Abstract: In this article, the author analyzes how China's macroeconomic situation and policy response have evolved since the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, and discusses the importance of GDP growth target from three perspectives. First, without an growth target, many important indicators cannot be determined. Setting a growth target can help coordinate macroeconomic policies across government departments and levels and form market expectations. The 2020 Government Work Report actually has an implied nominal GDP growth rate of 5.4%. Second, ensuring employment, which has been identified as the top priority in the Report, does not conflict with economic growth. In fact, unemployment can only be resolved through two channels: economic growth and improved unemployment insurance system. Third, in the second half of 2020, China may face the dilemma of adopting more aggressive expansionary fiscal policy to buttress growth, which could lead to fiscal deterioration, and allow further growth slowdown to alleviate fiscal pressure. The former is the "lesser of two evils" as poor growth will eventually lead to a debt-deflation cycle.

I. Three phases of the Chinese economy since the end of 2019

China's economy encountered unprecedented shock from COVID-19 since the lockdown of Wuhan on January 23, 2020, and began to recover when the lockdown was lifted on April 12, 2020. Reviewing the course of China's economic growth since the end of last year and the government's policy adjustments over the past six months can help us better understand the 2020 Government Work Report and formulate policy suggestions.

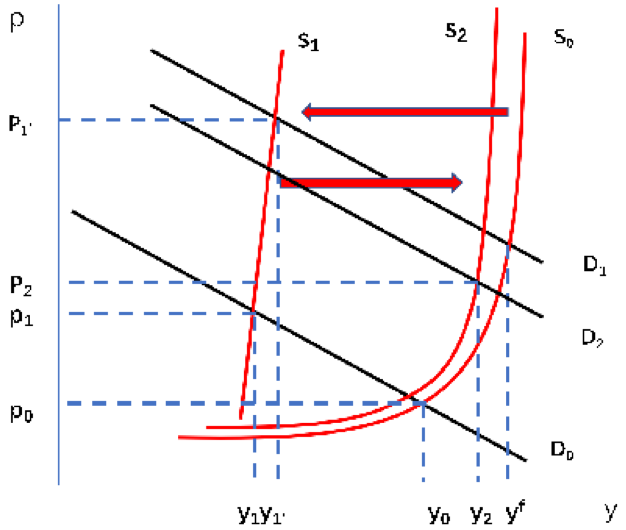

For this purpose, we first need a macroeconomic framework (Figure 1) based on changes of aggregate supply and demand to analyze the periodic characteristics of China's economic growth and macroeconomic policies since the fourth quarter of 2019. China's economy can be roughly divided into three phases since the end of 2019.

Figure 1: Aggregate demand and supply

The first phase is the period before the outbreak. The question heatedly debated then was whether China should maintain a 6% growth. Some scholars argued that China's potential growth rate was higher than 6% and China should not allow its growth to continue to decline. In the aggregate supply and demand model, assuming that China's potential output is yf, the actual output determined by the intersection of the aggregate demand curve D0 and the aggregate supply curve S0 is y0. The shortfall in effective demand is yf-y0. Therefore, the aggregate demand curve D0 should be shifted upward to D1 through expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, so that the actual output could equal the potential output.

The second phase is the anti-epidemic period starting with the lockdown of Wuhan. The main characteristic of this phase is supply shock, reflected by the leftward shift of the aggregate supply curve S1 which became almost vertical due to a sharp decrease in price elasticity. This means that no matter how much the price increases, output remains unchanged because of the disruption of the supply chains and production. At this point, the output dropped to y1, and the price level rose to p1. To simplify the analysis, we assume the aggregate demand curve to be D0. In fact, the demand shock was also severe, but secondary to and largely a result of the supply shock. At this stage, government's policy was aimed at getting S1 back to S0 without causing permanent damages (e.g. business failures). However, even with expansionary macroeconomic policies, the level of output was unlikely to see significant increase. That is to say, even if the aggregate demand curve D0 was shifted to D1, output would only gain a little increase (y1'-y1).

In the third phase, the epidemic was basically brought under control and the economy began to recover. At this stage, the aggregate supply curve began to shift to the right, while its shape returned more or less to the pre-outbreak one. During the epidemic, some enterprises were closed down, while some others became unable to adapt to new market environment due to structural changes and would never have new orders. The aggregate supply curve at this stage is S2. In response to the new supply curve, the government took expansionary policies which drove aggregate demand up to D2. We assume that the level of output corresponding to the intersection of S2 and D2 is the new potential output y2. It should be noted that the level of potential output may be lower than the pre-outbreak one because of the impact of the COVID-19. But it should also be emphasized that although D2 is below D1, D2 may be supported by more expansionary policies as the endogenous part of aggregate demand (e.g. lower income expectation led to decreased consumer demand) was reduced due to the impact of COVID-19 outbreak.

In short, during the epidemic, the goal of China's economic policy was to try its best to preserve production capacity, keep businesses from going bankrupt, and enable workers to return to work as soon as possible. If many workers got infected and lost ability to work and a large number of factories were closed, the country’s potential supply capacity would be permanently damaged. During this period, the government took a series of measures to preserve supply capacity, so that the aggregate supply curve could return to S0 once the epidemic is over. The Chinese government did achieve this goal during this stage.

