Abstract: In this paper, the authors first analyzed the impacts of two approaches to fiscal deficit financing (issuing government bonds [Endnote 1] and monetary financing). Based on this analysis and by referring to the US experience of implementing the quantitative easing (QE) policy (a combination of government bond issuance and open market operations), the authors further evaluated the possibility of adopting these approaches in China and their pros and cons. They suggest China can take the following order when choosing financing approaches: first, issue government bonds to non-banking financial institutions (general public); second, issue government bonds to commercial banks; third, launch the Chinese version of QE; fourth, monetary financing. Because of the unique characteristics of the Chinese economy such as high savings ratios in the household sector and high growth rates, China may still be far from having to monetize its deficit. However, this approach should not be ruled out as an option. The current priority is to "stabilize the economic fundamentals". If China sticks to the core target of maintaining economic growth and take pragmatic measures, it should be able to sustain economic growth and solve the various challenges it faces.

Keywords: quantitative easing (QE), monetary financing

In response to the novel coronavirus, China has adopted a more proactive fiscal policy. In the 2020 Government Work Report, China allowed the deficit-to-GDP ratio to exceed 3% for the first time in years. A thorough study of the Report and other official data show that the implied fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratio would far exceed 3%. Against this backdrop, how to finance the deficit has become an important issue in 2020 and years to come.

In fact, prior to the "Two Sessions", the academic community and government research departments had already started a heated debate over how to finance fiscal deficit. We believe such discussions are necessary. As long as both sides could avoid bookishness and dogmatism, and listen to opinions from all angels, they could reach consensus on the basis of logic and facts.

There are four major arguments against monetary financing (monetization of fiscal deficit). First, under China's legal system, the central bank is not allowed to finance fiscal deficit by purchasing government bonds in the primary market. Second, once monetary financing is activated, it might be used repeatedly, which will not only increase the level of the leverage ratio, resulting in bigger debt risk, but also compromise the government's credibility and increase inflation. The third and the most important reason is that the Chinese economy has not yet reached a point where monetary financing must be implemented, and China's high level of savings can be used to purchase government bonds to finance fiscal deficit without causing the crowding-out effect. Fourth, because the biggest problem now is lack of smooth policy transmission mechanisms, as long as conventional monetary and fiscal policies can be implemented effectively accompanied by relevant reforms, and the efficiency of capital utilization can be improved, the objectives of countercyclical adjustment could be fully fulfilled.

On the other hand, support for monetary financing is mainly based on three aspects. First, due to the unprecedented pressure of economic slowdown, the conventional government debt issuance will very likely have crowding-out effect. Second, by turning the formerly implicit quasi-monetary financing process into an explicit one, monetization of fiscal deficit can help strengthen fiscal discipline at all levels. Third, with reduced demand, monetizing fiscal deficit will not cause inflation to get out-of-control.

More experts take a neutral stance toward monetary financing. While they don't think it necessary to take extreme policies like monetary financing yet, they don't reject this proposal totally either, believing that if the economy continues to worsen, monetizing fiscal deficit can be a policy option. This essay is not aimed at reviewing these discussions because some have gone beyond the scope of economics while some others are based on assumptions which can only be tested with more practical experiences. Instead, this essay simply focuses on the impact of different financing methods on the balance sheets [Endnote 2] of the central bank, financial institutions and the government. Based on this and by referring to the QE policy of the US during the global financial crisis, this essay analyzes the feasibility, as well as the pros and cons of China adopting different financing approaches.

I. The difference between bond financing and monetary financing from a balance-sheet perspective

Theoretically, there are three ways for the fiscal authority to finance fiscal deficit, namely, 1) borrowing money from nonbank financial institutions, 2) borrowing money from banks, and 3) borrowing from the central bank. Nonbank financial institutions include pension funds, mutual funds and individuals (the "general public"); for the US, they also include foreign investors such as those from China. Borrowing from nonbank financial institutions is different from borrowing from banks: if fiscal deficit is totally financed by nonbank financial institutions (the general public), money supply will not change; and if it is financed by borrowing from banks, money supply will not change either as long as only the asset structure of banks changes. As both take the form of debt issuance, we divide fiscal financing approaches into two categories: first, issuing government bonds, that is, the fiscal authority issues government bonds to the general public through primary dealers; second, now heatedly discussed, monetary financing, in which the central bank creates money to buy government bonds directly. To simplify analysis, we treat banks as the general public as well. In our analysis, we assume the government issues 100 units of bonds to analyze the different effects of the two approaches.

