Abstract: This article makes three observations of China's macroeconomic figures for Q1 2020. First, total economic output and the general price level have experienced highly diverging fluctuations: the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on China's output is two to four times that of the financial tsunami in 2008, while the influence on the price level is only 20% of that twelve years ago, which means policymakers should attach equal importance to both demand and supply. Second, both online and offline spending have plunged, indicating complexity of consumer behaviors under the shocks. Third, some sectors, businesses and population groups have taken significantly larger blows than others, and it is important to support them with transfer payments, which may be less effective in boosting demand than infrastructure investments, but can help preserve capital stock without distorting resource allocation.

I. Economic output and general price level have shown significantly diverging trends

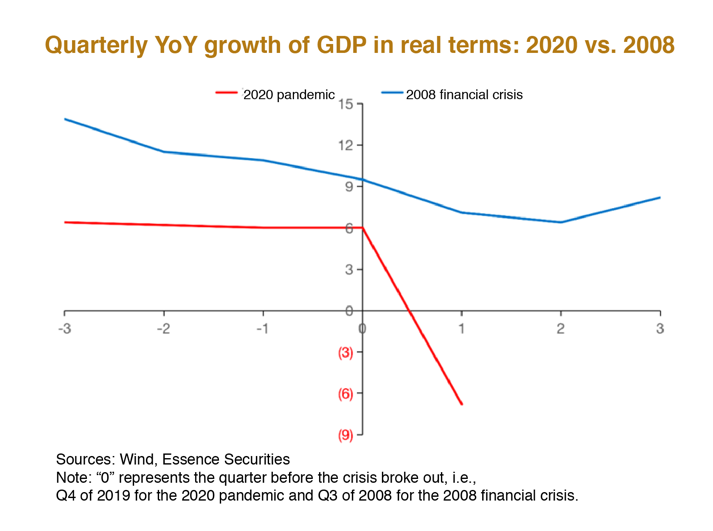

The pandemic has dealt much larger blows to the economic aggregate than the financial turmoil in 2008.

According to the macroeconomic data of the first quarter of 2020, under the COVID-19's impact, the economic growth rate has slumped by four times as much as that 12 years ago.

Figure 1: Impacts of the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic on economic growth

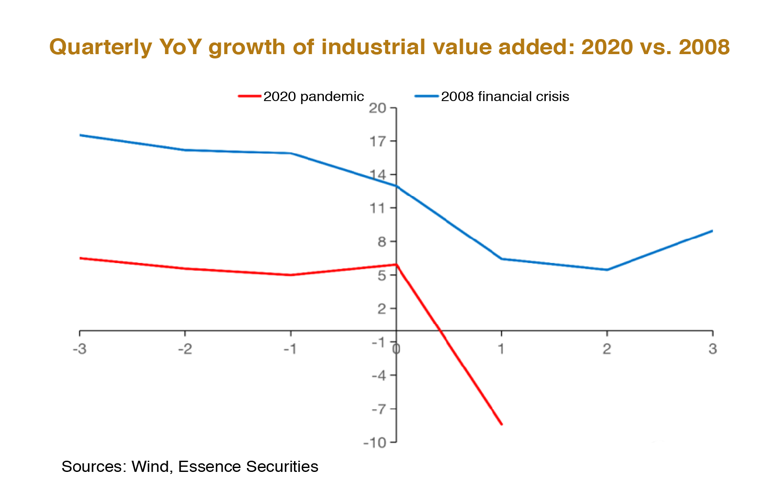

In addition, while both crises have slashed the growth of industrial output, the pandemic has taken a bite twice as big as that by the financial turmoil out of the growth of industrial value added.