Now that the epidemic has been put under control (hopefully there will be no resurgence), the goal of macroeconomic policy has shifted from fighting the outbreak and providing relief to using expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to restore economic growth to its potential level.

II. Implied growth target for 2020 and the possibility to achieve it

Now that the goal of economic policy has shifted to restoring growth, the first question should be: What is China's GDP growth target in 2020? Unfortunately, the Government Work Report did not provide a direct answer.

Many economists argue that to ensure the quality of economic growth, China should not set a GDP growth target. But the speed and quality of GDP growth are not mutually exclusive. The real problem is not speed or quality, but how to measure GDP correctly. If a product is defective, it should not be counted in GDP; and if a product can cause pollution, it should be recorded as a negative value. When measuring GDP, the quality of goods is already taken into account, so the key to improving the quality of GDP is not to reduce GDP growth, but to measure it correctly. The quality of GDP is related to factors like market efficiency and government regulation. In any case, not setting a GDP growth target does not necessarily improve the "quality" of GDP, nor does a GDP growth target necessarily reduce the "quality" of GDP.

In my view, setting a GDP growth target, though not mandatory, is a requirement of implementing macroeconomic adjustment. Even governments in the most market-oriented economies would make annual growth forecast, not to mention a country like China. GDP (or GDP growth rate) is the denominator in almost all important economic indicators. Without an economic growth target, it would be difficult to determine many important economic and financial indicators and policies cannot be coordinated.

Does China really have no growth target? No. He Lifeng, head of the National Development and Reform Commission, mentioned in a speech that the key elements of a growth target have already been embedded in relevant indicators and policies, including fiscal, monetary and other policies. For instance, the deficit of 3.76 trillion yuan and the deficit ratio of 3.6% were presented in the 2020 Government Work Report. It can be easily seen that the nominal GDP growth rate implied in the two figures is 5.4%. In fact, it would be impossible to create a fiscal budget without a GDP target, not to mention developing fiscal policy.

The same is true for monetary policy. Without a growth target, the targets for intermediate indicators such as the growth of M2 and credit can hardly be set. Some countries, especially developed countries, implement an "inflation targeting" monetary policy regime with inflation rate as the sole target, which differs from China's approach.

In a recent remark, Yi Gang, governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), said that the central bank will keep liquidity at reasonably ample levels in the second half of this year, which is expected to lead to an increase in RMB loans and social financing by 20 trillion yuan and 30 trillion yuan, respectively. I believe he certainly had inflation and GDP growth forecasts in mind when making this remark. Otherwise, how could he estimate the total amount of RMB loans and social financing for the whole year?

So what we need to talk about now is not why government does not set a growth target, but why it doesn't announce the target explicitly. A number of economists have answered this question. Some of the more prevalent interpretations include: the impact of the COVID-19 is highly uncertain, and neither setting the target high nor low would be good; it's better not to set a target as achieving positive growth won't be uneasy; if the target rate proves to be too high, strong stimulus measures must be adopted, thus using up valuable policy space prematurely; China needs to focus on increasing domestic demand, ensuring 'six priorities' and stability in six areas; without a growth target, efforts could be diverted to improving the quality of growth and so on. But none of these reasons can provide a logical explanation for not setting a growth target for 2020.

From a macroeconomic management perspective, if the government has a GDP growth target, it should announce it publicly. The benefits of doing so include better coordination of policies among various government departments, and more efficient communication with the market. Isn't effective communication with the market something that has been strongly emphasized by Chinese economists in recent years? Only through efficient communication can market react to policies accordingly. Besides, releasing the growth target can help improve inter-agency coordination and enhance public supervision of the government. In other words, sending a clear message can create synergy within the government and help the market form appropriate expectations. Without an open, clear and unified growth target, it would be difficult to coordinate policies across various functional agencies and government levels. But admittedly, there are some reasons not to announce the growth target, some of which are beyond the scope of economics.

So what is the growth target for 2020 which has been integrated in other economic indicators? From the officially announced fiscal deficit and deficit ratio, we know that the target for nominal GDP growth in 2020 is 5.4%, which is pretty clear. But what about the real growth target? We don't know about the official GDP deflator in 2020. Based on historical trends, GDP deflator can be set to rise by 2% in 2020, indicating that government's unannounced target for real GDP growth in 2020 should be 3.4%. If the deflationary trend further develops in the second half of 2020, the real GDP growth target should be even higher.

In April, we projected a real GDP growth of 3.2% in 2020. An important premise for this conclusion was that China's economy could return to the normal growth rate of 6% in the second quarter. But based on economic data for January-May, the market consensus was that real GDP growth in the second quarter should be around 3% year on year (yoy), or 1% from a more pessimistic perspective. Using these two figures as the lower and upper limits, and assuming that yoy growth of effective demand in the third and fourth quarters of 2020 could reach 6%, the same as the potential economic growth rate, the real GDP growth rate in 2020 should be between 2% and 2.4%. Assuming a 1% inflation rate in 2020, nominal GDP growth should be between 3% and 3.4%. As economic recovery was weaker than expected in the second quarter, it would be difficult to achieve the nominal GDP growth target of 5.4% implied in the current budget for 2020. So, can China's nominal GDP growth reach 3.4% in 2020? What would be the necessary conditions to achieve this target?