Scenario 1: bond financing

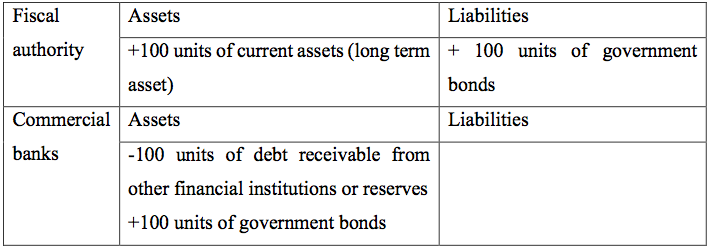

Under this model, the government's balance sheet will see increase of both assets (if in the form of cash, current asset increases; if in the form of investment, long term asset increases) and liabilities (government bonds) by 100 units. Assuming that all government bonds are purchased by commercial banks whose total assets remain the same (only the asset structure would change), the banks' assets will increase by 100 units in the form of government bonds, while either reserves will reduce by 100 units if the bonds are purchased with excess reserves, or debt receivables from other financial institutions will reduce if the bonds are purchased with cash. During this process, no change will occur in the value of assets or liabilities on the central bank's balance sheet (though the structure of liabilities might change).

Table 1: Changes in the balance sheets of the fiscal authority and commercial banks when fiscal deficit is financed by government bond issuance

Bond financing will not lead to increase of money supply, hence will not create inflation. However, issuing new bonds to the general public may cause interest rates to rise which can have crowding-out effects on private investments.

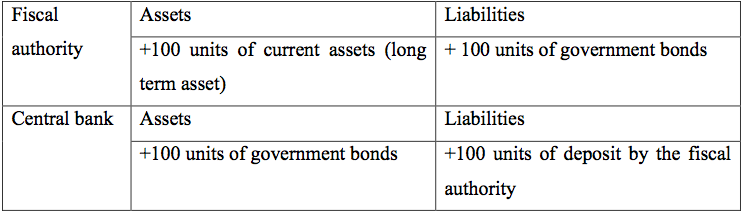

Scenario 2: Monetary financing

Under this scenario, the balance sheet of the fiscal authority remains the same as that under scenario 1; but the assets and liabilities of the central bank will each increase 100 units, with the assets increasing by 100 units of government bonds. As the bonds are purchased from the fiscal authority directly through the creation of new money, the increase of liabilities is reported as an increase of the fiscal authority's deposit at the central bank. While the central bank's assets increase by 100 units of government bonds under both methods, the liabilities increase by 100 units of M0 or M1 under monetary financing [Endnote 3] In other words, monetary financing increases money supply.

Table 2: Changes in the balance sheets of the fiscal authority and the central bank under the monetary financing model

Because monetization of fiscal deficit requires the central bank to create additional money, it will not have crowding-out effect on private investments. However, it will increase monetary supply by an amount equal to the fiscal deficit, hence the risk of inflation will rise, which is why many economists in China argue against this approach.

II. Quantitative easing policy of the US, a practice of indirect monetary financing

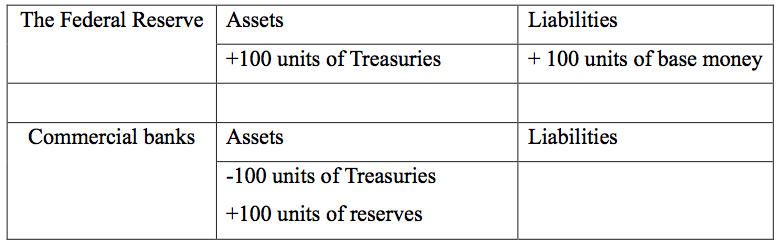

In the third quarter of 2008, the subprime mortgage crisis deteriorated rapidly in the US. To stabilize the financial system and stimulate economic growth, the Federal Reserve launched the quantitative easing policy (QE) drawing on Japan's experience. At first, the Fed and many US economists emphasized that QE was simply an expansion of the open market operations (OMO). OMO is the major monetary policy instrument of the Federal Reserve by which the Fed sells and purchases short-term Treasury bills to adjusts the Federal funds rate. OMO works directly on the balance sheets of commercial banks and the central bank, but has no direct impact on the balance sheet of the Treasury.

Table 3: Impact of OMO on the balance sheets of the Fed and commercial banks

It can be easily seen that if the central bank purchases 100 units of Treasuries from commercial banks [Endnote 4] through OMO, reserves of commercial banks at the central bank will increase by 100 units. The change of commercial banks' balance sheet is as follows: on the assets side, while government bills are reduced by 100 units, reserves are increased by 100 units; on the liabilities side, nothing is changed. For the central bank, while assets are increased by 100 units of Treasuries, liabilities are increased by 100 units of commercial banks' reserves. It should be noted that the Fed's OMOs is not directly related to the Treasury's management of Treasuries (the issuance of Treasuries to finance fiscal deficit).