Figure 2: Impacts of the financial crisis and the pandemic on industrial value added

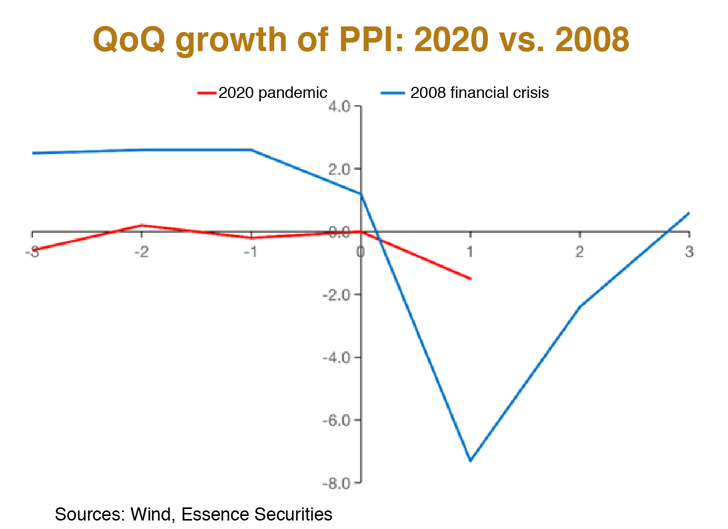

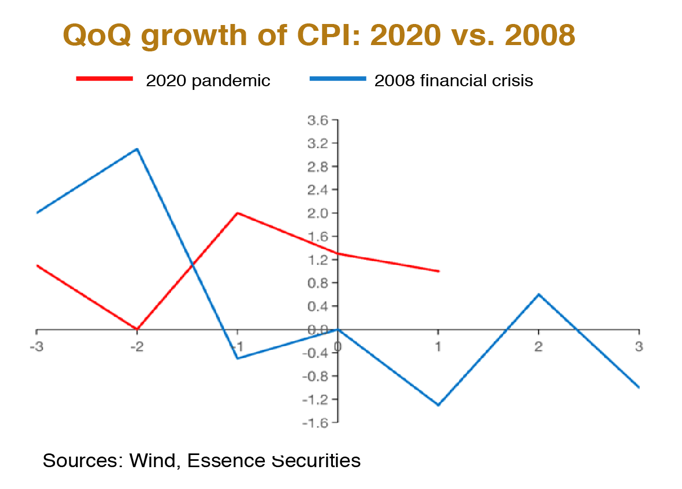

However, the pandemic's blow on the general price level has been much less severe than that of the financial crisis.

If we look at the fluctuations of the producer price index (PPI), it's clear that both crises have significantly disturbed the price of industrial products, but the slump in the price amid the pandemic was only about 20% of that in the financial turmoil.

Figure 3: Impacts of the financial crisis and the pandemic on PPI

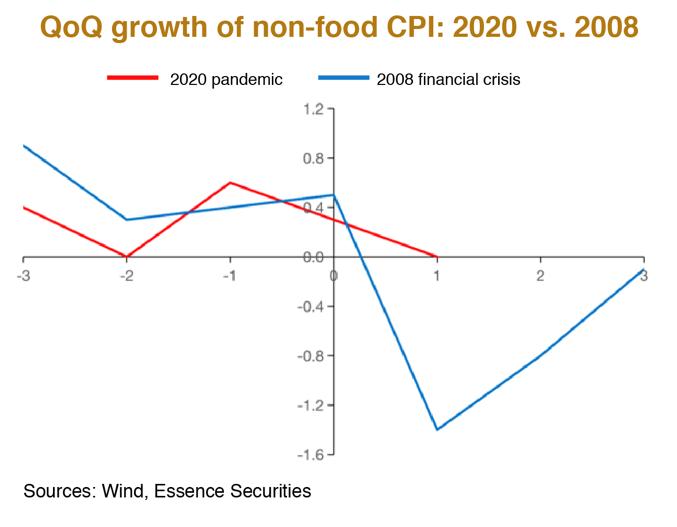

In terms of non-food consumer price index (CPI), even if we assume that the virus is solely to blame for the fall in non-food CPI amid the outbreak, the strain that the financial turmoil placed upon the price was way bigger than the pandemic.

Figure 4: Impacts of the financial crisis and the pandemic on non-food CPI

As for the general CPI, the cut in the price level amid the pandemic was only about 20% of that during the financial crisis, similar to the relative decline in the price of non-food commodities.