GDP growth depends not only on the potential growth rate, but also on effective demand. To determine whether real and nominal GDP growth rates can reach 2.4% and 3.4%, respectively in 2020, constraints on demand should be analyzed in additional to constraints on supply. Due to limited data, our analysis has to rely on many assumptions, so the results are rough estimates at best.

Based on data from January to May and general economic principles, we can make the following assumptions. First, China's consumption growth in 2020 is roughly equal to GDP growth rate; second, the contribution of net exports to GDP growth is zero; third, the yoy growth rate of fixed asset investment in the second quarter is zero (out of negative territory). With consumption, capital formation and net exports accounting for 55%, 43% and 1% of GDP, respectively, and based on the above assumptions, consumption and net exports should contribute 1.87% to GDP growth in 2020. Thus, to achieve a nominal GDP growth of 3.4%, capital formation should contribute 1.53 percentage points, which implies a capital formation growth rate of 3.56% in 2020. Due to lack of data, the following analysis replaces capital formation with fixed asset investment [see endnote 2].

Fixed capital investment in the four quarters of 2019 were 10.17 trillion yuan, 19.72 trillion yuan, 16.21 trillion yuan and 9.03 trillion yuan, respectively, 55.15 trillion yuan in total for the year [see endnote 3]. China's fixed asset investment in the first quarter of 2020 was 8.41 trillion yuan. From January to May, fixed asset investment nationwide was 19.91 trillion yuan, down 6.3% yoy. In May, national fixed asset investment began to turn positive. Assuming that total fixed asset investment in the second quarter is equal to that in the same period of 2019, it can be calculated that to achieve an annual growth rate of 3.56%, the growth of the country's fixed asset investment in the second half of 2020 should reach 14.8%. Historical experience suggests that it is difficult to achieve such an increase though not impossible.

Further analysis shows that to achieve such a growth rate of fixed assets investment, the growth rate of infrastructure investment must be significantly higher. In the first quarter of 2020, the growth rates of investments in real estate, manufacturing and infrastructure, three of the four major components of fixed asset investment, were -7.7%, -25.2% and -16.36%, respectively; from January to May, the cumulative growth rates were -0.3%, -14.8% [see endnote 4], and -6.3% [see endnote 5], respectively; and in May, the yoy growth rates were 8.1% [see endnote 6], 5.2% and 10.9% [see endnote 7], respectively. At the end of the first quarter, the shares of these three components in total fixed asset investment were 24%, 26%, and 25%, respectively.

The yoy growth of real estate investment turned positive in March. Real estate investments in the whole year of 2019, the second quarter of 2019, the first half of 2019, the second half of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020 were 13.21 trillion yuan, 3.78 trillion yuan, 6.16 trillion yuan, 7.05 trillion yuan, and 2.1978 trillion yuan, respectively. Assuming that real estate investment would grow by 5% for the full year in 2020,it can be calculated that growth in the second half of 2020 should be 11.8%. Because real estate investment accounted for 24% of fixed asset investment in the first quarter of 2020, it could contribute 2.8 percentage points to the growth of fixed asset investment in the second half of 2020. That leaves the 14.5 percentage points (of growth of fixed asset investment in the second half of this year) to manufacturing and infrastructure investments as well as other investments.

We can make a simple (and very optimistic) assumption that manufacturing will grow by 10% in the second half of 2020. To simplify the analysis, we assume that "other investments" would also grow by 10% during that period. Thus, these two types of investments could contribute 5 percentage points to the growth of fixed-asset investment, indicating that the remaining 9.5 percentage points growth could only come from infrastructure investment. In this case, infrastructure investment must grow by 28%.

Obviously, it is difficult to achieve such a growth rate under the current conditions, not only because infrastructure investment requires a large amount of funds, but also because it involves other issues such as project pipelines, investor capability and incentive mechanisms. In practice, the growth of manufacturing investment is unlikely to reach 10% in the second half of 2020, suggesting a much higher growth rate of infrastructure investment is needed. It can be easily seen that it is extremely difficult to reach the 3.4% growth target of nominal GDP, not to mention the implied nominal growth target of 5.4%.

To sum up, the following conclusions could be drawn based on the above simulation:

First, assuming that real GDP growth in the second quarter is between 1% and 3%, and that from the third quarter, the trajectory of economic activities becomes consistent with that of potential economic growth, it is estimated that the growth of real GDP in 2020 should be between 2% and 2.4%, while that of nominal GDP between 3% and 3.4%.

Second, due to demand constraints, it would be very difficult to achieve a real GDP growth of 2%-2.4% and a nominal one of 3%-3.4% in 2020. In the absence of consumption and external demand as the main drivers of GDP growth (when the growths of the two outpace GDP growth), fixed asset investment must maintain a fairly high rate of growth, which can only rely on a higher growth of infrastructure investment.

It needs to be emphasized again that due to the lack of reliability and comparability of data and excessive assumptions, the above conclusions are not prediction but simply an analysis and logical reasoning based on a series of assumptions. In particular, the calculations of growth rates of GDP, fixed asset investment (capital formation) and infrastructure investment are meant only to provide reference and should not be taken as forecasts.