The Fed can purchase a large amount of Treasuries, corporate bonds and asset-backed securities on the market. In appearance QE and OMO are very similar. There are 24 primary dealers in the US who could deal directly with the Fed including qualified banks and securities firms such as Morgan Stanley, Barclays, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and so on. These primary dealers participate in the auctions of newly issued government bonds (Dutch Auction) organized by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on behalf of the Department of the Treasury. The Fed can only purchase the Treasuries from these primary dealers on the secondary market, rather than directly from the Treasury. [Endnote 5]

During the fifty years from the 1950s to the 1990s, as part of the conventional monetary policy, OMO is mainly used by the Fed to adjust the federal funds rate and the growth of broad money supply by changing the amount of liquidity in the market. As the correlation between money supply growth and the actual performance of the economy became increasingly uncorrelated, the Fed no longer treated the growth of money supply as a policy target after July 2000. In 2006, the Fed stopped releasing data of M3, a measure of broad money supply. [Endnote 6] Until the eve of the 2008 global financial crisis, the purpose of OMO had been maintaining the federal funds rate at the target level by adjusting the supply of reserve funds in the interbank money market through the purchase and selling of Treasuries. The OMO has nothing to do with the management of Treasuries. For instance, even when there is a surplus in fiscal revenue and the Treasury didn't issue new bonds, in order to cut the federal funds rate, the Fed will still purchase Treasuries in the secondary market to inject liquidity into the interbank market.

After the outbreak of the subprime crisis in 2008, the Fed first cut the federal fund rate to almost zero. From the end of 2008 to 2014, the Fed purchased a large amount of Treasuries with various maturities through OMO, in particular long-term Treasury bonds. This was known as the quantitative easing (QE) policy.

With the QE policy, the Fed purchases US Treasury bills at a much larger scale than it would normally do under OMO, and most of the Treasuries purchased are long-term. In addition, the Fed also bought a lot of junk bonds. In the early days of implementing QE, the Fed and many US economists emphasized that it had nothing to do with monetary financing or monetization of fiscal deficits. It was merely an enhanced version of OMO.

In addition to the objectives of conventional OMOs, QE also has another four explicit or implicit policy objectives: first, push down long-term interest rates to reduce long-term financing costs; second, curb the decline of prices of toxic assets through purchase of ABSs; third, lower the yield of Treasuries to push up the stock market; fourth, indirectly monetize fiscal deficit. The first three are all market consensus, and we will elaborate on the fourth point below.

Since the subprime crisis, the Fed's OMO has been closely coordinated with the Treasury's fiscal stimulus policy. In 2008, the ratio of the US fiscal deficit to GDP was only about 3%, and in 2009 it jumped to more than 10%. Under such circumstances, if only Treasury bonds were used for financing fiscal deficit, the yield of Treasuries will inevitably rise significantly. The recession that followed the collapse of the subprime bubble, however, required the Fed to maintain a near-zero interest rate. In this case, to serve the dual needs of financing large-scale fiscal deficits and maintaining low interest rates, the Fed and the Treasury worked together to implement an alternative financing approach that is different from monetary financing or bond financing, i.e. bond financing + OMO.

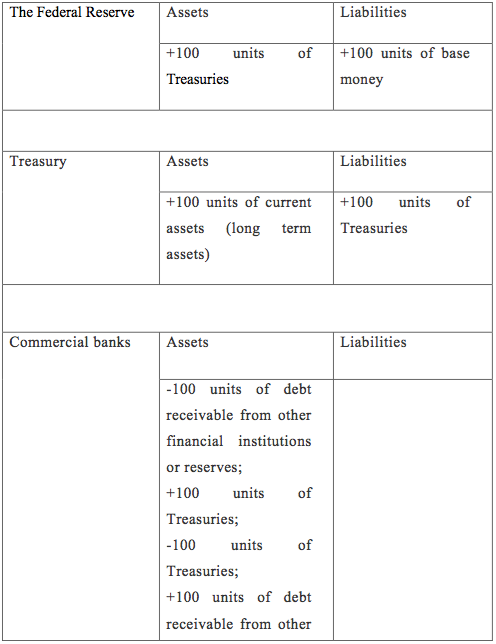

Scenario 3: bond financing + OMOs

First, the Treasury sells bonds to primary dealers to finance the deficit. This would lead to changes in the balance sheets of the Treasury and commercial banks as shown in Table 1. On the balance sheet of the Treasury, assets would increase by 100 units of cash (or deposits), and liabilities would increase by 100 units of Treasury bonds. Commercial banks would have their assets increase by 100 units of Treasury bonds, and decrease by 100 units of other assets (we can assume a reduction of 100 units of excess reserves). This approach is standard bond financing. Most of the bonds sold by the US Treasury have been bought by foreign investors such as pension funds and mutual funds from China and Japan, only a small part is held by US banks.