Figure 5: Impacts of the financial crisis and the pandemic on CPI

The figures for total economic output and general price level have shown sharp contrast: the impact of the pandemic on the economic aggregate was two to four times as large as that of the financial crisis, while its blow on the general price level was only 20% of that back in 2008. Judging from the pattern of economic fluctuations in the past dozen or so years, the dent the pandemic made in the price level equals the slowing of industrial activities by 0.5% or the slackening of GDP growth by 0.3%. In other words, the pandemic has generated impact on price similar to that of a mild economic slowdown, but in terms of economic outputs, the blow of the virus is unprecedented and several times worse than that of the financial turmoil.

Why is there such a huge contrast?

This is because the COVID-19 outbreak has disturbed both aggregate demand and aggregate supply. On one hand, the pandemic significantly curbed consumer spending and investment activities, causing the aggregate demand to drop dramatically in a short time; on the other hand, production and services were brought to a standstill by lockdown measures imposed across the entire economy, resulting in a plunge in aggregate supply. The simultaneous falls in both aggregate demand and aggregate supply were manifested on the output end as the tumble in production activities, but because the gap between demand and supply was not that large, the price level only descended moderately.

Based on the price elasticity of industrial production and the consumer's price elasticity of economic growth in general, the aggregate demand is likely to drop by around 7% because of the pandemic, and the aggregate supply by a slightly lower 6% plus.

The policy implication of that is, before the restrictions on aggregate supply are lifted, stimulating aggregate demand alone may not be enough to achieve the anticipated results, if not inducing inflation instead; on the contrary, if we gradually resume production activities while keeping the virus under control, the economy will recover as a matter of course. Hence, policymakers should not rely too much on aggregate demand management; instead, fluctuations in both aggregate demand and supply as well as the gap in between and how it changes over time deserve equal considerations.

II. Panic and the decline in online transactions

Consumer behaviors have changed a lot during the pandemic:

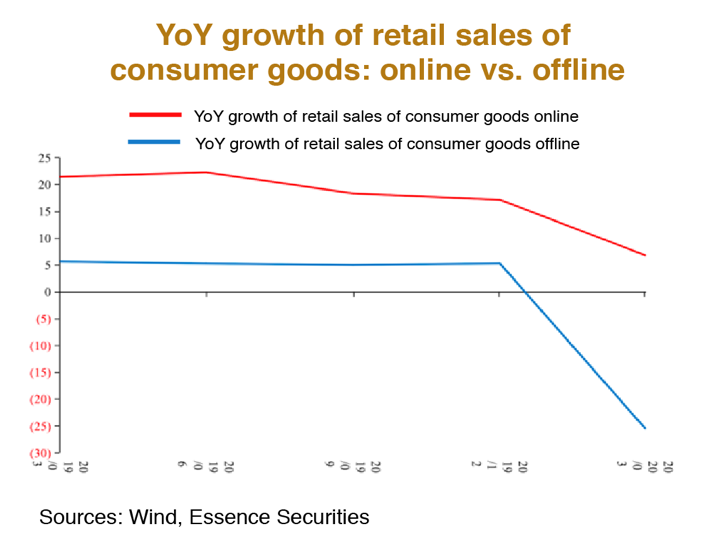

In aggregate, both offline and online spending have seen huge declines.