III. Employment target, job creation and economic growth

Job creation is a top priority among Chinese government's growth targets for 2020. Is the employment target achievable? What is the relationship between securing employment and ensuring economic growth?

First, we can take a look at some of the employment figures. In 2019, China's national employment was 770 million, among which 440 million were urban employment (including migrant workers). In terms of employment distribution, the primary sector accounted for 25.1%, or 190 million of total employment; the secondary sector, 27.5%, or 210 million; the tertiary sector, 47.4%, or 360 million; the total employment stood at 776 million.

As for migrant workers, there are separate statistics. The number of migrant workers (those who meet certain criteria to work in cities) reached 290 million. Among them, 170 million were interprovincial migrant workers and 120 million were local workers.

Regarding the change of employment, from 2015 to 2019, employment hovered around 770 million, among which urban employment remained at over 400 million with little changes. The impact of the novel coronavirus outbreak on China's employment has been severe. Compared with the 440 million urban employment at the end of 2019, that in April 2020 dropped to 423 million. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the surveyed unemployment rate in April was 6 %, or 27 million. What is noteworthy is the increase in hidden unemployment, which refers to people who are employed and thereby not included in official unemployment figures but are not working or fully working. In March 2020, hidden unemployment was 76.11 million, and the number of unemployed plus hidden unemployed was 102.2 million. However, the sharp rise in unemployment and hidden unemployment is the result of the COVID-19 shock, and will soon improve once production resumes. In fact, hidden unemployment fell to 14.8 million in April.

How hard will it be to create 9 million new jobs in 2020? Given employment elasticity, we can easily calculate the economic growth rate needed to create 9 million jobs. Given the 442.47 million employment at the end of 2019, 9 million new jobs would mean a 2% increase. There is divergence in the estimation of employment elasticity among Chinese scholars. For instance, Professor Zheng Bingwen at the World Social Security Center of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences places the elasticity between 0.31 and 0.42, indicating that to achieve a 2% employment growth, a 6% and a 4.8% GDP growth would be needed, correspondingly.

It should be noted that even if 9 million new jobs were created, based on the unemployment rate target set in the Government Work Report, unemployment in China will still stand at 27.57 million, higher than that in previous years.

It is entirely correct to make tackling unemployment an important policy goal, which shows the government's concern for people's livelihood. But the growth target and employment target do not conflict with each other, and the view that the growth target should not be emphasized over the employment target is questionable.

As the Chinese saying goes, once the key link is grasped, everything else falls into place. In macroeconomic management, growth rather than employment is the key link. With the growth target set, other social and economic targets can also be determined. But setting other goals based on the unemployment target would be quite difficult. Frankly, employment data is the least reliable among all economic data in China. For instance, the registered unemployment rate in the first quarter of 2020 was even lower than that in the same period of 2019, which was hard to believe. This does not mean that China’s statistical authority is irresponsible. The fact is that there are just too many difficulties. There are so many migrant workers in China, the number of which is hard to calculate. Just because of the different statistical methods used, a gap of 7.65 million exits between urban unemployment and surveyed unemployment in 2019. With this discrepancy, creating 9 million new jobs may not seem to be a daunting task. The problem is: without a GDP growth target and only relying only on the employment target can easily cause policy implementation to go off the track.

What I want to emphasize is: don't pit employment indicators against economic growth targets. In the past, people held that when local governments are required to set economic growth targets, they normally aimed at growth only and tended to make investment blindly. However, there will be more problems if we only care about employment while neglecting economic growth. Without economic growth, how can we increase employment? Local governments will be more at loss when assigned only employment targets. Should they adjust the statistical methods so as to achieve a goal of 2% employment growth? Employ 102 people to do the work that can be easily done by 100? Make government agencies more redundant? Go back to labor-intensive industries that were prevalent in the early stages of reform and opening-up?

In short, talking about stabilizing employment without maintaining economic growth is to fish in the air. To a large extent, it would turn securing employment into providing unemployment relief and lead to lowered labor efficiency. New jobs created without economic growth can only increase hidden unemployment, at a cost of declined per capita income. Dropping the growth target will not address employment problems but may even breed corruption. Changing the industrial structure, such as boosting tertiary industry and labor-intensive industries, could create some room for more employment, but the effect may not be as good as boosting economic growth. Premier Li Keqiang was right to say that development is the key to solving all problems. We cannot solve any problem, including employment, without development and economic growth.

IV. Providing relief should depend on improving the social security system

Although China's economy has begun to recover, the fallout of the COVID-19 outbreak remains there. In addition to resuming production and creating jobs, there is still a lot of bailing out work to do.

How to bail out? Give people money?

During the virus outbreak, Chinese people have relied on three things to tide over financial difficulties. The first is savings. Many people who lost their jobs amid the outbreak have mainly relied on their savings to make ends meet. The second is the country’s social security system. Unemployment insurance, subsistence allowances, rural subsistence allowances, and targeted poverty alleviation policies have all played an important role. The government has also provided a certain amount of temporary relief funds. Third, the rural region served as a reservoir in absorbing migrant workers who returned to their hometowns during the Spring Festival, which helped alleviate the unemployment problem. At present, a very important issue is how to further improve our social security system, especially the unemployment insurance system, and let it better play its role in helping the unemployed and the hidden unemployed overcome the difficulties.