Secondly, the Fed conducts OMO and buys a considerable amount of Treasury bonds from banks in the secondary market. The impact of this operation on the balance sheets of banks and the Fed is shown in Table 3. The Treasury bonds held by banks decreases by 100 units, but their reserve increases by 100 units. At the same time, the assets on the Fed's balance sheet increase by 100 units of Treasuries, and the liabilities increase by 100 units of the banks' reserve deposit with the Fed. As shown in Table 4, as a result of "bond financing + OMO", changes to the balance sheet of the Treasury are still the same as in the previous two scenarios. For the central bank, the process of conducting OMO is the process of creating or eliminating money. The result of purchasing Treasury bonds from commercial banks is an increase of 100 units of Treasury bonds on the asset side, and an increase of 100 units of reserve deposit on the liability side. For commercial banks, when 100 units of Treasury bonds purchased from the primary market are bought by the central bank through OMOs, asset structure in their balance sheets may change, but the total assets and liabilities will remain the same.

Table 4: Changes in the balance sheets of various parties as a result of government bond financing and OMO

From the Treasury's perspective, no matter which method is used, it always obtains the needed financing, but the impacts of the three approaches on the economy are different. In the first scenario, bond financing will not create additional money. But because commercial banks use their own funds to purchase Treasuries, funds available for private investment will be crowded out, and market interest rates will rise.

Monetary financing in scenario 2 and "bond financing + OMO" in scenario 3 are the same according to Ben Bernanke. In his famous speech on "helicopter money" in 2002, he clearly pointed out: "A tax cut financed by money creation is the equivalent of a bond-financed tax cut plus an open-market operation in bonds by the Fed." [Endnote 7] But the authors believe that there is still a certain difference between the two. The former increases the Treasury's deposits on the central bank's balance sheet, and increased the supply of M0 or M1.

An increase in money supply will increase inflationary pressure. However, as a result of "bond financing + OMOs", the increase in the liability end of the central bank's balance sheet is base money, that is, the reserves deposited by commercial banks in the central bank, and there is uncertainty over whether the increased reserves will increase inflation pressure. Reserves are not money in the general sense, and no one can use reserves to purchase goods and services. The increase in reserves means enhanced capacity of commercial banks to make loans. In the case of insufficient demand or deflation, banks are reluctant to lend, and households and businesses are reluctant to borrow. So an increase in reserves does not necessarily lead to an increase in broad money supply. Commercial banks may deposit their cash obtained from selling Treasury bonds into the central bank in the form of excess reserves. At this time, the newly added base money will not go into circulation, and thus won't increase inflationary pressure.

Therefore, although the "bond financing + OMOs" approach can be regarded as an alternative to monetary financing to a certain extent, it is not entirely "helicopter money" and will not immediately translate into inflationary pressure. In order to distinguish it from "bond financing + OMO", we call the Fed's implicit monetary financing "bond financing + QE".

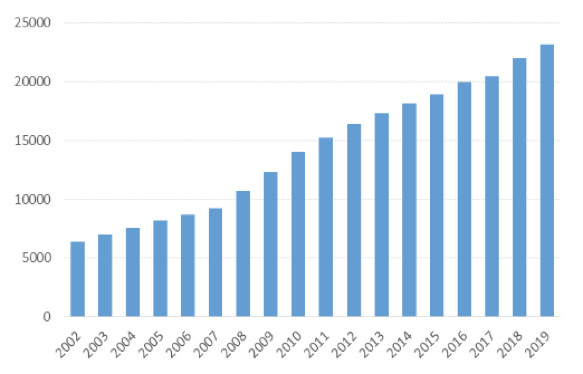

After 2008, the amount of newly issued US Treasury bonds expanded rapidly, from an average of US$ 2-3 trillion per year to US$ 5 trillion annually. The expansion also caused the outstanding balance of Treasuries to rise rapidly, from US$ 10 trillion in 2008 to US$ 23 trillion at the end of 2019.