Figure 6: Impacts of the pandemic on online and offline spending

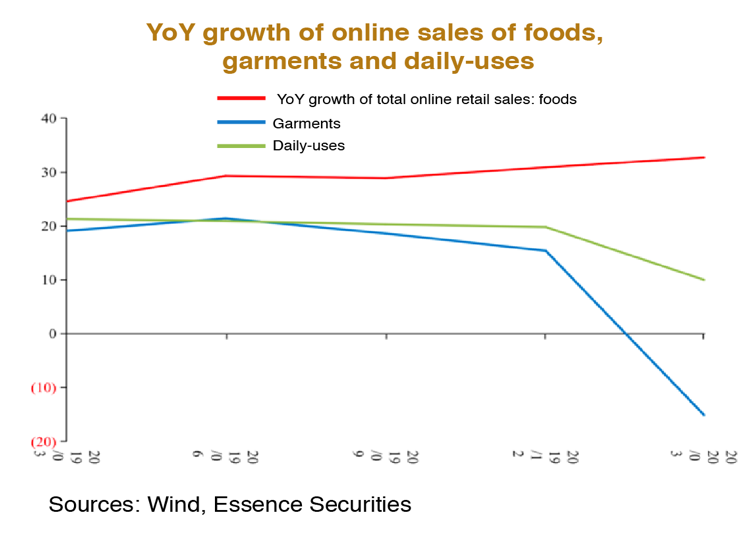

In terms of specific categories of products, online transactions of foods have remained normal, or even got marginally boosted because some of the offline transactions have moved up online. However, online demands for non-necessities such as garments and daily-uses have significantly decreased.

Figure 7: Impact of the pandemic on online sales of foods, daily-uses and garments

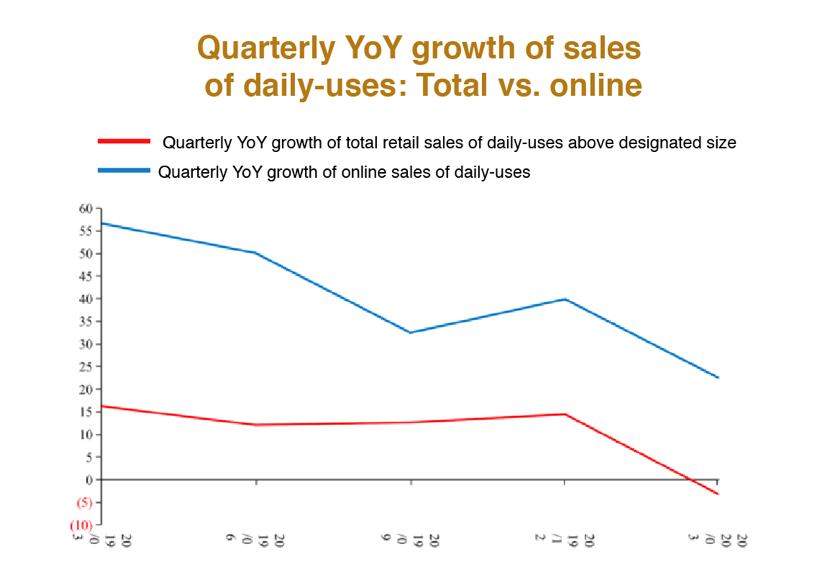

If we only look at the category of daily-uses, their online and offline consumption have fallen almost the same.

Figure 8: Impact of the pandemic on sales of daily-uses

Sources: Wind, ECDataway, Essence Securities.

Notes:

(1) Daily-uses include household and personal cleaning products, detergents, sanitary pads, tissues and toilet paper, perfumes, makeups, skincare products, diapers, wigs, strollers and other personal care items.

(2) Data for total retail sales of daily-uses above designated size are from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, while that for online sales of daily-uses is from ECDataway. The two sets of data are measured with different statistical methods that cannot be unified.

An important question here is, if offline spending drops because people are disinclined to dine, travel or shop outdoors to avoid infections, why have online transactions of non-necessities experienced a similar plunge? That cannot be explained by infection risks or control measures, anyway.

People's behavior and decision have evolved through the following three levels under the shock of the coronavirus pandemic:

The first level is panic. In the face of an event featuring unknown transmission risks and unknown risks to health, people naturally have panic feelings and want to put themselves in a safe environment. People will not only reduce going out, but will also focus their online trading activities on daily necessities. The panic feelings will gradually fade as time passes and more information becomes available.

The second level is adaption. If the risk of infection is expected to exist for a long time, people will evaluate the infection risks of various trading behaviors, the potential benefits of such behaviors, and the availability and effectiveness of protective measures. Then they will gradually restore economic activities with large gains and small infection risks, thus dynamically adapting to the new living environment.

The third level is expectation adjustment, which is to assess the impact of the pandemic on personal long-term income prospects and short-term cash flow, and adjust their spending plans accordingly.

Based on observation of data and trading behaviors in the financial market, it can be found that a distinctive feature of the first level is that when people are faced with huge short-term uncertainties, they quickly place themselves in a safe environment, and become less capable of making rational decisions. But people's cognitive ability will gradually recover as their panic slowly disappears, and they will progressively relax unnecessary protective measures once taken due to panic. Consumer behavior will gradually return to normal spontaneously, such as online transactions that have no infection risk.