Zheng Bingwen [see endnote 8], Director of the Social Security Research Center of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences pointed out that there are three major problems in China's unemployment insurance system. The first problem is that the proportion of people receiving unemployment benefits to the number of total unemployed is too low. For example, in 2018, the surveyed unemployment rate in China was 4.9%, and the number of unemployed was 21.3 million, but the number of people receiving unemployment benefits at the end of the year was only 2.23 million, accounting for just over 10% of the unemployed.

The second problem is that the claim rate of insured population is also very low. The proportion of people claiming for unemployment benefits in the number of people purchasing insurances have been declining. In 2004, people who claimed for unemployment benefits accounted for only 4% of the insured population. There were 4.2 million people who received unemployment benefits out of 105 million who participated in the scheme at the end of the year. By 2018, this rate dropped to 1.1%. In that year, 2.23 million people received unemployment benefits and 200 million people purchased insurance. Over a span of 14 years, the number of people purchasing insurance has doubled while the number of people receiving unemployment benefits decreased. In other words, more than a decade ago, 100 million people had insurance, which benefited more than 2 million people; more than a decade later, the insured population expanded to 200 million, but the number of beneficiaries remained the same. It shows that the claim rate has dropped by half. Of course, this phenomenon may partly result from lowered unemployment rate. The third problem is that the cumulative balance of unemployment insurance funds has been increasing. Currently more and more people are buying the insurance, but the number of beneficiaries has not changed much. Therefore, the cumulative balance of unemployment insurance funds has increased year by year. In 2004, the balance was 40 billion yuan, and it rose to 580 billion yuan in 2018, an increase of more than 13 times in 14 years.

In the first quarter of 2020, 26-27 million people living in urban areas lost their jobs. According to the World Social Security Research Center of the Chinese Academy of Social Science [see endnote 9], only 2.37 million people received unemployment benefits and one-off living allowances. These situations are hard to believe. It is absolutely necessary to establish a government special fund to deal with emergencies, especially for low-income groups and small and medium-sized enterprises that have made sacrifices to contain the disease. It must be noted that there is still much room to improve our social security system. Even after we successfully overcome the outbreak, the unemployment problem will continue to exist for a long time. We must let the existing social security system better play its role so as to make the whole society enjoy the benefits of economic development and ensure long-term stability of the country.

In short, it is necessary to provide relief funds, especially for enterprises of the service sector that have encountered special difficulties. However, we should also take into full consideration the problems such as operational difficulties and moral hazards. From a long-term perspective, fundamentally speaking, only through two channels can the unemployment problem be resolved, namely economic growth and improved unemployment insurance system. Improving the social security system, including the unemployment insurance system, means that China must reform the current taxation system and enable the whole society to share the benefits of economic growth through income redistribution, so that the unemployed can get basic living security.

The second problem is that the claim rate of insured population is also very low. The proportion of people claiming for unemployment benefits in the number of people purchasing insurances have been declining. In 2004, people who claimed for unemployment benefits accounted for only 4% of the insured population. There were 4.2 million people who received unemployment benefits out of 105 million who participated in the scheme at the end of the year. By 2018, this rate dropped to 1.1%. In that year, 2.23 million people received unemployment benefits and 200 million people purchased insurance. Over a span of 14 years, the number of people purchasing insurance has doubled while the number of people receiving unemployment benefits decreased. In other words, more than a decade ago, 100 million people had insurance, which benefited more than 2 million people; more than a decade later, the insured population expanded to 200 million, but the number of beneficiaries remained the same. It shows that the claim rate has dropped by half. Of course, this phenomenon may partly result from lowered unemployment rate. The third problem is that the cumulative balance of unemployment insurance funds has been increasing. Currently more and more people are buying the insurance, but the number of beneficiaries has not changed much. Therefore, the cumulative balance of unemployment insurance funds has increased year by year. In 2004, the balance was 40 billion yuan, and it rose to 580 billion yuan in 2018, an increase of more than 13 times in 14 years.

In the first quarter of 2020, 26-27 million people living in urban areas lost their jobs. According to the World Social Security Research Center of the Chinese Academy of Social Science, only 2.37 million people received unemployment benefits and one-off living allowances. These situations are hard to believe. It is absolutely necessary to establish a government special fund to deal with emergencies, especially for low-income groups and small and medium-sized enterprises that have made sacrifices to contain the disease. It must be noted that there is still much room to improve our social security system. Even after we successfully overcome the outbreak, the unemployment problem will continue to exist for a long time. We must let the existing social security system better play its role so as to make the whole society enjoy the benefits of economic development and ensure long-term stability of the country.

In short, it is necessary to provide relief funds, especially for enterprises of the service sector that have encountered special difficulties. However, we should also take into full consideration the problems such as operational difficulties and moral hazards. From a long-term perspective, fundamentally speaking, only through two channels can the unemployment problem be resolved, namely economic growth and improved unemployment insurance system. Improving the social security system, including the unemployment insurance system, means that China must reform the current taxation system and enable the whole society to share the benefits of economic growth through income redistribution, so that the unemployed can get basic living security.