Two observations can be made from the classification of asset holders and changes of the Fed's balance sheet -

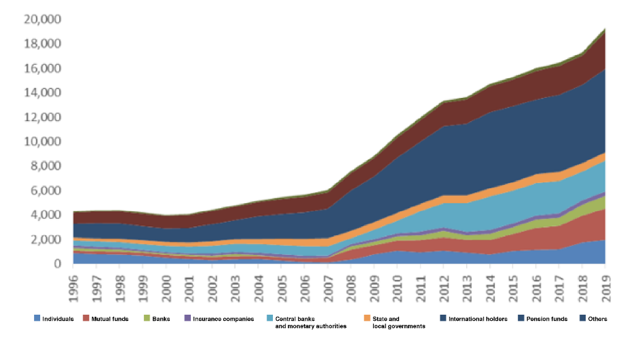

First, foreign investors such as China and Japan, the Federal Reserve, and pension funds are the main buyers of US Treasury bonds, and their holdings of US Treasuries increased by US$ 3.6 trillion, 2.1 trillion, and 1.7 trillion, respectively.

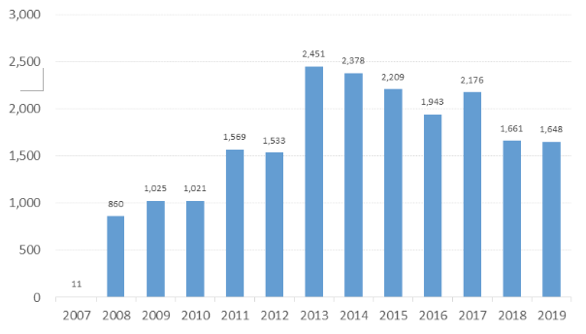

Second, on the liability side of the Fed's balance sheet, reserves of commercial banks (including statutory reserves and excess reserves) grew rapidly, from US$ 11 billion in 2007 to US$ 1.6 trillion in 2019, and in some year it even reached US$ 2.5 trillion. Super-large commercial banks are underwriters of US Treasury bonds, but do not hold large amounts of Treasuries themselves. Normally, after buying Treasuries on the primary market, they will resell them to foreign investors, pension funds, and other financial institutions. The assets they hold are mainly housing mortgage loans and other traditional types of loans.

Traditional OMO would reduce the amount of Treasury bonds on the secondary market, such as those held by commercial banks (the target of OMO). With QE, more Treasury bills are issued, so we don't see an increase of the central bank's holdings of Treasuries accompanied by a simultaneous decrease of holdings by commercial banks and other investors which is common under OMO. The sharp increase of commercial banks' reserves shows that as underwriters have sold huge amounts of US Treasury bills to the Federal Reserve, rather than traditional investors in the secondary market. At this time, the purpose of the Fed's OMO is not only to regulate short-term interest rates, but also provide monetary financing for the fiscal deficit.

In fact, a considerable portion of the newly issued Treasury bonds are sold to the Federal Reserve by commercial banks who act as primary market dealers. The process by which the Fed buys government bonds through OMOs is also the process of money creation. In the implementation of QE, commercial banks acted as an intermediary between the Treasury and the Fed, allowing the Fed to indirectly finance the fiscal deficit.

If Bernanke had much reserve when talking about monetizing fiscal deficit, Richard Fisher, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas is much more forthcoming. He pointed out: “The Federal Reserve will buy $110 billion a month in Treasuries, an amount that, annualized, represents the projected deficit of the federal government for next year. For the next eight months, the nation’s central bank will be monetizing the federal debt.” [Endnote 8] This doesn’t happen only in the United States, but also in other countries. Jean-Claude Trichet, the former European Central Bank President, admitted in an interview with Caixin that major developed countries have practiced de facto deficit monetization since 2008. [Endnote 9]

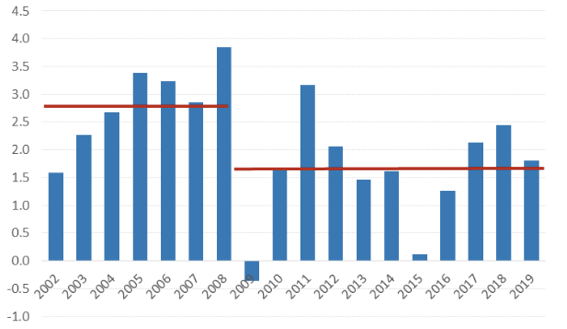

Although the policy combination of "bond financing + QE" has led to a substantial increase of base money, due to insufficient demand, banks are not willing to lend. Although the growth of base money is staggering, the growth of broad money remains stable, while the average annual growth of CPI dropped from 2.8% in 2002-2008 to 1.6% in 2009-2019.