I think this adjustment process is not only applicable to consumer behavior, but also the behavior of government, financial investors and entrepreneurs.

For ordinary consumers, the abatement of panic has significantly restored many online consumer activities. For local governments, the excessively strict control policies in the early stage have gradually been relaxed, which can help restore the supply capacity of the economy. According to the monthly data, the recovery of industrial production in March is closely related to the lifting of supply restrictions. For stock investors, the adjustment mentioned above is very obvious. When the pandemic broke out, stock price fell sharply, but after one or two days the market returned to normal and began to rebound. It proved that the fall of the stock price on the first day was caused by irrational panic.

At the second level, when the pandemic situation has been put under control, people start to think about which transactions would incur extremely large risks and thus to avoid such transactions; which transaction risks are controllable, or at least can be significantly reduced through certain technical means. In this way people adjust their own behavior to adapt to an environment where the pandemic may exist for a long time and reappear repeatedly. In this environment, people will take protective measures, but these measures are differentiated even for offline activities. People would assess the risks and benefits of each transaction, take a balance between the two, and decide what additional measures can reduce the risks.

I think that it is impossible for people to completely reject trading behaviors that involve risks. For instance, people know that air travel has a very low possibility of accidents which bring life-threatening risks, but they still choose air travel because they believe that the convenience it brings outweighs the possible risks it may incur. Through this extreme case, I want to explain that although many offline activities have certain risks amid the pandemic, people will gradually develop differentiated control measures for different trading behaviors and evaluate costs and benefits separately. In this context, many offline transactions will gradually recover.

Not only do consumers make such assessments, the government also assesses what measures can better restore the economy without risking too much of a resurgence of the pandemic, and optimize such measures through trial and error. Entrepreneurs will follow similar behavioral patterns to make investment arrangements.

I think that China has been making such adjustments in the past month and a half, and it has worked well so far. Although there are some sporadic new cases in the provinces of Guangdong and Heilongjiang, the disease is being kept under control. In many regions, economic activities have gradually recovered to an active level.

To be fair, even if the economic activities fully normalize, it is difficult for them to return to the level of activeness before the pandemic as long as the risk of outbreak is not completely eliminated. However, our current situation is still far from the optimal state of coexisting with the virus, so we still need to making adjustments in that direction and we are doing so now.

III. Pay attention to industries, companies and individuals that have suffered badly; stabilize the stock of social capital

At the third level, people will assess the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on personal long-term income and short-term cash flow when they get out of the panic mode, and based on which, adjust their spending plans.

If long-term income is expected to decrease, it is necessary to reduce spending and postpone the consumption of many durable consumer goods. For example, if you want to buy a big house, you have to settle with a smaller one now.

In a general sense, for people with middle-to-high income, a certain level of financial assets and savings, and relatively good credit qualifications, if their long-term income stream is not affected, the impact on their short-term consumption behavior will also be relatively small, because they can support short-term expenses by using credit or financial assets and savings.

Will the coronavirus pandemic have a systematic impact on the long-term economy? No consensus has been reached yet. I personally think that for a three to ten-year cycle, the impact of the pandemic on long-term economic growth and income is negligible. Some industries will be more affected, and their formats and business models will be disrupted, but others will develop better in the post-pandemic era. From historical experience, the impact of pandemics on long-term economic aggregate is very limited. The average economic growth rate in the next three to ten years may even be slightly higher because the inherent momentum of the economy will drive its gradual recovery to the average level. Therefore, I think the impact of the pandemic on the consumption behavior of most middle- and high-income earners will not be great.

But for some other groups, their long-term income expectations may not change (this is a big possibility), but their incomes have dropped sharply in the short term; they do not have sufficient financial asset reserves, or even have certain financial liabilities, for example they may have children about to go to universities, or have installment loans; at the same time, it’s difficult for them to obtain low-cost credit. For this group of people, the pandemic can cause great social suffering in the short term; for the total economy, this group of people will be forced to reduce consumption expenditures under liquidity constraints, which will cause a secondary economic contraction, dragging down economic recovery.