V. Outlook for fiscal policy and fiscal situation in the second half of the year

Chinese government rolled out the following fiscal measures to provide relief to people and firms hit by COVID-19: tax cuts and fee reductions, social security exemptions, interest rate discounts, guaranteed government procurement, as well as policies encouraging the production of key medical supplies, and arranging epidemic control and relief funds, etc.

At the current stage, in addition to sustaining fiscal bail-outs, the focus should shift to stimulating the economy for higher-speed growth. How? The answer is to increase fiscal expenditure and provide sufficient funds for infrastructure investment.

China’s fiscal budget is structured differently from that of other countries and has four major items: general public budget, government-managed funds, social security funds, and state capital operations. The first two items are the most important. When we talk about fiscal deficits, we normally refer to the exceeding of expenditure over income in the general public budget. The gap between income and expenditure in government-managed fund is not included in the fiscal deficit. When we say that the fiscal deficit is 3.6%, we refer to the gap between income and expenditure in the general public budget.

According to government data, the estimated national general public budget revenue for 2020 is 21.03 trillion yuan, which includes three parts: revenue in the central general public budget, revenue in the local general public budget, and the carry-over funds. It should be noted that on the surface, the general public budget deficit is 3.76 trillion yuan. But in fact, the general public budget revenue also includes the carryover funds, the unspent balance of previous years being transferred to this year. By definition, fiscal deficit = national general public budget expenditure - national general public budget revenue, which is 3.76 trillion yuan. However, if the carry-over funds of 3 trillion yuan are considered, the national general public budget revenue will be reduced to 18.03 trillion yuan. Then if we subtract that year's actual national fiscal revenue from the budget expenditure, we will get a fiscal decifit of 6.76 trillion yuan. Mr. Liu Kun, Minister of Finance, particularly emphasized this point. Fiscal revenue draws purchasing power from the society through taxes and fees, which restrains the economy. Conversely, fiscal expenditure spends money to stimulate the economy. In this sense, deficit represents a net stimulus. Since the 3 trillion yuan of the national general public budget revenue is not drawn from this year's purchasing power, the stimulus effect of fiscal budget on economic growth should be 6.7 trillion yuan, not 3.76 trillion yuan. Some of the shortfalls in government-managed funds are actually also fiscal deficits. If all things are taken into consideration, we can see that China's fiscal stimulus in 2020 is quite sizable.

According to Chinese standards, China's fiscal deficit has risen from 2.8% in 2019 to 3.6% in 2020; according to the World Bank's broad definition of fiscal deficit, China's fiscal deficit has risen from 7.3% in 2019 to 11% in 2020. Compared with the fiscal deficit rate of 2.7% when the four trillion stimulus package was implemented in 2009, we must say that China’s fiscal stimulus in 2020 is really strong.

Taking into account the size of the Chinese economy, the scale of the current stimulus plan should be much larger than the previous 4 trillion yuan stimulus package. Of course, China should draw lessons from the 4 trillion package. In addition to the waste caused by the haste in implementing projects, the utilization of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) is the key part we should draw lessons from. When the four trillion yuan stimulus package was launched, the central government provided only 1.18 trillion yuan, and the rest was raised by local governments through LGFVs, mainly bank loans. Under this circumstance, the investment plan of the local governments in 2009 exceeded 18 trillion yuan, which greatly exceeded the amount of 487.5 billion yuan required by the central government. At the same time, commercial banks actively lent money in order to meet their business goals (at that time, many responsible companies were unwilling to borrow because of the lack of quality projects while other companies used loans for real estate investment). New loans swelled to 9.6 trillion in 2009. While the economy rebounded, inflation and capital bubbles also deteriorated. Fearing that the economy was overheating, the government began to withdraw from the 4 trillion yuan stimulus plan in 2010. As credit began to tighten, some projects encountered funding difficulties, so shadow banking emerged, and financial chaos broke out. In 2012, we heard a lot about hard landing of China's economy.

From a financial perspective, there are two major problems with the "four trillion stimulus": First, the central government should not let local governments borrow money from banks. The stimulus funds should be provided by the central government, and the deficit should be made up through the issuance of government bonds. Second, China should not quit the stimulus plan in a hurry. China withdrew its stimulus plan in just two years. In comparison, the United States has implemented its stimulus measures until today for more than ten years, though several attempts have been made to withdraw from them. Once the money is lent out and projects are put under way, cutting off the funding suddenly would naturally send the firms to borrow elsewhere. As a consequence, interest rates would skyrocket, and various shadow banks would spring up.

The deficit ratio e is the most important measure of fiscal expansion, but the same ratio may have different stimulus effects on economic growth due to varied budget structures. For the same deficit, the effect of increasing expenditure is different from decreasing revenue (tax). With the same amount of expenditure and income, especially expenditure, different budget structures will result in different stimulating effects.

Should expansionary fiscal policy aim at stimulating consumption or investment? The answer should be "both". But the focus should be on stimulating investment. Consumer demand depends on three factors: income, income expectation and wealth. Due to the large consumption of savings in the early period of the virus outbreak, residents tend to save up their temporary, one-time additional income, and the multiplier effect of fiscal expenditure used to stimulate consumption should be between 0 and 1. In contrast, the multiplier effect of fiscal expenditure used to support infrastructure investment should be significantly greater than 1. Therefore, the main purpose of an expansionary fiscal policy should be to support infrastructure investment, create a "crowding-in" effect, and bring in corporate investment, especially private sector investment.