The policies adopted by the United States during the global financial crisis have been proven relatively successful at least in the past 10 years. The US Treasury and the Fed worked with each other and successfully realized large-scale bond financing and monetary financing without causing inflation. The purchase of Treasury bonds by the central bank has directly lowered the yield of Treasury bonds and greatly reduced financing costs. For example, after the global financial crisis, the US Treasury Department issued about US$ 5 trillion debt each year. Financing costs can be reduced by US$ 100 billion assuming there are cost reduction of 200 base points.

The success of the QE policy depends on two conditions: First, at the beginning of the global financial crisis, a series of policy measures by the US government stabilized the market including foreign investors' confidence in the US economy and the US dollar, and the size of US Treasuries held by foreign investors and hedge funds is larger than that of the Fed. Second, the US economy continues to be under deflationary pressure. Because the banking system is reluctant to lend, money supply does not increase with the increase of reserves, and prices have been very stable over the past decade.

Although the United States did not experience uncontrolled inflation that people initially feared, drawbacks of the QE policy are also obvious. For example, it has caused a huge stock market bubble; the massive reserves may be released at any time and increase inflationary pressure. The US Fed alluded in 2013 that it would exit QE for fear that deficit monetization would lead to hyperinflation and the burst of asset bubbles as the economics textbooks said. But compelled by the US economic situations, it continued with QE and at least partial deficit monetization for 14 years, and by now, its balance sheet has swelled to over US$ 7 trillion. Nobody knows when the "house of cards" will collapse.

Figure 1: Value of US Treasuries (in billion US$)

Source: Wind database

Figure 2: Value of US Treasuries by types of holders (in billion US$)

Source: US Fed

Figure 3: Reserve deposit at the Fed (in billion US$)

Source: Wind database

Figure 4: CPI growth of the US (%)

Source: Wind database

III. China's options

1. Theoretically or practically speaking, monetization of fiscal deficit is not necessarily a no-no.

It has been repeatedly stressed hereinbefore that monetary financing or monetization of fiscal deficit is not necessarily a no-no.

In fact, most of the major developed economies are doing that to various extents. No central bank in the world will publicly announce that they are doing it, but we can tell that from their practice, not to mention that many central bankers have already acknowledged it. It would be unwise to stick with traditional theories and place too much trust on what the central banks officially say.

Similarly, it would be unwise for China to blindly follow what the US and other countries do. Whether to adopt fiscal deficit monetization should be solely based on the actual demands and situation of the Chinese economy, rather than what we are told by books or others. As said before, the Chinese government and academia basically have two concerns over monetary financing: first, it could disrupt fiscal discipline, and the government and the central bank could lose their credibility; second, it could add to inflationary pressure and cause the asset price bubble to further swell.

These are reasonable worries. When the economy is running normally, it's important that the government and the central bank follow due fiscal discipline, and maintain their credibility and people’s confidence in the currency. But when the economy contracts, we must roll out extraordinary measures for the extraordinary time, to save the economy from a free fall or even a collapse which could result from insufficient countercyclical measures. Economists usually speak against immediate stopgap measures out of "long-term considerations", but how long is "long term"? Five years? Ten years? The world is too uncertain for us to plan everything ahead. When the fire alarm goes off, the first thing should be to put out the fire, while all possible consequences shall be dealt with afterwards.

When the economy is under deflation pressure, monetary financing will not necessarily cause inflation. China issued 4.1 trillion yuan of government bonds in 2019, and if all had been done through monetary financing, M1 would have increased by the same amount. With M1 standing at 55.1 trillion yuan at the end of 2018, growth of money supply would have registered an extra 7.4%. Since 2018, M1 had been growing at a rate of 3-5%. With monetary financing, the growth in 2019 should have been elevated to around 12% if no other factors are taken into account. That is not much higher than the level before 2017.

Back in 2015 and 2016, as a result of several macroeconomic policies, M1 used to grow at over 25%, the highest speed ever since the global financial crisis. But because of insufficient demand, CPI continued to grow at around 2% or less, while PPI saw negative growth for 54 consecutive months since March 2012. In other words, with insufficient demand, M1 growth propelled by stimulus policy will not necessarily induce inflationary pressure. This has been seen in many countries. As the relationship between money supply and inflation becomes increasingly obscure, most developed countries no longer treat growth of money supply as an intermediate policy target, but have switched to inflation targeting.

