that the policy measures should be different from those employed to address conventional economic downturns or financial crises. Currently the policies should: first, be geared towards supporting supply and promoting supply recovery, rather than stimulating aggregate demand; second, be oriented towards public well-being, focusing on helping SMEs and middle- and low-income groups hit by the epidemic; third, provide targeted support to sectors of the real economy, pay attention to structural problems, and avoid medium- and long-term imbalances.

Fundamentally speaking, in addition to the traditional counter-cyclical measures, policy response should also have a humanistic perspective. Local governments should vigorously support firms to expand production of and shift production to medical supplies. Although a certain degree of overcapacity is inevitable when the epidemic fades, increased production capacity is in the benefit of anti-epidemic efforts and people's lives and health.

From a humanistic perspective, an orientation towards public welling-being means that the contradiction between epidemic prevention and work resumption can be reconciled. Containing the spread of the virus is the priority, and it is necessary and reasonable to take strict prevention and control measures, especially considering that the impact of these measures on the economy is short-lived, and can be removed after the epidemic subsides.

In this sense, there is no trade-off between controlling the epidemic and ensuring economic growth. Efforts to safeguard the economy should prioritize industries closely related to people's livelihood. As the epidemic comes to an end, work resumption will gradually expand until economic activities fully return to normal.

A people-oriented approach also involves how to interpret supporting the supply side. On the one hand, we should create favorable conditions to promote the resumption of work and production; on the other hand, we should provide support to firms and workers during the shutdown period, which requires the government to make economic sacrifice such as reducing taxes and fees, and leverage the role of policy-based finance.

Although production have stopped, but wages, rents and other expenditures will continue to occur; without external financial support, SMEs will face capital chain rupture. Once bankruptcy happens, firms will not be able to be revived even when the epidemic is over. In such a special period, banks should not draw loans, policy-based finance institutions should provide low-interest or even interest-free loans which essentially is a fiscal measure.

It is neither reasonable nor realistic to initiate a new round of large-scale infrastructure investments due to the following reasons:

First, the impact of the epidemic on supply has reduced physical resources, and large-scale infrastructure investment means that the public sector will occupy the already declining resources.

Second, the epidemic's impact on the economy is short-term, while infrastructure projects generally take several years to complete, which indicates that there will be a mismatch between the supply and demand for resources in the next few years.

Third, if infrastructure financing goes back to the old path, in which local governments have to resort to "land finance" to secure financing without a substantial increase in fiscal deficit and special purpose bonds, it will bond credit with real estate again, and in turn foster financial pro-cyclicality which will further aggravate economic distortions and imbalances.

Although a new round of large-scale infrastructure construction is unrealistic, the epidemic has prompted a structural approach for filling in infrastructure gaps in public health and environmental protection. The potential of the so-called "zero-contact" economy unleashed during the epidemic will guide the public and private sectors to increase investment in new infrastructure projects such as 5G, big data centers and Internet of Things, which will promote industrial upgrading and improve supply efficiency.

Another market concern is whether the benchmark deposit rate should be reduced. There are three reasons for prudence in terms of cutting the rate:

First, the economic impact of the epidemic will be a net supply shock, which means that the natural interest rate that balances supply and demand will be rising, at least not falling.

Second, the financial sector should make some sacrifice to support the real economy. The net interest margin of banks in the fourth quarter of 2019 was 2.2%, relatively higher compared with historical levels. Financial institutions should tide over the difficulties with the real economy in such a special period. If both loan and deposit interest rates decline, the business sector would be benefited at the cost of the household sector.

Moreover, the adjustment of benchmark deposit interest rates has important implications for the income distribution of the middle- and low-income groups, who invest their savings mainly in bank deposits rather than risk assets. Lowering benchmark deposit rates will be a detriment to middle- and low-income individuals.

In short, policy response to the epidemic should be public well-being-oriented and phased. It should not exacerbate medium- and long-term macroeconomic imbalances. In particular, although the real estate bubble and the high leverage in non-governmental sector have eased to some extent, the problems are still prominent. Policy response should avoid large-scale stimulus on the demand side or on the real estate sector.