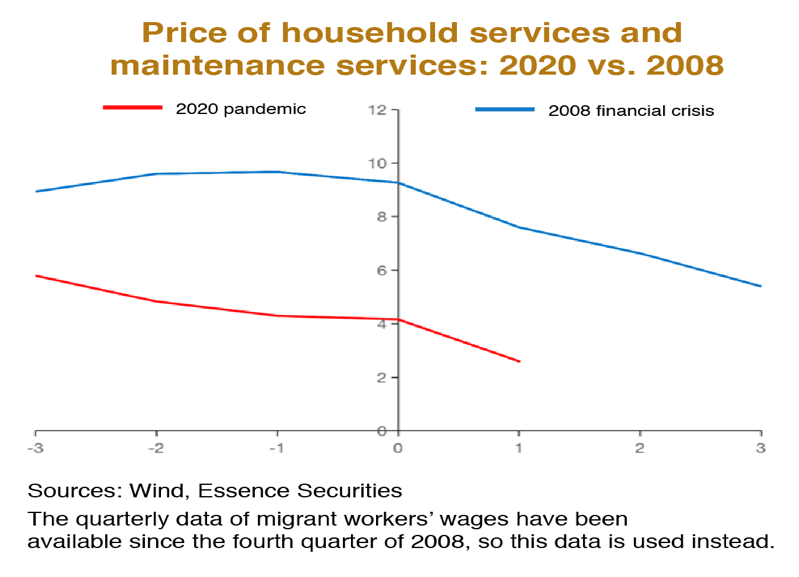

There is a sub-item in the general CPI called the price of household services and maintenance services. This indicator is worth paying attention to for the following two reasons: First, it has a stable long-term sequence, and is published monthly along with CPI. Second, it measures the price of services dominated by relatively low-end labor such as plumbers, nannies, and housekeeping workers. Although the change of this indicator does not strictly correspond to the price change of the low-end labor market, the direction and magnitude of the change are closely related to the wages of the low-end labor force.

Statistics show that the price of household services and maintenance services during the pandemic fell as much as that during the 2008 financial crisis. In other words, taking the price changes during the financial crisis as a reference, in the field of household services and maintenance services, the relative decline in prices is five times that of the overall price level.

Figure 9: The impact of the financial crisis and the pandemic on the price of household services and maintenance services

In the context of the overall price decline being much lower than that during the 2008 financial crisis, the price decline in this area is close to that in 2008. This raises several questions:

First, in the low-end labor market, people's willingness to work dropped significantly. For many migrant workers, going out to work may cause infection which means severe, even life-threatening health consequences, and perhaps high treatment costs and other opportunity costs. Therefore, the willingness to go out to work has declined, not entirely because of the lockdown policy, but also out of concerns about risks from migrant workers themselves.

Despite suppressed supply of labor, the price of labor in this area is still going down, which shows that the demand for labor is seeing an even sharper decline. In recent years, the number of new jobs in China's secondary industry (mainly the industrial and construction sectors) has been consistently below zero. Generally speaking, the labor force continues to leave this market. But the economy as a whole is still creating a lot of jobs every year, and the majority of these jobs are from the services sector. In 2018, the labor force absorbed by the service sector accounted for 47% of the total employment in the society, reaching 350 million.

In the services sector, the healthcare industry and some parts of the IT industry may have been positively affected by the pandemic. What's more, its impact on many sub-sectors of the financial industry is very limited. However, some relatively low-end sectors with particularly high employment density where the labor force features low level of education and wages have been severely affected by the pandemic, such as offline storage, retail, catering, tourism, and hotels. It can be said that the coronavirus pandemic has hit the total demand hard, but its shock to the services sector is more serious than to commodities, and the industrial and construction sectors. This can explain the fact seen at the aggregate level that the low-end labor market is relatively more negatively impacted.

A more serious problem is that if the pandemic mainly affects high-income people, their consumption expenditure will be relatively less affected; but if the impact is mainly on the low-end labor force, due to the pressure of cash flow, the shock will soon be converted into significant decline in consumer activities, which will in turn cause secondary damage to the economy.