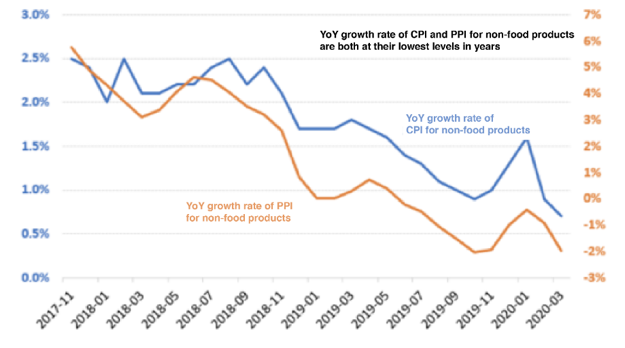

China is still facing deflationary pressure caused by insufficient demand. PPI has been experiencing negative year-on-year growth ever since February at an increasing rate. The year-on-year growth of CPI for non-food products has been lower than 1% for three months in a row, and we are now fully aware that the previous hike in food prices was mainly due to shortage of supply rather than higher demand. Increase in supply would relieve the upward strains on the CPI, and it turned out that the month-over-month growth in food prices actually dropped in March and April.

As for worries about further swell in the asset price bubble - empirical studies have shown that a large amount of liquidity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for creating asset bubbles. Current valuations in the Chinese stock market are reasonable in general, and the economic downturn has suppressed the upward momentum in asset prices. As long as the easing policies are implemented appropriately, a large-scale asset price bubble is not very likely. The key regulatory focus should be on preventing over-concentration of funds in certain industries or companies for speculation purposes.

In conclusion, at this unusual time, if China's supply capability remains intact, and the major problems are insufficient demand, a growth rate that is lower than the potential rate and severe unemployment, policymakers can consider some extraordinary measures for countercyclical adjustment, including monetary financing.

Figure 5: Fluctuations in price indexes for non-food products

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics of China; Wind database; estimates by the authors.

Figure 6: Capital market fluctuation is not strongly correlated with M2 growth rate

Source: Wind database

2. Possibility for implementing the Chinese version of QE in the future

According to the Two Sessions, China's general public budget is seeing a deficit of 3.76 trillion yuan in 2020; meanwhile, the aggregate fiscal revenue is 6.7 trillion yuan short of the budget, and the Chinese government is planning to issue special bonds of 1 trillion yuan, while the planned issuance of local government special bonds stands as high as 3.76 trillion yuan in aggregate. Considering these, the actual fiscal stimulus injected into the economy may be much higher than what the deficit ratio of 3.6% reflects, although still lower than market expectations.

In addition to the drive to raise funds for its 2020 fiscal spending, the Chinese government also needs to issue new bonds to repay old debts, and may have to help local governments to convert their debt on the financing vehicles (LGFVs) to standard government bonds, local government bonds and local special bonds. Latest information suggests that various types of bonds that the Chinese government plans to issue in 2020 will mount to at least 8.5 trillion yuan, and the number may be even bigger if we include implicit government debts which are not officially counted as government bonds. Total financing in the primary bond market was 45 trillion yuan in 2019, and government financing accounted for 20%. The kind of stress that government bond issuance in 2020 will place on the Chinese capital market need to be further studied. Generally speaking, if not supported by interest rate cuts or other proper monetary policies, the issuance of government bonds is very likely to squeeze the liquidity available for financial institutions, push up the yield curve and the financing costs. As a result, the Chinese economy will not be able to reach its full growth potential.

Deficit financing could be arranged in the following order: first, issue government bonds with various terms to non-bank financing institutions (the general public); second, issue government bonds to commercial banks; third, try out the Chinese version of QE; and finally, turn to the last resort of monetizing fiscal deficit. The central bank should also adjust the monetary policy accordingly to facilitate the issuance of government bonds.

When the government issues bonds to the general public and commercial banks, the People's Bank of China (PBOC) should reduce the required reserve ratio based on changes of the bonds' yield curve, release liquidity into the market and curb the crowding-out effect. Based on the experience of special government bond issuance back in 1998, the central bank can reduce the required reserve ratios for some of the commercial banks which can then use the additional money to buy special government bonds, while the interest rates of these bonds could be set at levels similar to that on excess reserves.

The PBOC is prohibited by law from directly purchasing government bonds on the primary market. But if the yield curve of government bonds continues to rise despite the easing of monetary policies such as required reserve ratio cuts, benchmark interest rate cuts, reverse repos, and reductions in medium-term lending facilities, the central bank could consider changing the approach and scale of open market operations (e.g. stopping reverse repos and turning to direct purchase), and roll out the Chinese version of QE. If QE cannot lower the yield of government bonds to acceptable levels either, the country may have to turn to the last resort of monetary financing.