In order to achieve the goal of a 2.4% real GDP growth or a 3.4%nominal GDP growth, the growth rate of fixed asset investment in the second half of 2020 should exceed double digits, and the growth of infrastructure investment should significantly exceed the growth of fixed asset investment.

How much infrastructure investment can public expenditure support in 2020? Possible sources of funding for infrastructure investment include: central and local government fiscal budgets, central and local government-managed funds, bank loans, local government investment bonds, and others (PPP, etc.). According to the 2020 government budget report, the government can arrange the following funds for infrastructure investment: 600 billion yuan from the central budget, 50 billion yuan of investment into China National Railway Group from the central government, and a large part of the 12.3 trillion yuan of local government funds (about 800 billion yuan comes from the 1 trillion special government bonds issued by the central government, the rest comes from a small part of central government's transfer payments to local governments, special bonds issued by local governments and funds raised from land sale [see endnote 10]). Taken together, the government's financing for infrastructure investment in 2020 is about 13 trillion yuan. Judging from experiences of previous years, government funding for infrastructure investment in 2020 should be around 7 trillion yuan. When the four trillion yuan stimulus plan was implemented during 2009-2010, the central government provided only about 1.18 trillion yuan, and the rest was raised through LGFVs. Comparatively speaking, the government's fiscal support for infrastructure investment in 2020 is very large.

According to Wind statistics, total infrastructure investment in 2019 is 18 trillion yuan. However, after aggressively trimming down the number to reflect the reality, total infrastructure investment in 2019 may be between 11 trillion yuan and 14 trillion yuan. Obviously, the government's fiscal funds are not enough to meet the amount of funds needed to push the growth of infrastructure investment beyond 30% so that the annual growth of fixed asset investment reaches 3.56% [see endnote 11] and the nominal GDP growth reaches 3.4%. Therefore, the government may need to further increase the issuance of Treasuries.

The remaining funding gap can be resolved through bank loans, the issuance of local government investment bonds and other methods (such as PPP, etc.). The fact that China still maintains a trade surplus and current account surplus so far and the obvious signs of contraction in inflation suggest that China's total savings are greater than total investment. Therefore, in theory, it should be possible to use non-governmental funds to make up for the lack of government funds. In other words, the funding issue should not be the bottleneck that restricts the increase in infrastructure investment.

Judging from the current situation, nominal GDP growth in 2020 is likely to be lower than the implied target of 5.4%. As the fiscal budget for 2020 is based on a nominal growth rate of 5.4%, we may fall into the following dilemma in the future:

On the one hand, in order to prevent GDP growth from falling below a certain level, it is necessary to adopt more aggressive expansionary fiscal policy. However, because the nominal GDP growth and fiscal revenue are less than expected, the fiscal situation will deteriorate significantly with further increase in fiscal deficit. On the other hand, if the government reduces fiscal expenditures to prevent the deterioration of the fiscal situation, the economic growth that is already below the potential rate will further decline. What's worse, a further slowdown in China's economic growth will inevitably lead to the worsening of unemployment, an increase in leverage ratio (due to a decline in the GDP growth rate), and a rise in non-performing debts. Consequently, the economy may even eventually fall into a debt-deflation cycle.

In the face of such a dilemma, I think we should choose the first route, which is the "lesser of the two evils", and strive to achieve the highest possible economic growth rate. This approach will definitely produce many fallouts. But growth is the top priority. We should maintain growth first, and solve the resulting problems later.

If China's fiscal situation deteriorates due to lower-than-expected nominal GDP growth, it might make government bonds difficult to sell. In order to enable the smooth sale of government bonds, the central bank may have to implement a Chinese-style QE to offset the crowding-out effect caused by the massive issuance of government bonds.

IV. Monetary policy in the second half of the year and possibility of implementing a Chinese-style QE

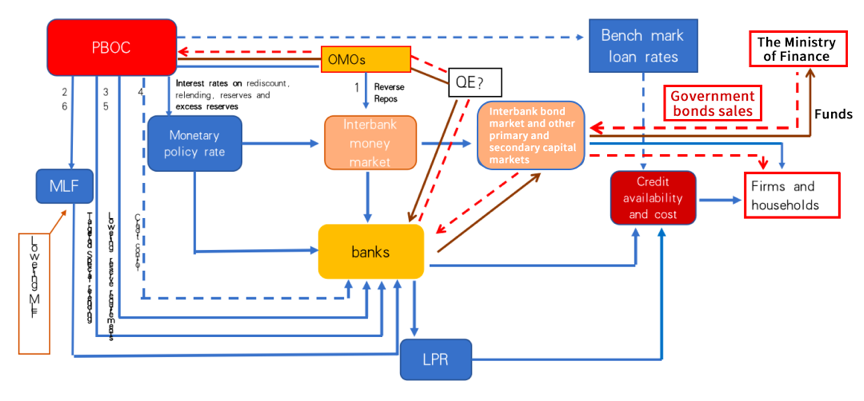

To cope with COVID-19, the central bank has adopted a series of traditional monetary policies and provided relief, especially to help small and medium-sized enterprises tide over the difficulties. Major monetary policy measures include: carrying out reverse repo in the open market; lowering MLF interest rates and guiding LPR quotations downward; issuing low-cost special refinancing; implementing targeted RRR cuts and reduction of excess reserves ratio, etc.