Can we provide this group with some income supports to boost spending?

We need to figure several things out first:

One, is this the most effective stimulus measure? I don’t think so. People receiving the relief may spend 90% of it, which may boost demand, but the propensity to consume will not surpass 1 (i.e., they will not spend more than what they get from the government). However, if the government uses that money to invest in infrastructure with banks providing additional loans, the demand thusly created may exceeds the initial amount of money input.

Two, where does the money come from? Obviously, it comes from the issuance of government bonds. But at the end of the day, the costs of government bonds will fall on the shoulders of future taxpayers, and in the worst case, they will have to be absorbed through inflation. This is basically a matter of income transfers among population groups or even across generations, and even if it does not affect the consumption propensity of these taxpayers for now, it will compromise social fairness.

In other words, we will have to increase the burdens on future taxpayers to support the issuance of government bonds right now, so that low-income people receive necessary transfer payments to sustain their lives, and the aggregate demand do not further contract. As far as I can see, it may not be the most effective way to boost demands, but it embodies humanism and highlights the importance to reach out to the vulnerable or hard-hit groups amid a crisis.

The same is true with sectors and businesses that have taken the brunt of the pandemic’s shocks—the government has the responsibility to offer them help even if it cannot stimulate demand maximumly. Besides, many of small- and medium-sized enterprises in these sectors possess huge amounts of social capital, including customer networks, management skills and brands. Transfer payments will help secure these social capital, stabilize employment, and boost economic recovery after the virus is brought under control.

In this sense, this support measure will help maintain effective social capital without distorting resource allocation, and it is very flexible and controllable. In these areas, it is more efficient than expanding infrastructure investment in boosting demands.

IV. Conclusion

This article features three core observations:

First, during the pandemic, total economic output and the general price level have experienced highly diverging patterns: the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on China's output is two to four times that of the financial tsunami in 2008, while the influence on the price level is only 20% of that twelve years ago.

The policy implication here is that disruptions in aggregate supply constitute an important component in economic fluctuations amid the pandemic—the supply side has taken a blow only slightly smaller than that to the aggregate demand. Before the lockdown on aggregate supply is lifted, stimulating aggregate demand alone may not achieve the desired results, if not inducing inflations; on the contrary, if we gradually unfreeze the supply while keeping the virus under control, the economy will pick up as a matter of course. That means policymakers should not rely too much on aggregate demand management; instead, fluctuations in both aggregate demands and supplies as well as the gap in between and how it changes over time deserve equal considerations.

Second, during the outbreak, online spending on non-necessities such as garments and daily-uses have plunged together with offline spending, which have shed some light on the complexity of consumer behaviors under the shocks.

In general, consumers, businesses and the government have all experienced or are all experiencing the transition from panic to adaptation, and then to the adjustment of expectations. This transition has driven the changes in their behaviors and the recent fluctuations of macroeconomic figures.

To be honest, even if the economy is normalized, it can hardly resume the vigor before the pandemic until related risks are eradicated. That said, we are still far from the best state to coexist with the virus, and that is where we are working gradually to reach.

Third, the price of household services and maintenance services in the CPI in the first quarter this year has decreased by as much as in the 2008 financial crisis. In other words, benchmarked against twelve years ago, the relative decline in the price for these services has been five times as much as that in the general price level.

This shows the extremely huge blow the pandemic has dealt to the demands for low-end labor (and related sectors and SMEs).

More generally, some of the sectors and businesses, especially SMEs and low-income groups have suffered significantly larger shocks, and transfer payments and other sorts of reliefs are necessary to support them. While this cannot boost short-term demands to the highest degree, it is the responsibilities of the society to provide aid for vulnerable and hard-hit groups.

Meanwhile, these sectors and businesses possess large amounts of social capital, including customer networks, management skills and brands. Transfer payments to them will help secure these effective social capital, stabilize employment, and boost economic recovery after the pandemic.

Compared with infrastructure investments, transfer payments can help maintain and increase social capital stock without distorting resource allocation, and it is very flexible and controllable.