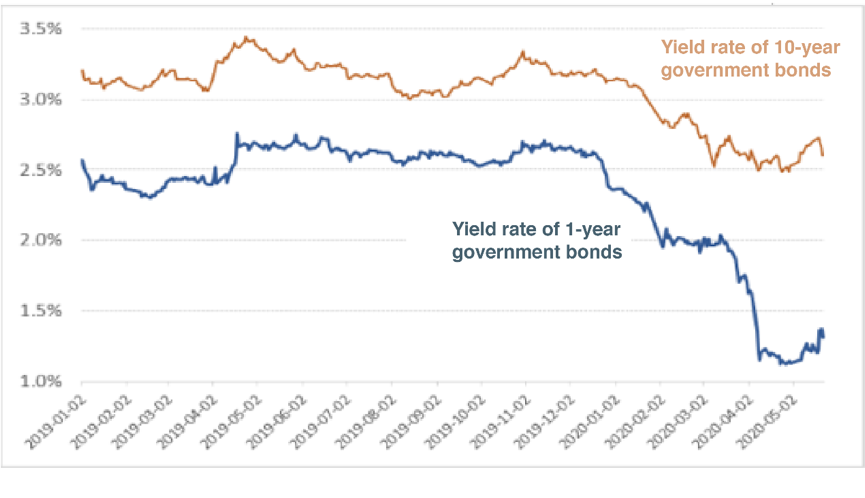

Since March, after multiple required reserve ratio cuts and interest rate adjustments, the interest rates of short-term bonds have dropped significantly, but those of long-term bonds have only seen slight declines. For example, the yield on 1-year government bonds trended down from 2.36% in early January to the current 1.31% by 105 base points; during the same period, the yield of 10-year government bonds only decreased by 55 base points in contrast. However, with the injection of liquidity slowing down, the interest rates of government bonds with various maturities have all bounced back to different extents ever since May. In the meantime, the interest rate spreads of credit bonds remain at around 100 base points, similar to the level back in May, 2019. Out of concerns over inflation and insufficient monetary easing, market participants have expressed doubts about whether the yield rate of 10-year government bonds could drop below 2.6% (see Figure 7). Recent developments have shown that liquidity ease in the short term can hardly slash the long-term yield rates.

But if the central bank rolls out QE and purchases long-term government bonds on the secondary market, it will be able to do that and reduce the financing costs of the real economy.

If QE is implemented and the central bank starts to purchase assets from commercial banks, its balance sheet will see more excess reserves, and the monetary base will be expanded. But just as the experience of the United States shows, under mounting downward pressure, it is difficult to transfer base money to the real economy. That's why we may not need to worry too much about inflation.

Last, we want to emphasize that given the high savings ratio and high growth rate, the Chinese economy may be far from having to monetize its fiscal deficits. However, we should not rule out the possibility of taking extraordinary measures for extraordinary times in the first place.

Figure 7: Fluctuations in the yield rates of government bonds with different maturities

Source: Wind database

IV. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has set off a bigger tumult in the global financial market than the 2008 financial crisis, and the future remains unpredictable until the virus is brought under control. These uncertainties are partly why China did not set an economic growth target this year. But just as reiterated in the Government Work report, the top priority for the country is to stabilize the fundamentals of the economy. As Premiere Li Keqiang said, development remains the key to and the foundation for resolving all the problems in China today. A medium to high growth rate underpins sound growths in fiscal revenues, business profits and household income, and facilitates the adjustments of the growth model and economic structure. China also needs to step up industrial upgrading to boost demand, encourage innovation, and increase the momentum for sustainable economic growth.

Past experiences tell us China needs to stick to the core goal, i.e. economic growth; all policies must be flexible and reality-based, rather than rigidly based on traditional theories. Only in this way can the country sustain its economic growth and successfully address the various problems and challenges it faces.

Endnotes:

i.In most cases, the term ‘government bonds’ in this paper refers to bonds issued by the central government. However, occasionally, it refers to bonds issued by both the central government and local governments.

ii.The fiscal authority is the subject of the implementation. The narrow meaning of government balance sheet does not include state-owned enterprises.

iii.The fiscal authority will not deposit funds at the central bank for a long time, and once the funds are "used", currency in circulation in the society will increase.

iv.Here refers to the "general public" which include commercial banks.

v.Historically, the selling of the US Treasuries had been conducted jointly by the Federal Reserve and the Department of the Treasury until March 1951 when the two signed agreement to separate the management of Treasuries and monetary policy.

vi.https://www.newyorkfed.org/aboutthefed/fedpoint/fed49.html

vii.Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke, Before the National Economists Club, Washington, D.C., November 21, 2002.

viii.Imad Moosa: Quantitative Easing As A Highway to Hyperinflation, p270, World Scientific, Singapore, 2014.

ix.An interview with Jean-Claude Trichet: European approach beyond monetization of fiscal deficits. Posted on Caixin on May 26, 2020.