Open market reverse repos can lower the interest rate of the interbank money market, which in turn affects the bank loan market, bond market, and stock market. MLF is used to provides commercial banks with mid-term refinancing and affects the commercial banks' LPR. The central bank also has other policy tools, such as benchmark interest rates, special refinancing, reserve ratio and so on. During the outbreak, the central bank implemented a loose monetary policy and made important contributions to providing epidemic relief (Figure 2).

Monetary policy in 2020 has been relatively loose. However, during an economic contraction, the stimulus effect of monetary policy on boosting growth is limited. Fiscal policy should play the major role, and monetary policy can only serve as the second violinist.

Under normal circumstances, it is not necessary to think too much about fiscal issues when discussing monetary policy. The purpose of implementing loose monetary policy is to enable banks to provide residents and enterprises with low-cost and sufficient credit. However, an important challenge facing the central bank in the second half of 2020 is how to cooperate with the Ministry of Finance to successfully issue government bonds. In 2020, the government plans to issue a total of 8.51 trillion yuan of government bonds. If we also consider the issuance of replacement bonds and refinancing bonds, and the fact that the central government may need to help local governments convert LGFV debts into standardized government bonds and local government special bonds, the issuance of government bonds in 2020 will be significantly higher than that in previous years. In addition, as mentioned earlier, we should also bear in mind that if the nominal GDP cannot achieve a 5.4% growth, the fiscal situation will deteriorate sharply due to the decrease in fiscal revenue.

The large-scale issuance of government bonds in 2020 may lead to an increase in the yield of government bonds, which will have a "crowding-out effect" on private investment and make it difficult to sustain the issuance of government bonds in the future. Therefore, the central bank should not only try traditional monetary policy tools (including lowering the reserve ratio) to release liquidity and restrain the crowding-out effect, but should also consider adopting some unconventional measures.

Due to legal restrictions, China's central bank cannot directly purchase government bonds from the primary market. If, despite the traditional loose monetary policy, financing through government bond issuance still leads to an upward shift in the yield curve, the central bank can consider expanding the scale of open market operations to buy, from the secondary market, the government bonds purchased by commercial banks from the primary market. This is the so-called Chinese-style QE: while the Ministry of Finance sells government bonds to the public on the primary market, the central bank purchases the same amount of government bonds from commercial banks through open market operations (Figure 2).

V. Summary: Growth is Top Priority

There are clear signs of a rebound in the Chinese economy. However, in the second half of 2020, the challenge facing China may be: if we adopt a more aggressive expansionary fiscal policy in order to achieve higher economic growth, the fiscal situation may deteriorate further. If we reduce fiscal expenditure and withdraw fiscal support for infrastructure investment in order to avoid deterioration of the fiscal situation, we will have to accept a lower GDP growth rate. However, if China's economy cannot achieve rapid growth, unemployment and other livelihood issues will worsen, various economic indicators such as corporate leverage ratio and bank non-performing loans will continue to deteriorate, and the economy will eventually fall into a debt-deflation cycle. There is no solution to both issues. The experience of the past 40 years tells us that it is growth that really matters.

Macroeconomic policies discussed in this paper are short-term in nature, which must be discussed under a given institutional setting and structure. However, proper macroeconomic policy is only one of the necessary conditions to ensure sustainable economic growth. The ultimate solution to any major economic problem cannot be separated from the institutional and structural reform and adjustments. For example, the incentive mechanism for local government officials is an urgent problem to be solved. If local officials are indolent and irresponsible, there is no way to maintain sustainable growth even with the most appropriate economic policies.

In fact, the real challenges facing China have long gone beyond the scope of economy. But in any case, if we fully implement the comprehensive reform plan proposed by the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee while adopting a strong expansionary fiscal policy, supplemented by a loose monetary policy, China will not only be able to overcome the impact of COVID-19 epidemic, achieve good economic performance in the second half of 2020, but can also continue to make big strides along the path of sustainable growth. If Chinese economy can stay robust, it will give both Chinese and foreign companies confidence to stay in China.

Endnotes:

1. This article was published in Chinese on July 12, 2020.

2. Investment in fixed assets (excluding rural households): refers to the total workload on construction and purchase for fixed assets during a certain period in the form of currency, as well as the concerning expenses.

3. The total amount of investment in fixed assets was obviously higher than that of capital formation.

4. According to investment data for Jan.-May, 2020 released by National Bureau of Statistics of China.

5. According to investment data for Jan.-May, 2020 released by National Bureau of Statistics of China.

6. Data provided by staff at China Real Estate Association

7. Based on old and new calibers, the figure is 8.3% and 10.9%, respectively. No official data is available.

8. CASS Social Security Lab: Express, June 9, 2020 (vol. 396).

9. CASS Social Security Lab: Express, June 11, 2020 (vol. 397).

10. We assume that the majority of the funds is used for infrastructure investment though the actual situation might not be so.

11. It refers to the growth rate of capital formation.

Download the PDF of the article at: